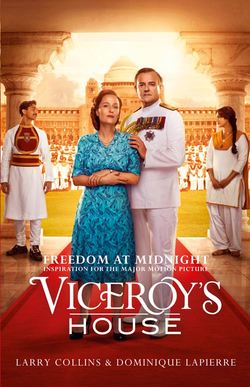

Читать книгу Freedom at Midnight: Inspiration for the major motion picture Viceroy’s House - Dominique Lapierre, Larry Collins - Страница 12

THREE ‘Leave India to God’

ОглавлениеLondon, January 1947

‘Look,’ said Louis Mountbatten, ‘a terrible thing has happened.’

Two men were alone in the intimacy of a Buckingham Palace sitting-room. At times like this, there was never any formality between them. They sat side by side like a couple of old school friends chatting as they sipped their tea. Today, however, a special nuance enlivened Mountbatten’s conversational tone. His cousin King George VI represented his court of last appeal, the last faint hope that he might somehow avoid the stigma of becoming the man to cut Britain’s ties with India. The King was after all Emperor of India and entitled to the final word on his appointment as Viceroy. It was not to be the word the young admiral wished to hear.

‘I know,’ replied the King with his shy smile, ‘the Prime Minister’s already been to see me and I’ve agreed.’

‘You’ve agreed?’ asked Mountbatten. ‘Have you really thought it over?’

‘Oh, yes,’ replied the King quite cheerfully. ‘I’ve thought it over carefully.’

‘Look,’ said Mountbatten. ‘This is very dangerous. Nobody can foresee any way of finding an agreement out there. It’s almost impossible to find one. I’m your cousin. If I go out there and make the most deplorable mess, it will reflect very badly on you.’

‘Ah,’ said the sovereign, ‘but think how well it will reflect on the monarchy if you succeed.’

‘Well,’ sighed Mountbatten, sinking back into his chair, ‘that’s very optimistic of you.’

He could never sit there in that little salon without remembering another figure who used to sit in the chair across from his, another cousin, his closest friend, who had stood beside him on his wedding day at St Margaret’s, Westminster, the man who should have been King, David, Prince of Wales. From early boyhood, they had been close. When in 1936, as Edward VIII, David had abdicated the throne for which he had been trained because he was not prepared to rule without the woman he loved, ‘Dickie’ Mountbatten had haunted the corridors of his palace, the King’s constant solace and companion.

How ironic, Mountbatten thought. It was as David’s ADC that he had first set foot on the land he was now to liberate. It was 17 November 1921. India, the young Mountbatten had noted in his diary that night, ‘is the country one had always heard about, dreamt about, read about.’ Nothing on that extraordinary royal tour would disappoint his youthful expectations. The Raj was at its zenith then, and no attention was too lavish, no occasion too grand for the heir to the imperial throne, the Shahzada Sahib, and his party. They travelled in the white and gold viceregal train, their journey a round of parades, polo games, tiger hunts, moonlit rides on elephants, banquets and receptions of unsurpassed elegance proffered by the crown’s staunchest allies, the Indian princes. Leaving, Mountbatten thought, ‘India is the most marvellous country and the Viceroy has the most marvellous job in the world.’

Now, with the confirming nod of another cousin, that ‘marvellous job’ was his.

A brief silence filled the Buckingham Palace sitting-room. With it, Louis Mountbatten sensed a shift in his cousin’s mood.

‘It’s too bad,’ the King said, a melancholy undertone to his voice, ‘I always wanted to come out to see you in Southeast Asia when you were fighting there, and then go to India, but Winston stopped it. I’d hoped at least to go out to India after the war. Now I’m afraid I shan’t be able to.’

t’s sad,’ he continued, ‘I’ve been crowned Emperor of India without ever having gone to India and now I shall lose the title from here in this palace in London.’

Indeed, George VI would die without ever setting foot on that fabulous land. There would never be a tiger hunt for him, no parade of elephants jangling past in silver and gold, no line of bejewelled maharajas bowing to his person.

His had been the crumbs of the Victorian table, a reign unexpected in its origins, conceived and matured in the shadows of war, now to be accomplished in the austerity of a post-war, Socialist England. On the May morning in 1937 when the Archbishop of Canterbury had pronounced Prince Albert, Duke of York, George the Sixth, by the Grace of God, King of Great Britain, Ireland and the British Dominions beyond the seas, Defender of the Faith, Emperor of India, 16 million of the 52 million square miles of land surface of the globe had been linked by one tie or another to his crown.

The central historic achievement of George VI’s reign would be the melancholy task foretold by the presence of his cousin in his sitting-room. He would be remembered by history as the monarch who had reigned over the dismemberment of the British Empire. Crowned King Emperor of an Empire that exceeded the most extravagant designs of Rome, Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, the Caliphs or Napoleon, he would die the sovereign of an island kingdom on its way to becoming just another European nation.

‘I know I’ve got to take the “I” out of GRI. I’ve got to give up being King Emperor,’ the monarch noted, ‘but I would be profoundly saddened if all the links with India were severed.’

George VI knew perfectly well that the great imperial dream had faded. But if it had to disappear, how sad it would be if some of its achievements and glories could not survive it, if what it had represented could not find an expression in some new form more compatible with a modern age.

‘It would be a pity,’ he observed, ‘if an independent India were to turn its back on the Commonwealth.’

The Commonwealth could indeed provide a framework in which George VI’s hopes might be realized. It could become a multi-racial assembly of independent nations with Britain, prima inter pares, at its core. Bound by common traditions, a common past, common symbolic ties to his crown, the Commonwealth could exercise great influence in world affairs. Britain, at the hub of such a body, would still speak in the councils of the world with an echo of that imperial voice that had once been hers. London might still be London; cultural, spiritual, financial and mercantile centre for much of the world. The imperial substance would have disappeared, but a shadow would remain to differentiate George VI’s island kingdom from those other nations across the English Channel.

If that ideal was to be realized, it was essential India remain within the Commonwealth. If India refused to join, the Afro-Asian nations which in their turn would accede to independence in the years to come would almost certainly follow her example. That would condemn the Commonwealth to become just a grouping of the Empire’s white dominions.

Influenced by a long anti-imperial tradition however, George VI’s Prime Minister and the Labour Party did not share the King’s inspiration. Attlee had not even told Mountbatten he was to make an effort to keep India in the Commonwealth.

George VI, as a constitutional monarch, could do virtually nothing to further his hopes. His cousin, however, could and Louis Mountbatten ardently shared the King’s aspirations. No member of the royal family had travelled as extensively in the old Empire as he had. His intellect had understood and accepted its imminent demise; his heart ached at the thought.

Sitting there in the Buckingham Palace sitting-room, Victoria’s two great-grandsons reached a private decision. Louis Mountbatten would become the agent of their common aspiration for the Commonwealth’s future.

In a few days, Mountbatten would insist that Attlee include in his terms of reference a specific injunction to maintain an independent India, united or divided, inside the Commonwealth if at all possible. In the weeks ahead, there could be no task to which India’s new Viceroy would devote more thought, more persuasiveness, more cunning than that of maintaining a link between India and his cousin’s crown.

In a sense, no one might seem more naturally destined to occupy the majestic office of Viceroy of India than Louis Mountbatten. His first public gesture had occurred during his christening when, with a wave of his infant fist, he had knocked the spectacles from the bridge of his great-grandmother’s imperial nose.

His family’s lineage, with one passage through the female line, went back to the Emperor Charlemagne. He was, or had been, related by blood or marriage to Kaiser Wilhelm II, Tsar Nicholas II, Alfonso XIII of Spain, Ferdinand I of Rumania, Gustav VI of Sweden, Constantine I of Greece, Haakon VII of Norway and Alexander I of Yugoslavia. For Louis Mountbatten, the crises of Europe had been family problems.

Thrones, however, had been in increasingly short supply by the time Mountbatten was eighteen at the end of the First World War. The fourth child of Victoria’s favourite granddaughter, Princess Victoria of Hesse, and Prince Louis of Battenberg, her cousin, had had to savour the royal existence at second hand, playing out the summers of his youth in the palaces of his more favoured cousins. The memories of those idyllic summers remained deeply etched in his memory: tea parties on the lawns of Windsor Castle at which every guest might have worn a crown; cruises on the yacht of the Tsar; rides through the forests around Saint Petersburg with his haemophiliac cousin, the Tsarevitch, and the Tsarevitch’s sister, the Grand Duchess Marie, with whom he fell in love.

With that background, Mountbatten could have enjoyed a modest income, token service under the crown; the pleasant existence of a handsome embellishment to the ceremonials of a declining caste. He had chosen quite a different course, however, and he stood this winter morning at the pinnacle of a remarkable career.

Mountbatten had just become 43 when, in the autumn of 1943, Winston Churchill, searching for ‘a young and vigorous mind’, had appointed him Supreme Allied Commander Southeast Asia. The authority and responsibility that command placed on his youthful shoulders had only one counterpart, the Supreme Allied Command of Dwight Eisenhower. One hundred and twenty-eight million people across a vast sweep of Asia fell under his charge. It was a command which at the time it was formed, he would later recall, had had ‘no victories and no priorities, only terrible morale, a terrible climate, a terrible foe and terrible defeats’.

Many of his subordinates were twenty years and three or four ranks his senior. Some tended to look on him as a playboy who used his royal connection to slip out of his dinner jacket into a naval uniform and temporarily abandon the dance floor of the Café de Paris for the battlefield.

He restored his men’s morale with personal tours to the front; asserted his authority over his generals by forcing them to fight through Burma’s terrible monsoon rains; cajoled, bullied and charmed every ounce of supplies he could get from his superiors in London and Washington.

By 1945, his once disorganized and demoralized command had won the greatest land victory ever wrought over a Japanese Army. Only the dropping of the atomic bomb prevented him from carrying out his grand design, Operation Zipper’, the landing of 250,000 men from ports 2000 miles away on the Malay Peninsula, an amphibious operation surpassed in size only by the Normandy landing.

As a boy, Mountbatten had chosen a naval officer’s career to emulate his father who had left his native Germany at fourteen and risen to the post of First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy. Mountbatten had barely begun his studies as a cadet, however, when tragedy shattered his adored father’s career. He was forced to resign by the wave of anti-German hysteria which swept Britain after the outbreak of World War I. His heartbroken father changed his family name from Battenberg to Mountbatten at King George V’s request and was created Marquess of Milford Haven. The First Sea Lord’s equally affected son vowed to fill one day the post from which an unjust outcry had driven his father.

During the long years between the wars, however, his career had followed the slow, unspectacular path of a peacetime officer. It was in other, less martial fields that the young Mountbatten had made his impression on the public. With his charm, his remarkable good looks, his infectious gaiety, he was one of the darlings of Britain’s penny press, catering to a world desperate for glamour after the horrors of war. His marriage to Edwina Ashley, a beautiful and wealthy heiress, with the Prince of Wales as his best man, was the social event of 1922.

Rare were the Sunday papers over the next years that did not contain a photograph or some mention of Louis and Edwina Mountbatten, the Mountbattens at the theatre with Noël Coward, the Mountbattens at the Royal Enclosure at Ascot, dashing young Lord Louis water-skiing in the Mediterranean or receiving a trophy won playing polo.

They constituted an image Mountbatten never denied; he revelled in every dance, party and polo match. But beneath that public image there was another figure of which the public was unaware. It emerged when the dancing was over.

The glamorous young man had not forgotten his boyhood vow. Mountbatten was an intensely serious, ambitious, and dedicated naval officer. He possessed an awesome capacity for work, a trait which would leave his subordinates gasping all his life. Convinced that future warfare would be patterned by the dictates of science and won by superior communications, Mountbatten eschewed the more social career of a deck officer to study signals.

He came out top of the Navy Higher Wireless Course in 1927, then sat down to write the first comprehensive manual for all the wireless sets used by the Navy. He was fascinated by the fast-expanding horizons of technology and plunged himself into the study of physics, electricity and communications in every form. New techniques, new ideas, were his passions and his playthings.

He obtained for the Royal Navy the works of a brilliant French rocketry expert, Robert Esnault Pelterie. Their pages gave Britain an eerily accurate forecast of the V-bomb, guided missiles and even man’s first flight to the moon. In Switzerland, he ferreted out a fast-firing anti-aircraft gun designed to stop the Stuka dive bomber; then spent months forcing the reluctant Royal Navy to adopt it.

He had followed the rise of Hitler and German rearmament with growing apprehension. He had also watched with pained but perceptive eyes the evolution of the society that had driven his beloved uncle Nicholas II from the throne of the Tsars. Increasingly, as the thirties wore on, Mountbatten and his wife spent less and less time on the dance floor, and more and more in a crusade to awaken friends and politicians to the conflict both saw was coming.

On 25 August 1939, a proud Mountbatten took command of a newly commissioned destroyer, HMS Kelly. A few hours later the radio announced Hitler and Stalin had signed a non-aggression pact. The Kelly’s captain understood the import of the announcement immediately. Mountbatten ordered his crew to work day and night to reduce the three weeks needed to ready the ship for sea.

Nine days later, when war broke out, the captain of the Kelly was slung over the ship’s side in a pair of dirty overalls, sloshing paint on her hull along with his able seamen. The next day, however, the Kelly was in action against a German submarine.

‘I will never give the order “Abandon ship”,’ Mountbatten promised his crew. ‘The only way we will ever leave this ship is if she sinks under our feet.’

The Kelly escorted convoys through the channel, hunted U-boats in the North Sea, dashed through fog and German bombers to help rescue six thousand survivors of the Narvik expedition at the head of the Namsos Fiord in Norway. Her stern was damaged at the mouth of the Tyne and her boiler room devastated by a torpedo in the North Sea. Ordered to scuttle, Mountbatten refused, spent a night alone on the drifting wreck, then, with eighteen volunteers, brought her home under tow.

A year later, in May 1941, off Crete, the Kelly’s luck ran out. She took a bomb in her magazine and went down in minutes. Faithful to his vow, Mountbatten stayed on her bridge until she rolled over, then fought his way to the surface. For hours, he held the oil-spattered survivors around a single life raft, leading them in singing ‘Roll Out the Barrel’ while German planes strafed them. Mountbatten won the DSO for his exploits on the Kelly and the ship a bit of immortality in the film In Which We Serve, made by Mountbatten’s friend Noël Coward.

Five months later, Churchill, searching for a bold young officer to head Combined Operations, the commando force created to develop the tactics and technology that would eventually bring the Allies back to the continent, called on Mountbatten. The assignment proved ideal for his blend of dash and scientific curiosity. Vowing he was a man who would never say no to an idea, he opened his command to a parade of inventors, scientists, technicians, geniuses and mountebanks. Some of their schemes, like an iceberg composed of frozen sea water mixed with five per cent wood pulp to serve as a floating and unsinkable airfield, were wild fantasies. But they also produced Pluto, the underwater trans-channel pipeline, the Mulberry artificial harbours and the landing and rocket craft designs that made the Normandy invasion possible. For their leader, they ultimately produced his extraordinary elevation to Supreme Command of South-east Asia at the age of 43.

Now preparing to take on the most challenging task of his career, Mountbatten was at the peak of his physical and intellectual powers. The war at sea and high command had given him a capacity for quick decision and brought out his natural talent for leadership. He was not a philosopher or an abstract thinker, but he possessed an incisive, analytical mind honed by a lifetime of hard work. He had none of the Anglo-Saxon affection for the role of the good loser. He believed in winning. As a young officer, his crews had once swept the field in a navy regatta because he had taught them an improved rowing technique. Criticized later for the style he’d introduced, he had acidly observed that he thought the important thing was ‘crossing the finishing line first’.

His youthful gaiety had matured into an extraordinary charm and a remarkable facility for bringing people together. ‘Mountbatten’, remarked a man who was not one of his admirers, ‘could charm a vulture off a corpse if he set his mind to it.’

Above all, Mountbatten was endowed with an endless reservoir of self-confidence, a quality his detractors preferred to label conceit. When Churchill had offered him his Asian command, he had asked for 24 hours to ponder the offer.

‘Why,’ snarled Churchill, ‘don’t you think you can do it?’

‘Sir,’ replied Mountbatten, ‘I suffer from the congenital weakness of believing I can do anything.’

Victoria’s great-grandson would need every bit of that self-confidence in the weeks ahead.

Penitent’s Progress I

At every village, his routine was the same. As soon as he arrived, the most famous Asian alive would go up to a hut, preferably a Moslem’s hut, and beg for shelter. If he was turned away, and sometimes he was, Gandhi would go to another door. ‘If there is no one to receive me,’ he had said, ‘I shall be happy to rest under the hospitable shade of a tree.’

Once installed, he lived on whatever food his hosts could offer: mangoes, vegetables, goat’s curds, green coconut milk. Every hour of his day in each village was rigorously programmed. Time was one of Gandhi’s obsessions. Each minute, he held, was a gift of God to be used in the service of man. His own days were ordered by one of his few possessions, a sixteen-year-old, eight-shilling Ingersoll watch that was always tied to his waist with a piece of string. He got up at two o’clock in the morning to read his Gita and say his morning prayers. From then until dawn he squatted in his hut, patiently answering his correspondence in longhand by pencil. He used each pencil right down to an ungrippable stub because, he held, it represented the work of a fellow human being and to waste it would indicate indifference to his labours. Every morning at a rigidly appointed hour, he gave himself a salt and water enema. A devout believer in nature cures, Gandhi was convinced that was the way to flush the toxins from his bowels. For years, the final sign a man had been accepted in his company, came when the Mahatma himself offered to give him a salt and water enema.

At sun-up, Gandhi began to wander the village, talking and praying incessantly with its inhabitants. Soon he developed a tactic to implement his drive to return peace and security to Noakhali. It was a typically Gandhian ploy. In each village he would search until he’d found a Hindu and a Moslem leader who’d responded to his appeal. Then he’d persuade them to move in together under one roof. They would become the joint guarantors of the village’s peace. If his fellow Moslems assailed the village’s Hindus, the Moslem promised to undertake a fast to death. The Hindu made a similar pledge.

But on those blood-spattered byways of Noakhali, Gandhi did not limit himself to trying to exorcise the hatred poisoning the villages through which he passed. Once he sensed a village was beginning to understand his message of fraternal love, he broadened the dimension of his appeal. India for Gandhi was its lost and inaccessible villages, like those hamlets along his route in Noakhali. He knew them better than any man alive. He wanted his independent India built on the foundation of her re-invigorated villages, and he had his own ideas on how to re-order the patterns of their existence.

‘The lessons which I propose to give you during my tour are how you can keep the village water and yourselves clean,’ he would tell the villagers; ‘what use you can make of the earth, of which your bodies are made; how you can obtain the life force from the infinite sky over your heads; how you can reinforce your vital energy from the air which surrounds you; how you can make proper use of sunlight.’

The ageing leader did not satisfy himself with words. Gandhi had a tenacious belief in the value of actions. To the despair of many of his followers, who thought a different set of priorities should order his time, Gandhi would devote the same meticulous care and attention to making a mudpack for a leper as preparing for an interview with a Viceroy. So, in each village he would go with its inhabitants to their wells. Frequently he would help them find a better location for them. He would inspect their communal latrines, or if, as was most often the case, they didn’t have any, he would teach them how to build one, often joining in the digging himself. Convinced bad hygiene was the basic cause of India’s terrible mortality rate, he’d inveighed for years against such habits as public defecation, spitting, and blowing out nostrils on the paths where most of the village poor walked barefoot.

‘If we Indians spat in unison,’ he had once sighed, ‘we would form a puddle large enough to drown three hundred thousand Englishmen.’ Every time he saw a villager spitting or blowing his nose on a footpath, he would gently reprimand him. He went into homes to show people how to build a simple filter of charcoal and sand to help purify their drinking water. ‘The difference between what we do and what we could do,’ he constantly repeated, ‘would suffice to solve most of the world’s problems.’

Every evening he held an open prayer meeting, inviting Moslems to join in, being careful to recite as part of each day’s service verses from the Koran. Anyone could question him on anything at those meetings. One day a villager remonstrated with him for wasting his time in Noakhali when he should have been in New Delhi negotiating with Jinnah and the Moslem League.

‘A leader,’ Gandhi replied, ‘is only a reflection of the people he leads.’ The people had first to be led to make peace among themselves. Then, he said, ‘their desire to live together in peaceful neighbourliness will be reflected by their leaders.’

When he felt a village had begun to understand his message, when its Moslem community had agreed to let its frightened Hindus return to their homes, he set out for the next hamlet, five, ten, fifteen miles away. Inevitably, his departure took place at precisely 7.30. As at Srirampur, the little party would march off, Gandhi at its head, through the mango orchards, the green scum-slicked ponds where ducks and wild geese went honking skywards at their approach. Their paths were narrow, winding their way through palm groves and the underbush. They were littered with stones, pebbles, protruding roots. Sometimes the little procession had to struggle through ankle-deep mud. By the time they reached their next stop, the 77-year-old Mahatma’s bare feet were often aching with chilblains, or disfigured by bleeding sores and blisters. Before taking up his task again, he soaked them in hot water. Then, Gandhi indulged in the one luxury of his penitent’s tour. His great-niece and constant companion, Manu, massaged his martyred feet – with a stone.

For thirty years those battered feet had led the famished hordes of a continent in prayer towards their liberty. They had carried Gandhi into the most remote corners of India, to thousands of villages like those he now visited, to lepers’ wading pools, to the worst slums of his nation, to palaces and prisons, in quest of his cherished goal, India’s freedom.

Mohandas Gandhi had been an eight-year-old schoolboy when the great-grandmother of the two cousins sipping their tea in Buckingham Palace had been proclaimed Empress of India on a plain near Delhi. For Gandhi, that grandiose ceremony was always associated with a jingle he and his playmates had chanted to mark the event in his home town of Porbandar, 700 miles from Delhi on the Arabian Sea:

Behold the mighty Englishman!

He rules the Indian small

Because being a meat eater

He is five cubits tall.

The boy whose spiritual force would one day humble those five-cubit Englishmen and their enormous empire could not resist the challenge in the jingle. With a friend, he cooked and ate a forbidden piece of goat’s meat. The experiment was disastrous. The eight-year-old Gandhi promptly vomited up the goat and spent the night dreaming the animal was cavorting in his stomach.

Gandhi’s father was the hereditary diwan, prime minister, of a tiny state on the Kathiawar peninsula near Bombay and his mother an intensely devout woman given to long religious fasts.

Curiously, Gandhi, destined to become India’s greatest spiritual leader of modern times, was not born into the Brahmin caste that was supposed to provide Hinduism with its hereditary philosophical and religious elite. His father was a member of the vaisyas, the caste of shopkeepers and petty tradesmen which stood halfway up the Hindu social scale, above Untouchable and sudras, artisans, but below Brahmins and kashatriyas, warriors.

At thirteen, Gandhi, following the Indian tradition of the day, was married to an illiterate stranger named Kasturbai. The youth who was later to offer the world a symbol of ascetic purity revelled in the consequent discovery of sex.

Four years later, Gandhi and his wife were in the midst of enjoying its pleasures when a rap on the door interrupted their lovemaking. It was a servant. Gandhi’s father, he announced, had just died.

Gandhi was horrified. He was devoted to his father. Moments before he’d been by the bed on which his father lay dying, patiently massaging his legs. An urgent burst of sexual desire had seized him and he’d tiptoed from his father’s room to wake up his pregnant wife. The joy of sex began to fade for Gandhi. An indelible stamp had been left on his psyche.

As a result of his father’s death, Gandhi was sent to England to study law so he might become prime minister of a princely state. It was an enormous undertaking for a devout Hindu family. No member of Gandhi’s family had ever gone abroad before. Gandhi was solemnly pronounced an outcast from his shopkeepers’ caste, because, to his Hindu elders, his voyage across the seas would leave him contaminated.

Gandhi was wretchedly unhappy in London. He was so desperately shy that to address a single word to a stranger was a painful ordeal; to produce a full sentence agony. Physically, at nineteen he was a pathetic little creature in the sophisticated world of the Inns of Court. His cheap, badly-cut Bombay clothes flopped over his undersized body like loose sails on a becalmed ship. Indeed, he was so small, so unremarkable, his fellow students sometimes took him for an errand boy.

The lonely, miserable Gandhi decided the only way out of his agony was to become an English gentleman. He threw away his Bombay clothes and got a new wardrobe. It included a silk top-hat, an evening suit, patent-leather boots, white gloves and even a silver-tipped walking stick. He bought hair lotion to plaster his unwilling black hair on to his skull. He spent hours in front of a mirror contemplating his appearance and learning to tie a tie. To win the social acceptance he longed for, he bought a violin, joined a dancing class, hired a French tutor and an elocution teacher.

The results of that poignant little charade were as disastrous as his earlier encounter with goat’s meat. The only sound he learned to coax from his violin was a dissonant wail. His feet refused to acknowledge three-quarter time, his tongue the French language, and no amount of elocution lessons were going to free the spirit struggling to escape from under his crippling shyness. Even a visit to a brothel was a failure. Gandhi couldn’t get past the parlour.

He gave up his efforts to become an Englishman and went back to being himself. When finally he was called to the bar, Gandhi rushed back to India with undisguised relief.

His homecoming was less than triumphant. For months, he hung around the Bombay courts looking for a case to plead. The young man whose voice would one day inspire 300 million Indians proved incapable of articulating the phrases necessary to impress a single Indian magistrate.

That failure led to the first great turning point in Gandhi’s life. His frustrated family sent him to South Africa to unravel the legal problems of a distant kinsman. His trip was to have lasted a few months; he stayed over twenty years. There, in that bleak and hostile land, Gandhi found the philosophical principles that transformed his life and Indian history.

Nothing about the young Gandhi walking down a gangplank in Durban harbour in May 1893, however, indicated a vocation for asceticism or saintliness. The future prophet of poverty made his formal entry on to the soil of South Africa in a high white collar and the fashionable frock coat of a London Inner Temple barrister, his brief-case crammed with documents on the rich Indian businessman whose interests he’d come to defend.

Gandhi’s real introduction to South Africa came a week after his arrival on an overnight train ride from Durban to Pretoria. Four decades later Gandhi would still remember that trip as the most formative experience of his life. Halfway to Pretoria a white man stalked into his first-class compartment and ordered him into the baggage car. Gandhi, who held a first-class ticket, refused. At the next stop the white called a policeman and Gandhi with his luggage was unceremoniously thrown off the train in the middle of the night.

All alone, shivering in the cold because he was too shy to ask the station master for the overcoat locked in his luggage, Gandhi passed the night huddled in the unlit railroad station, pondering his first brutal confrontation with racial prejudice. Like a medieval youth during the vigil of his knighthood, Gandhi sat praying to the God of the Gita for courage and guidance. When dawn finally broke on the little station of Maritzburg, the timid, withdrawn youth was a changed person. The little lawyer had reached the most important decision of his life. Mohandas Gandhi was going to say ‘no’.

A week later, Gandhi delivered his first public speech to Pretoria’s Indians. The advocate who’d been so painfully shy in the courtrooms of Bombay had begun to find his tongue. He urged the Indians to unite to defend their interests and, as a first step, to learn how to do it in their oppressors’ English tongue. The following evening, without realizing it, Gandhi began the work that would ultimately bring India freedom by teaching English grammar to a barber, a clerk and a shopkeeper. Soon he had also won the first of the successes which would be his over the next half-century. He wrung from the railway authorities the right for well-dressed Indians to travel first- or second-class on South Africa’s railways.

Gandhi decided to stay on in South Africa when the case which had sent him there had been resolved. He became both the champion of South Africa’s Indian community and a highly successful lawyer. Loyal to the British Empire despite its racial injustice, he even led an ambulance corps in the Boer War.

Ten years after his arrival in South Africa, another long train ride provoked the second great turning point in Gandhi’s life. As he boarded the Johannesburg-Durban train one evening in 1904, an English friend passed Gandhi a book to read on the long trip, John Ruskin’s Unto This Last.

All night Gandhi sat up reading as his train rolled through the South African veldt. It was his revelation on the road to Damascus. By the time his train reached Durban the following morning, Gandhi had made an epic vow: he was going to renounce all his material possessions and live his life according to Ruskin’s ideals.

Riches, Ruskin wrote, were just a tool to secure power over men. A labourer with a spade served society as truly as a lawyer with a brief, and the life of labour, of the tiller of the soil, is the life worth living.

Gandhi’s decision was all the more remarkable because he was, at that moment, a wealthy man earning over £5000 a year from his law practice, an enormous sum in the South Africa of the time.

For two years, however, doubts had been fermenting in Gandhi’s mind. He was haunted by the Bhagavad Gita’s doctrine of renunciation of desire and attachment to material possessions as the essential stepping-stone to a spiritual awakening. He had already made experiments of his own: he had started to cut his own hair, do his laundry, clean his own toilet. He had even delivered his last child. His doubts found their confirmation in Ruskin’s pages.

Barely a week later, Gandhi settled his family and a group of friends on a hundred-acre farm near Phoenix, fourteen miles from Durban. There, on a sad, scrubby site consisting of a ruined shack, a well, some orange, mulberry and mango trees, and a horde of snakes, Gandhi’s life took on the pattern that would rule it until his death: a renunciation of material possessions and a striving to satisfy human needs in the simplest manner, coupled with a communal existence in which all labour was equally valuable and all goods were shared.

One last, painful renunciation remained, however, to be made. It was the vow of Brahmacharya, the pledge of sexual continence and it had haunted Gandhi for years.

The scar left by his father’s death, a desire to have no more children, his rising religious consciousness all drove him towards his decision. One summer evening in 1906 Gandhi solemnly announced to his wife, Kasturbai, that he had taken the vow of Brahmacharya. Begun in a joyous frenzy at the age of thirteen, the sexual life of Mohandas Gandhi had reached its conclusion at the age of 37.

To Gandhi, however, Brahmacharya meant more than just the curbing of sexual desires. It was the control of all the senses. It meant restraint in emotion, diet, and speech, the suppression of anger, violence and hate, the attainment of a desireless state close to the Gita’s ideal of non-possession. It was his definitive engagement on the ascetic’s path, the ultimate act of self-transformation. None of the vows Gandhi took in his life would force upon him such intense internal struggle as his vow of chastity. It was a struggle which, in one form or another, would be with him for the rest of his life.

It was, however, in the racial struggle he’d undertaken during his first week in South Africa that Gandhi enunciated the two doctrines which would make him world-famous: nonviolence and civil disobedience.

It was a passage from the Bible which had first set Gandhi meditating on non-violence. He had been overwhelmed by Christ’s admonition to his followers to turn the other cheek to their aggressors. The little man had already applied the doctrine himself, stoically submitting to the beatings of numerous white aggressors. The philosophy of an eye for an eye led only to a world of the blind, he reasoned. You don’t change a man’s convictions by chopping off his head or infuse his heart with a new spirit by putting a bullet through it. Violence only brutalizes the violent and embitters its victims. Gandhi sought a doctrine that would force change by the example of the good, reconcile men with the strength of God instead of dividing them by the strength of man.

The South African government furnished him an opportunity to test his still half-formulated theories in the autumn of 1906. The occasion was a law which would have forced all Indians over the age of eight to register with the government, be fingerprinted and carry special identity cards. On 11 September, before a gathering of angry Indians in the Empire Theatre in Johannesburg, Gandhi took the stand to protest against the law.

To obey it, he said, would lead to the destruction of their community. ‘There is only one course open to me,’ he declared, ‘to die but not to submit to the law.’ For the first time in his life he led a public assembly in a solemn vow before God to resist an unjust law, whatever the consequences. Gandhi did not explain to his audience how they would resist the law. Probably he himself did not know. Only one thing was clear; it would be resisted without violence.

The new principle of political and social struggle born in the Empire Theatre soon had a name, Satyagraha, Truth Force. Gandhi organized a boycott of the registration procedures and peaceful picketing of the registration centres. His actions earned him the first of his life’s numerous jail sentences.

While in jail, Gandhi encountered the second of the secular works which would deeply influence his thought, Henry Thoreau’s essay On Civil Disobedience.* Protesting against a US government that condoned slavery and was fighting an unjust war in Mexico, Thoreau asserted the individual’s right to ignore unjust laws and refuse his allegiance to a government whose tyranny had become unbearable. To be right, he said, was more honourable than to be law-abiding.

Thoreau’s essay was a catalyst to thoughts already stirring in Gandhi. Released from jail, he decided to apply them in protest against a decision of the Transvaal to close its borders to Indians. On 6 November 1913, 2037 men, 127 women, and 57 children, Gandhi at their head, staged a non-violent march on the Transvaal’s frontiers. Their certain destiny was jail, their only sure reward a frightful beating.

Watching that pathetic, bedraggled troop walking confidently along behind him, Gandhi experienced another illuminating revelation. Those wretches had nothing to look forward to but pain. Armed white vigilantes waited at the border, perhaps to kill them. Yet fired by faith in him and the cause to which he’d called them, they marched in his footsteps, ready, in Gandhi’s words, to ‘melt their enemies’ hearts by self-suffering’.

Gandhi suddenly sensed in their quiet resolution what mass, non-violent action might become. There on the borders of the Transvaal he realized the enormous possibilities inherent in the movement he’d provoked. The few hundreds behind him that November day could become hundreds of thousands, a tide rendered irresistible by an unshakeable faith in the nonviolent ideal.

Persecution, flogging, jailing, economic sanctions followed their action, but they could not break the movement. His African crusade ended in almost total victory in 1914. He could go home at last.

The Gandhi who left South Africa in July 1914 was a totally different person from the timid young lawyer who’d landed in Durban. He had discovered on its inhospitable soil his three teachers, Ruskin, Tolstoy and Thoreau. From his experience he had evolved the two doctrines, non-violence and civil disobedience, with which, over the next thirty years, he would humble the most powerful empire in the world.

An enormous crowd gave Gandhi a hero’s welcome when his diminutive figure passed under the spans of Bombay’s Gateway of India on 9 January 1915. The spare suitcase of the leader passing under that imperial archway contained one significant item. It was a thick bundle of paper covered with Gandhi’s handwritten prose. Its title Hind Swaraj – ‘Indian Home Rule’, made one thing clear. Africa, for Gandhi, had been only a training ground for the real battle of his life.

Gandhi settled near the industrial city of Ahmedabad on the banks of the Sabarmati River where he founded an ashram, a communal farm similar to those he’d founded in South Africa. As always, Gandhi’s first concern was for the poor. He organized the indigo farmers of Bihar against the oppressive exactions of their British landlords, the peasants of the drought-stricken province of Bombay against their taxes, the workers in Ahmedabad’s textile mills against the employers whose contributions sustained his ashram. For the first time, an Indian leader was addressing himself to the miseries of India’s masses. Soon Rabindranath Tagore, India’s Nobel Prizewinner, conferred on Gandhi the appellation he would carry for the rest of his life, ‘Mahatma’. ‘The Great Soul in Beggar’s Garb’, he called him.

Like most Indians, Gandhi was loyal to Britain in World War I, convinced Britain in return would give a sympathetic hearing to India’s nationalist aspirations. Gandhi was wrong. Britain instead passed the Rowlatt Act in 1919, to repress agitation for Indian freedom. For weeks Gandhi meditated, seeking a tactic with which to respond to Britain’s rejection of India’s hopes. The idea for a reply came to him in a dream. It was brilliantly, stunningly simple. India would protest, he decreed, with silence, a special eerie silence. He would do something no one had ever dreamed of doing before; he would immobilize all India in the quiet chill of a day of mourning, a hartal.

Like so many of Gandhi’s political ideas, the plan reflected his instinctive genius for tactics that could be enunciated in few words, understood by the simplest minds, put into practice with the most ordinary gestures. To follow him, his supporters did not have to break the law or brave police clubs. They had only to do nothing. By closing their shops, leaving their classrooms, going to their temples to pray or just staying at home, Indians could demonstrate their solidarity with his protest call. He chose 7 April 1919 as the day of his hartal. It was his first overt act against the Government of India. Let India stand still, he urged, and let India’s oppressors listen to the unspoken message of her silent masses.

Unfortunately, those masses were not everywhere silent. Riots erupted. The most serious were in Amritsar in the Punjab. To protest against the restrictions clamped on their city as a result, thousands of Indians gathered on 13 April, for a peaceful but illegal meeting in a stone- and debris-littered compound called Jallianwalla Bagh.

There was only one entrance to the compound down a narrow alley between two buildings. Through it, just after the meeting had begun, marched Amritsar’s Martial Law Commander, Brigadier R. E. Dyer, at the head of fifty soldiers. He stationed his men on either side of the entry and, without warning, opened fire with machine-guns on the defenceless Indians. For ten full minutes, while the trapped Indians screamed for mercy, the soldiers fired. They fired 1650 rounds. Their bullets killed or wounded 1516 people. Convinced he’d ‘done a jolly good thing’, Dyer marched his men back out of the Bagh.

His ‘jolly good thing’ was a turning point in the history of Anglo-Indian relations, more decisive even than the Indian Mutiny 63 years before.* For Gandhi it was the final breach of faith by the empire for which he had compromised his pacifist principles. He turned all his efforts to taking control of the organization which had become synonymous with India’s nationalist aspirations.

The idea that the Congress Party might one day become the focal point of mass agitation against British rule in India would surely have horrified the dignified English civil servant who had founded the party in 1885. Acting with the blessings of the Viceroy, Octavian Hume had sought to create an organization which would canalize the protests of India’s slowly growing educated classes into a moderate, responsible body prepared to engage in gentlemanly dialogue with India’s English rulers.

That was exactly what Congress was when Gandhi arrived on the political scene. Determined to convert it into a mass movement attuned to his non-violent creed, Gandhi presented the party with a plan of action in Calcutta in 1920. It was adopted by an overwhelming majority. From that moment until his death, whether he held rank in the party or not, Gandhi was Congress’s conscience and its guide, the unquestioned leader of the independence struggle.

Like his earlier call for a national hartal, Gandhi’s new tactic was electrifyingly simple, a one word programme for political revolution: non-co-operation. Indians, he decreed, would boycott whatever was British: students would boycott British schools; lawyers, British courts; employees, British jobs; soldiers, British honours. Gandhi himself gave the lead by returning to the Viceroy the two medals he’d earned with his ambulance brigade in the Boer War.

Above all, his aim was to weaken the edifice of British power in India by attacking the economic pillar upon which it reposed. Britain purchased raw Indian cotton for derisory prices, shipped it to the mills of Lancashire to be woven into textiles, then shipped the finished products back to India to be sold at a substantial profit in a market which virtually excluded non-British textiles. It was the classic cycle of imperialist exploitation, and the arm with which Gandhi proposed to fight it was the very antithesis of the great mills of the Industrial Revolution that had sired that exploitation. It was a primitive wooden spinning-wheel.

For the next quarter of a century Gandhi struggled with tenacious energy to force all India to forsake foreign textiles for the rough cotton khadi spun by millions of spinning-wheels. Convinced the misery of India’s countryside was due above all to the decline in village crafts, he saw in a renaissance of cottage industry heralded by the spinning-wheel the key to the revival of India’s impoverished countryside. For the urban masses, spinning would be a kind of spiritual redemption by manual labour, a constant, daily reminder of their link to the real India, the India of half a million villages.

The wheel became the medium through which he enunciated a whole range of doctrines close to his heart. To it, he tied a crusade to get villagers to use latrines instead of the open fields, to improve hygiene and health by practising cleanliness, to fight malaria, to set up simple village schools for their offspring, to preach Hindu-Moslem harmony: in short an entire programme to regenerate India’s rural life.

Gandhi himself gave the example by regularly consecrating half an hour a day to spinning and forcing his followers to do likewise. The spinning ritual became a quasi-religious ceremony; the time devoted to it, an interlude of prayer and contemplation. The Mahatma began to murmur: ‘Rama, Rama, Rama’ (God) in rhythm to the click – click – click of the spinning-wheel.

In September 1921, Gandhi gave a final impetus to his campaign by solemnly renouncing for the rest of his life any clothing except a homespun loincloth and a shawl. The product of the wheel, cotton khadi, became the uniform of the independence movement, wrapping rich and poor, great and small, in a common swathe of rough white cloth. Gradually Gandhi’s little wooden wheel became the symbol of his peaceful revolution, of an awakening continent’s challenge to Western imperialism.

Splashing through ankle-deep mud and water, on precarious, rock-strewn paths, sleeping endless nights on the wooden planks of India’s third-class railway carriages, Gandhi travelled to the most remote corners of India preaching his message. Speaking five or six times a day, he visited thousands of villages.

It was an extraordinary spectacle. Gandhi would lead the march, barefoot, wrapped in his loincloth, spectacles sliding from his nose, clomping along with the aid of a bamboo stave. Behind him came his followers in identical white loincloths. Closing the march, hoist like some triumphant trophy over a follower’s head, rode the Mahatma’s portable toilet, a graphic reminder of the importance he attached to sound sanitation.

His crusade was an extraordinary success. The crowds rushed to see the man already known as a ‘Great Soul’. His voluntary poverty, his simplicity, his humility, his saintly air made him a kind of Holy Man, marching out of some distant Indian past to liberate a new India.

In the towns he told the crowds that, if India was to win self-rule, she would have to renounce foreign clothing. He asked for volunteers to take off their clothes and throw them in a heap at his feet. Shoes, socks, trousers, shirts, hats, coats cascaded into the pile until some men stood stark naked before Gandhi. With a delighted smile Gandhi then set the pile ablaze, a bizarre bonfire of ‘Made in England’ clothing.

The British were quick to react. If they hesitated to arrest Gandhi for fear of making him a martyr, they struck hard at his followers. Thirty thousand people were arrested, meetings and parades broken up by force, Congress offices ransacked. On 1 February 1922, Gandhi courteously wrote to the Viceroy to inform him he was intensifying his action. Non-co-operation was to be escalated to civil disobedience. He counselled peasants to refuse to pay taxes, city dwellers to ignore British laws and soldiers to stop serving the crown. It was Gandhi’s non-violent declaration of war on India’s colonial government.

‘The British want us to put the struggle on the plane of machine-guns where they have the weapons and we do not,’ he warned. ‘Our only assurance of beating them is putting the struggle on a plane where we have the weapons and they have not.’

Thousands of Indians followed his call and thousands more went off to jail. The beleaguered governor of Bombay called it ‘the most colossal experiment in world history and one which came within an inch of succeeding’.

It failed because of an outburst of bloody violence in a little village north-east of Delhi. Against the wishes of almost his entire Congress hierarchy, Gandhi called off the movement because he felt his followers did not yet fully understand nonviolence.

Sensing that his change of attitude had rendered him less dangerous, the British arrested him. Gandhi pleaded guilty to the charge of sedition, and in a moving appeal to his judge, asked for the maximum penalty. He was sentenced to six years in Yeravda prison near Poona. He had no regrets. ‘Freedom,’ he wrote, ‘is often to be found inside a prison’s walls, even on a gallows; never in council chambers, courts and classrooms.’

Gandhi was released before the end of his sentence because of ill-health. For three years, he travelled and wrote, patiently training his followers, inculcating the principles of nonviolence to avoid a recurrence of the outburst that had shocked him before his arrest.

By the end of 1929, he was ready for another move forward. In Lahore, at the stroke of midnight, as the decade expired, he led his Congress in a vow for swaraj, nothing less than complete independence. Twenty-six days later, in gatherings all across India, millions of Congressmen repeated the pledge.

A new confrontation between Gandhi and the British was inevitable. Gandhi pondered for days waiting for his ‘Inner Voice’ to counsel him on the proper form of that confrontation. The answer proposed by his ‘Inner Voice’ was the finest fruit of his creative genius. So simple was the thought, so dramatic its execution, it made Gandhi world-famous overnight. Paradoxically, it was based on a staple the Mahatma had given up years before in his efforts to repress his sexual desires as part of his vow of chastity: salt.

If Gandhi spurned it, in India’s hot climate it was an essential ingredient in every man’s diet. It lay in great white sheets along the shore-lines, the gift of the eternal mother, the sea. Its manufacture and sale, however, was the exclusive monopoly of the state, which built a tax into its selling price. It was a small tax, but for a poor peasant it represented, each year, two weeks’ income.

On 12 March 1931, at 6.30 in the morning, his bamboo stave in his hand, his back slightly bent, his familiar loincloth around his hips, Gandhi marched out of his ashram at the head of a cortege of 79 disciples and headed for the sea, 241 miles away. Thousands of supporters from Ahmedabad lined the way and strewed the route with green leaves.

Newsmen rushed from all over the world to follow the progress of his strange caravan. From village to village the crowds knelt by the roadside as Gandhi passed. His pace was a deliberately tantalizing approach to his climax. To the British, it was infuriatingly slow. The weird, almost Chaplinesque image of a little, old, half-naked man clutching a bamboo pole, marching down to the sea to challenge the British Empire dominated the newsreels and press of the world day after day.

On 5 April, at six o’clock in the evening, Gandhi and his party finally reached the banks of the Indian Ocean near the town of Dandi. At dawn the next morning, after a night of prayer, the group marched into the sea for a ritual bath. Then Gandhi waded ashore and, before thousands of spectators, reached down to scoop up a piece of caked salt. With a grave and stern mien, he held his fist to the crowd, then opened it to expose in his palms the white crystals, the forbidden gift of the sea, the newest symbol in the struggle for Indian independence.

Within a week all India was in turmoil. All over the continent Gandhi’s followers began to collect and distribute salt. The country was flooded with pamphlets explaining how to make salt from sea water. From one end of India to another, bonfires of British cloth and exports sparkled in the streets.

The British replied with the most massive round-up in Indian history, sweeping people to jail by the thousands. Gandhi was among them. Before returning to the confines of Yeravda prison, however, he managed to send a last message to his followers.

‘The honour of India,’ he said, ‘has been symbolized by a fistful of salt in the hand of a man of non-violence. The fist which held the salt may be broken, but it will not yield up its salt.’

London, 18 February 1947

For three centuries, the walls of the House of Commons had echoed to the declarations of the handful of men who had assembled and guided the British Empire. Their debates and decisions had fixed the destiny of half a billion human beings scattered around the globe and helped impose the domination of a white, Christian, European elite on over a third of the earth’s inhabitable land surface.

Now, tensely expectant, the members of the House of Commons shivered in the melancholy shadows stretching out in dark pools from the corners of their unheated hall to hear their leader pronounce a funeral oration for the British Empire. His bulky figure swathed in a black overcoat, Winston Churchill slumped despondently on the Opposition benches. For four decades, since he had joined the Commons, his voice had given utterance in that hall to Britain’s imperial dream, just as, for the past decade, it had been the goad of England’s conscience, the catalyst of her courage.

He was a man of rare clairvoyance but inflexible in many of his convictions. He gloried in every corner of the realm but for none of them did he have sentiments comparable to those with which he regarded India. Churchill loved India with a violent and unreal affection. He had gone out there as a young subaltern with his regiment, the 4th Queen’s Own Hussars; played polo on the dusty maidans, gone pig-sticking and tiger hunting. He had climbed the Khyber Pass and fought the Pathans on the North-west Frontier. He was, forty-one years after his departure, still sending two pounds every month to the Indian who’d been his bearer for two years when he was a young subaltern. His gesture revealed much of his sentiments about India. He loved it first of all as a reflection of his own experience there and he loved the idea of doughty, upright Englishmen running the place with a firm, paternalistic hand.

His faith in the imperial dream was unshakeable. He had always maintained that Britain’s position in the world was determined by the Empire. He sincerely believed in the Victorian dogma that those ‘lesser breeds, without the law’ were better off under European rule than they would have been under the tyranny of local despots. Despite the perception he had displayed on so many world issues, India was a blind spot for Churchill. Nothing could shake his passionately held conviction that British rule in India had been just and exercised in India’s best interests; that her masses looked on their rulers with gratitude and affection; that the politicians agitating for independence were a petty-minded, half-educated elite, unreflective of the desires or interests of the masses. Churchill understood India, his own Secretary of State for India had noted acidly, ‘about as well as George III understood the American colonies’.

Since 1910 he had stubbornly resisted every effort to bring India towards independence. He contemptuously dismissed Gandhi and his Congress followers as ‘men of straw’. More than any other man in that chamber, Churchill was torn by the knowledge that his successor at 10 Downing Street was undertaking the task he had refused to contemplate, dismembering the Empire. If he and his Conservative Party had been defeated in 1945, however, they still commanded an absolute majority in the House of Lords. That gave him the power, if he chose to exercise it, to delay Indian independence by two full years. Distaste spreading like a rash over his glowering face, he watched the spare Socialist who’d succeeded him as Prime Minister rise to speak.

The brief text in Clement Attlee’s hand had been largely written by the young admiral he was sending to New Delhi to negotiate Britain’s departure from India and whose name he was about to reveal. Louis Mountbatten had, with characteristic boldness, proposed it as a substitute for the lengthy document Attlee himself had drafted. It defined the new Viceroy’s task in simple terms. Above all, it contained the new and salient point Mountbatten had maintained was essential if there was to be any hope of breaking the Indian log-jam. He had wrestled with Attlee for six weeks to nail it down with the precision he wanted.

The chilly assembly stirred as Attlee began to read the historic announcement. ‘His Majesty’s Government wishes to make it clear,’ he began, ‘that it is their definite intention to take the necessary steps to effect the transference of power into responsible Indian hands by a date not later than June 1948.’

A stunned silence followed as his words struck home to the men in the Commons. That they were the inevitable result of history and Britain’s own avowed course in India did not mitigate the sadness produced by the realization that barely fourteen months remained to the British Raj. An era in British life was ending. What the Manchester Guardian would call the following morning ‘the greatest disengagement in history’ was about to begin.

The bulky figure slumped on his bench rose when his turn came to protest, to hurl out one last eloquent plea for empire. Shaking slightly from cold and emotion, Churchill declared that the whole business was ‘an attempt by the government to make use of brilliant war figures in order to cover up a melancholy and disastrous transaction’.

By fixing a date for independence Attlee was adopting one of Gandhi’s ‘most scatter-brained observations – “Leave India to God” ’.

‘It is with deep grief,’ Churchill lamented, ‘that I watch the clattering down of the British Empire with all its glories and all the services it has rendered mankind. Many have defended Britain against her foes. None can defend her against herself … let us not add by shameful flight, by a premature, hurried scuttle – at least let us not add to the pangs of sorrow so many of us feel, the taint and sneer of shame.’

They were the words of a master orator, but they were also a futile railing against the setting of a sun. When the division bell rang, the Commons acknowledged the dictate of history. By an overwhelming majority, it voted to end British rule in India no later than June 1948.

Penitent’s Progress II

The deeper his little party penetrated into Noakhali’s bayous, the more difficult Gandhi’s mission became. The success he’d enjoyed with the Moslems in the first villages through which he’d passed had alerted the leaders in those that lay ahead. Sensing in it a challenge to their own authority, they had begun to stir the populace’s hostility to the Mahatma and his mission.

This morning, his pilgrim’s route took him past a Moslem school where seven- and eight-year-old children sat around their sheikh in an open-air classroom. Beaming like an excited grandfather rushing to embrace his favourite grandchildren, Gandhi hurried over to speak to the youngsters. The sheikh leapt up at his approach. With quick and angry gestures, he shooed his pupils into his hut, as though the old man approaching were a bogeyman come to cast some evil spell over them. Deeply pained by their flight, Gandhi stood before the doorway of the sheikh’s hut, making sad little waves of his hand to the children whose faces he could make out in the shadows. Dark eyes wide with curiosity and incomprehension, they stared back at him. Finally Gandhi touched his hand to his heart and sent them the Moslem greeting ‘salaam’. Not a single childish hand answered his pathetic sign. Gandhi turned away and resumed his march.

There had been other incidents. Four days before someone had sabotaged a bamboo support holding up a rickety bridge of bamboo poles over which Gandhi was due to cross. Fortunately, it had been discovered before the bridge could collapse and send Gandhi and his party tumbling into the muddy waters ten feet below. On another morning, his route had taken him through a grove of bamboo and coconut trees. Every tree seemed to be festooned with a banner proclaiming slogans like ‘Leave, you have been warned’, ‘Accept Pakistan’, or ‘Go for your own good’.

Those signs had no effect on Gandhi. Physical courage, the courage to accept without protest a beating, to face danger with quiet resolution was, Gandhi maintained, the prime characteristic required of a non-violent man. Since the first beating he’d received in South Africa, physical courage had been an attribute the frail Gandhi had displayed in abundance.

Muffling the inner sorrow the hostile signs and the children’s rejection had provoked, Gandhi trudged serenely towards his next stop. It had been a damp, humid night and the alluvial soil on the narrow path along which his party walked was slick and slippery under the heavy dew. Suddenly, the little procession came to a halt. At its head, Gandhi laid aside his bamboo stave and bent down. Some unknown Moslem hands had littered the track on which he was to walk barefoot with shards of glass and lumps of human excrement. Tranquilly, Gandhi broke off the branch of a stubby palm. With it, he stooped and humbly undertook the most defiling act a Hindu can perform. Using his branch as a broom, the 77-year-old penitent began to sweep that human excrement from his path.

For decades, the most persistent English foe of the elderly man patiently cleaning the faeces from his way had been the master orator of the House of Commons. Winston Churchill had uttered in his long career enough memorable phrases to fill a volume of prose, but few of them had imprinted themselves as firmly on the public’s imagination as those with which he had described Gandhi just sixteen years earlier, in February 1931: ‘half-naked fakir’.

The occasion that prompted Churchill’s outburst occurred on 17 February 1931. One hand holding his bamboo stave, the other clutching the edges of his white shawl, Mahatma Gandhi had that morning shuffled up the red sandstone steps to Viceroy’s House, New Delhi. He was still wan from his weeks in a British prison but the man who had organized the Salt March did not come to that house as a suppliant for the Viceroy’s favours. He came as India.

With his fistful of salt and his bamboo stave, Gandhi had rent the veil of the temple. So widespread had support for his movement become, that the Viceroy, Lord Irwin, had felt obliged to release him from prison and invite him to Delhi to treat with him as the acknowledged leader of the Indian masses. He was the first and the greatest in a line of Arab, African and Asian leaders who in the decades to come would follow his route from a British prison to a British conference chamber.

Winston Churchill had correctly read the portents of the meeting. He had assailed ‘the nauseating and humiliating spectacle of this one-time Inner Temple lawyer, now seditious fakir, striding half-naked up the steps of the Viceroy’s palace, there to negotiate and parley on equal terms with the representative of the King Emperor’.

‘The loss of India,’ he said with a clairvoyance that foreshadowed his speech sixteen years later, ‘would be final and fatal to us. It could not fail to be part of a process that would reduce us to the scale of a minor power.’

His words, however, had no impact on the negotiations in New Delhi. These covered eight meetings over three weeks and produced what became known as the Gandhi-Irwin pact. Its text read like a treaty between two sovereign powers, and that was the measure of Gandhi’s triumph. Under it, Irwin agreed to release from jail the thousands of Gandhi’s followers who’d followed their leader to prison.* Gandhi for his part agreed to call off his movement and attend a round table conference in London to discuss India’s future.

Six months later, to the astonishment of a watching British nation, Mahatma Gandhi walked into Buckingham Palace to take tea with the King Emperor dressed in a loincloth and sandals, a living portrayal of Kipling’s Gunga Din with ‘nothing much before and rather less than ’arf o’ that behind’. Later, when questioned on the appropriateness of his apparel, Gandhi replied with a smile ‘the king was wearing enough for both of us’.

The publicity surrounding their meeting was in a sense the measure of the real impact of Gandhi’s London visit. The round table conference he’d come to attend was a failure. London was not yet ready to contemplate Indian independence.

The real work Gandhi proclaimed lay ‘outside the conference … The seed which is being sown now may result in a softening of the British spirit.’ No one did more to soften it than Gandhi. The British press and public were fascinated by this man who wanted to overthrow their empire by turning the other cheek.

He had walked off his steamer in his loincloth carrying his bamboo stave. Behind him there were no aides-de-camp, no servants, only a handful of disciples and a goat, who tottered down the gangplank after Gandhi, an Indian goat to supply the Mahatma’s daily bowl of milk. He ignored the hotels of the mighty to live in a settlement house in London’s East End slums.

The man who had first come to London as an inarticulate tongue-tied student almost never stopped talking. He met Charlie Chaplin, Jan Smuts, George Bernard Shaw, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Harold Laski, Maria Montessori, coal miners, children, Lancashire textile workers thrown out of work by his campaigns in India; virtually everyone of importance except Winston Churchill, who adamantly refused to see him.

The impression Gandhi made was profound. The newsreels of the Salt March had already made him famous. To the masses of a Britain beset by industrial unrest, unemployment and grave social injustice, this messenger from the East in his Christ-like cotton sheet with his even more Christ-like message of love, was a fascinating and vaguely disturbing figure. Gandhi himself, perhaps, put his finger on the roots of much of that fascination in a radio broadcast to the USA.

World attention had been drawn to India’s freedom struggle, he said, ‘because the means adopted by us for attaining that liberty are unique … the world is sick unto death of blood-spilling. The world is seeking a way out and I flatter myself with the belief that perhaps it will be the privilege of the ancient land of India to show the way out to a hungering world.’

The western world Gandhi was visiting was not yet ready for the way out proposed by this revolutionary who travelled with a goat instead of a machine-gun. Already Europe’s streets echoed to the stomp of jackboots and the shrieks of impassioned ideologues. Nonetheless, when he left, thousands of French, Swiss and Italians flocked to the railroad stations on his route to the Italian port of Brindisi to gape at the frail, toothless man leaning from the window of his third-class compartment.

In Paris, so many people swarmed to the station that Gandhi had to climb on a baggage cart to address them. In Switzerland, where he visited his friend, the author Romain Rolland, the dairymen of Léman clamoured for the privilege of serving the ‘king of India’. In Rome, he warned Mussolini fascism would ‘collapse like a house of cards’, watched a football game and wept at the sight of the statue of Christ on the Cross in the Sistine Chapel.

Despite that triumphant progress across Europe, Gandhi suffered much on the voyage home. ‘I have come back empty-handed,’ he told the thousands who greeted him in Bombay. India would have to return to civil disobedience. Less than a week later the man who had been the King Emperor’s tea-time guest in London was once again His Imperial Majesty’s guest – this time back in Yeravda prison.

For the next three years, Gandhi was in and out of prison while in London Churchill thundered, ‘Gandhi and all he stands for must be crushed.’ Despite Churchill’s opposition, however, the British produced a basic reform for India offering her provinces some local autonomy, the Government of India Act of 1935. Finally released from jail, Gandhi turned from his political combat to devote three years to two projects particularly close to him, the plight of India’s millions of Untouchables and the situation in her villages.

With the approach of World War II, Gandhi became more convinced than ever that the non-violence which had been the guiding principle of India’s domestic struggle was the only philosophy capable of saving man from self-destruction.

When Mussolini overran Ethiopia, he urged the Ethiopians to ‘allow themselves to be slaughtered’. The result, he said, would be more effective than resistance since ‘after all, Mussolini didn’t want a desert’. Sickened by the Nazis’ persecution of the Jews, he declared: ‘If ever there could be justifiable war in the name of and for humanity, war against Germany to prevent the wanton persecution of a whole race would be completely justified.’

‘Still,’ he said, ‘I do not believe in war.’ He proposed ‘a calm and determined stand offered by unarmed men and women possessing the strength of suffering given to them by Jehovah.’ ‘That,’ he said, ‘would convert [the Germans] to an appreciation of human dignity.’

Not even the atrocities which were perpetrated in the concentration camps of Europe were to make him doubt the essential correctness of his attitude.

When war finally broke out, Gandhi prayed that the holocaust might at least produce, like some sudden burst of sunshine after the storm, the heroic gesture, the non-violent sacrifice, that would illuminate for mankind the path away from a tightening cycle of self-destruction.

While Churchill summoned his countrymen to ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’, Gandhi, hoping to find in the English a people brave enough to put his theory to the ultimate test, proposed another course. ‘Invite Hitler and Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions,’ he wrote to the English at the height of the blitz. ‘Let them take possession of your beautiful island with its many beautiful buildings. You will give all this, but neither your minds nor your souls.’

That course would have been a logical application of Gandhi’s doctrine. To the British, and above all to their indomitable leader, his words rang out like the gibberish of an irrelevant old fool.

Gandhi could not even convince the leadership of his own Congress movement that pacifism was the right course. Most of his followers were dedicated anti-fascists and anxious to take India into the fight if they could do so as free men. For the first time, but not the last, Gandhi and his disciples parted company.

It took Churchill to drive them back together. His position on India remained as rigid as ever. He refused to consider any of the compromises which would have allowed India’s Nationalists to join the war effort. When he held his first meeting with Franklin Roosevelt to frame the Atlantic Charter, he made it clear that, as far as he was concerned, India was not to fall under its generous provisions. His American partner was stunned by his sensitivity on the subject. Soon, another of his phrases was being repeated in the Allies’ councils: ‘I have not become His Majesty’s First Minister to preside over the dissolution of the British Empire.’

It was not until March 1942, when the Japanese Imperial Army was at India’s gates, that Churchill, under pressure from Washington and his own colleagues, sent a serious offer to New Delhi. To deliver it, he selected a particularly sympathetic courier, Sir Stafford Cripps, a vegetarian and austere Socialist with long, friendly relations with the Congress leadership. Considering its author, the proposal Cripps carried was remarkably generous. It offered the Indians the most Britain could be expected to concede in the midst of a war, a solemn pledge of what amounted to independence, dominion status, after Japan’s defeat. It contained, however, in recognition of the Moslem League’s increasingly strident calls for an Islamic state, a provision which could eventually accommodate their demand.

Forty-eight hours after his arrival, Gandhi told Cripps that the offer was unacceptable because it contemplated the ‘perpetual vivisection of India’. Besides, the British were offering India future independence to secure immediate Indian cooperation in the violent defence of Indian soil. That was not an agreement calculated to sway the apostle of non-violence. If the Japanese were to be resisted, it could be only in one way for Gandhi, non-violently.

The Mahatma cherished a secret dream. He was not opposed to the spilling of oceans of blood, provided it was done in a just cause. He saw rank on serried rank of disciplined, non-violent Indians marching out to die on the bayonets of the Japanese until that catalytic instant when the enormity of their sacrifice would overwhelm their foes, vindicate non-violence, and change the course of human history.

Churchill’s plan, he decreed, was ‘a post-dated cheque on a failing bank’. If he had nothing else to offer, Gandhi told Cripps, he might as well ‘take the next plane home’.*

The day after Cripps’ departure was a Monday, Gandhi’s ‘day of silence’, a ritual he had observed once a week for years to conserve his vocal chords and promote a sense of harmony in his being. Unhappily for Gandhi and for India, his ‘Inner Voice’, the voice of his conscience, was not observing a similar vigil. It spoke to Gandhi and the advice it uttered proved disastrous.

It came down to two words, the two words which became the slogan of Gandhi’s next struggle: ‘Quit India’. The British should drop the reins of power in India immediately, Gandhi proposed. Let them ‘leave India to God or even anarchy’. If the British left India to its fate the Japanese would have no reason to attack.

Just after midnight, 8 August 1942, in a stifling hot Bombay meeting hall, Gandhi, naked to the waist, sent out a call to arms to his followers of the All India Congress Committee. His voice was quiet and composed, but the words he uttered carried a passion and fervour uncharacteristic of Gandhi.

‘I want freedom immediately,’ he said, ‘this very night, before dawn if it can be had.’

‘Here is a mantra, a short one I give you,’ he told his followers. ‘“Do or die”. We shall either free India or die in the attempt; we shall not live to see the perpetuation of our slavery.’

What Gandhi got before dawn was not freedom but another invitation to a British jail. In a carefully prepared move the British swept Gandhi and the entire Congress leadership into prison for the duration of the war. A brief outburst of violence followed their arrest but, within three weeks, the British had the situation under control.

Gandhi’s tactic played into the hands of the Moslem League by sweeping his Congress leaders from the political scene at a crucial moment. While they languished in jail, their Moslem rivals supported Britain’s war effort, earning by their attitude a considerable debt of gratitude. Not only had Gandhi’s plan failed to get the English to quit India; it had gone a long way to making sure that, before leaving the country, they would feel compelled to divide it.