Читать книгу Freedom at Midnight: Inspiration for the major motion picture Viceroy’s House - Dominique Lapierre, Larry Collins - Страница 8

PREFACE

ОглавлениеIn each passing century there are a few defining moments of which it can truly be said: ‘Here history was made’ or ‘Here mankind’s passage through the ages took a new direction or turned towards a new horizon.’ Such a moment occurred on the morning of 28 June 1914 when Gavrilo Princip stepped from the crowds in Sarajevo to assassinate Archduke Franz Ferdinand and set Europe on the road to the slaughterhouse of the First World War, or again on that winter day in 1942 in Chicago when Enrico Fermi ushered in the Atomic Age with the first nuclear chain reaction.

Of equal importance in the history of our fading century was yet another moment, this one just seconds after the midnight of 14–15 August 1947 when the Union Jack, emblazoned with the Star of India, began its final journey down the flagstaff of Viceroy’s House, New Delhi. For the last retreat of that proud banner proclaimed far more than just the end of the British Raj and the independence of 400 million people, at the time one-fifth of the population of the globe. It also heralded the approaching end of the Age of Imperialism, of those four and a half centuries of history during which the white, Christian heirs of Europe held most of the planet in their thrall. A new world was coming into being that night, the world that will go with us across the threshold of the next millennium, a world of awakening continents and peoples, of new and often conflicting dreams and aspirations.

High drama it was, and what a cast of characters stood centre stage that night! Admiral of the Fleet Lord Louis Mountbatten, Earl of Burma, the last Viceroy, sent out to Delhi to yield up the finest creation of the British Empire, proclaimed in the name of his great-grandmother Queen Victoria. Jawaharlal Nehru, a man of impeccable taste, breeding and fastidious intelligence, destined to become the first leader of the tumultuous Third World. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, cool, austere, polite to a fault, but determined to force on the departing British the formation of a new Islamic nation – while savouring nightly the forbidden pleasures of a whisky and soda.

And, towering above the others, Mohandas Karamchand ‘Mahatma’ (Great Soul) Gandhi, the frail prophet of nonviolence who had hastened the end of the empire on which the sun was never to set by the simple expedient of turning the other cheek. In an age when television did not exist, radios were rare and most of his countrymen were illiterate, he proved a master of communications because he had a genius for the simple gesture that spoke to his countrymen’s souls. Surely, as historians and editors begin to choose their candidates for Man or Woman of the Century, his will be a name high on their lists.

Looming as the backdrop to that dramatic moment was the contrast between two Indias. First, the India of the imperial legend dying that night, of Bengal Lancers and silk-robed maharajas, tiger hunts and green polo maidans, royal elephants caparisoned in gold, haughty memsahibs and bright young officers of the Indian Civil Service donning their dinner jackets to dine in solitary splendour in tents in the midst of a steaming jungle. Then there was the new India coming into formal existence with the approaching dawn, a nation often beset by famine and frustration, struggling towards modernity and industrial power through the burden of her multiplicity of peoples, cultures, tongues and religions.

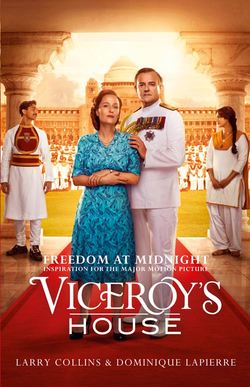

Those were the attractions and challenges which determined us to write Freedom at Midnight. The publication of the book’s original edition in 1975 was blessed by a phenomenon particularly gratifying to authors – enormous popular success accompanied by wide critical acclaim. It inspired, according to screenwriter John Briley, much of his Academy Award-winning script for Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi. A bestseller in Europe, the United States and Latin America, the book’s most significant impact was, understandably, on the Indian sub-continent. It was translated into every Indian dialect in which books are published, an accolade once reserved for authors such as Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo. It further received the flattering, if illegal, compliment of imitation in the form of at least 34 pirated editions. In Pakistan, however, an embarrassed government banned the book. Why? We mentioned the indisputable, human failing of the Islamic nation’s founder – he was not averse to eating a slice of bacon with his morning eggs.

In reviewing our original text for this new fiftieth anniversary edition, we found little that we felt demanded revision or rewriting. We did, however, feel that in view of the half-century which has passed since the events described in the book and the years since its initial publication, there were some parts of the story which merited an updating. To do that, we returned to our thirty hours of tape-recorded interviews with Lord Mountbatten and the other original sources which underlie the book.

As India and Pakistan mark the fiftieth anniversary of their independence, the antagonism which has governed their relationship for half a century continues unabated. Both countries now possess nuclear weapons and have threatened to employ them if menaced, making the sub-continent one of the most potentially dangerous regions on earth. Each nation regularly accuses the other of fomenting terrorism on its territory, India seeing the hand of Pakistan behind the guerrilla movement in Kashmir, and Pakistan accusing India of being behind the recent urban violence in Karachi and parts of the Punjab.

At the heart of the dispute between them is, of course, the intractable problem of the lovely Vale of Kashmir, whose overwhelmingly Moslem population lives under increasingly repressive Indian rule. The United Nations has called repeatedly for a plebiscite on the area’s future, a referendum which would almost certainly result in an overwhelming majority for either independence or union with Pakistan. What makes the problem so intractable, however, is the near-certainty that any Indian government which would even contemplate either of those possibilities would risk unleashing violence by Hindu militants on India’s Moslem minority, violence that would probably far exceed anything Kashmir has witnessed to date.

Lord Mountbatten is blamed by most Pakistanis for Kashmir’s post-independence decision to join the dominion of India rather than Pakistan. The accusation is, in fact, both unfair and untrue. On the contrary, Mountbatten probably came closer than anyone has since to effecting a peaceful solution to the problem. With considerable difficulty, he extracted from India’s political leaders Vallabhbhai Patel and Jawaharlal Nehru a pledge to accept a decision by Kashmir’s Hindu Maharaja Hari Singh to join his state to Pakistan. (Under the terms governing the transfer of power, the rulers of India’s princely states were to accede to the dominion either of India or of Pakistan, taking into account the desires of the majority of their populations.)

Armed with that agreement, Mountbatten flew to Srinagar shortly before 15 August, determined to convince Singh to join his state to Pakistan. He urged that course of action on the Maharaja while driving in his station-wagon for a day’s trout fishing in the Trika River.

‘Hari Singh,’ he told the prince, ‘you’ve got to listen to me. I have come up here with the full authority of the government of the future dominion of India to tell you that if you decide to accede to Pakistan because the majority of your population is Moslem, they will understand and support you.’

Singh refused. He told Mountbatten he wanted to become the head of an independent nation. The Viceroy, who considered Singh ‘a bloody fool’, replied: ‘You just can’t be independent. You are a landlocked country. You’re oversized and underpopulated. Your attitude is bound to lead to strife between India and Pakistan. You’re going to have two countries at daggers drawn for your neighbours. You’ll end up becoming a battlefield, that’s what will happen. You’ll lose your throne and your life, too, if you’re not careful.’

Singh persisted, however. He refused to meet officially with Mountbatten again during the Viceroy’s visit. Independence Day came and went and still Hari Singh vacillated, making no official decision on Kashmir’s future. When tribesmen organized and armed by Pakistan descended on his capital, Srinagar, later that autumn, Singh sent out an SOS for help to New Delhi. At that point, it is true, Mountbatten, now Governor-General of the new Dominion of India, told Nehru that he could not legally order Indian troops into Kashmir unless the Maharaja signed a formal act acceding to India. An emissary was dispatched to Srinagar with an act of accession. Singh signed it in great haste and Indian troops were airlifted to Kashmir. They are still there today, and the problem born that autumn day continues to poison relations between the two nations.

Many readers of Freedom at Midnight noted that we did not mention in its pages the oft-cited rumours of a love affair between Lady Edwina Mountbatten and Jawaharlal Nehru. Our decision not to invoke those rumours was deliberate. While there is absolutely no doubt that a special bond of affection united Nehru and Lady Mountbatten, there was no evidence then nor is there any now that their relationship was anything other than platonic. Nehru’s own sister, Mme V.L. Pandit, volunteered to us in a conversation that had no bearing whatsoever on the Nehru – Edwina relationship that her brother had become sexually impotent towards the end of his marriage. That condition, she said, caused the end of the marriage and plagued Nehru for the rest of his life. Given the premium then put on masculine sexuality in Indian society, we found it very difficult to imagine that a sister would lie about such a matter involving a beloved brother. Furthermore, the valet who cared for Nehru’s official bungalow during two visits Lady Mountbatten paid to India’s Prime Minister after independence swore he had seen no evidence whatsoever that the couple had shared a bedroom.

Mountbatten did volunteer that he discussed with his wife the secrets of his continuing negotiations with India’s leaders and that, on occasion, he used her as a vehicle to pass information informally to Nehru which he could not transmit to him officially.

In the years which followed the publication of Freedom at Midnight we, the authors, were on occasion accused of being pro-Mountbatten in its pages. To that charge we plead guilty. In general, there were two major criticisms levelled at the last Viceroy: that he moved too fast in handing over power to India and Pakistan in August 1947, and that he did not do enough to prevent the terrible slaughters which followed that event.

No one, of course, will ever know how many people died in those awful weeks. Mountbatten preferred to use the figure 250,000 dead, an estimate undoubtedly tinged with some wishful thinking. Most historians of the period place the figure at half a million. Some put it as high as two million.

Whatever that tragic toll, with one exception no one in authority in India at the time foresaw a calamity of such magnitude. In the course of our work, we read all the weekly reports submitted to the Viceroy by the governors of India’s provinces. Those officials, men like Sir Evan Jenkins in the Punjab and Sir Olaf Caroe in the North West Frontier Province, represented the best and wisest products of British rule in India, the mandarins of the Indian Civil Service. They were advising a man whose Indian experience was counted in months, not years. Yet none of their reports foresaw a wave of violence even remotely comparable to that which followed Partition.

India and Pakistan’s political leaders – Nehru, Patel, Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan – urged Mountbatten with one voice to transfer power to their hands just as swiftly as possible. Those men had been agitating and preparing for the exercise of power for years. Nothing was going to delay them in getting their hands on that power. Whatever their innermost thoughts may have been, all of them minimized in their recorded conversations with Mountbatten the dangers of the coming Partition of India and vastly overstated their abilities to deal with any troubles which might break out. Only one voice foresaw the dimensions of the tragedy which was about to overwhelm the sub-continent. That was Gandhi’s, and no one in mid-summer 1947 was listening to the prophet of non-violence.

‘What went wrong’, Mountbatten admitted to us, ‘was this sheer, simultaneous reaction which nobody foresaw. No one predicted millions of people would pull up stakes and change sides. No one.’

What, we asked him, would he have done differently had some authoritative voice made such a prediction?

‘I wouldn’t have done anything differently’ was his reply. ‘I couldn’t have. I would have got the leaders together and said: “We’re faced with this problem. What are we going to do?” I could have told them “We won’t transfer power” but that they would never have accepted.’

Some suggest with the benefit of hindsight that Mountbatten, acting in concert with the leaders of the two new dominions, should have held up the publication of Sir Cyril Radcliffe’s boundary awards. That, they argue, would have fixed those migrating millions into place, at least temporarily. Perhaps. Or would the uncertainty have fuelled the already explosive situation and led to even more violence?

There was one vital piece of knowledge denied to Mountbatten in the summer of 1947 which we uncovered during our work. This was the fact that Jinnah was dying of TB and had been told by his doctors with whom we spoke that he had less than six months to live. Had he known that, Mountbatten acknowledged, he would very probably have acted quite differently in India. Jinnah was the one overwhelming roadblock in his attempts to keep India united. Knowing Jinnah was dying, Mountbatten would have been sorely tempted, he admitted, to await his death. Then, perhaps, an independent Pakistan would never have come into being.

As far as the accusation is concerned that he moved too fast, that he rushed India and Pakistan into independence, it must be remembered that a swift transfer of power was part of the brief Mountbatten was given by Clement Attlee when he was appointed Viceroy in January 1947. Both men knew that British power in India had become by that time a hollow shell. The proud Indian Civil Service had been allowed to run down during the war. The soldiers of England’s conscript army in India were no more anxious to die to keep India British than Russian conscripts have been to die to keep Chechnya Russian. Mountbatten was haunted by the spectre of Direct Action Day staged in Calcutta in July 1946 by the Moslem League in which 26,000 Hindus were killed in 72 hours. Another challenge to British authority like that would have exposed just how weak England’s power structure had become in 1947. Mountbatten’s first concern, therefore, was to see that the responsibility for administering and policing India was transferred to Indian hands as quickly as possible. It was a nationalistically determined ordering of his priorities, but it was also the one assigned to him by the men who sent him to India.

One phrase in Chapter 13, entitled ‘Our People Have Gone Mad’, incensed a great number of our Indian readers and merits, perhaps, some comment from us here. It was Lord Mountbatten’s description of Nehru’s and Patel’s appearance when he met them in the study of his residence on Saturday 6 September 1947 on his return from Simla when the worst of the post-Partition violence was shaking India. The two leaders, he said, ‘looked like a pair of chastened school-boys’.

One can certainly say that, at the very least, his was an insensitive turn of phrase. The fact is, however, that Mountbatten did employ exactly those words in talking to us on tape. A week later in a subsequent interview he employed a similar phrase to describe the scene. The two men ‘were like schoolboys, absolutely pole-axed. They didn’t know what had hit them.’

The last Viceroy read the manuscript of Freedom at Midnight before its publication and made no reference to that phrase. Nor did he ask us to remove it following so many criticisms of its use by Indian readers. Was it up to us as the authors to censor his words, however injudicious they might have seemed? We thought not at the time of the book’s first publication and we feel the same way in regard to this new edition.

In the years which followed the original publication of Freedom at Midnight, both of us remained close to Lord Mountbatten. He took great delight in the book’s success, offering copies to Her Majesty the Queen, Prince Charles, for whom he had a special affection, and Prime Minister Harold Wilson, insisting each put aside other concerns to turn their attention to the text.

Mountbatten’s personal archives at his Broadlands Estate contained in well-organized, fireproof cabinets virtually every piece of paper bearing on his life, from the invitation cards to his christening to the menu of the last state dinner he had attended. He intended to use those archives as the foundation upon which some future author might construct his biography, sharing its royalty earnings with his grandchildren. In the years we worked together, he scoffed at the notion of designating his biographer. To do so, he said, would be like consigning himself to the grave. To our surprise, then, he announced to us about a year before his death in that mock imperious tone he sometimes employed, ‘I have decided that it is you two who will write my biography.’

‘Lord Louis,’ we protested, ‘you are one of the century’s most important Englishmen. This country’s establishment would consider it almost an act of treason on your part to entrust your biography to an American and a Frenchman.’

Mountbatten harrumphed, declaring our reply revealed how little either of us understood about the English establishment, an institution for which he, in any event, had a very limited regard. A few months later he returned to the topic. His son-in-law, Lord John Brabourne, the trustee of his archives, agreed, he told us, with our judgement. Relieved, we suggested he might want to consider Hugh Thomas, then the Regius Professor of History at Oxford, but it was clear his thinking on the question was veering back towards his earlier sentiments. Mountbatten died without having settled the question. The task of selecting his official biographer fell, therefore, to his son-in-law, who chose Philip Ziegler, the editor of Freedom at Midnight, for the task.

Although few people were aware of it, Mountbatten suffered from a series of minor cardio-vascular problems in the closing years of his life. His daughters and his doctor urged him to lighten his schedule and temper his zest for work. Rarely has well-intended advice fallen on deafer ears.

On occasion in our chats in those years in his Kinnerton Street flat in London, the conversation would turn to the subject of death. Gandhi’s death in particular fascinated him because, he maintained, the Mahatma had achieved in death what he had been striving to achieve in life, an end to India’s communal violence. That gave a dimension and meaning to his death which destiny accords to few humans. Without ever saying so explicitly, he implied that such an end was one he devoutly wished for, one which he would consider a fitting final chapter to his life.

In August 1979, he prepared, as he did every summer, to spend a family holiday at his castle, Classiebawn, in Ireland. The day before he left he spoke on the phone to one of the authors of this book.

‘Be careful up there, Lord Louis,’ the author warned, ‘you’re an awfully tempting target for those whackos of the IRA.’

‘My dear Larry,’ came the reply, ‘once again you’re revealing how little you know of these matters. The Irish are well aware of my feelings on the Irish question. I am in no danger over there whatsoever.’

A fortnight later, together with the mother of his son-in-law Lord John Brabourne and a young child, he was murdered by an IRA assassin’s bomb hidden in his motor launch as he was setting out to sea for a morning sail.

He would have had nothing but utter contempt for people who would murder an elderly woman and a child. But himself? He died swiftly, afloat upon those endless seas which had played such an important role in his own and his father’s life. Had his death brought some small measure of wisdom to the Republicans and Loyalists killing and murdering in Northern Ireland, might he not have considered it a worthwhile final act, one not incomparable with the death of the man he so admired, Mahatma Gandhi?

Often during our work on Freedom at Midnight he had declared, ‘How can we here in the West possibly blame Hindus and Moslems for killing each other in India when in Northern Ireland we see people of the same basic stock, people who worship the same Resurrected Saviour, slaughtering each other?’

Alas, almost two decades after his death, his sacrifice and that of all the others which have followed it have not succeeded in implanting among the peoples of Northern Ireland a semblance of the wisdom Gandhi’s death bequeathed to his countrymen and women.

LARRY COLLINS

DOMINIQUE LAPIERRE

December 1996