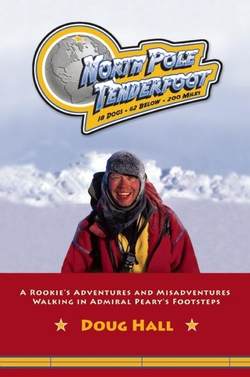

Читать книгу North Pole Tenderfoot - Doug Hall - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 3

Ready … Set … Go

SUNDAY–TUESDAY, APRIL 11–13, 1999

AFTER LEAVING PAUL’S LODGE IN DECEMBER, I focused on fitness. When I first dreamed of going on this expedition I was a poster child for mentally fit—and a clinical case of physically unfit. I didn’t want to be the caboose, the weakest link, the runt of the expedition litter, and so I changed my workout program.

Working out in full gear

Given that fitness was foreign to me, I outsourced my program to personal trainers in a six-day-a-week, often twice-a-day schedule. I lifted weights, trained as a boxer, did aerobic exercises, and took up long-distance swimming, spinning, cross-country skiing on roller skis, and running. I also did cross training in full Arctic gear. My kids thought it was so funny they volunteered to get up early and go to watch me.

Each of the trainers made me their special project. In each case, I was blunt with them. I knew I’d found the right trainer when they responded to my challenge with glee. I especially liked the ones who added a touch of sadistic humor. They took the challenge seriously. I provided an opportunity for them to really apply the intensity of their training.

My biggest challenge was learning what it feels like to work out. Over the years I had insulated myself from fitness through a commitment to not getting hurt. When I exercised and felt pain, I stopped to prevent injury.

In truth, I had been lazy. I didn’t understand good pain from bad pain. I didn’t understand that muscle soreness from a workout was a good thing. It meant I was getting stronger. Although I understood the basics of working out, I didn’t know what it really felt like to be healthy.

The trainers had a common religion: the heart rate monitor. It’s a truth teller. When my mind told me I felt tired, even though my body was capable of more, the monitor would snitch on me, and the trainers would demand more effort.

During the December training trip, I tracked my heart rate while working with the dogs and sleds. While in the snow and loaded with gear, my heart ran above 75 percent of my theoretical maximum rate. When the sled had to be pushed and pulled, my heart rate shot up to 90 percent of maximum.

As the time for the journey came near, I underwent a second heart stress test at Canyon Ranch in the Berkshires. An earlier test at their Tucson location showed that my heart and lungs were in below-average shape. Not good enough. The test involved running as fast as I could on a treadmill for as long as I could, wearing a facemask to measure my oxygen intake and my CO2 output. A nurse stood next to me with what looked like heart jumper cables while I kept thinking, “Sell my clothes, Mabel, I’m heaven bound.”

I lasted twelve minutes in my first test. On the second one I managed twenty-three minutes. Afterward, the Canyon Ranch doctor said, “I have good news and bad news.”

“Give me the bad news first,” I said.

“The bad news is you can’t use your heart as an excuse for not going” he said. “The good news is you may freeze to death, but you probably won’t die from a heart attack. Your heart is in excellent shape.”

The test indicated that I had the maximum heart rate of a twenty-nine-year-old and the VO2 max of a man of twenty-four. Naturally, I’ve been mentioning these results since then to anyone who will listen.

By the time I left for the expedition I had increased the average maximum weight I could lift by 32 percent. For the first time in my life, I could bench press my weight! Not bad for a guy who a year before could only bench press 60 percent of his weight (roughly equivalent to seven small sacks of potatoes).

I was in the best shape of my entire life. Of course, that wasn’t saying much.

After more than a year of intense planning and preparation, I was finally on my way, leaving Cincinnati to travel 3,523 miles to the top of the earth.

On a Sunday we flew to Edmonton, Alberta, to meet the rest of the team, and from there we flew to Yellowknife, then onto Resolute Bay, the Inuit village that served as our point of departure, from which we would fly to a point on the ice at 88 degrees latitude, where we’d be left to our own devices.

In the week before leaving, three events occurred that my imagination fanned into full-blown crises:

Crisis One: On April 8, in Orlando to give a lecture to a trade association, I awoke in my hotel room at 2:30 A.M. with a nasty sinus infection. The world outside was quiet, but my mind exploded into hyper-drive.

What if the doctor said I couldn’t make the trip? What if my condition was contagious? What if the Twin Otter planes that would transport us to 88 degrees were not pressurized and my eardrums burst?

Worst of all, these internal tensions exposed a vulnerability I hadn’t realized until that moment. For the first time, I understood how important it had become to me to make this trip. I had come down with an irrational, nonsensical need to stand on a piece of ice on top of the earth. I had Arctic Fever. The admiral suffered from the same malady.

To me the final and complete solution of the polar mystery which has engaged the best thought and interest of some of the best men of the most vigorous and enlightened nations of the world for more than three centuries, and today quickens the pulse of every man or woman whose veins hold red blood, is the thing which must be done for the honor and credit of this country, the thing which it is intended that I should do, and the thing that I must do.

Later that morning, a call to my office triggered a chain of solutions. By noon, a fast-acting steroid and turbo-charged antibiotic awaited me in Cincinnati.

Crisis Two: That Saturday, I learned of a new demon: diarrhea. Jeff Stamp, a food scientist who consulted at the Eureka! Ranch, called me to report important scientific findings. He told me he’d been eating the food I would be consuming on my way to the pole—six thousand calories each day with a high dose of fat for fuel.

“Within three days,” Jeff reported, “I was dehydrated and in the throws of massive diarrhea. Worst of all, the diet’s high acidity caused significant exit pain.”

EXIT PAIN! Diarrhea! Say what?

I remembered Paul Schurke telling me that he’d had bad diarrhea during his 1986 expedition to the North Pole. Yikes! Not only did my head feel like a truck had run over it, now I had reason for concern over discomfort in my personal hinterlands. I called my brother Bruce, who had once been brand manager for a fiber supplement product, Metamucil. In fact, Bruce had created a mascot for the product that he named Mr. Happy Bowel. It was a cartoon song-and-dance bowel that can only be fully appreciated by the medical community.

Relaying Jeff’s findings, I asked Bruce’s advice. Once he stopped laughing, he suggested I take a Metamucil Wafer after each meal.

“Research indicates that 80 percent of those who do, report a spectacular bowel movement the next day,” Bruce said.

It was music to my ears. I bought two packages of Metamucil Wafers. Crises averted.

Crisis Three: 6:00 A.M. Sunday. No luck sleeping. Boots strewn across the living room floor.

Given that we were traveling on foot, I had to choose the right boot for the trip. I gave it a lot of thought. Waaaayyy too much thought. Each style had its virtues and drawbacks. I even had to choose what size to wear. With a larger boot my feet would be warmer because I could wear more socks. However, if the boots were too large I’d lose ankle support when skiing and climbing over ice.

I laid out all four styles of boots, some in multiple sizes. I’d tried all of them in multiple test runs, both on the December trip to Ely and a cross-country ski trip in Jackson, New Hampshire. My conclusion? Confusion. Nothing seemed to fill all my needs.

The traditional mukluks favored by the Inuit are like giant leather socks. But they wear out easily and provide little ankle support.

Most of the team was going for the big, white Moon Boots created by Paul Weber, who has been with Paul to the North Pole. They’re a high-tech form of mukluk with rubber bottoms and multiple layers of insulation. They’re designed to breathe and release moisture, which also means they aren’t waterproof. Hands down they seem like they’d be the warmest. However, they’re also heavy and don’t offer great ankle support.

Then there are LaCrosse boots. They have rubber bottoms and leather uppers. They weigh a pound less than the Moon Boots. They don’t seem as warm but offer great ankle support and Paul Schurke’s endorsement as the right choice.

Weight is a big issue. I’ve read that the reduction of just one pound off your feet increases your performance by 5 percent. And for me, every bit of extra energy and performance is going to be important.

The last option is a bizarre invention of mine. It’s a multipiece system of footwear built around the New England Overshoes. NEOS, as they’re called, are waterproof overshoes designed to keep stockbrokers’ wingtips dry. I’ve added foot liners, foot wraps, and high-tech ankle braces to make them into the lightest footwear on earth. They weigh half as much as the Moon Boots. In theory they’re the perfect choice. But because they’ve never been to the pole, their durability, warmth, and suitability have not been proven.

At 7:00 A.M., I put a different boot on each foot and ran around outside. I kept trying options until I’d been through all the boots at least once. Finally, I made my decision: I chose the most conservative option, Schurke’s recommendation of the LaCrosse leather boots, and the most innovative one, the NEOS system.

Tori, Brad, and Kristyn decorated the car for the trip to the airport.

I also decided to go with vapor barriers to keep my feet warmer. Vapor barriers are socks made of scuba suit material. You force your foot to sweat inside the barrier, which then holds in the warmth. The feeling can be a little clammy and odd, but your toes are toasty.

By 9:00 A.M., I had all my gear in the bags. Debbie and our children (Kristyn, twelve; Tori, ten; and Brad, eight) took me to the airport in Debbie’s SUV, which they had decorated with balloons and well wishes. We looked like we were headed to a soccer tournament or a wedding.

At the airport, I meet up with Craig Kurz, and my longtime partner in crime, David Wecker, who would be the expedition’s base camp commander in Resolute and our link to the civilized world.

I met up with Craig and David at the airport—just 3,523 miles to go.

As a columnist for the Cincinnati Post, David would translate my dispatches from the ice each day into newspaper columns that would be distributed worldwide via the Scripps Howard News Service, as well as on the Great Aspirations! Web site. Should something go awry—if, say, we needed emergency supplies or a quick evacuation—he would arrange with one of the two Arctic bush-country air carriers at Resolute Bay to make it happen.

Like Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, or maybe more like Abbott and Costello, David and I have shared adventures around the world. We have invented ideas for cookies, cat food, credit cards, cars, and even coffins. We’ve sparked revolutionary thought from the capitals of corporate America to the Imagination Pavilion at Disney’s Epcot Center and some of the most historic castles in Europe.

As the idea of turning my less-than-Schwarzeneggarish self into shape for a trek to the North Pole took shape in my mind, David was among the first to hear of it. In typical fashion, he suggested I was suffering from a polar disorder and advised me to seek help.

It was comforting to have these two good friends on the trip, but it wasn’t without some anxiety. I felt a certain responsibility for them, having done a bit of a sales job to get them to take part in the expedition.

The hugs from the kids lingered longer than normal. I thought I saw a mixture of fear and excitement on their faces. Then I hugged Debbie, who has always supported my crazy schemes, like only someone who truly loves another could.

In our embrace, she whispered in my ear, “You’re ready.”

“Are you sure?” I asked.

“Absolutely!” she said.

I don’t know who’s crazier, me for getting myself involved in stunts like this or Debbie for supporting me. I guess you could say we’re genuinely crazy for each other. (I know it’s sappy, but as I write this story we’ve been together for thirty-three years, and we’re still happily in love.)

At 1:32 P.M., I settled into my seat on the American Airlines flight to Chicago, the first leg of the journey. I knew I’d miss my family, but I felt pulled forward. Debbie’s words washed over me. I had a feeling of peace and steadiness. For the first time in days, I slept well, dropping into a deep sleep as the plane lifted into the air.

Monday, April 12: The team assembled in Edmonton for the long trip north. Before we headed out, I had work to do on behalf of the Great Aspirations! charity. At 6:00 A.M., I began doing radio interviews at the rate of one every fifteen minutes. The expedition generated publicity, but my message was about encouraging parents to believe in their children.

I covered the country from east to west, following the time zones for the early morning commuters. I talked to Boston, Falls Church, Kansas City, and on across the country. Given the hour, I strained to sound chipper. “I’m like a kid on Christmas morning,” I told the morning guy from Spokane’s KXLY radio. “I’m going to see Santa Claus!”

We were selling radio audiences on connecting with their kids.

Jon Paul Buchmeyer—the account supervisor from the aptly named Bragman, Nyman, and Cafarelli, a public relations firm I commissioned, lined up the interviews, along with dozens more for when we are on the ice. The interviews would depend on whether my expensive Iridium telephone technology functioned properly. Jon Paul, who had represented Whoopi Goldberg and Cameron Diaz, was skeptical about the prospects but excited about the potential.

To the guys with the “Al & Rich Show” on the USA Radio Network in Dallas, I said, “This is a bizarre charity. Don’t send money. Please. Instead, sit down and spend ten minutes with a child. It’ll have more of an impact on that kid than any dollar amount ever could.”

To make the Great Aspirations! charity work, we have to generate publicity. And I’m the charity’s P.T. Barnum. My problem is that we can’t claim any firsts, other than the fact that Alan Humphries would be the first Irishman to walk to the North Pole. Granted, I might have pitched myself as the first life member of the International Jugglers Association or MENSA to make the trip, but who would care?

Jon Paul met us in Edmonton to tape “B roll” footage of the trip. TV stations don’t do stories if they don’t have video to go with them, and once we hit the icy trail to the pole, it would be impossible for us to provide it. So Jon Paul wanted to have footage in the can to offer any stations that might show interest.

The team, except for Mike Warren and Corky Peterson, posed for photos at Rabbit Hill.

He planned to tape the team slogging along in the snow. Unfortunately, when we pulled into Edmonton, the snow had melted—and the 40-degree temperature didn’t promise to offer more. But the resourceful Jon Paul had the New York staff make phone calls throughout the area and found a ski resort called Rabbit Hill that had snow machines. They still had a dusting of snow on the ground and they could make more if we needed it.

I nervously approached Paul Schurke about taking the dogs and a sled to the ski resort to cook up some Arctic-y footage.

Paul understood. He also realized that the team might be less enthusiastic about the idea. Paul worked a little marketing magic and presented it to the team as a tune-up trip, a sort of last-minute dress rehearsal.

No one bought it. Some members of the team weren’t interested in staging a situation. One suggested we might as well stage the entire expedition, phoning interviews to radio stations across the world, waxing on about the cold, grueling the conditions as we munched blueberry muffins in our hotel rooms. Two days later, when we were dropped on the ice at the 88th parallel, some of us would think that wouldn’t have been a bad idea.

Paul, Alan, and Celia watch the scene. Alan thought it was a bit absurd.

Rabbit Hill was really more of a bunny hill. But at least it offered some snow. Three camera crews came along to film us—the PR firm’s team along with crews from two of the Canadian television networks.

Paul gave the “experienced explorer” take on the trip.

We put on our bright red expedition jackets, covered with seventeen sponsor patches. We scrambled in the snow as we’d been trained to do, making our actions look as realistic as possible. The only hitch occurred when a black Rottweiler appeared out of nowhere as Alan ran a dog team and sled past the cameras. The dog chased Alan, nipping at his leg when suddenly the nine sled dogs caught its scent and turned on it. I’ve never seen a big bad Rottweiler run away as fast as that one did.

The crews then filmed Paul Schurke, asking him what it’s like to go to the North Pole. Paul gave the big-picture perspective: “The North Pole has often been compared to a horizontal Everest. It has the same extremes of climate and remoteness.”

“I’m scared to death,” I explained.

Then they interviewed me as the head of the charity. Jon Paul had briefed me on what to say, but in the anxiety of the moment, my response didn’t come out as I expected. Over a shot of the dogs barking, the announcer said, “The dog team is ready to go. But the man behind this expedition may be having second thoughts.”

Then the camera turned to me and I said. “I’m scared to death. To be perfectly honest, it is, absolutely terrifying.”

Not exactly the bravest statement I could have made, I guess. But at least I was honest.

Before such challenging expeditions, it’s common to engage in a ritual of gathering and selecting gear, a practice that probably dates back to prehistory, when cave dwellers squatted around fires chipping away at flint spearheads, selecting the truest arrows, restringing bows, assembling food caches, and articulating their anticipations in jagged streaks of war paint.

Back at the hotel, Paul told us to examine our gear and make our final selections on what we would take. I had spent hundreds of hours and thousands of dollars searching for the most effective gear. From long underwear to high-tech communications systems, I had given a lot of thought to my equipment, and I enjoyed going through it one last time, picking the things I most needed.

Bartlett (in the center) had a real “toughness” to him.

I looked again with pride at the expedition jacket with its patches. In the weeks before leaving, I’d put it on many times to see how I looked. I even had my picture taken in it before the trip. Real explorers definitely have a look about them that says they’re serious, and in the photo above, Bob Bartlett looks like a rugged explorer. In the picture of me in my winter gear, I don’t evoke quite the same ruggedness. However, I was more interested in promotional power anyway, publicizing the roles that Ziggy and Fuzz would play on the trip.

Never in history had an explorer posed with two cartoon characters — Ziggy and Fuzz.

Though posing with cartoon characters may not seem appropriate for an Arctic explorer, I think the admiral would have gone along with it. When it came to raising money and generating publicity he was very aggressive. He endorsed cigarettes, ammunition, Pianolas, rifles, pencils, razors, watches, toothbrushes, whiskey, toothpaste, socks, and cameras. He even promoted the “Peary coat,” a heavy fur greatcoat that he designed.

When it came to selecting gear, the admiral was very much a scientist. He tested everything. He described the importance of preparation this way.

Thorough preparedness for a polar sledge journey is of vital importance, and no time devoted to the study and perfection of the equipment can be considered wasted.

That evening, Paul called us together to review key issues and talk about gear. He opened two gun cases. “Each sled will have a gun,” he said in a serious tone. “They’re to be used in the case of a polar bear attack. It’s unlikely, but you need to know where the guns are. Just in case.”

The more he talked, the more my fear grew.

Paul’s gear was amazingly sparse. Mine weighed twice as much.

He then showed us his gear. We were most impressed not by what he had but by how little he had. He was taking a few spare clothing items along with a mug, plate, and spoon tied by string to a bowl, a pee bottle for use during the night, and a small copy of the New Testament. That was it. I lifted his pack, then mine. I was aghast. Mine was at least twice as heavy. No, probably three times.

Paul made it clear that no team member should bring more than twenty-five pounds of personal gear—pack and all. He said that the three most important items were those that related to protection for your eyes, hands, and feet.

“On every trip, I’ve ended up with mild sun-blindness from the reflection off the snow,” he said. He also said he always wished he’d packed more liner socks and liner gloves.

I wasn’t sure about my footwear, but I was confident about my protective gear for eyes and hands.

After my local Lenscrafters manager had called their store in Anchorage for a recommendation, I bought two pairs of prescription glasses each with an extra polarization coating.

As for hand protection, I had two favorites—a pair of handmade wool mittens I’d bought on Prince Edward Island and a set of Plunge Mitts designed by Paul’s wife, Susan. Equipped with two inner liners, they look like the giant potholders. Susan designed them especially for polar treks.

Paul closed the meeting by telling us to ready our gear for final inspection. When he checked my pack, he said it seemed a little heavy. “Do you really need all this stuff?” he asked.

After he left, I unpacked the pack, looking for things to eliminate. I felt the anxiety building again. What should I leave behind and would I regret leaving it when I was at the pole?

The admiral wrote about the importance of keeping gear as light as possible.

Careful attention must be paid to even the slightest details. Everything should be just as light as it can possibly be made. For the number of miles a party can travel depends on weight carried. Every reduction that can be made conserves mental and physical energy.

As I sorted through my gear, my anxiety built into a full-scale panic. Admiral Peary would have called it an attack of Tornarsuk, the Arctic Devil.

Tornarsuk was the god of the Inuit underworld. The Inuit believe that all departed spirits reside in the underworld, beneath the land and sea. Their souls are purified in preparation for their travel to the Land of the Moon—or Quidlivun—where they find eternal peace.

The early European explorers translated Tornarsuk into a Satan-like being to create alignment with the Christian view of the world of good and evil. In time, the name became slang for Polar Hysteria.

In medical journals Arctic panic is technically listed as Piblokto. It’s a feeling of being possessed, a simultaneous mania and depression. It feels like an urgent need to do something, anything, coupled with an inability to make a move. In the worst cases of Piblokto, victims tear their clothes off and run naked outside.

Fortunately I was not at that stage.

I was, however, clearly “possessed” by fear. I knew the fear was irrational, that it made no sense, but I couldn’t stop it. Panic took control of me.

Obsessively, frantically, I began swapping out my gear—my metal bowl for a plastic one, a special knife engraved with the expedition logo for a Boy Scout pocketknife. With all the gear removed from my pack, I realized that the pack itself was part of the problem. Instead of picking a mid-size pack, I’d bought an oversized one because I figured it would be easier to pack in the cold. As I held it I realized there had been a real reason why Paul had suggested the smaller one.

It was 7:00 P.M. as I tore open the Yellow Pages and found Valhalla Pure Outfitters. Thirty minutes later, after borrowing a rental car and driving into town, I was in front of the store.

I sauntered inside, trying to act like a real explorer, following advice Paul Brown, founder of the Cincinnati Bengals football team, gave his players when they scored: “Act like you’ve been there before.”

I approached the two staff members behind the sales desk and said, “Hi, I’m going to the North Pole.”

I tried to act like a pro. But they’d seen me say on TV that I was “scared to death.”

They looked up and laughed. “We know,” the lady said. ‘We saw you on the news.”

My television comments about being “scared to death” apparently made quite a hit in an outfitter store.

Forgetting my poise I said, “I really need some help. I’m missing some key gear.”

A staffer named Matt, a real outdoors fanatic, looked at my list. First, he found a backpack that weighed half as much as mine. Figuring that I probably needed help, he made the all-important adjustments to the waist belt and the multitude of straps to reduce stress on me and my back.

Next, he got a balaclava—a sort of portable hood that protects your neck, head, and face. I’d never cared for these, perhaps because of my distaste for neckties. In my role as a creativity guru, I’d called them neck tourniquets, horrible pieces of apparel that served only to cut off the flow of oxygen-rich blood to the brains of corporate executives. But I was heading for a world far removed from the corporate boardroom, one where protection of neck and face is critical.

Long johns—I had medium weight and ultra heavy. After seeing Paul’s gear, I wanted a pair of lightweights, especially for skiing. A pee bottle—Paul had been persuasive about the value of having an extra water bottle that could be used as a urine receptacle during the night to eliminate the need to leave the comfort of one’s sleeping bag.

The gaiter and long underwear were easy choices. The pee bottle was a bit more difficult. What size would I need?

I immediately rejected a thirty-two-ounce bottle because it was the same size as my water bottle, and I definitely didn’t want to get the two confused. They had a smaller bottle, but the top was small, and I was concerned about aim. After some digging in the back of the store they found me a sixteen-ounce bottle with a wide mouth. Eureka!

Selection of the right pee bottle was challenging. Later I would learn that I made the wrong choice.

Heading back, I felt myself start to relax, feeling that I was finally ready for the expedition. Resolving the gear issues gave my mind a space to relax.

I decided to take a swing through Edmonton before heading back out to the airport. I stopped at a bookstore to buy a book to take with me. I went to the information desk and asked, “If you were going to the end of the earth, what one book would you take?”

The clerk gave me a blank stare.

I tried again, “If you were on a deserted island what one book would you want to have?”

“I don’t know,” she said. “Maybe a poetry book or a Bible.” She pointed to the self-improvement section, figuring, I guess, that I needed it.

I ended up buying a book of Ben Franklin quotes, Franklin being my personal hero. I figured that if it didn’t inspire me, I could burn it for heat or, in a pinch, use it as toilet paper.

As I walked toward the checkout I picked up a New Testament. I figured that if it was good enough for Paul it was good enough for me. Besides, given the emotional roller coaster I was riding, it might help calm my mind.

I returned to the hotel at around 8:30 P.M. and carried my gear to my room. I was feeling good—too good. As I moved my gear into the new pack I suddenly realized that I’d lost my mittens. My big, blue, double-insulated plunge mitts were missing. I tore through my bags, my jackets, my gear, turning everything inside out.

The mittens were critical. I had to have them.

I backtracked. I’d had them at the ski resort that afternoon. I remembered taking them off to demonstrate the satellite phone. I was up and out of the room, running down to the truck that had taken us to the resort and back.

I pawed through the truck and the dog crates. Nothing. I ran back upstairs to look again. Nothing. Then back to the truck again to look under the seats and beneath the sleds. Nothing.

Tornarsuk the fear dragon appeared again.

I called Paul’s room and asked if he’d seen my blue plunge mitts. Nope. I called Craig, then David. Double nope.

After one more trip to the truck and back I was in a state of panic.

I had no recourse but to call my new friend Matt at Valhalla Pure Outfitters.

“Hey, it’s me again, do you have any really really warm mittens? You do? Excellent! What time do you close? In ten minutes? Uh, um, okay. Do you think it would it be possible for someone to bring a pair of those gloves to me? It would? You’re awesome, man!”

Twenty minutes later, I had a spanking new pair of two hundred-dollar mitts. I gave Matt a hundred-dollar tip. I also gave him a Great Aspirations! Expedition patch and my eternal thanks. He seemed happier with the patch than the money.

Tuesday, April 13: It was 6:25 A.M. My blind terror from the previous night’s exertions had worn me out, giving me six hours of uninterrupted sleep, the most I’d gotten in five days. The curse of my missing mittens had turned into a blessing. Amazing.

But a sudden spiral of doubt started turning again. What if I didn’t have the energy to make this trip? What if, despite all my training, I really wasn’t ready? What if I was just totally nuts? One conclusion seemed clear: I had no business being on this trip. None whatsoever.

I opened one of the notes Debbie and the kids had secretly packed in my bags. Without me finding out, they had packed a collection of small, folded notes in every nook and cranny of my pack. I had found them the day before and placed them all in a plastic bag. I’d decided to open one whenever I really needed a boost of confidence. This seemed like one of those moments.

I grinned at what I read:

My wife had the kids secretly stash notes in my backpack.

My wife Debbie’s support for this crazy idea went far beyond what would be considered reasonable.

Instantly, I had more courage. My family’s faith in me was greater than my faith in myself.

At breakfast, in front of the whole team, Paul asked about the status of my blue plunge mitts. Terrific, I thought. Expose me as a total fool for losing my mittens.

With a big, pearly white, totally engaging smile, Paul told me he’d found them in the truck and put them in the spare clothing bag.

Paul found my mittens and enjoyed the site of watching me panic. I didn’t mind being the “fool” as long as I had my mittens.

What a relief! On second thought, what the hey?!?! If he’d found my mitts in the truck, then, well, you get my drift. What kind of psychological magic was he working now? What lesson was I supposed to learn? Or was my role to be the entertainment for the team?

I remembered something Paul had said in an interview in the New York Times. “Trips are too predictable when everyone’s a veteran. It’s much more interesting to watch a bunch of people who are still trying to figure out what to do.” It looked like I would be providing lots to watch.

By 7:30 A.M., we were packing the dogs, sleds, and gear at Canadian Air Cargo. It took two hours to load it all onto the shipping pallet that would go into the plane.

The scene was a bit chaotic.

Paul was negotiating on the fly, so to speak, with the Canadian Airways representative, working to make sure all our gear was loaded. The issue was weight. The airline was used to this game. The seats had been removed from the front half of the passenger compartments. A set of doors on the side of the plane allowed for loading pallets. Our eighteen dogs in their crates with our sleds filled one pallet. There were also several pallets of perishable goods like eggs, lettuce, and bacon.

The dogs were loaded into kennels and onto a pallet.

At 11:30 A.M., we finished loading, and I took my seat in the rear for the flight through Yellowknife to Resolute. I’ve never seen so much carry-on luggage before or since.

A woman in front of me shrieked when I went to put my bag in the overhead compartment. “Watch my donuts!” she hollered. She must’ve been packing six dozen.

I settled in next to Paul Pfau, the last person to join the expedition. A deputy district attorney in Los Angeles, Paul had been climbing mountains for thirty years. He’d led four expeditions to the summit of Mt. Everest. In fact, he was climbing Everest—”gratefully so,” he says—when his colleagues stood in the global spotlight prosecuting the O.J. Simpson murder trial.

You meet the strangest people on an Arctic expedition.

Eager to talk, I shared some of my anxieties. I asked Paul how he dealt with fear.

“It’ll be good to be home,” he responded.

Huh?

He spoke with quiet intensity. I felt like I was listening to Yoda from Star Wars. Certain phrases rose to the surface:

The front of the plane held the pallet with dogs and gear.

“Honor the process … Do your best each day … Burst your comfort zone … Value each step … Make each day’s steps better than the steps you took the day before.”

He was on a roll, and I listened intently.

“Focus on both the big picture and the small details … No detail is too small … Never underestimate what goes on in your head and heart … Goals are wonderful, but staying alive is the real goal … On the adventure you’ll find yourself getting into a rhythm, but it’ll still be nice to be back. It’ll be good to be home.”

I madly scribbled notes. Maybe somewhere in all this, I might get the answer to why I was obsessed with taking this crazy trip.

“The overall experience of such an expedition keeps feeding you—whether it’s good, bad, or in between—until the day you leave this planet,” he said.“For me, there’s been an ever-changing motive for taking on major challenges. Over the years, this has evolved into the pursuit of intangible, enriching experience.”

I kept scribbling, not wanting him to stop. And he kept going, speaking in ornate phrases, as if he’d prepared the talk before we left.

“The act of climbing a difficult mountain results in the convergence of the physical, mental, and spiritual realms,” he said. “I expect to experience the same sense of coming together here. I know the Arctic zone is a wonderfully beautiful part of the planet and anticipate that it will yield the kind of enriching experience that’s been a life force for me. And I know it will be one of those ever-enriching experiences that will stay with me forever.”

Our conversation lasted nearly an hour. In some ways, what Paul said disturbed me. Who were these crazy people? In other ways, I found it fascinating.

I dozed briefly, then was awakened by a flight attendant offering café Franklin—a combination of coffee, brandy, and whipped cream. She said it was named after the “famous polar explorer Sir John Franklin.” I flinched. He was “famous” because he DIED. He was killed along with 128 men in the greatest disaster in the history of the North and South Poles.

I mumbled to myself, “I don’t want to be that famous!’

Three-and-a-half hours later we arrived in Resolute Bay, Nunavut.

A deep penetrating cold blasted us as we left the plane, the temperature standing at minus 5 degrees. With the wind chill, my temperature gadget, a special tool that measured temperature and wind speed, read minus 35 with the wind. It was my first hint of the incredible cold that would envelop us around the clock.

We unloaded the dogs, ran out two lead lines, and clipped the dogs to them. Keeping the dogs separated on the line makes it harder for them to fight each other. Sled dogs constantly test each other for dominance, which means they can break into a fury with no warning.

We trotted into a mechanic’s shop to warm up. Inside, Paul discovered that in the chaos of leaving the plane, he had left behind a small pack, one containing maps, contact information, our radio codes, his sextant, and other critical information.

We looked at him with fear in our eyes. This was a huge problem that couldn’t easily be solved. The plane with Paul’s bag had already departed for its return trip south. It wouldn’t return for a week.

Resolute Bay has a population of not quite three hundred, except for the “silly season” when fools like us make attempts at the North Pole or go polar bear hunting.

Paul seemed to go away for two minutes. He stood next to us physically, but his mind was focused elsewhere. He remained calm, calling on some strength apart from himself. Then, as quickly as it had risen, his wall of isolation fell away.

“Worse things can happen,” he said.

Bill Martin offered to check with the tower to see what might be done. Paul nodded, and we slowly left the mechanic’s shop, heading for Resolute Bay, where the view is of another world—an utterly stark alien-looking terrain, whiteness cast in a pale blue glow of the endless sunlight of the Arctic spring.