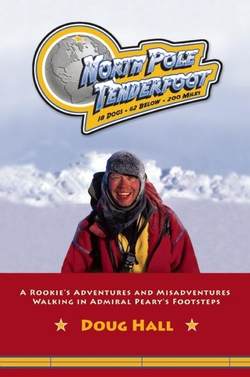

Читать книгу North Pole Tenderfoot - Doug Hall - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 2

The Adventure Begins

DECEMBER 1998

AS AN EXPLORATION ROOKIE, my first challenge was to prove that I had the “right stuff” at an Arctic try out at Paul and Sue Schurke’s Wintergreen Dogsled Lodge in Ely, Minnesota. It involved a week of training, spiced with a handful of oddball challenges created by our expedition leader, the world’s leading authority on high-Arctic travel, Paul Schurke.

The purpose of our week in training was to see if the candidates—one woman and eight men, including myself—would “make the cut” for the expedition, although the real test would be whether we each could write a $20,000 check to pay for the privilege of freezing our fingers, toes, and noses. It was here that I would meet the other candidates. It was here, too, that we would bond as a team and determine our roles.

Craig Kurz, fellow tenderfoot on the expedition

My friend Craig Kurz agreed to join me. Craig, who was thirty-seven, was the perfect companion for a wilderness expedition—a dynamo with unlimited energy. A natural leader, a go-to kind of guy, Craig has never known a favor he can’t do for another. He is the CEO of The HoneyBaked Ham Company in northern Kentucky, a five-time world champion equestrian, a runner, scuba diver, white-water rafter, and a cross-country and downhill skier.

On the pole trip, Craig was a rookie like me. He’d done a few trips at Paul’s lodge but nothing to compare to the high adventure of a real Arctic expedition.

We agreed to provide each other with the inspiration or motivation necessary to make the trip a success.

“We might need to give each other a kick in the butt sometimes,” Craig said. “There won’t be time for feeling hurt or letting personal feelings get in the way.”

As we traveled to Minnesota, we also agreed that we felt privileged to be part of a trip of this magnitude. From what we’d read about our teammates in the e-mails prior to this “try out” trip, we were in over our heads. We would be stepping into a brave new world.

Our plane landed in Hibbing, Minnesota, the birthplace of the bus industry in the United States. It started in 1914 when miners were transported to and from the Iron Range towns and developed into the Greyhound bus company, a story told through exhibits and memorabilia at the Greyhound Museum. Sadly, our timing didn’t allow a visit to this local landmark.

For a small town, Hibbing has a healthy share of famous sons, from folk singer Bob Dylan to sports stars Roger Marris and Kevin McCale to Vincent Bugliosi, the prosecutor in the Charles Manson case who later became an acclaimed author. More relevant to my taste buds, it’s also the home of food entrepreneur Jeno Paulucci, creator of over eighty food brands, including Jeno’s Pizza Rolls, Chun King, and RJR foods.

From Hibbing we pointed our rental car north to Ely, population 3,968. Ely is literally the end of the road. Its primary fame is as the leaping off point for summer canoe camping trips into the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, which has over a million acres of wilderness and waterways. It’s famous for spectacular views and black flies. Fortunately, we visited during the off season so there was no need for bug spray.

Not to be outdone by Hibbing, Ely has its own famous sites, including the Native American Heritage Center, which celebrates the life and ways of the Bois Forte Band of Ojibwe. Visitors also can see the International Wolf Center, a multimillion-dollar complex dedicated to wolves. The independent spirit of Ely also comes to life at the Dorothy Molter Museum. Known as the Root Beer Lady, Dorothy’s cabins were a famous stop-over point for canoeists who would come for a sip of her homemade root beer. Dorothy was the last resident of the Boundary Waters. After she died in 1986, her two cabins were transported out of the Boundary Waters and made into a museum.

Foregoing all of these points of interest, we headed to Paul Schurke’s lodge, where we parked the car with the windshield wipers flipped up to keep them from freezing to the windshield. The winter sun cast dim rays over White Iron Lake as we walked the gravel road from the parking lot to the lodge. Along the way, I thought about my first visit here a few years earlier. I’d signed up for a lodge-to-lodge “comfort class” trip, with dogsledding during the day followed by a hot shower, a gourmet meal, and a warm bed. At night in the comfort of the lodges, Paul showed video from his Arctic trips. On one of those nights I caught Arctic Fever, burning up with the idea that I could and should be part of one of those trips.

Paul Schurke

Paul Schurke was a large part of the reason my wife, Debbie, was confident I would return safely from my polar adventure. In a world of ten-minute heroes, Paul is the genuine article. He’s been featured in cover stories in National Geographic magazine and various television specials. Outside magazine has named him “person of the year” and Backpacker magazine named him the king of cool for his passion for winter camping.

He’s led four dogsled adventures to the North Pole—three of which were successful. His landmark 1986 journey, which included adventurer Will Steger, was the first surface trek to the pole without resupply since Admiral Peary in 1909.

In 1989 he led the Bering Bridge expedition, a twelve-hundred-mile dogsled and ski trek with a twelve-member Soviet-American team, from Siberia to Alaska via the Bering Strait to reestablish cultural connections among Arctic natives long separated by the Cold War.

Paul’s excursions depart from most so-called adventure trips, where clients fork over big bucks to have Sherpas schlep their gear up mountaintops and provide whatever is needed. With Paul, I paid handsomely to be a grunt bearing the brunt of the load. I figured that after I got over the pain, the trip would provide massive bragging rights in the world of macho exploration.

If the North Pole has a PR man, Paul is it. In an interview for our Expedition Web site, Paul was clear about his preferences for the North Pole versus the other two major adventures—Antarctica and Everest.

“Trekking to the top of the world represents one of the world’s greatest geographic challenges,” he said. “Of course, the bigger the challenge, the bigger the rewards, and I’ve always considered my polar successes to be a marvelous gift. They’re a resource I draw on each time I tackle other personal or business goals. The North Pole puts all other challenges in perspective and, for me, has made many other dreams achievable.

“A South Pole trek is obscenely expensive—upwards of one hundred thousand dollars per person. It’s also boring. The South Pole sits amid an absolutely featureless expanse of ice. And it’s anticlimactic. You arrive there to find a research station staffed by hundreds.

“An Everest climb is nearly as expensive and insanely dangerous. One of eight climbers is injured or killed. Besides, climbing Everest has been accomplished by a whole lot more people than the North Pole.”

As we entered the lodge, I felt confident about my abilities. Over the previous few months, I’d exercised like crazy, working overtime to make myself as fit as possible for the expedition. I had also read numerous books about the world of Arctic explorers with particular emphasis on the admiral.

But over the course of the next few hours, as I met my fellow North Pole adventurers, my confidence melted away.

The first prospective teammate I met was David Golibersuch, Ph.D. He said he was a Hivernaut.

“A what?” I asked.

“Hivernaut,” David said, pronouncing it EE-ver-not. “Paul coined it. ‘Hiver’ is French for ‘winter’ and ‘naut’ is Greek for ‘explorer.’”

David Golibersuch

I nodded, peering at him to determine if he was joking. He wasn’t. He was serious.

David was fifty-six, a native of Buffalo, New York, unmarried with two daughters. Since 1970 he’d worked in corporate research and development for General Electric in Schenectady, New York. An experienced cross-country skier, he made his first journey to the high Arctic in the spring of 1998, on a Schurke-led excursion to Ellesmere Island.

Mike Warren

Next, I met Mike Warren, fifty-one, a real estate developer in Gainesville, Florida. He had climbed Mt. Rainier and trekked to Kala Patar in Nepal. He told stories of climbing the Rainier, becoming intimate with the sight of the heel of the person in front of him so he could step in his footstep.

I asked him what he expected from the trip to the pole.

“I do not—repeat, do not—expect it to be fun,” he replied. “You do trips like this for the physical, mental, and spiritual challenge. It’s absolutely grueling, but there’s tremendous satisfaction when you complete the journey. And there’s great camaraderie when a group of people come together and combine their talents to achieve a goal.”

On and on it went. Each team member was more macho than the last. Each was a veteran of pain and punishment. I was a veteran of meetings and memos.

I introduced myself to Bill Martin, the co-leader of the trip, a lanky guy of forty-nine with a big smile. A resident of Gainesville, Florida, he had led climbing expeditions in North and South America, Russia, the Himalayas, and Antarctica.

Bill wondered if I was related to Rob Hall, who had been a good friend of his.

“Had been?” I asked.

Bill explained that Rob was the guide whose death on Everest was made famous by Jon Krakauer’s book Into Thin Air. “Rob was a major dreamer who lived the dreams that others merely dream,” Bill said.

Thinking I might find an answer to the eternal question, I asked, “Why do you do it?”

“Because I’m brain damaged,” Bill explained with a proud smile. “I spend six weeks a year on adventures. I’m an orthodontist. I arrange my practice so that I can train and make trips like this.”

“So what’s it really like on a trip like this?” I asked, a thinly veiled attempt to understand what I had gotten myself into.

Bill quickly became analytical: “When I climbed in Antarctica I learned that first you’re freezing—colder than you’ve ever been before. Then, as time goes on, you acclimate, your body adapts—assuming, of course, you’re in good enough shape to handle the trip.”

Good enough shape?

I wondered what was good enough shape. Again, I consult this Jedi Master: “What’s good enough shape?”

“I run up and down the stairs of the local university’s football stadium,” Bill said, “wearing a full pack.”

He paused to let me explain my training regimen. Figuring that my daily two-mile run wasn’t macho enough, I did the only thing I could think of—I took a long slug of Scotch.

Gulp!

I was in trouble. What had I been thinking?

Sensing my anxiety, Bill suddenly shifted from macho mountain man to mentor. He assured me I would be okay. “Listen close and train hard, harder than you can imagine, and you’ll be fine.”

I took a deep breath, and made a mental note to keep close to Bill during this Hell week. He could be my guide to the world of high adventure.

The rest of the expedition team included:

• Celia Martin, Bill’s forty-five-year-old sister, also from Gainesville, also an orthodontist. Our teeth would be straight for this trip. An alumnus of Outward Bound wilderness courses, Celia was an avid hiker. I would learn that she’s quick to speak her mind. When I messed up, she was blunt about saying so, but she conveyed the message with a gentleness that made me feel okay about my incompetence.

Celia Martin

• Alan Humphries, thirty-six, from County Down in Northern Ireland, near Belfast. Alan was an entrepreneur with a chain of small casinos in and around Northern Ireland. Next to Paul, Alan was our most experienced musher, having dogsledded across Hudson Bay in 1996 and piloted an eight-day team in the 1997 World Dogsledding Championships, a time-trial sprint race covering twenty-five kilometers a day over three days in Finland.

Alan Humphries

He said he had dreamed of going to the North Pole since childhood. “I remember getting a gift as a child, a little guy known as Action Man who came with a polar exploring expedition kit, complete with dogs and sleds and the whole works. I’ve had the bug since then.”

• Randy Swanson, forty-two, was from Grandville, Michigan, where he owned an auto repair business. He had climbed Africa’s Mt. Cameroon and Mt. Bartle-Frere in Australia. Like Alan, he was also an alumnus of one of Paul’s Arctic trips.

Randy Swanson

I asked Randy what drew him to this kind of trip.

“I love the physical rigors,” he said. “I like it when the going gets tough. That’s when I shine.”

Gulp. Who were these people?

An accomplished guitarist with tastes ranging from classical to alternative, Randy said he found it difficult to explain to friends why he wanted to go to the North Pole.

“Nobody understands,” he said. “They all think I’m going to Alaska. Or they wonder if I’m going to stay overnight in lodges. Or they want to know if there’s a certain path I’ll be following. Most people don’t have any idea what this trip will be like.”

• Corky Peterson was from Minneapolis, where he had been the Hennepin County data processing director until his retirement. On the trip up to Wintergreen, Craig and I were most impressed (or intimidated) by Corky’s bio. We wondered what kind of guy at sixty-nine would sign on for a trip like this.

He clearly was no ordinary person. He had an intensity of focus and sense of priority unlike any of the rest of us.

Corky Peterson

“I went on a wilderness trip to Ellesmere Island last year and thought everyone would be about my age,” he said. “I was shocked to find they were mostly twenty years younger. People thought, ‘Oh, how wonderful it was that someone my age would undertake such an endeavor.’ I thought, ‘Hey, what’s the problem?’”

On our trip, Corky stood to become the oldest person to ever reach the North Pole by foot.

“But I hope I can do something worthwhile with the Aspirations! Expedition for people my age,” he said. “Maybe within my church and with others in my age group, maybe I can be an encouragement for us to get off our duffs, to stop letting people tell us we can’t do this or that.”

Like Alan, Corky has dreamed of going to the North Pole since he was a boy.

“I used to stare at the globe in school and wonder what was underneath that spindle at both ends. I want to be where time has no meaning, where all the longitudes come together. The pole is within reach, and now I have the time to do this,” he said.

“What do you think of the risk?” I asked. “What scares you?”

“I’ve read a lot about previous polar teams. Falling through the ice is a challenge, keeping up physically is a challenge. But I haven’t read anything that seems too difficult. Whatever happens, I’ll handle it.”

I knew I was in big trouble. Even Grandpa Corky had more of the “right stuff” than I had.

He was calm and ready. I was nervous and uncertain.

• Paul Pfau, Los Angeles County Assistant Attorney. Paul was the last to join the expedition. He’d helped run base camps on Mount Everest for numerous expeditions. He was very calm and focused. I took the calm as the sign of a real expert.

Paul Pfau

That night, Paul Schurke called us together to talk about the week ahead and about the trip to the North Pole. “You’ll be training at the lodge for a day or two, then we’ll head out on a camping trip with dogs, sleds, and skis. At the end of the week Bill and I will meet with each of you to discuss your suitability for the expedition, your role on the trip, and what you have to do to be more prepared.”

Then he asked for our questions. Craig, never timid about plunging forward, broke the ice with the most obvious one.

How cold will it be in the Arctic?

“Hopefully, very cold,” Paul said. “I’m hoping for minus 30, which will keep the ice fairly firm. As conditions warm, the ice breaks up and makes it a lot tougher to reach the pole. During my ‘95 trip, we had to make a dash to the pole because the ice was breaking up. And on my last trip in ‘97, we didn’t make it because of open water.”

I suddenly realized that reaching the pole was not a given. Even if I overcame my lack of physical fitness, even if I overcame my fear, circumstances beyond our control could prevent me from standing on top of the earth. It was not a happy moment.

More questions followed rapid fire. Paul’s answers were direct and honest. He should never run for public office.

How far will we be going?

“We’ll start about 130 miles from the pole as the crow flies. But since we can’t fly like a crow, we’ll end up walking two hundred miles when you add 25 percent for detours and three to four miles a day for the southerly ice drift. Remember, we’ll be traveling on a sheet of ice that historically floats south as we travel north.”

This is the portion of Peary’s trip known as the “last dash.” It was here that Peary decided to send back Captain Bob Bartlett, a white man, and to take Matthew Henson, a black man, with him to the pole. In 1909 a black man was not considered a reliable witness. Peary’s choice of Henson was made for many reasons, as I’ll explain later. However, to many who still harbored deep prejudices it was clear evidence that Peary had something to hide.

How dangerous is it?

“Safety will be our paramount consideration. But I do not consider a North Pole expedition to be a life-threatening or even a significantly dangerous endeavor. To my knowledge, only one casualty has resulted from North Pole expeditions in this century and that was a member of Peary’s support team who was allegedly bumped off by a couple of severely disgruntled teammates. None of our treks from 88 to the pole have resulted in injuries. The only significant situations we’ve had to deal with were a few unexpected dips in the drink. In each case, team members were dried off, warmed up, and back on track within an hour or two.”

How many dogs will we take?

“I’m guessing eighteen—two teams of nine each.”

How many people will we have on the team?

Looking around the room he said, “This is it. It looks like we’ll have eleven.”

As Paul talked I did some quick math. Although this trip is extreme, it is nothing compared to the admiral’s 1909 trip. We will be traveling from 88 degrees. He started from land, which is at 83.7 degrees, traveling over three times farther. We will be flown up to 88 degrees, then travel on foot to the pole where planes pick us up.

What if someone gets hurt?

“We’ll have to handle it on the ice. We’ll be sixteen-hundred miles north of Alaska. It can take as long as a week before a plane can get to us.”

A week? Jeez.

How do we get there?

“We’ll meet in Edmonton, Canada, then fly to Resolute, a small Inuit town well inside the Arctic Circle. From there, we’ll take Twin Otter planes to 88 degrees. We’ll stop along the way at the Eureka weather station and possibly at a fuel cache that’s been set up on the ice. If all goes well, we’ll be flown back from the pole a couple weeks later.”

What’s the biggest danger?

“Water. Not enough and too much. You can easily get dehydrated because the air in the Arctic is very dry and we’ll be sweating a lot. We’ll make water by melting snow. But while we need to stay hydrated, it’s important to get the water out of our systems. As you sweat, the water needs to be wicked away from your body. If it seals in, you’ll freeze when you stop moving. Water transfers your body heat twenty-five times faster than air.”

What about polar bears?

“Polar bears are known to travel the polar realm, but none have been sighted on our North Pole treks and the few I’ve seen elsewhere in the Arctic are always in a hasty retreat. They’re notoriously shy of dog teams. Of course there’s not much risk, as long as you’re not the slowest runner.”

As Paul chuckled at his little joke, I looked at the folks around me and sized up their running skills. I decided I would in no way be fastest, but I’d probably be two up from the slowest.

“There’s actually little risk,” Paul continued. “The dogs’ barking tends to keep bears away. On the ice, only eighteen deaths from polar bears have ever been reported.”

At first I felt comforted by such a low number, but then considered the ridiculously low number of humans who ever go on the polar ice. The probability of dying from a bear attack was considerably higher than dying in a traffic accident less than ten miles from your home. As Paul talked for a few minutes about bears, I imagined trying to fight off two of them—an eight-hundred-pound female and an eleven-hundred-pound male. Then I imagined myself being eaten.

What about falling into the ocean?

David Golibersuch was quick with an answer based on his statistical analysis of past Arctic treks: “Roughly one in four people who travel to the far north go for a swim.”

A shiver shimmied up my spine. Craig’s face showed the same fear. I did the math: eleven people on the trip meant that Craig and I would probably both go for a swim. Or, I’d go swimming two or three times.

Paul sensed our apprehension. He said, “Don’t worry. At the end of this week we’ll all go for an icy swim. You’ll learn what it’s like and how to get out.”

I looked for a sign that he was kidding. He offered none. I asked if he’d ever fallen in.

“Nope,” he said with a big, unabashed grin.

So how would he know what it’s like to fall in at 30 below with no lodge nearby offering warmth and dry clothes?

The topic chilled the conversation. Bill jumped in with a positive spin, talking about why this trip excited him. He said it was the first expedition he’d been on with a mission that went beyond personal achievement. He talked about how this level of expedition was about man against nature; about how all the great challenges had been faced; about how the only option was to add another level of craziness—to be the first to climb a mountain without a jacket, without oxygen, aboard a pogo stick, or on a unicycle.

Paul then asked me to discuss the Great Aspirations! charity. He had told me previously, that in order to use the trip as a publicity tool for my charity, I’d need to get the approval of the team. I explained to the group that during the fall of 1997, I came across an article about Dr. Russ Quaglia, Director of the National Center for Student Aspirations at the University of Maine, my alma mater. After fifteen years of research, Dr. Quaglia had developed a set of principles on how to build student aspirations. Russ’s primary work was with schools.

After meeting him I proposed the creation of a charity that would translate and publish his work to parents. The result was a nonprofit charity called Great Aspirations! The charity’s purpose was to create and publish ideas that could help parents help their kids. We accomplished this through a national newspaper column distributed by Universal Press Syndicate and through the free distribution of audiotapes and CDs to parents.

I explained that the program came from a no-whining-allowed perspective. It was based on a commonsense approach and principles that really work. I went on to explain some of the data behind the program:

Working with at-risk fourth and fifth graders, kids whose previous academic performances were far below average, we were able to affect an overall increase in these kids’ grades by some 50 percent and an increase of 80 percent of their grades by a full letter grade. On average, their national test scores increased some 150 percent. Discipline problems virtually disappeared, and all said they were actually excited about learning.

A separate field study with a group of Cincinnati third graders found that discipline problems declined 72 percent, absentees declined 25 percent, and tardiness declined 54 percent. Moreover, report card evaluations showed an increase in all the standard measures of “good student citizenship.” Once the Aspiration principles were put into place, our test group demonstrated better self-control, more cooperation with others, respect and consideration for others, and the ability to follow directions. At the same time, their ability to focus on tasks doubled. And some 81 percent of these students get strong ratings in terms of completing all their assignments.

By this point in my presentation I seemed to be getting interest, but I wasn’t sure. So I went for the jugular. I reviewed research my team had conducted with Johnson & Johnson that found a near one-to-one relationship between a child’s self-image and that of his parents. That means that, for every parent with a low self-image, there’s at least one child with an equally low self-image. If they even try, are they as likely to try their best? Or are they going to be conditioned to failing? Will they see opportunity as something to seize or shy away from? It’s a bleak picture.

And there’s more. While reviewing research about childhood growth, we made another discovery. There’s a high correlation between a child’s grades in the third grade and the eleventh grade. That means that by the time kids are eight years old, they’ve developed an academic pattern that is likely to carry throughout their school years, unless something comes along to change it. It’s a structure that rigidly defines who’s smart and who’s dumb, who falls into the neat little slots of “A” students, “D” students, and so on. That means by the age of eight, most of us have it set in our minds where we fall on that letter grade scale.

After clarifying the urgency of the issue, I explained how our expedition fit with the four Great Aspirations! principles.

Belonging: For an expedition to be successful it’s critical to develop a sense of teamwork, community, and belonging. Paul Schurke is a master at taking groups of strangers and crafting them into a team. Equally important is that each team member’s individual strengths, weaknesses, and personality be recognized, appreciated, and integrated into the whole.

Excitement: The feeling of going to places few have seen fuels the heart and soul of each team member with the spirit of true adventure. A trip to the North Pole sparks fun, excitement, curiosity, and creativity.

Accomplishment: A feeling of optimism, overt goal setting, and healthy risk taking fuels a feeling of accomplishment. Each day we face good and bad situations. By working together as a team, we can achieve what none of us could do by ourselves.

Leadership: Paul Schurke is the trip leader. His unique blend of knowledge, skill, common sense, and quiet confidence inspires people to do what they would never consider doing. For this expedition to be successful, each member of the team will need to develop and exhibit his or her own leadership.

My proposition was to use our North Pole expedition as a publicity stunt to gain awareness of the free educational materials at the www.aspirations.com Web site. The vision was to use the North Pole, the land of Santa, to engage children and parents to come together through our journey.

The trip became the Great Aspirations! Expedition.

To make this happen, I would ask my Eureka! Ranch clients for sponsorships to fund a national public relations effort for the trip and to fund further publishing and support of organizations that help ignite the Great Aspirations! principles.

To build awareness of the expedition, we’d use the Great Aspirations! newspaper column, and my colleague and friend David Wecker, our base camp commander, would post stories about our expedition on the Scripps Howard newswire.

On the trip, we planned to use the then-new Iridium satellite network of phones and text pagers to communicate. I would call David each night, and he would write a story, which would be published as “North Pole Telegram” each night on the Web site. Family, friends, and children around the world could send each of us text messages on our individual pagers. In addition, each day a special family activity or “Great Event” (as I called them) would be posted for children and parents to do together.

Finally, syndicated cartoonist Tom Wilson was sending his loveable little cartoon character Ziggy and his dog Fuzz on the trip with us to serve as our official “spokes characters.” Having Ziggy on the trip enhanced the appeal to families worldwide. In addition, via his globally syndicated cartoon strip, Ziggy would alert his seventy-five million readers of the Aspirations expedition.

After my explanation, Paul asked for the team’s perspective on the charity.

I was surprised that support was universal.

Bill said, “The charitable cause gives the expedition a sense of real purpose.”

In retrospect, I shouldn’t have been surprised. The Great Aspirations! charity and the world of genuine adventurers are kindred spirits. Each believes in dreaming big and reaching for grand goals.

The team’s support was even more impressive because they gained nothing from it financially. All of the sponsorship money went directly to the charity.

It’s interesting to note that Admiral Peary’s 1909 journey had a similarly higher mission. President Theodore Roosevelt wrote to Peary, “I feel that you are doing most admirable work for science, but I feel even more that you are doing admirable work for America and are setting an example to the young men of our day which we need to have set amid the softening tendencies of our time.”

The meeting ended, but the conversation continued, with the adventure veterans sharing their tales of victory and hardship. Though their stories fascinated me, I felt a distance from the group. Their “club” intimidated me, even as it drew my interest. I wondered if, at reaching the North Pole, I’d be a member.

Theodore Roosevelt saw Admiral Peary off. Peary’s ship was named the Roosevelt in the president’s honor.

Just after midnight, I went to my room and unrolled my new Wiggies sleeping bag on top of a Hudson Bay red-and-black striped blanket. I would sleep in the bag I’d take to the pole. I even opened the window a crack, thinking it might help me acclimate.

I felt good. The bag was puffy. I felt like I was inside a cloud. Then my feet hit the bottom of the bag. I could barely move in its embrace, but I slept well. The next morning, I was rested and ready.

I volunteered to help feed the dogs before breakfast. It was 7:00 A.M. as I bundled up in my new gear, pulled on my new boots, and headed to where Craig and a few others were already wrestling with the dogs. As I stepped on the outside porch the thermometer read 10 degrees above, which was mild by Arctic standards.

Entering the kennel area—a honeycomb of wooden boxes, plywood dividers, and wire fencing—I took off my mittens to free my hands to help with the dogs. Within a couple minutes, my fingers went from feeling chilled to feeling frozen to feeling numb.

I shook them to try to bring back feeling, and when that failed I quietly freaked out. Not just because of my numb fingers but because I suddenly came face to face with the stark, undeniable realization that I was in over my head. Absolutely, indisputably waaaaaay over my head. If I was freezing at 10 degrees, what would I do in the minus-30 neighborhood?

A barrage of anxieties shot off in my mind. I’m a pretender, an imposter trying to pull off a colossal charade. What will my sponsors, my children, my friends say? How would I explain to them that, hey, sorry, but I found out in the nick of time that it would be far too cold in the Arctic.

I laughed at the thought. Then I laughed at myself. “Look, dummy,” I said to myself, “of course, it’s going to be cold. What did you expect? Get over it.”

My fear calmed a bit. For the mo-ment.

After breakfast, we all took a brisk hike through the woods. The pace was aggressive. Schurke’s long deer-like legs flew through the pucker brush while I struggled to find footing on the mossy rocks. With each step, my feet slipped to one side or the other. Against those blessed with long legs, I’ve always been at a disadvantage. My legs are an inch and a half shorter than they should be, due to the football accident that broke the growth plate in my left hip. To keep my legs an even length, so that I wouldn’t have a lifelong limp, my doctors halted the growth of my right leg.

I began to see that perspiration really is the enemy more than the cold. Sweat poured down my back like a salty Niagara. Schurke advised us to open our jackets and to vent away the heat our bodies generated.

As I struggled along, I glanced now and then at my companions. Was I totally out of synch with the situation? They looked so calm. Or perhaps they were hiding their fear better than I was. Some of them were even laughing.

For the next two days, Paul and Bill filled our heads with information. When we weren’t on the trail, immersing ourselves as much as possible in the ways of Arctic camping, we watched videos of Paul’s previous trips.

Then we embarked into the North Woods. It was the first time that year that Paul’s dogs had been out for a run, and they were eager to pull. Chains ran the length of the sled runners to slow down the dogs, but the runners might as well have been greased with butter.

There wasn’t much snow, so we went onto the lake. The dogs galloped at a speed fast enough, almost, for my life to flash before my eyes. We completed several long runs with the dogs and spent a couple nights in the woods with Paul’s staffers as our babysitters. Then we went out on our own for two nights.

The dogs were rested and ready for adventure.

Craig and I became the cooks for the expedition. I don’t know exactly how it happened. We may have gotten kitchen duty because we had the least experience. Or it could have been the only job we felt confident we could handle. I do consider eating one of my talents.

On the trail I found myself comparing myself to my teammates, sizing them up while sizing up myself.

I felt the same way when I worked out at Mercy Healthplex to get in shape for the trip. I’d lift one plate where others had lifted four, five, or six. It was embarrassing to set the weights lower than the guy—or the gal or the senior citizen—who had gone before me.

As my status as a high-adventure rookie became clearer to me, my fear of being exposed continued to grow. My work in the corporate world had not prepared me for this situation. Pushing the mind to find new ideas is not at all like pushing the body to its breaking—or freezing—point.

On the training trip the two rookies, Craig and Doug, got the cooking duties.

But as my spirits hit bottom, my sense of humor rescued me. My exaggerated fears struck me as comical. I found myself laughing. Watching me laugh at myself and mumble to myself, my teammates must have been ready to have me committed. Somewhere out in the woods, I surrendered to the idea that I would survive the Arctic or I would not, but in any case, I was going.

Early one morning, we awoke to Paul hollering that the ice was cracking and we had thirty minutes to break camp. I knew it was a drill; I also knew the issue was real. I’d read of it in Admiral Peary’s book The North Pole.

My frantic scramble to pull myself together could have been an audition for the Keystone Cops. I couldn’t find my glasses, couldn’t find my mittens, my boots were frozen, where were those danged glasses? It took me twelve minutes to get dressed. Paul hollered out to note each minute’s passing. Somehow, thirty-two minutes later, we were off and rolling—two sleds and eight dogs—with all our gear packed and tied down on the sleds.

In that one clumsy moment, the team came together. It was a great feeling, knowing we could work together and make things happen.

During the week I also learned how to navigate celestially. Each of us took a turn with the sextant, learning how to shoot the sun and the noon meridian. The experience reaffirmed my appreciation for modern technology, but it also made me appreciate how things were done before batteries and how the old ways invariably required one to use more of one’s own resources. Paul Schurke’s emphasis on self-reliance appealed to me. Slowly, almost without realizing it, I began to grow into an adventure mindset.

And just as readily, I would relapse into fear and confusion. Later that evening, I put the Why query to Paul, hoping to find an answer that explained why I was drawn to this challenge. Why was this little voice inside me urging, prodding, poking me to go to the North Pole?

Paul’s answer didn’t help, but it was a good one nonetheless. He told me that, growing up, he always wanted to be an astronaut, and the high Arctic was as close as he’d ever get to standing on another planet.

“When the plane leaves, you have this feeling of being dropped onto another planet,” he said. “It’s a powerful sensation. The sound and colors are amazing. The surface and environment change hourly. There is also something about the sense of total isolation from the rest of the earth. It brings your attention to things like never before.”

He paused to collect his thoughts before adding, “Then again, maybe it is just crazy. Maybe we’re just doing an incredibly grueling trek on a constantly moving surface hoping to arrive at an invisible target.”

That night around the campfire, Paul ratcheted up the risk factor. He made us understand what we were about to undertake. He said he was obliged to advise each of us to get a membership in MEDJET, an insurance group that would evacuate us in case of emergency. He also made it abundantly clear that we would have no guides, Sherpas, or friendly polar bears to help us when our loads became heavy. He told us we were the expedition.

By the end of the week I was functioning nicely in nine-degree weather. It wasn’t bad at all. I was struck by how quickly my body adapted to the cold.

Ready, Set, Go — and I was off…

When we returned to the lodge we unhitched and fed the dogs. Then, before we went into the lodge, Paul led us down to the lake for our final test: A full swim in full gear. We were to extricate ourselves on our own and make our way back to the lodge. Seeing myself as the runt of the litter, I was one of the first to volunteer.

Paul pointed to a black hole in the ice. “The ice isn’t too hard,” he said. “Just be sure to hold onto your ski poles. You use the points as ice picks to pull yourself out.”

Then Paul gave the command: “Ready, Set, Go!” I reflexively dug my poles into the ice, thrusting myself forward on my cross-country skis. My legs shook, partly from the cold, partly from absolute terror.

As I reached the edge of the black water, I heaved myself upward, imagining myself in an arching trajectory like one of those Olympic ski jumpers I’d seen on TV, flying gloriously into the wind, almost tasting the thrill of victory.

My first attempt was not successful.

In my mind, it played out in slow motion. Up, up, up I went—a noble Icarus of the ice. What, ho! Was I getting a smidgen of lift from the wind? Down, down, down I went, anticipating the bone-deep chill when I hit the water.

Instead, I bounced.

I bounced.

Instead of a deep hole in the ice, I’d fallen into an eight-inch puddle.

As water rolled down my back, I got super-cold.

The second time I went for a full swim.

Like the rag-dog ski jumper in the famous credits of ABC’s Wide World of Sports, I instantly knew the agony of defeat. The wind seemed to amplify the laughter of my teammates. As I lay there, sprawled out in a freezing cold made colder by the wind, Paul decided I wasn’t sufficiently submerged and casually pointed to another hole.

The wind whipping my wet clothing—coupled with my desire to put this behind me as quickly as possible—inspired me to get moving again. I skied toward another black hole and this time I went straight in, all the way under. The cold grabbed my body like a giant fist and squeezed. I broke the surface and shifted my grip on my ski poles, holding them near the point. Then I used them as ice picks to pull my soaking self back onto the ice.

Paul grinned slightly, then turned his attention to his next victim. As I scrambled the half-mile to the lodge, I mumbled to myself. Actually, I started holding a conversation with a little cartoon devil enemy of mine who loves to make me uncertain, unsure, and downright scared. The devil screamed into the wind,

“HEY IDIOT! What’s the point? You could be warming your balding head on a beach in the Bahamas. Instead, you’re in the middle of a Minnesota winter volunteering to be miserable. Volunteering! And if that’s not dumb enough, you’re going to pay twenty grand for the right to do this.”

“It’s not that bad, it could be worse. At least there’s a lodge to warm up in.”

“There’s a lodge here in Minnesota, but what about in the Arctic? What are you going to do if you fall in up there? Get out! Get out now!”

As I sprinted down the ice toward Paul’s lodge, teeth clacking spastically, I wrestled with another dilemma. When I ran fast with my arms swinging, the wind chill was frigid. If I walked slowly, I could wrap my arms around myself and feel warmer but it took longer. Should I run or walk? I opted for running, hoping that the numbness I was feeling on my face, fingers, and toes would not do permanent damage.

To ignore the devil, I focused on what the admiral wrote about tenderfeet and how they handled a “wetting.”

It was with a feeling of intense satisfaction that I watched, my Arctic ‘tenderfeet,’ as I called them, proving the mettle of which they were made. A man who cannot laugh at a wetting or take as a matter of course a dangerous passage over moving ice, is not a man for a serious Arctic expedition.

The devil saw an opening and pushed hard at my fragile confidence, “Be honest. You are not a man for a serious Arctic expedition.”

I tried hard to convince myself that I could do it. I told myself that a touch of lunacy, mixed with levity, is a prerequisite for trekking to the North Pole. As with any great adventure, it’s not the rational thing to do. The whole idea of this trip is to see what I’m made of.

The admiral said it himself:

The Arctic is a great test of character. One may know a man better after a short time there than after a lifetime of acquaintance in cities. There is something in those frozen spaces that brings a man face to face with himself and with his companions. If he is a man, the man comes out. If he is a cur, the cur shows as quickly.

The devil worked this hard:”Well I guess we know the answer to the question ‘Are you a man?’”

Before I could respond, I arrived at the lodge. I peeled off my ice-crusted clothes and rubbed my fingers to bring warmth back into the tips. I poured myself a healthy nip of Scotch but I avoided adding ice or a splash of cold water. I’d had enough of that for one day.

I knew that alcohol actually makes you colder, but the trip was finished and I felt I’d earned it. Besides, the admiral liked a nip of brandy. He carried a bottle with him on his Arctic expeditions. He wrote of how the brandy would freeze solid at minus 60.

As the rest of the team made their way into the lodge, I looked at Paul’s pictures from the Arctic hanging in the lodge.

The expedition will take us over white ice, blue ice, and ice of all textures and degrees of hardness. It will be, essentially, flat and monotonous. In my romanticized notion of the North Pole, I pretended I would know I’d arrived when I saw the red-and-white striped barber’s pole.

The reality, of course, is that there is no barber pole at the North Pole. It’s actually an imaginary place that can only be located with navigational tools. And, since the Arctic is nothing but floating ice, the spot on the ice that is mathematically the North Pole is moving constantly. You could pitch a tent at the pole one day and be four miles away from the pole the next without ever leaving the tent.

I knew the trek to the pole would require agonizing exertion, interspersed with moments of holy terror from open water, numb fingers, and polar bear tracks that would remind us we weren’t necessarily at the top of the food chain. As I sat down beside Paul’s woodstove sipping my second glass of fine Scotch, I still didn’t know why I was about to put myself through this harrowing ordeal. I just knew it was something I had to do.

The next morning, Paul and Bill summoned us one by one to Paul’s home to discuss the trip. Most conversations went quickly. Mine lasted a little longer. Paul said I’d made the cut, but he felt I needed to train more intensely to be ready, and I had just four months to get in shape.

“You could stumble your way to the pole in the shape you’re in,” he said, “but it will be a lot more fun if you’re in better shape.”

I asked what role I would play on the expedition. Handling the dogs? Navigating? Communications?

Paul smiled and shook his head. “Craig’s going to be the head cook,” he said. “You’re going to be his assistant. It seems to be the best use of your talents.”

I made it. So did all the others. Okay, so I would be the assistant cook, the lowest-level job on the expedition, mostly cooking ice into water and cleaning dishes. But in the event that the head cook was not able to perform his duties I needed to be ready to step in.

As we left the lodge and headed home, I didn’t care about my role on the team. I was going to visit Santa’s Land!