Читать книгу Anne Bonny's Wake - Dick Elam - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 7

Bill’s voice rose, audible in the cockpit.

“Calling Bon Ami. Good-looking, Bon Ami. Got my binoculars on you.”

I wished that Bill Havins had quit talking after he radioed my dock berth number. I could see the picture window of his office. Knew he watched from his wheelchair, his binoculars trained on—what else?—the woman.

“See you found new help. My compliments to your new crew. Over and out.” Bill signed off. And, as usual, Bill Havins had sounded off.

The concerned look on Maggie Moore’s face, a frown I had not seen since the Bear motored away, told me she knew most skippers keep their radios turned on in case someone called the distress call, “Mayday.” Gathered Maggie didn’t want her presence broadcast to every boat radio on the Neuse and Pamlico.

Or Maggie might have looked concerned because we faced the Oriental highway bridge, spinnaker flying.

I didn’t bother to sign off. Hung up the microphone. Jumped into the cockpit and un-cleated the spinnaker halyard. Handed Maggie the halyard. Un-cleated the spinnaker guy and held the rope in my hand. Jumped onto the deck. Freed the spinnaker pole. Jumped back into the cockpit. Grabbed the leeward corner of the spinnaker and pulled the spinnaker toward the cockpit.

“Ease the spinnaker halyard.”

Maggie nodded, freed the halyard. That line went up, and the sail came down. I dumped the orange nylon through the hatch, down into the cabin.

“Follow the markers into the harbor,” I commanded.

Maggie steered into the Oriental channel. She knew her buoyage system. Without asking, she kept “red, right, returning.”

I switched on the bilge blower. We now sailed under mainsail alone, ready to start the motor, if needed.

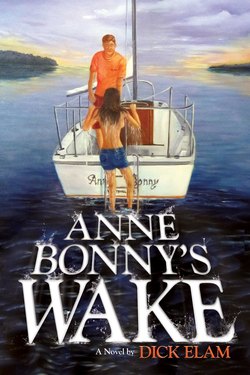

The Anne Bonny turned deeper into the quiet waters of Oriental harbor. The city dock lay straight ahead, butted to a concrete bulkhead that shored Oriental’s downtown Main Street. On the left, an eighty-foot fishing boat lay against the cannery dock.

We sailed by a black hull I recognized as Peril, a C&C class 32 that I used to race against. A physician owned the sloop. Something different. She used to be yellow—the yellow Peril. What should the name of the black boat now read? “Plague”?

I expected Bill Havins still watched from his Dockside chandlery. Probably adjusted his binoculars to examine the woman in the blue turban and the blossoming orange T-shirt.

The Anne Bonny drifted into quiet waters. The bilge blower hummed and I smelled no fumes, so I started the motor and Maggie turned back into the wind.

I lowered the mainsail, furled the sail, secured it by tying four cloth ties around the sail gathered on the boom. Tied fenders amidships to avoid bumps on either beam, and took the helm. If the boat knocked down the pier, I wanted the wreck charged to me, not the crew. I shifted the propeller to neutral. We coasted, losing momentum. I don’t rely on reversing the propeller to stop a 10,500-pound sailboat. A sailboat is a she because a boat is difficult to back down.

Jimmy signaled directions to our docking space near Main Street. I poked the sloop’s nose between the pilings. Maggie threw Jimmy a line from the forward deck, and I looped a stern line over the windward post. We both pulled tight, and Anne Bonny rested in her stall. Proud I didn’t need to reverse the propeller to stop her.

“Hey, Hersh. Welcome back.”

Jimmy spoke to me, but his eyes flickered between Maggie, then me.

The Oriental High School senior performed Bill’s weekend legwork, pumped gas, or tied your line. He shook my hand and palmed, clandestinely, the key to the motel room. Jimmy would graduate this year, but he already knew why old men with young female crews rented motel rooms.

“Gotta go. See you later,” Jimmy said.

“What’s the hurry, Jimmy?”

“Got diesel to pump and photographs in the hypo.”

As I watched Jimmy jog to the diesel pump, I saw Bill Havins roll his wheelchair out on the Chandlery porch, down the inclined ramp onto his concrete walkway.

I waved. Bill waved back, then returned his hands to spin the wheels and aim the wheelchair. His eyes centered on my newfound shipmate.

Maggie leaned against the mast and watched Bill approach. She bent one knee and propped the sole of a naked foot against the mast. Her fashion model’s pose stretched the Anne Bonny letters on her T-shirt.

Bill rolled slowly, looking Maggie over like a bird dog on point.

“Ahoy, Bon Ami.”

“Hi, Bill. Come down to make sure I didn’t wreck your flimsy dock?”

“What says you, Hersh? That dock would sheer that old boat off right at your orange waterline stripe.” Bill looked Maggie over while he waited for an introduction.

“Maggie Moore, meet Bill Havins.”

She smiled, nodded. He smiled back.

“Glad to meet you, Maggie. See you at dinner?”

Bill presumed too much, and I intended to tell him so when I cornered him in the Chandlery. I spoke quickly before Maggie could answer. “I’ll see you as soon as I get cleaned up and the boat washed down. Min going to join us?”

“Sister Min wouldn’t miss a chance to scold her little brother Hersh. I’ve already called her. She’s coming over for cocktails. Where you want to eat?”

“Same as always, the Oriental Restaurant. Need some good seafood.”

“I’ll have Andy give us a table overlooking the sunset. See you. Glad to meet you, Maggie.” Bill spun the wheelchair around. Jimmy trotted from the diesel pump and pushed Bill on the concrete walk, up the ramp onto the porch outside the Chandlery.

Maggie adjusted a fender and then eased into the cockpit. Her raised eyebrows compelled an invitation and explanation.

“I hope you will join us for dinner. You’ll like Min,” I said.

“Thank you. You’re kind to include me. But I feel like the stranger crashing a family supper. I’ll just explore Oriental by foot. Then stay aboard. Besides, I don’t have dinner clothes.”

“No problem. Bill will help me solve the clothes problem. The motel room is for you. Here’s the key to room six. Got a shower, and you can shampoo your hair. Some shampoo in the head. Take that.”

“That’s nice, but why don’t you take the room, and I’ll sleep aboard.”

“Maggie, when you get to know Bill’s wife, Min Havins, you’ll know why I wouldn’t dare, even if I wanted. I’ll shower in the men’s dressing room.”

She thanked me again. Maggie had parlayed a ride to Oriental. Invited herself to sail to Wrightsville Beach. Yet she acted surprised at my generosity. Or was a ride all she wanted, and now, like Greta Garbo, she “vanted to be alone”? Or, she flinched because she didn’t bring her dinner clothes? I planned to solve that problem.

“I’ll help you unrig, and then I’ll go to the room,” she said. “I thank you, but I can’t pay you now for the room. I’ve got a few coins in my jeans, but no currency. I’ll reimburse you when we get to Wrightsville Beach.”

“No problem. We’ll settle then.” I wondered if she would really pay me, and how, but we had moved to one understanding: she wasn’t asking to be a kept woman.

Unrigging a sailboat takes a while, even when your jib rolls up like a window shade. We spread the spinnaker on the grass and repacked it in its bag. While I hooked up shore power, Maggie took the bagged sail below. She pumped the bilge, emptied the trash, and, at my insistence, sat in the cockpit while I coiled lines and stowed winch handles.

I went below and entered log notes:

Oriental Dockside. 2:47 . . . Need: refuel, buy stretch cord, etc. for MM

Then I gathered two beers, a can of Vienna sausages, cheese slices, and a box of saltine crackers and carried the food, plus paper towels, into the cockpit. Maggie thanked me for the beer, ate some cheese atop crackers, but she declined my other hors d’oeuvre.

The early afternoon May sun shone warm, but not hot. The wind blew away the cannery smell across the Oriental harbor.

Oriental took its name, so the natives say, from a wrecked ship nameplate that washed ashore sometime in the 1700s. Now some two hundred sailing yachts berth in Oriental. Most of the racing yachts moor at Pierce Creek Marina. Transient yachts drop anchor in the harbor or moor at Bill Havins’s Dockside. Only a few skippers use the city dock that shallows when a north wind blows.

In our peaceful anchorage, l determined to interrogate Miss Maggie Adelaide Moore.

First I complimented Maggie on her sailing. Where had she learned so well?

From her father: Ashley Jerome Moore, who treated his timid daughter like a shipmate. Maggie sniffed after she named her father. Remembering must have struck a nerve, but her face brightened.

Where did her father sail?

Wherever the company sent him.

What was her father’s business?

Accounting.

Was Dad a certified public accountant?

No.

For what company did Dad work?

Different oil companies that sell gasoline to service stations.

Where did they live?

All over the South.

You show me a service station, and I’ll show you an oil wholesaler. Ashley Jerome Moore’s job was difficult to categorize by region.

Maggie answered cheerfully, apparently animated by my interest in her racing training. She didn’t provide enough information to categorize the Moore family by sailboat class. I shop all the time for another sailboat. You tell me what sailboat you own, and I can estimate your boat investment. Maggie said they’d once owned a family sailboat, but now she crewed for other people.

Before I could ask what kind of boat they had owned, Maggie added details about her family: Her dad had died when she was fourteen. (She sniffed.) Her mother lived on annuities. Mom lived in Hilton Head, but traveled extensively, renting out her condominium and visiting relatives.

Tracing Maggie Adelaide Moore would be an easy task for the Havinses. I knew Min would snoop in her customary, bosom-buddy, prying way. And I had gathered some data Bill could trace through his Washington, DC, connections.

I refrained from follow-up questions. Deferred to the mental adjustment that follows a sailboat race—a moment of recuperation. Sensed that Maggie understood the social graces of the after-race snack: easy talk, compliments to the crew, a few complaints—and only directed against yourself. Always followed by a restorative spirit, a mental refurbishing, and another drink.

“How about another beer?” Maggie asked.

When I nodded, she danced into the cabin. She passed a beer up through the hatch, opened and raised her beer in salute. I responded.

“Hersh, I hope you won’t mind me noticing all the books you keep in the shelf below. I would like to read the Russian’s book about opening chess moves. Otherwise, your books are tomes about justice, police, and testimony, except I detected a slim pamphlet with Herschel Barstow’s name on the cover, and pages turned down.”

“Guilty. That’s my first textbook. I’m working on a revised edition.”

Maggie beamed. “I noticed the title: Just the Facts. Sounds like Sergeant Friday on the TV show Dragnet.”

“Guilty, again. It’s a manual intended to teach future cops how to write short sentences. Write active verbs. Avoid using the pronoun ‘I.’ I hear the students call my writing course ‘Police Blotter 101.’ But I teach them how they ‘write it down’ at the cop shops.”

Maggie saluted me. “Yes, sir. Know the drill. I told you I worked at the Wilmington police station once. My uncle Glenn got me the temp job. He’s been a policeman all his life. Professor, did you go to a criminal justice college or work in law enforcement?”

“Neither.” I smiled back, but I dropped my eyes because I wasn’t ready to expound my criminal justice teaching credentials, and I didn’t want her digging into my previous government service.

“Because I went back to college for an advanced degree and learned about computers, I wrote a dissertation about collecting crime, espionage data and—”

“Aha.” She raised her index finger to accompany her amused smile. “And do you have your own code number, like 007?”

“No way. But who will ever forget that number? I read the first of the series. Remember the year was 1953. Borrowed that first James Bond book from a dorm friend. Should have studied for my Spanish final exam, but didn’t finish reading the book until the morning of the exam.”

“And how did you do on the Spanish exam?” Maggie asked, a twinkle in her eyes.

“Okay on vocabulary. Terrible on the grammar part. Damn near failed the course, but got a D,” I answered. Her eyes laughed back at me.

Those wrinkles in her eye corners may have answered my question, how old are you, Maggie? Maybe just sun wrinkles that came with her bronzed body. I thought she might be, say, thirty-five. But with her good looks, she could be fifteen years younger than me.

“Hersh, you’re not the only Ian Fleming indulger. I’ve read all his 007 books. Cried when Fleming died in 1964.”

I started to ask, “In college in the mid-’60s?” but squashed that impulse. If I asked her at what age she went to college, she would ask me for my age. Hell, she had already heard enough details to figure my age was in the mid-forties. The devil with her. She could calculate anything she wanted.

Silence boxed our conversation. I should have remembered the conversation rule practiced at officer’s mess: don’t discuss religion, politics, or age in the ship’s wardroom. Decided against that prohibition. I wanted to know more about her religion, her politics, and why she clouded details from her past.

“I didn’t mean to pry.” Her tone sounded apologetic. “I’ve read a lot about how writers work. I majored in English lit in college. I learned that you writers read and collect books. And, Hersh, you have accumulated a similar book investment down in the cabin. Just noticed a lot of crime titles.”

That was fair. She’d told me something about her scholarly interest. Quid pro quo. I owed her something about my scholarship.

“I teach criminal justice students how to write arrest reports, how to testify in court. I’m not an attorney, but at the advanced level I teach legal theories. I didn’t bring a copy aboard, but my second book is entitled Or, Give Me Justice.”

“What’s that all about?”

“It’s ‘all about’ supporting the law, because without justice, we can’t enjoy liberty.”

I noticed Maggie’s eyes began to glaze over. Decided not to tell her about my dissertation about drug enforcement cases that I’d turned into my first book.

“Where do you profess?” Maggie asked.

“I teach at Henry Campbell Black College. Small, special curriculum college located outside Alexandria.”

“Oh, yes. I know about Campbell Black. I now live about twenty miles away from the campus. Your college was named for a judge, wasn’t it?”

Her reply surprised me. Although criminal justice scholars knew Henry Campbell Black’s opinions and scholarly fame, not many people knew about the college endowed by his mother’s family. Should I ask for her street address? But Maggie beat me to the questions:

“Are you a doctor—a PhD?”

“Yes.”

“And are you a tenured professor at Campbell Black?”

“Well, yes, I am.”

“All right, Doc. I’m impressed. I’m also glad you’re not reading all those crime books because you’re writing paperback mystery potboilers. Where did you receive your PhD?”

“From Georgetown,” I answered with some delight—until I realized how much information she had wrung from me with a passing reference to literature. I had intended to conduct this interrogation.

Asked myself: Dr. Barstow, who’s giving this quiz?