Читать книгу Freedom at Midnight: Inspiration for the major motion picture Viceroy’s House - Dominique Lapierre, Larry Collins - Страница 13

FOUR A Last Tattoo for the Dying Raj

ОглавлениеPenitent’s Progress III

Nothing could stop him. Fired by his unquenchable spirit, the old man drove his bare and aching feet from village to village, applying the balm of his love to India’s sores. Slowly, the wounds began to heal. In the wake of Gandhi’s wan and bent silhouette, the passions cooled. Timidly, uncertainly, peace spread its mantle over the blood-drenched marshes of Noakhali.

Its return did not end Gandhi’s suffering, however. A private drama had accompanied him on his march along those hate-filled footpaths, a drama whose dimensions would eventually scandalize some of his oldest associates, alarm millions of Indians, and baffle the historians who would one day attempt to comprehend all the facets of Mohandas Gandhi’s complex character. It would also produce one of the gravest personal crises in the life of the 77-year-old man who was the conscience of India.

Yet its roots were in no way sunk in the great political struggle of which he’d been the principal figure for a quarter of a century. They lay in that force which Gandhi had struggled to sublimate and control for forty years, sex. Its locus was a nineteen-year-old girl, Gandhi’s great-niece, Manu. Manu had been raised by Gandhi and his wife as their own granddaughter. She had nursed Kasturbai Gandhi on her deathbed and, before dying, Kasturbai had confided her to her husband’s care.

‘I’ve been a father to many,’ Gandhi promised the girl, ‘to you I am a mother.’ He fussed over her like a mother, supervising her dress, her diet, her education, her religious training. The problem which arose in Noakhali had begun in a conversation between them just before Gandhi set out on his pilgrimage. With the shyness of a young girl confessing something to her mother, Manu had admitted to Gandhi she had never felt the sexual impulses normal in a girl of her age.

To Gandhi, with his convoluted philosophy of sex, her words had special importance. Since he had sworn his own vow of chastity, Gandhi had maintained that sexual continence was the most important discipline his truly non-violent followers, male and female, had to master. His ideal non-violent army would be composed of sexless soldiers because otherwise, Gandhi feared, their moral strength would desert them at a critical moment.

Gandhi saw in Manu’s words the chance to make of her the perfect female votary. ‘If out of India’s millions of daughters, I can train even one into an ideal woman by becoming an ideal mother to you,’ he told her, ‘I shall have rendered a unique service to womankind.’ But first, he felt he had to be sure she was telling the truth. Only his closest collaborators were accompanying him in Noakhali, he informed her, but she would be welcome provided she submitted to his discipline and went through the test to which he meant to subject her.

They would, he decreed, share each night the crude straw pallet which passed for his bed. He regarded himself as a mother; she had said she found nothing but a mother’s love in him. If they were both truthful, if he remained firm in his ancient vow of chastity and she had never known sexual arousal, then they would be able to lie together in the innocence of a mother and daughter. If one of them was not being truthful, they would soon discover it.

If, however, Manu was being truthful then, Gandhi believed, she would flourish under his close and constant supervision. His own sexless state would stifle any residual desire still lurking in her. Pygmalion-like, a transformation would come over her. She would develop clarity of thought and firmness of speech. A new spirit would suffuse the girl, giving her a pure, crystalline devotion to the great task which awaited her.

Manu had accepted and her lithe figure had followed Gandhi’s traces across the swamp-lands of Noakhali. As Gandhi had known it would, his decision had immediately provoked the consternation of his little party.

‘They think all this is a sign of infatuation on my part,’ he told Manu after a few nights together. ‘I laugh at their ignorance. They do not understand.’

Very few people would. Only the purest of Gandhi’s followers would be able to follow the complex reasoning behind this latest manifestation of a great spiritual struggle, which for Gandhi, went all the way back to that evening in South Africa in 1906 when he had announced to his wife his decision to take the vow of Brahmacharya, chastity. In swearing that pledge,* Gandhi was setting out on a path almost as old as Hinduism itself. For countless centuries, a Hindu’s route to self-realization had passed by the sublimation of that vital force responsible for the creation of life. Only by forcing his sexual energy inward to fuel the furnace of his spiritual force, the Hindu ancients maintained, could a man achieve the spiritual intensity necessary to self-realization.

To aid men sworn to lead the chaste life, those Hindu sages had laid down a code of conduct for Brahmacharya called the nine-fold wall of protection. A true Brahmachari was not supposed to live among women, animals or eunuchs. He was not allowed to sit on the same mat with a woman or even gaze upon any part of a woman’s body. He was counselled to avoid the sensual blandishments of a hot bath, an oily massage or the alleged aphrodisiac properties of milk, curds, ghee or fatty foods.

Gandhi had not become chaste so as to live in a Himalayan cave, however. That kind of chastity involved little self-discipline or moral merit, he maintained. He had taken his vow because he firmly believed the sublimation of his sexual energies would give him the moral and spiritual power to accomplish his mission. His kind of Brahmachari was a man who had so suppressed his sexual urge that he could move normally in the society of women without feeling any sexual desire in himself or arousing it in them. A Brahmachari, he wrote, ‘does not flee the company of women’, because for him ‘the distinction between man and woman almost disappears’.

The real Brahmachari’s ‘sexual organs will begin to look different’, Gandhi declared. ‘They remain as mere symbols of his sex and his sexual secretions are sublimated into a vital force pervading his whole being.’ The perfect Brahmachari in Gandhi’s mind was a man who could ‘lie by the side even of a Venus in all her naked beauty, without being physically or mentally disturbed’.

It was an extraordinary ideal and Gandhi’s fight to attain it was doubly difficult because the sex drive he was struggling to suppress had been strongly and deeply rooted. For years after taking his vow, Gandhi experimented with different diets, looking for one which would have the slightest possible impact on his sexual organs. While thousands of Indians sought out exotic foods to stimulate their desires, Gandhi spurned in turn spices, green vegetables, certain fruits, in his efforts to stifle his.

Thirty years of discipline, prayer and spiritual exercise were needed before Gandhi reached the point at which he felt he had rooted out all sexual desire from his mind and body. His confidence in his achievement was shattered one night in Bombay in 1936, in what he referred to as ‘my darkest hour’. That night, at the age of 67, thirty years after he’d sworn his Brahmachari’s vow, Gandhi awoke from a dream with what would have been to most men of that age a source of some satisfaction, but was to Gandhi a calamity, an erection. There, quivering between his loins, was proof he had still not reached the ideal towards which he’d been striving for three decades. Gandhi was so overwhelmed by anguish at ‘this frightful experience’, that he swore a vow of total silence for six weeks.

He pondered for months over the meaning of his weakness, debating whether he should retreat into a kind of Himalayan cave of his own making. He finally concluded his horrible nightmare was a challenge to his spiritual force thrown up by the forces of evil. He decided to accept the challenge, to press on to his goal of extirpating the last traces of sexuality from his being.

As his confidence in the mastery of his desires came back, he gradually extended the range of physical contact he allowed himself with women. He nursed them when they were ill and allowed them to nurse him. He took his bath in full view of his fellow ashramites, male and female. He had his daily massage virtually naked, with young girls most frequently serving as his masseuses. He often gave interviews or consulted the leaders of his Congress Party while the girls massaged him. He wore few clothes and urged his disciples, male and female, to do likewise because clothes he said, only encouraged a false sense of modesty. The only time he ever addressed himself directly to Winston Churchill was in reply to his famous phrase ‘half-naked fakir’. He was trying to be both, Gandhi said, because the naked state represented the true innocence for which he was striving. Finally, he decreed that there would be no problem in men and women who were faithful to their vow of chastity sleeping in the same room at night, if they happened, in the performance of their duties, to find themselves together at nightfall.

The decision to have Manu share his pallet so he could guide more totally her spiritual growth was, to Gandhi, a natural outgrowth of that philosophy. During the agonizing days of his penitent’s pilgrimage, her delicate figure was rarely out of his sight. From village to village, she shared the crude shelters offered him by the peasants of Noakhali. She massaged him, prepared his mudbaths, cared for him when he was striken with diarrhoea. She slept and rose with him, prayed by his side, shared the contents of his beggar’s bowl. One bitter February night she awoke to find the old man shaking violently by her side. She massaged him, heaped on his shivering frame whatever scraps of cloth she could find in the hut. Finally, Gandhi dozed off and, she later noted, ‘we slept cosily in each other’s warmth until prayer time’.

For Gandhi, secure in his own conscience, there was nothing improper or even remotely sexual in his relations with Manu. Indeed, it is almost inconceivable that the faintest tremor of sexual arousal passed between them. To the Mahatma, the reasoning which had led him to perform what was, for him, a duty to Manu, was sufficient justification for his action. Perhaps, however, deep in his subconscious, other forces he ignored helped propel him to it.

In the twilight of his life, Gandhi was a lonely man. He had lost his wife and closest friend in wartime prison. He was losing the support of some of his oldest followers. He risked losing the dream he’d pursued for decades. He had never had a daughter and, perhaps, the one failure in his life had been in his role as a father. His eldest son, embittered because he’d felt his father’s devotion to others had deprived him of his share of paternal affection, was a hopeless alcoholic who had staggered drunk to his dying mother’s bedside. Two of his other sons were in South Africa and rarely in contact with Gandhi. Only with his youngest son did he enjoy a normal father-son relation. In any event, whatever the explanation, a deep, spiritual bond was destined to link the Mahatma and the shy, devoted girl so anxious to share his misery during the closing months of his life.

As word of what was happening spread beyond his entourage, a campaign of calumnies, spread by the leaders of the Moslem League, grew up about Gandhi. The news reached Delhi, spreading intense shock among the leaders of Congress waiting to begin their critical talks with India’s new Viceroy.

Gandhi finally confronted the rumours in an evening prayer meeting. Assailing the ‘small talk, whispers and innuendo around him’, he told the crowd that his great-niece Manu shared his bed with him each night and explained why she was there. His words calmed his immediate circle, but when he sent them to his newspaper Harijan to be published, the storm broke again. Two of the editors quit in protest. Its trustees, fearful of a scandal, did something they had never dreamed of doing before. They refused to publish a text written by the Mahatma.

The crisis reached its climax in Haimchar, the last stop on Gandhi’s tour. There, Gandhi revealed his intention to carry his mission to the province of Bihar where, this time, he would work with his fellow Hindus who had killed the members of a Moslem minority in their midst.

His words alarmed the Congress leadership in Delhi who feared the effect his relationship with Manu could have on Bihar’s orthodox Hindu community. A series of emissaries discreetly asked him to abandon it before leaving for Bihar. He refused.

Finally, it was Manu herself, perhaps prodded by one of those emissaries, who gently suggested to the elderly Mahatma that they suspend their practice. She remained absolutely at one with him, she promised. She was renouncing nothing of what they were trying to achieve. The concession she proposed was only temporary, a concession to the smaller minds around them who could not understand the goals he sought. She would stay behind when he left for Bihar. Saddened, Gandhi agreed.

New Delhi, March – April 1947

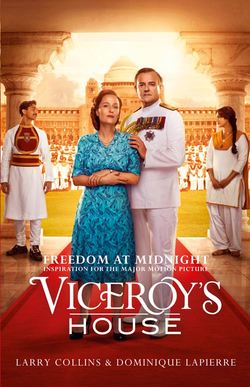

In his immaculate white naval uniform, ‘he looked like a film star’ to the 23-year-old captain of the Grenadier Guards just appointed one of his ADCs. Serene and smiling, his wife at his side, Louis Mountbatten rode up to Viceroy’s House in a gilded landau built half a century before for the royal progress through Delhi of his cousin, George V. At the instant his escort reached the palace’s grand staircase, the bagpipes of the Royal Scots Fusiliers skirled out a plaintive welcome to India’s last Viceroy.

A faint, sad smile on his face, the outgoing Viceroy, Lord Wavell, waited at the head of the staircase. The very presence in New Delhi of those two men represented a break with tradition. Normally, an outgoing Viceroy sailed with due pomp from the Gateway of India while the next steamer bore his successor towards its spans, thus sparing India the embarrassment of having two Gods upon its soil at the same time. Mountbatten himself had insisted on this breach of custom so he could talk with the man to whom he formally bowed his head as he reached the top of the stairs.

For a moment, in the intermittent glare of flashbulbs, the two men stood chatting. They were a poignantly contrasting pair: Mountbatten the glamorous war hero, exuding confidence and vitality; Wavell, the one-eyed old soldier, adored by his subordinates, brusquely sacked by the politicians, a man who had sadly noted in his diary not long before that, for the past half decade, his had been the unhappy fate ‘to conduct withdrawals and mitigate defeats’.*

Wavell escorted Mountbatten through the heavy teak doors to the Viceroy’s study and his first direct confrontation with the awesome problems awaiting him.

‘I am sorry indeed that you’ve been sent out here in my place,’ Wavell began.

‘Well,’ said Mountbatten, somewhat taken aback, ‘that’s being candid. Why? Don’t you think I’m up to it?’

‘No, it’s not that,’ replied Wavell, ‘indeed, I’m very fond of you, but you’ve been given an impossible task. I’ve tried everything I know to solve this problem and I can see no light. There is just no way of dealing with it. Not only have we had absolutely no help from Whitehall, but we’ve now reached a complete impasse here.’

Patiently, Wavell reviewed his efforts to reach a solution. Then he stood up and opened his safe. Locked inside were the only two items he could bequeath his successor. The first sparkled on dark velvet folds inside a wooden box. It was the diamond-encrusted badge of the Grand Master of the Order of the Star of India, the emblem of Mountbatten’s new office, which, forty-eight hours hence, he would hang around his neck for the ceremonial which would officially install him as Viceroy.

The second was a manilla file on which was written the words ‘Operation Madhouse’. It contained the only solution the able soldier had to propose to India’s dilemma. Sadly, he took it out of the safe and laid it on his desk.

‘This is called “Madhouse”,’ he explained, ‘because it is a problem for a madhouse. Alas, I can see no other way out.’

It called for the British evacuation of India, province by province, women and children first, then civilians, then soldiers, a move likely, in Gandhi’s words, to ‘leave India to chaos’.

‘It’s a terrible solution, but it’s the only one I can see,’ Wavell sighed. He picked up the file from his desk and offered it to his stunned successor.

‘I am very, very, very sorry,’ he concluded, ‘but this is all I can bequeath you.’

As the new Viceroy concluded that sad introduction to his new functions, his wife, on the floor above Wavell’s study, was receiving a more piquant introduction to her new life. On reaching their quarters, Edwina Mountbatten had asked a servant for a few scraps for the two sealyhams, Mizzen and Jib, which the Mountbattens had brought out from London. To her amazement, thirty minutes later, a pair of turbaned servants solemnly marched into her bedroom, each bearing a silver tray set with a china plate on which were laid several slices of freshly roasted chicken breast.

Eyes wide with wonder, Edwina contemplated that chicken. She had not seen food like it in the austerity of England for weeks. She glanced at the sealyhams, barking at her feet, then back at the chicken. Her disciplined conscience would not allow her to give pets such nourishment.

‘Give me that,’ she ordered.

Firmly grasping the two plates of chicken, she marched into the bathroom and locked the door. There, the woman who would offer in the next months the hospitality of Viceroy’s House to 25,000 people, gleefully began to devour the chicken intended for her pets.

The closing chapter in a great story was about to begin. In a few minutes on this morning of 24 March 1947, the last Englishman to govern India would mount his gold and crimson viceregal throne. Installed upon that throne, Louis Mountbatten would become the twentieth and final representative of a prestigious dynasty, his would be the last hands to clasp the sceptre that had passed from Hastings to Wellesley, Cornwallis and Curzon.

The site of his official consecration was the ceremonial Durbar Hall of a palace whose awesome dimensions were rivalled only by those of Versailles and the Peterhof of the Tsars. Ponderous, solemn, unabashedly imperial, Viceroy’s House, New Delhi, was the last such palace men would ever build for a single ruler. Indeed, only in India with its famished hordes desperate for work would a palace like Viceroy’s House have been built and maintained in the twentieth century.

Its façades were covered with the red and white stone of Barauli, the building blocks of the Moghuls whose monuments it had succeeded. White, yellow, green, black marble quarried from the veins that had furnished the glistening mosaics of the Taj Mahal, embellished its floors and walls. So long were its corridors that in its basement servants rode from one end of the building to the other on bicycles.

This morning, those servants were giving a last polish to the marble, the woodwork, the brass of its 37 salons and its 340 rooms. Outside, in the formal Moghul gardens, 418 gardeners, more than Louis XIV had employed at Versailles, laboured to provide a perfect trim to its intricate maze of grass squares, rectangular flower beds and vaulted water-ways. 50 of them were boys hired just to scare away the birds. In their stables, the 500 Punjabi horsemen of the Viceroy’s bodyguard adjusted their white and gold tunics as they prepared to mount their superb black horses. Throughout the house, gold and scarlet turbans flaring above their foreheads, their white tunics already embroidered with the new Viceroy’s coat of arms, other servants scurried down the corridors on a final errand. For the last time, they all, gardeners, chamberlains, cooks, stewards, bearers, horsemen, all the retainers of that feudal fortress lost in the twentieth century, joined in preparing the enthronement of one of that select company of men for whom it had been built, a Viceroy of India.

In one of the private chambers of the great house, a man contemplated the white full-dress admiral’s uniform his employer would wear to take possession of Viceroy’s House’s majestic precincts. No flaring turban graced his head. Charles Smith was not a product of the Punjab or Rajasthan, but of a country village in the south of England.

With a meticulous regard for detail acquired over a quarter of a century of service in Mountbatten’s employ, Smith slipped the cornflower-blue silk sash of the world’s most exclusive company, the Order of the Garter, through the right epaulette and stretched it taut across the uniform’s breast. Then he looped the gold aiguillettes which marked the uniform’s owner as a personal ADC to King George VI through the right epaulette.

Finally, Smith took his employer’s medal bar and the four major stars he would wear this morning from their velvet boxes. With respect and care he gave a last polish to their gleaming gold and silver enamel forms: the Order of the Garter, the Order of the Star of India, the Order of the Indian Empire, the Grand Cross of the Victorian Order.

Those rows of ribbons and crosses marking the milestones of Louis Mountbatten’s career were, in their special fashion, the milestones along the course of Charles Smith’s life as well. Since he had joined Mountbatten’s service as third footman at the age of eighteen, Smith had walked in another man’s shadow. In the great country houses of England, in the naval stations of empire, in the capitals of Europe, his employer’s joys had been his, his triumphs, his victories, his sorrows, his griefs. During the war, he had joined the service and eventually followed Mountbatten to South-east Asia. There, from a spectator’s seat in the City Hall of Singapore, Charles Smith had watched with tears of pride filling his eyes as Mountbatten, in another uniform he’d prepared, had effaced the worst humiliation Britain had ever endured by taking the surrender of almost three-quarters of a million Japanese soldiers, sailors and airmen.

Smith stepped back to contemplate his work. No one in the world was more demanding when it came to dressing a uniform than Mountbatten, and this was not a morning to make a mistake. Smith unbuttoned the jacket and sash, and gingerly lifted it from the dress dummy on which it rested. He eased it over his own shoulders and turned to a mirror for a final check. There, for a brief and poignant moment before that mirror, he was out of the shadows. For just a second, Charles Smith, too, could dream he was the Viceroy of India.

Slipping his tunic, heavy with its load of orders and decorations, over his torso, Louis Mountbatten could not help thinking of those magic weeks a quarter of a century earlier when he’d discovered India by the side of his cousin, the Prince of Wales. Both of them had been dazzled by the majestic air surrounding the Viceroy of India as he presided over his empire. So much pomp, so much luxury, such homage seemed to accompany his slightest gesture that the Prince of Wales himself had remarked, ‘I never understood how a king should live until I saw the Viceroy of India.’

Mountbatten remembered his own youthful amazement at the panoply of imperial power that focused on the person of one Englishman the allegiance of the world’s densest masses. He recalled his awe at the manner in which the viceregal establishment had blended the glitter of a European court and the faintly decadent aura of the feasts of the Orient. Now, against his will, that viceregal throne with all its pomp and splendour was about to be his. His Viceroyalty, alas, would bear little resemblance to that gay round of ceremonies and hunting that had stirred his youthful dreamings. His youthful ambitions were to be fulfilled, but in the real world, not the fairy-tale world of 1921.

A knock on the door interrupted his meditation. He turned. The rigorously unemotional Mountbatten started at the sight framed in the doorway of his bedroom. It was his wife, a diamond tiara glittering in her brown hair, her white silk gown clinging to the curves of a figure as slim and supple as it had been that day she had walked out of St Margaret’s, Westminster, on his arm.

Like her husband, Edwina Mountbatten seemed to have been sought out for the blessings of a capricious Providence. She had beauty. She possessed a fine intellect, more penetrating some thought than her husband’s. She had inherited great wealth from her maternal grandfather, Sir Ernest Cassel, and social position from her father’s family whose forebears included England’s great nineteenth-century Prime Minister, Lord Palmerston, and the famous philanthropic politician, the seventh Earl of Shaftesbury. There had been clouds in her paradise. An intensely unhappy childhood after her mother’s early death had left her with an introverted nature. She was easily hurt and kept the pain of those hurts locked inside her where they corroded the linings of her being. Small things pained her. Unlike her ebullient husband who never hesitated to criticize anything that displeased him and accepted criticism with lofty aplomb, Edwina Mountbatten took offence easily. ‘You could tell Lord Mountbatten what you wanted, any way you wanted to,’ recalled one of their senior aides. ‘With Lady Louis, you had to proceed with the utmost care.’

She had locked her shyness, her introverted nature into the strait-jacket of an unyielding will. By that will, she made herself into something which nature had not intended her to be: an outgoing woman, seemingly extroverted. But the price was always there to be paid. She had been speaking in public for a decade, sometimes two or three times a week, yet, before making a major speech, her hands shook almost uncontrollably. Her health was as fragile as a porcelain vase. She suffered almost daily from the cruel thrusts of a migraine headache, but no one outside her family knew, because physical weakness was not something she was prepared to indulge. Unlike her self-confident husband who could boast he ‘never, never worried’, Edwina worried constantly. While he slept immediately and soundly, sleep’s solace came to her only as a pill-induced torpor.

Two distinctly separate periods had marked the Mountbattens’ quarter of a century together. During the first fourteen years of their marriage, while Louis Mountbatten was slowly moving up the naval ladder, he had insisted they exclude her wealth and their social position from the naval environment in which they spent much of their time. Away from the naval stations, however, in London, Paris and on the Riviera, Edwina became, her daughter recalled, ‘the perfect social butterfly’, a zealous party-giver and party-goer, blazing through the twenties with the intensity of a Fitzgerald heroine. When she was not dancing she sought the stimulation of adventure: chartering a copra schooner in the South Pacific, flying on the first flight from Sydney to London, being the first European woman up the Burma Road.

That carefree, innocent period in their life had ended with Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia. By Munich, the transformation was complete. From then on, her life was dominated by the conviction that it was immoral not to be fully occupied by the pursuit of some social or political good. The giddy heiress became a social reformer, the social butterfly a concerned activist with a liberal outlook little appreciated by her peers.

During the war, she led the St John Ambulance Brigade with its 60,000 members. When Japan surrendered, her husband urgently requested her to tour the Japanese prisoner-of-war camps so as to organize the care and evacuation of their most desperate inmates. Before the first soldiers of his command had set foot on the Malayan Peninsula, Edwina Mountbatten, armed only with a letter from her husband, her only escort a secretary, three of her husband’s staff officers and an Indian ADC, plunged into territory still under Japanese control. She continued all the way to Balikpan, Manila and Hong Kong, fearlessly berating the Japanese, forcing them to provide food and medicine for their prisoners until Allied help could arrive. Thousands of starving, wretchedly ill men were saved by her actions.

Like her husband, she ended the war with a chestful of well-earned decorations. Now she was to play at his side a vital role in New Delhi. She would be his first and most trusted confidante, his discreet and private emissary in moments of crisis, his most effective ambassador to the Indian leaders with whom he would have to deal.

Like her husband, she, too, would leave behind in India the imprint of her style and character. A woman of extraordinary versatility, Edwina Mountbatten would be able in an evening to preside over a formal banquet for 100 in a silk evening dress, a diamond tiara glittering in her hair, and, the following morning, in a simple uniform, walk through mud up to her ankles to cradle in her lap the head of a child dying of cholera in the filth of an Indian hovel. She would display in those moments a human compassion some found lacking in her husband. Hers was not the condescending gesture of a great lady perfunctorily acknowledging the misery of the poor, but a heartfelt sorrow for India’s sufferings. The Indians would see the sincerity of Edwina Mountbatten’s feelings and respond in turn to her as they had never responded before to an Englishwoman.

As his wife advanced across the room towards him, Mountbatten could not help thinking what a strange resolution this day was to their destinies. Less than a mile separated the bedroom in which they stood contemplating each other and the spot on which he had asked Edwina Ashley to marry him a quarter of a century before. It was 14 February 1922, and they had been sitting out the fifth dance of a Viceroy’s ball in honour of the Prince of Wales. Their hostess that evening, the Vicereine, Lady Reading, had not been overjoyed at the news. The young Mountbatten, she had written to his new fiancée’s aunt, did not have much of a career before him.

Mountbatten remembered her words now. Unable to suppress a smile, he took his wife’s arm and set out to install her on Lady Reading’s gold and crimson throne.

India was always a land of ceremonial splendour and on that March morning, when Louis Mountbatten was to be made Viceroy, the blend of Victorian pomp and Moghul munificence that had stamped the rites of the Raj was still intact. Spread before the broad staircase leading to the Durbar Hall, the heart of Viceroy’s House, were honour guards from the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force. Sabres glittering in the morning sunlight, Mountbatten’s bodyguard, in scarlet and gold tunics, white breeches and glistening black leather jackboots lined his march to the hall.

Inside, under its white marble dome, the elite of India waited: high court judges, their black robes and curling wigs as British as the law they administered; the Romans of the Raj, senior officers of the Indian Civil Service, the pale purity of their Anglo-Saxon profiles leavened by a smattering of more sombre Indian faces; a delegation of maharajas gleaming like gilded peacocks in their satin and jewels; and, above all, Jawaharlal Nehru and his colleagues in Gandhi’s Congress, their rough homespun cotton khadi harbingers of the onrushing future.

When the first members of Mountbatten’s cortege stepped into the hall, four trumpeters concealed in niches around the base of the dome began a muted fanfare, their notes rising as the procession moved forward. The lights of the great hall, dimmed at first, rose in rhythm to the trumpets’ gathering crescendo. At the instant India’s new Viceroy and Vicereine passed through the great doorway, they blazed to an incandescent glare, and the trumpets sent a triumphant swirl of sound reverberating around the vaulted dome. Solemn and unsmiling, the Mountbattens slow-marched down the carpeted aisles towards their waiting thrones.

A kind of apprehension, a rising tension not unlike that he had once known on the bridge of the Kelly in the uncertain moments before battle, crowded in on Mountbatten. Each gesture measured to the grandeur of the moment, he and his wife moved under the crimson velvet canopy spread over their gilded thrones and turned to face the assembly. The Chief Justice stepped forward and, his right hand raised, Mountbatten solemnly pronounced the oath that made him India’s last Viceroy.

As he pronounced its concluding words, the rumble of the cannon of the Royal Horse Artillery outside rolled through the hall. At that same instant all across the sub-continent, other cannons took up the ponderous 31-gun salute. At Landi Kotal at the head of the Khyber Pass; Fort William in Calcutta where Clive had set Britain on the road to her Indian Empire; the Lucknow Residence where the Union Jack was never struck in honour of the men and women who had defended it in the Mutiny of 1857; Cape Comorin, past whose monazite sands the galleons of Queen Elizabeth I had sailed; Fort St George in Madras where the East India Company had its first land grant inscribed on a plate of gold; in Poona, Peshawar and Simla; everywhere there was a military garrison in India, troops on parade presented arms as the first gun exploded in Delhi. Frontier Force Rifles, the Guides Cavalry, Hodson’s and Skinner’s Horse, Sikhs and Dogras, Jats and Pathans, Gurkhas and Madrassis poised while the cannon thundered out their last tattoo for the British Raj.

As the sound of the last report faded through the dome of Durbar Hall, the new Viceroy stepped to the microphone. The situation he faced was so serious that, against the advice of his staff, Mountbatten had decided to break with tradition by addressing the gathering before him.

‘I am under no illusion about the difficulty of my task,’ he said. ‘I shall need the greatest goodwill of the greatest possible number, and I am asking India today for that goodwill.’

As he finished the guards threw open the massive Assam teak doors of the Hall. Before Mountbatten was the breathtaking vista of Kingsway and its glistening pools, plunging down the heart of New Delhi. Overhead the trumpets sent out another strident call. Suddenly, walking back down the aisle, Mountbatten felt his apprehension slip away. That brief ceremony, he realized, had turned him into one of the most powerful men on earth.

Forty-five minutes later, back in civilian clothes, Mountbatten settled at his desk. As he did, his jamadhar chaprassi, his office footman, walked in in his gold turban bearing a green leather despatch box which he ceremoniously set in front of the Viceroy. Mountbatten opened it and pulled out the document inside. It was a stark confirmation of the power which he had just inherited, the final appeal for mercy of a man condemned to death. Fascinated and horrified, Mountbatten read his way through each detail. The case involved a man who had savagely beaten his wife to death in front of a crowd of witnesses. It had been so thoroughly combed, passed through so many appeals, that there were no extenuating circumstances to be found. Mountbatten hesitated for a long minute. Then, sadly, he took a pen and performed the first official act of his Viceroyalty.

‘There are no grounds for the exercise of the Royal prerogative of mercy,’ he noted on the cover.

Before setting out to impose his ideas on India’s political leaders, Louis Mountbatten sensed he had first to impose his own personality on India. India’s last Viceroy might, as he had glumly predicted at Northolt Airport, come home with a bullet in his back, but he would be a Viceroy unlike any other India had seen. Mountbatten firmly believed, ‘it was impossible to be Viceroy without putting up a great, brilliant show.’ He had been sent to New Delhi to get the British out of India, but he was determined they would go in a shimmer of scarlet and gold, all the old glories of the Raj honed to the highest pitch one last time.

He ordered all the ceremonial trappings suppressed during the war to be restored: ADCs in dazzling full-dress, guard-mounting ceremonies, bands playing, sabres flashing, ‘the lot’. He loved every splendid moment of it, but a far shrewder concern than his own delight in pageantry underlay it.

The pomp and panoply were designed to give him a viceregal aura of glamour and power, to provide him a framework which would give his actions an added dimension. He intended to replace the ‘Operation Madhouse’ of his predecessor by an ‘Operation Seduction’ of his own, a mini-revolution in style directed as much towards India’s masses as the leaders with whom he would have to negotiate. It would be a shrewd blend of contrasting values, of patrician pomp and common touch, of the old spectacles of the dying Raj and new initiatives prefiguring the India of tomorrow.

Strangely, Mountbatten began his revolution with the stroke of a paint brush. To the horror of his aides, he ordered the gloomy wooden panels of the viceregal study in which so many negotiations had failed, to be covered with a light, cheerful coat of paint more apt to relax the Indian leaders with whom he’d be dealing. He shook Viceroy’s House out of the leisurely routine it had developed, turning it into a humming, quasi-military headquarters. He instituted staff meetings, soon known as ‘morning prayers’, as the first official activity of each day.

Mountbatten astonished his new ICS subordinates with the agility of his mind, his capacity to get at the root of a problem and, above all, his almost obsessive capacity for work. He put an end to the parade of chaprassis who traditionally bore the Viceroy his papers for his private contemplation in green leather despatch boxes. He did not propose to waste his time locking and unlocking boxes and penning handwritten notes on the margins of papers in the solemn isolation of his study. He preferred taut, verbal briefings.

‘When you wrote “may I speak?” on a paper he was to read,’ one of his staff recalled, ‘you could be sure you’d speak, and you’d better be ready to say what was on your mind at any time, because the call could come at two o’clock in the morning.’

It was above all the public image Mountbatten was trying to create for himself and his office that represented a radical change. For over a century, the Viceroy of India, locked in the ceremonial splendours of his office, had rivalled the Dalai Lama as the most remote God in Asia’s pantheon. Two unsuccessful assassination attempts had left him enrobed in a cocoon of security, isolating him from all contact with the masses he ruled. Whenever the Viceroy’s white and gold train moved across the vast spaces of India, guards were posted every 100 yards along its route 24 hours in advance of its arrival. Hundreds of bodyguards, police and security men followed each of his moves. If he played golf, the fairways were cleared and police posted along them behind almost every tree. If he went riding, a squadron of the Viceroy’s bodyguard and security police jogged along after him.

Mountbatten was determined to shatter that screen. First, he announced he and his wife or daughter would take their morning rides unescorted. His words sent a wave of horror through the house, and it took him some time to get his way. But he did, and suddenly the Indian villagers along the route of their morning rides began to witness a spectacle so unbelievable as to seem a mirage: the Viceroy and Vicereine of India trotting past them, waving graciously, alone and unprotected.

Then, he and his wife made an even more revolutionary gesture. He did something no Viceroy had deigned to do in two hundred years: visit the home of an Indian who was not one of a handful of privileged princes. To the astonishment of all India, the viceregal couple walked into a garden party at the simple New Delhi residence of Jawaharlal Nehru. While Nehru’s aides looked on dumb with disbelief, Mountbatten took Nehru by the elbow and strolled off among the guests, casually chatting and shaking hands.

The gesture had a stunning impact. Thank God,’ Nehru told his sister that evening, ‘we’ve finally got a human being for a Viceroy and not a stuffed shirt.’

Anxious to demonstrate that a new esteem for the Indian people now reigned in Viceroy’s House, Mountbatten accorded the Indian military, two million of whom had served under him in South-East Asia, a long overdue honour. He had three Indian officers attached to his staff as ADCs. Next, he ordered the doors of Viceroy’s House to be opened to Indians, only a handful of whom had been invited into its precincts before his arrival. He instructed his staff that there were to be no dinner parties in the Viceroy’s House without Indian guests. Not just a few token guests; henceforth, he ordered, at least half the faces around his table were to be Indian.

His wife brought an even more dramatic revolution to the viceregal dining table. Out of respect for the culinary traditions of her Indian guests, she ordered the house’s kitchens to start preparing dishes which, in a century of imperial hospitality, had never been offered in Viceroy’s House, Indian vegetarian food. Not only that, she ordered the food to be served on flat Indian trays and servants with the traditional wash basins, jugs and towels to stand behind her guests so they could, if they chose, eat with their fingers at the Viceroy’s table, then wash their throats with a ritual gargle.

That barrage of gestures large and small, the evident and genuine affection the Mountbattens displayed for the country in which their own love affair had had its beginnings, the knowledge that the new Viceroy was a deliverer and not a conqueror, the respect of the men who’d served under him in Asia; all combined to produce a remarkable aura about the couple.

Not long after their arrival the New York Times noted, ‘no Viceroy in history has so completely won the confidence, respect and liking of the Indian people.’ Indeed, within a few weeks, the success of ‘Operation Seduction’ would be so remarkable that Nehru himself would tell the new Viceroy only half jokingly that he was becoming a difficult man to negotiate with, because he was ‘drawing larger crowds than anybody in India’.

The words were so terrifying that Louis Mountbatten at first did not believe them. They made even the dramatic sketch of the Indian scene Clement Attlee had painted him on New Year’s Day seem like a description of some tranquil countryside. Yet the man uttering them in the privacy of his study had a reputation for brilliance and an understanding of India unsurpassed in the viceregal establishment. A triple blue and a first at Oxford, George Abell had been the most intimate collaborator of Mountbatten’s predecessor.

India, he told Mountbatten with stark simplicity, was heading for a civil war. Only by finding the rapidest of resolutions to her problems was he going to save her. The great administrative machine governing India was collapsing. The shortage of British officers caused by the decision to stop recruiting during the war and the rising antagonism between its Hindu and Moslem members, meant that the rule of that vaunted institution, the Indian Civil Service, could not survive the year. The time for discussion and debate was past. Speed, not deliberation, was needed to avoid a catastrophe.

Coming from a man of Abell’s stature, those words gave the new Viceroy a dismal shock. Yet they were only the first in a stream of reports which engulfed him during his first fortnight in India. He received an equally grim analysis from the man he’d picked to come with him as his Chief of Staff, General Lord Ismay, Winston Churchill’s Chief of Staff from 1940 to 1945. A veteran of the sub-continent as officer in the Indian Army and military secretary to an earlier Viceroy, Ismay concluded, ‘India was a ship on fire in mid-ocean with ammunition in her hold.’ The question, he told Mountbatten, was: could they get the fire out before it reached the ammunition?

The first report Mountbatten received from the British Governor of the Punjab warned him ‘there is a civil war atmosphere throughout the province’. One insignificant paragraph of that report offered a startling illustration of the accuracy of the Governor’s words. It mentioned a recent tragedy in a rural district near Rawalpindi. A Moslem’s water buffalo had wandered on to the property of his Sikh neighbour. When its owner sought to reclaim it, a fight, then a riot, erupted. Two hours later, a hundred human beings lay in the surrounding fields, hacked to death with scythes and knives because of the vagrant humours of a water buffalo.

Five days after the new Viceroy’s arrival incidents between Hindus and Moslems took 99 lives in Calcutta. Two days later, a similar conflict broke out in Bombay leaving 41 mutilated bodies on its pavements.

Confronted by these outbursts of violence, Mountbatten called India’s senior police officer to his study and asked if the police were capable of maintaining law and order in India.

‘No, Your Excellency,’ was the reply, ‘we cannot.’ Shaken, Mountbatten put the same question to Field-Marshal Sir Claude Auchinleck, Commander-in-Chief of the Indian Army. He got the same answer.

Mountbatten quickly discovered that the government with which he was supposed to govern India, a coalition of the Congress Party and the Moslem League put together with enormous effort by his predecessor, was in fact an assembly of enemies so bitterly divided that its members barely spoke to one another. It was clearly going to fall apart, and when it did, Mountbatten would have to assume the appalling responsibility of exercising direct rule himself with the administrative machine required for the task collapsing underneath him.

Confronted by that grim prospect, assailed on every side by reports of violence, by the warnings of his most seasoned advisers, Mountbatten reached what was perhaps the most important decision he would make in his first ten days in India. It was to condition every other decision of his Viceroyalty. The date of June 1948 established in London for the Transfer of Power, the date he himself had urged on Attlee, had been wildly optimistic. Whatever solution he was to reach for India’s future, he was going to have to reach it in weeks, not months.

‘The scene here,’ he wrote in his first report to the Attlee government on 2 April 1947, ‘is one of unrelieved gloom … I can see little ground on which to build any agreed solution for the future of India.’

After describing the country’s unsettled state, the young admiral issued an anguished warning to the man who had sent him to India. ‘The only conclusion I have been able to come to,’ he wrote, ‘is that unless I act quickly, I will find the beginnings of a civil war on my hands.’

* The impulses thrusting Gandhi to take his vow were not Hindu alone. As Christ’s dictum of turning the other cheek had been vital in helping him formulate his non-violent ideal, so Jesus’ words referring to ‘those who become eunuchs for my sake … for love of the Kingdom of Heaven’, had inspired him in taking his ancient Hindu pledge.

* The Attlee government had treated Wavell in particularly brutal fashion. He had been in London when Mountbatten was asked to replace him, but given no hint he was about to be sacked. He learned the news only hours before Attlee made it public. It was only on Mountbatten’s insistence that Attlee accorded him the elevation in his rank in the peerage which traditionally was offered a departing Viceroy.