Читать книгу One Best Hike: Mount Rainier's Wonderland Trail - Doug Lorain - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2

Have a Safe (And Fun) Trip

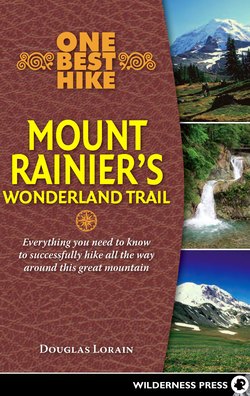

Opposite: Mount Rainier from pond in Spray Park

Despite all the bad movies you may have seen about the outdoors, the greatest dangers you are likely to encounter while backpacking are not angry bears, crazy hunters, hungry mountain lions, or “evil” rattlesnakes but more mundane threats such as being wet and cold for too long (which sounds merely uncomfortable but can actually kill you) or falling down and hurting yourself. These concerns might not be “sexy” for the moviemakers, but they are by far the most common types of dangers faced by hikers on the Wonderland Trail, so you need to know how to avoid them to have a safe trip.

Hypothermia

Hypothermia occurs when the body loses more heat than it can produce, thus causing the body’s temperature to drop. When it falls below about 95ºF (only 3.6º below normal), hypothermia sets in and symptoms begin to occur (see below). Once your core temperature drops below about 78–80ºF, your brain and heart cease to function. People who “freeze to death” actually die of hypothermia long before they freeze.

It does not have to be bitterly cold for a person to suffer from hypothermia. In fact, the overwhelming majority of people who die from hypothermia do so at temperatures well above freezing—from 30–50ºF is most common, but you can get hypothermia when it is 60ºF or more. Typically, people start to feel the effects of hypothermia when they and their clothes are wet from rain or snow and temperatures are in the 40s or 50s. Wind dramatically compounds the problem. Sound familiar? If not, reread the section on “Weather” and you will quickly see why hypothermia is the number one danger to hikers in Mount Rainier National Park. It cannot be stressed enough how important it is that anyone contemplating hiking the Wonderland Trail be equipped with not only the right gear and clothing to avoid hypothermia but also the skills to recognize the symptoms and the knowledge of what to do to reverse it.

Hypothermia can set in remarkably quickly, and because one of the symptoms is a loss of mental functioning and good decision-making skills, you need to regularly monitor both yourself and your companions, so that you can catch the warning signs before your decision-making abilities are impaired. This is particularly crucial if the weather is wet, windy, and cold. The first symptom is shivering, which is your body’s attempt to warm itself as its core temperature falls below 95ºF. As your temperature continues to fall, you develop signs of confusion and lack of manual dexterity. Once your body’s temperature falls below 90ºF, you may no longer feel cold but will probably become incoherent and have severe lack of judgment. Things are extremely serious at this point because your body is losing its ability to rewarm itself, and it must receive heat from an outside source. Any further loss of body heat will cause the body to slowly shut down, and you will eventually die. Reversing severe cases of hypothermia can only be done in a medical facility, which is not a realistic option while hiking in the wilderness of Mount Rainier National Park. Therefore, it is very important that mild cases be caught early and treated in the field before they become severe.

You can treat mild cases of hypothermia by getting the affected individual out of the rain and wind as quickly as possible and have him or her move around vigorously. Have the person remove his or her wet clothing and don something dry and warm. If the person is conscious, feed him or her warm liquids, such as hot chocolate or soup, that can be swallowed and digested easily. Place the person in a prewarmed sleeping bag alongside bottles that are filled with warm water. If the hypothermia symptoms are more advanced, have the person strip and place him or her in a warm sleeping bag with one or two other people (also stripped) who curl around the victim and provide skin-to-skin warmth. Despite bad movie advice to the contrary, do not give the person alcohol, which will open restricted blood vessels and allow blood to flood the extremities, making the person feel warmer but only at the expense of the body’s core, where the warmth is critically needed.

As with most problems, a far better plan than treating cases of hypothermia is to avoid them in the first place. The best way to do this is to wear adequate clothing and to try to avoid potentially dangerous situations, such as hiking for prolonged periods along exposed ridges when the weather is cold, windy, and raining or snowing. As previously mentioned, you absolutely must carry good raingear that will protect both you and the clothes worn beneath your raingear from getting wet. The raingear should also be made from material that serves as an effective shield against the wind. After good boots, a quality rain jacket is probably the single most important item that you will carry on your trip around the mountain. Rain pants may also help to protect your lower body. Without them, your legs will get absolutely soaked, if not from the rain itself then from all the water that collects on plants that you brush up against while hiking. A warm knit pullover cap is also a requirement because an enormous amount of your body’s heat is lost through your head. In clear and cool weather the knit cap will also make evenings around camp much more comfortable and keep your head toasty while you are sleeping.

In addition to the right clothing, you should keep your body well hydrated and, most important, well fed. At regular intervals refuel with high-energy foods, such as energy bars, nuts, and candy, which provide quick calories for your body to burn and warm up. Have these foods easily accessible, so you don’t have to stop to dig them out of your pack. When you stop to rest, do so out of the wind and cover up as quickly as possible because your body will rapidly cool down once you stop hiking.

Accidents

As the old saying goes, accidents happen. And despite what your ego and emotions would like to believe, they can and do happen to you. Even the most experienced and best-conditioned hikers sometimes lose their concentration, step on a loose rock or icy patch, and find themselves either flat on their backside or, much worse, tumbling down a brush- or rock-covered slope. The rugged terrain along the Wonderland Trail is not only spectacularly scenic but also potentially hazardous. Badly twisted ankles and knees, broken bones, and severe cuts are just a few of the accident-related injuries that strike Wonderland Trail hikers every year. Most of the time these result in nothing worse than a lot of discomfort and a ruined trip, but occasionally they can be a threat not only to your vacation plans and ego but also to your life.

I realize that this is going to sound simplistic, but the best way to avoid falling and injuring yourself is to use common sense and not do anything that overextends your body or that a disinterested observer might uncharitably describe as “stupid.” Before you cross a raging stream by walking over that slippery log, scramble out to that dangerously exposed point merely to get a slightly better picture, or step on that wobbly boulder without checking its stability first, remember that a hospital or, for that matter, any kind of trained medical assistance is a long way (and, more important, a long time) away. It is also worth remembering that despite what your ego would like to believe, you probably aren’t 18 anymore and your body more than likely is not as strong and limber as it used to be. Unfortunately, clear thinking like this becomes increasingly difficult when you are tired at the end of a long day on the trail.

Here are a few tips to avoid getting into accidents while on the trail:

1) Develop the habit of taking a deep breath and considering things before doing anything that could be dangerous. Initially this will seem a bit ridiculous and probably feel like overkill, but eventually it will become second nature and could save your life.

2) Take regular rest stops, both to refresh your body and to keep your mind sharp. This is easy to do on long uphills because physical exhaustion will require that you take a breather. What far too many people forget to do, however, is to also take rest stops on longer downhills. People don’t feel winded so they figure that they don’t need a breather. Your knees and toes will greatly appreciate it, however, and, at least as important, your mind will have a chance to recharge and be more careful about foot placement and other safety issues.

3) Avoid cross-country travel unless weather conditions allow for easy navigation, you are experienced in off-trail hiking, and the terrain is safe for travel.

4) Be especially careful when crossing steep snowfields or anywhere that ice has formed on the trail—a frequent occurrence because mornings can be frosty in the mountains at any time of year.

5) When hiking downhill, take short, measured steps and watch carefully for hazards such as ice, mud, wet rocks, roots, and loose gravel. It is also a good idea to use a hiking staff or pole (some people use two) to help with your stability.

6) Finally, plan your trip to avoid long descents at the end of the day when you are probably going to be tired and are more likely to make mistakes.

Blisters, Aches and Pains, and Injuries