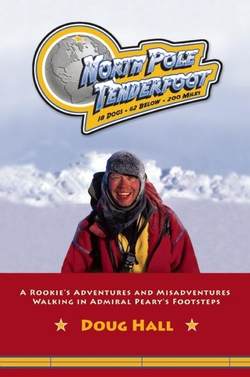

Читать книгу North Pole Tenderfoot - Doug Hall - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Why Are You Going to the North Pole?

“WHY ARE YOU GOING TO THE NORTH POLE?”

It was the most common question from family and friends when I announced my plans to join a dogsled expedition to the North Pole.

It was a fair question, as the North and South poles are some of the most inaccessible and unpleasant places on the planet.

Apsley Cherry-Garrad, in his book The Worst Journey in the World, detailing the Scott expedition to the South Pole, described polar trips this way:

Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time that has yet been devised.

The plan involved traveling about two hundred miles to recreate Admiral Robert E. Peary’s “last dash” to the pole, from 88 degrees to 90 North.

The temperatures, with wind chill, ranged from minus 15 to minus 62 degrees Fahrenheit despite the endless sunlight of spring in the Arctic.

People thought I was crazy. Traveling to the North Pole is not an endeavor a person with complete possession of his marbles would undertake.

To risk understatement: It’s not a popular trip. At the time of our adventure in 1999, only thirty-four people had made the journey by dogsled, as Admiral Peary did. Contrast this with Mount Everest, where more than two thousand people have reached the summit.

Admiral Robert Peary, the North Pole iron man.

If there were a travel brochure for the trip, it would read like this:

On This Trip You’ll Enjoy: Minus 60 Degree Cold,

Blinding Whiteouts, Bouts of Diarrhea.

Frostbite Is a Certainty,

Loss of Fingers and Toes a Real Possibility.

Sounds grim. But at least it’s more optimistic than the ad Ernest Shackleton supposedly ran in London to find crew members for his South Pole expedition:

Men wanted for hazardous journey. Small wages.

Bitter cold. Long months of complete darkness.

Constant danger. Safe return doubtful.

Honour and recognition in case of success.

The question of why are you going to the North Pole can be asked in two ways:

Why are you going

to the NORTH POLE?

In this case the emphasis was placed on why the North Pole. The place itself. However, it was most often asked with emphasis placed on the front of the question, with the emphasis on me:

Why are YOU going

to the North Pole?

For some reason, my family and friends didn’t see me as a great explorer.

Maybe it was my robust profile.

Maybe it was my passion for gourmet cooking.

Maybe it was my habit of exercising my mouth more than my body.

When asked why, my first answer was that I was going to use the expedition to raise money and awareness for my Great Aspirations! charity. Great Aspirations! provides ideas to help parents inspire their children. I’d created the charity based on the work of Dr. Russ Quaglia, director of the National Center for Student Aspirations, located at my alma mater, the University of Maine.

My idea was to use the trip as a publicity tool for raising money from corporate sponsors and to provide a media event to connect parents and children to the Web site, where they could get free educational materials. The www.Aspirations.com Web site provides a free one-hour audio workshop as well as eighty newspaper columns filled with ideas for helping parents inspire their children’s aspirations.

Helping the charity was not a very effective answer to the question. Friends would respond, “Aren’t there less extreme ways to raise money and awareness for the charity?”

For a month or so I brushed off the question with the common answer “Because it’s there.”

Then I did a little research and found the source of that statement. It was first said by British mountaineer George Leigh Mallory in a March 1923 interview in the New York Times when asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest. I stopped saying it when I learned that the primary reason the quote is so famous is because Mallory was lost on Everest the following year. He died! Not the sort of inspiration I needed.

In 1999, the same year I went to the pole, Mallory’s body was found on Everest with his fellow climber, Andrew Irvine. The media debated if Mallory was “going down” or “up” at the time of his death. If he were “going down” then that would mean that he achieved the summit twenty-nine years before Edmund Hillary. Mallory’s son John didn’t see it as a debate. As he said, “To me the only way you achieve a summit is to come back alive. The job is half done if you don’t get down again.”

I’m with John Mallory—coming back alive is key to a truly successful adventure.

When pushed deeper on “why,” I had plenty of flip responses but few honest answers.

If the discussion was taking place over a nip or two of the only alcohol to be named after a country (Scotch whisky), I would wax philosophically about the neglected spirit of adventure in today’s high-tech souls. I would invoke the cosmic karmic nature of the pole—the place where all time zones and all people blend into one. I might even blab eloquently about the spiritual symbolism of standing on top of the world.

These responses rarely worked to answer the question.

Sometimes I would talk of how this trip would allow me to recapture my neglected physical nature. As a youth I earned the rank of Eagle Scout, participated in winter survival training, and spent summers leading canoe trips at Camp Carpenter Boy Scout Camp.

Then, as a teenager, I broke my hip in a pickup football game. It was a freak accident. The doctors at Boston Children’s Medical Hospital gave me a 5 percent chance of walking again.

The skill of my physician, Dr. Trott, some prayers, and some luck, had me walking and running again two years later. In the process my focus moved from the great outdoors to entrepreneurship.

I developed a passion for magic and juggling and created my own show. The excitement of creating, selling, and performing set off a chain reaction of entrepreneurial adventures. I soon had a line of learn-to-juggle kits and magic tricks.

I took to the stage as Merwyn the Magician.

My entrepreneurial ventures helped me land a marketing job in the brand management department of Procter & Gamble in Cincinnati, Ohio. After ten years I retired from P&G to fulfill my entrepreneurial destiny.

With my basement as my office and two rounds of venture financing from some of the biggest names in new business investment (Visa and MasterCard), I connected with some great people to build the Eureka! Ranch, an innovation research and development company.

The North Pole expedition would give me the ability to recapture my lost interest in the great outdoors. At midlife I had the luxury of going back for a moment and exploring the path of high-adventure expeditions. I could restore my sense of sport and adventure, and I could challenge my physical self.

Friends had sympathy for my story, but it didn’t convince them of why I was going to such extremes. More often than not, they would nod in agreement and secretly think I was bonkers.

My wife, Debbie, had a simpler answer to the question. “He’s turning forty,” she would say, triggering expressions of sympathy, as if to say, “Oh, I see.”

I protested. It’s a mere coincidence that I was born in 1959 and that this trip happened to be in 1999 (and that this book is coming out in 2009!).

I mean, come on, I wasn’t in denial of my aging—or at least not in more denial than every other baby boomer. At least I hadn’t done any of the “hair things.” I didn’t color the gray or comb it over to make it look like I had more. I hadn’t done hair implants or bought a “rug,” or had my chest hair lasered or stripped off. “I am what I am,” as Popeye said.

In 1909 Admiral Peary succeeded where 578 other expeditions failed.

Frankly, a big part of my inspiration for going to the North Pole was a six-foot Naval Officer from the Great State of Maine—Admiral Robert E. Peary.

Unlike the instant heroes of pop culture, Admiral Peary is the real thing. For twenty-three years, he dedicated himself to a single goal: standing on the top of the world. When he was not on an expedition he spent most of his time raising money and preparing for the next journey.

His wife called his compulsion “Arctic Fever.”

He succeeded where some 578 expeditions before him had failed. His success was driven by persistence and a dedication that is especially inspiring when compared to today’s need for instant gratification, with short-term business success, and our general lack of sustained dedication to grand and great causes.

I believe the admiral ranks as the greatest all-around explorer in American history. Apologies to Lewis and Clark, but they didn’t travel in conditions that were nearly so extreme. Apologies, too, to John Glenn, Neil Armstrong, and all the other great astronauts who had the brilliant support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

Peary did it all. He raised the money, designed the equipment, selected the team, and led the expedition. He was a one-man NASA complex.

My focus on Peary is based on my respect and emotional awe of the man. Plus, I just plain like the guy.

I’m not saying he was perfect. He had his faults like all of us.

However, when I add up the balance sheet of his assets and liabilities I come out on his side. I believe he’s a rich source of wisdom and inspiration that deserves a deeper look and understanding than he has received up till now.

When it came to inspiration, there may be no grander figure than Admiral Robert E. Peary. The admiral “rocked” when it came to THINKING BIG! In a commencement address at Rensselaer Polytechnic on June 14, 1911, he described his dreams this way:

I have dreamed my dream; and working incessantly with all my strength, have done what it is given to few men to accomplish fully. The determination to reach the pole has been so much a part of my being that, paradoxical as it may seem, I have long ago ceased to think of myself save as an instrument for the attainment of that object. An inventor can understand this, or an artist, or anyone else who works for an idea.

Sadly, five days before Admiral Peary announced his achievement of the pole, his former assistant, Fredrick Cook, announced that he had been to the North Pole the year before. The result was a frenzy of questions and scrutiny that continues to this day. Who was first? Who lied? Who told the truth?

The explorers were supported by competing newspapers, the New York Times (Peary) and the New York Herald (Cook), which fanned the flame of controversy.

Having been to the pole by dogsled, I can’t see how Cook could have traveled the distance he claimed with the supplies he claimed to have taken. Most Arctic enthusiasts have reached the same conclusion.

Some feel that Peary chose to take Matthew Henson (above) with him to the pole instead of Captain Bob Bartlett because he had something to hide.

Admiral Peary’s place in history is still not certain. Three mysteries hang over Peary’s expedition, and part of my goal in recreating his “last dash” was to find answers to those questions.

1. Why was he so silent upon his return to the ship? After returning to the ship, he was very quiet and did not talk to anyone about what happened on the “last dash” from 88 degrees to the pole. It’s been speculated that he had something to hide.

2. Why did he take Henson instead of Bartlett to the pole? The decision to take Henson, a black man, instead of Bartlett, a white man, sparked great controversy in the racist world of the time. Matthew Henson was Peary’s most experienced expedition aide. Bartlett was his most trusted friend and confidant on the expedition. Peary naysayers feel that his decision proves Peary had something to hide.

3. Did he actually make it to the pole in 1909? The fundamental question: Is there evidence “beyond a reasonable doubt” that Admiral Peary, Matthew Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah actually reached the North Pole on April 6, 1909?

Responses to other Peary controversies, such as his sled speeds from 88 degrees to the pole and his method of navigation, have been addressed by others in the hundred years since Peary’s expedition.

Finding answers to these questions about my hero made up a big part of the answer to the question people asked about why I was going to the pole. And, okay, turning forty may have played a role in it too. But even before I left I knew at some level that I didn’t really know the answer to the question. Though all my answers were true, they didn’t quite add up to the full answer. Before I could truly understand why I was going to the North Pole, I would have to go.