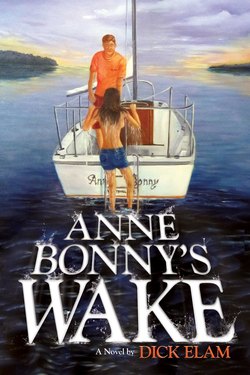

Читать книгу Anne Bonny's Wake - Dick Elam - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

Scree-e-e-eech.

The shrill pierced quiet Bear Creek. I knew the noise, but the Bear looked alarmed and stayed bent over his shotgun.

“My teakettle’s boiling,” I said.

The Bear relaxed his grip on the shotgun, stood up straight.

What else sounds like a teakettle? A woman’s scream? A police whistle? Whatever the Bear thought he heard, he’s jumpy. Don’t rush anything.

“I’d better get the kettle.” I turned toward the hatch.

A second screech accompanied the teakettle shrill.

“What-in-the-hell? Get the teakettle! Never mind. I’ll get the damn teakettle!” Her voice cursed me: “Damn you, you said I could sleep late.”

From my cockpit vantage, I saw her bang open the head door. The brunette swimmer had turned herself into a plump hag. She waddled into the cabin. The hag grabbed the teakettle and set the steaming pot on the unused burner. The woman also reached into the utensil drawer. I saw her take out a second knife. Where had she concealed the first knife?

The Bear leaned forward. I don’t think he could see down into the cabin. But he was trying.

“You wanna keep this stinking fire going?” she rasped loudly.

I didn’t answer—missed my cue.

Her costume matched her shrewish voice: She wore my long-sleeved sweatshirt. The sweatshirt flowed over a stomach that swelled over a pair of my Bermuda shorts. Front pockets bulged, suggesting fat thighs, and the pants expanded to maximum beam width. She had encased her feet with tubular wool socks, the pair I wear in my foul-weather boots. The top of the right sock slouched over her ankle, while the other sock rose to just below her knee.

“Dammit! What rotten time did you get out of bed? Mix me one of those damn instant coffees while I use the head.” She clomped toward the bathroom. Her hair expanded like a porcupine, boxing the compass with an assortment of gray, black, and white strands.

The Bear had drifted where he might better see her performance. To keep his fishing boat close, he grasped the backstay, the wire strung from the mast top to the stern. That cable controlled the mast’s forward bend. The Bear’s muscles looked strong enough, his hands calloused enough, to climb, hand-over-hand, up that stainless steel cable, over our cockpit, to the top of the mast.

I turned aft, faced him. He held the backstay in his left hand, but in his right hand he grasped the shotgun.

His eyes studied me. Was he trying to match my face lines with furrows in the crone’s face? Did I look older than my forty-six years? My sideburns show gray, but my hair remains red, a gift from my English ancestry. I didn’t inherit the strong English nose or the angular cheekbones. My round face and pug nose endowed me with what my wife, Annie, used to call the “Andy Hardy look.”

The voice shrilled again from the cabin.

“Don’t buy any damn fish. If you buy any of his damn fish, you gotta clean and cook ’em. Hear me? No fish!”

I yelled back: “I hear you. I hear you. He isn’t selling fish. And don’t put any toilet paper in the head. I’m not going to clean that toilet out for you again.” That admonition came easily, even though I hadn’t spoken that advice for over four years.

Then I turned and shared my troubles with the Bear.

“She won’t learn that you don’t put anything in the toilet that you haven’t digested.”

He nodded, an understanding exchange.

I continued with a disgusting tone: “She wanted to spend the night at Belhaven. Likes the oyster fritters there. Should never have anchored her in a quiet place like this.”

The Bear began to look bored.

“Sorry. Not your problem. How can I help you?”

The Bear wrinkled his face into a look that suggested condolence.

“Hmmpfh. Don’t suppose you saw any boats come up Bear Creek last night, or any people around much earlier this morning, did you? Would have been a small motorboat with a man and a woman aboard.”

“No boats last night or this morning. And I woke up at dawn. Always do. Like the time to myself.” Told him no lies.

The Bear nodded sympathetically when I said “time to myself.” He pushed away.

“Thanks. And excuse me to your woman.” He half-smiled. I frowned, trying to stay in my new character.

The Bear shifted from neutral. At slow speed, he drove by the starboard side. The Bear looked in the cabin window, then shook his head.

He motored up Bear Creek. When he turned out of my sight, I looked down into the cabin. She leaned near a porthole, watched the Bear motor out of her sight.

My commonsense brain told me, Professor Barstow, you are acting in a drama for which you didn’t audition. The Bear’s shotgun, plus the butcher knife the woman had extracted from the galley, suggested serious props. The Bear had said he was hunting for a woman who rode in a motorboat with a man. There’s another character in this nautical drama—a man who might carry a spear, pistol, or shotgun.

I wondered if I should arm myself.

I’d read that sailors who cruised the Caribbean differed on whether to arm against boarders. Unarmed cruising sailors feared that drug pirates would seize their boat, deliver dope; then the drug traffickers would scuttle the craft. On the other hand, armed cruising sailors might be wiser not to brandish a gun and cause the pirates, with automatic rifles, to shoot to kill.

I recalled countermeasures from yachting magazine articles. One writer recommended, “defend yourself with a flare gun.” At close range, as boarders climb over the side, you fire a hot flare into an attacker’s chest.

Another writer suggested to “spray a fire extinguisher in their faces.”

Took inventory:

I kept a flare gun below in the bulkhead cabinet above the navigation station.

Mentally counted three fire extinguishers: one located above the stove, and a second mounted at the navigator’s feet. Up here in the cockpit, I could open the starboard cockpit compartment and find another fire extinguisher.

When we had owned the Anne Bonny, I’d bought extra fire extinguishers, but not to repel boarders. I’d worried about a gasoline engine fire. That’s why I always ran the exhaust fan—the bilge blower—usually five minutes before I started the gasoline engine. I had considered exchanging the Atomic 4 gasoline engine for a diesel engine to reduce the fire hazard. Discarded that idea when I priced a diesel motor. Just made sure the bilge blower exhausted any gasoline fumes.

Two winch handles were holstered in the cockpit. Those twelve-inch-long bludgeons, cast from bronze, would crack a rib or crush a skull. Hoped I didn’t need to marshal the martial arts that Bill Havins had taught me a decade ago.

I pulled one winch handle and pocketed the heavy handle in my cargo pants.

The Bear could only motor so far up Bear Creek. When the creek shallowed, I expected he would return.

The hatch cover squeaked, and the woman stood in the hatch opening. She held two cups of coffee. Steam rose from the coffee cups and created a witch’s cauldron allusion. Her makeup fit the part of a crone.

Hell of a makeup job, I thought. The young woman had drawn facial lines with the soft lead pencil from the navigation equipment drawer. The lines extended across her forehead. She’d also marked heavy lines from her nose to below her mouth and drawn small vertical lines on the corner of her lips.

Her hair stuck together. She had combed streaks of white and gray goo through her black hair. I could smell the acrid resin.

“What did you put on your hair?”

“Stuff out of the cans I found. White latex paint came from a bottom drawer, where I also found the fiberglass putty.”

“You didn’t put the hardener in the fiberglass, did you? You didn’t add the catalyst from the small plastic tube, did you?”

“No. Would it have made me more beautiful?”

“Don’t know how you could improve, but your hair would become a ‘permanent’ permanent wave.”

She handed me my cup of instant coffee.

“He will come back by here,” I warned.

She nodded, sat next to the cabin bulkhead, her back to the sun. You couldn’t see much of her unless you looked across my shoulder, and then you would look into the rising sun.

I waited for her to speak. The coffee wasn’t boiling, but warmed the roof of my mouth. Wished for honey to sweeten the taste. Maybe she would alleviate the synthetic coffee taste if she said something.

She listened. Her eyes swept the creek banks. She looked past me and over Anne Bonny’s port quarter. Then she looked back toward the channel marker and the river buoy. Finally, she cut her eyes over my shoulder.

She spoke loudly, in a whining, nasal rasp that matched her hag costume.

“Damn, lousy coffee. Don’t expect me to cook breakfast. Get it yourself.”

She warned me we were still onstage.

“Uh-huh.”

That wasn’t much of a stage line, but I hadn’t developed my method to play opposite Virginia Woolf. A previous woman, who’d served a kiss with my morning coffee, had spoiled me.

Resisted the urge to look over my shoulder. Tried to act the dutiful husband contemplating, Why did I marry you? I answered myself: To inherit your father’s business and own the sailboat that I always wanted. Or because I remembered you as a bare-breasted maiden, rising like a goddess from the sea.

“Don’t hear his motor?” she whispered. “Do you?”

I listened. Turned so I could hear with my right ear. My left ear misses certain tones. Flying a single-engine, noisy Cessna 172, shooting ducks without earplugs hadn’t helped my hearing. The Navy medic who discovered my hearing loss said he couldn’t qualify me for submariner duty. Hah—a small penalty for taking sky with your water.

The woman whispered: “He’s ashore. Went ashore up the creek and walked back where he could see your boat. He’s standing in the trees, watching me from over your shoulder. Sit tight. We’ll know in a few minutes.”

I didn’t turn and look, but I touched the winch handle in my pants. My fingers squeezed the cold brass. With my other hand, I drank weak coffee.

Then I heard a motor starting. And sounding louder. My eyes focused on the returning motorboat.

The Bear, again, set a course toward the Anne Bonny.