Читать книгу Bruce Lee: Sifu, Friend and Big Brother - Doug Palmer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеThe Road to Seattle

BRUCE’S FATHER WAS a well-known Cantonese opera and movie star. Toward the end of 1939, he went on an extended tour of Chinatowns across the United States. Bruce was born during the tour, in San Francisco, on November 27, 1940. It was not only the Year of the Dragon, but also the hour of the dragon in the Chinese zodiac, the dragon often considered the most propitious of the twelve zodiac signs.

His parents named him “Jun Fan” (spelled “Jun Fon” on his birth certificate) in Cantonese, which could be interpreted as “Shaking Up San Francisco.”4 The nickname he was given as a child by his family was “Mo Si Ting,” or “Never Sits Still,”5 because of his restlessness. But the name that he came to be known as later was “Siu Lung,” or “Little Dragon,” his stage name as a child actor in Hong Kong.

His mother, Grace Ho, was Eurasian. The extent and origin of her European blood is a matter of some uncertainty. Her father was a prominent Chinese business man who was ostensibly half Dutch, but may have been entirely Chinese. Her mother may have been a Eurasian concubine, or a secret mistress who was entirely English.6 Doing the math, that would mean that Bruce was anywhere from one-eighth to three-eighths Caucasian. He didn’t try to hide that, but I recall him only mentioning the fact that he was part white in passing. Throughout the time I knew him he proudly identified as Chinese.

When he was born, the Second Sino-Japanese War had been waging for several years. The Japanese occupied much of northern China and various coastal areas, including areas around Hong Kong, which was then a British Crown Colony. Some of his father’s opera colleagues chose to stay in the U.S., or were stranded there when war broke out between Japan and the U.S. One of those was Ping Chow, who eventually ended up in Seattle and with his wife Ruby opened a restaurant there, called “Ruby Chow’s.” Since Bruce’s parents had left their three older children in Hong Kong with his paternal grandmother, then 70, their choice to return was not really much of a choice.

Bruce and his parents left San Francisco to return to Hong Kong when Bruce was less than six months old, arriving by boat in May of 1941. He soon became dangerously ill and nearly died. Several months later, in December, several hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invaded Hong Kong. Bruce was nearly five when the Japanese surrendered and Hong Kong reverted back to being a British colony. When he started school, he was still a skinny kid. He was also near-sighted and wore thick glasses. He was often picked on, but fought back.7

By all accounts, the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong was brutal; the British, although less brutal, left no doubt as to who was in charge. Both periods left an imprint on his character.

He had no problem tapping into Chinese nationalist feelings in his movies. His second movie in Hong Kong after unsuccessfully trying to break into Hollywood, Fist of Fury, made in 1972 with Japanese martial artists as the primary villains, was set in Shanghai during the early 20th century. Sections of the city were then controlled by foreign powers. In one scene, he is denied entry to a park with a sign that declares “No Dogs or Chinese Allowed.” After being taunted by a Japanese man who tells him that if he behaves like a dog, he will be allowed in, he beats up the man and his friends and kicks the sign to smithereens.

Recent scholarship has cast doubt on whether or not signs with that exact wording ever existed, but their existence was unquestioned in the Chinese public mind as a symbol of Chinese humiliation by foreign powers. Bruce certainly believed that such signs were a reality in Hong Kong before the war and during the Japanese occupation.

But as much as the Japanese occupation left its mark on him, Bruce never evidenced any prejudice or ill will toward individual Japanese. His first serious girlfriend in Seattle, Amy Sanbo, to whom he proposed, was a Japanese-American, as was his good friend and assistant, Taky Kimura, who ran the Seattle gung fu school when Bruce later moved to California. When I introduced him to the woman I was to marry, Noriko Goto, a student from Japan, he was gracious and welcoming. There were also other Japanese from Japan that he befriended.

He was certainly aware of the history of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, and undoubtedly heard stories from his parents and others, but probably had few direct memories of his own from that period. In any event, he seemed to have no problem in separating his views of individual Japanese from his views of Japan’s historical occupation of China and Hong Kong.

His attitudes toward the British, on the other hand, seemed more visceral, perhaps because he encountered them as real people as he was growing up, particularly in the form of sailors on leave in Hong Kong. On more than one occasion I heard him tell of run-ins with British sailors who were over-confident in facing what seemed like a skinny bespectacled Chinese kid much smaller than they. One of Bruce’s techniques, when the sailor raised his hands in a boxing stance, was to clap his hands and yell, to focus the sailor’s attention on his hands, followed quickly with a straight snapping kick to the groin. He and his posse also tangled with British students from another high school.

British sailors and students were not the only ones Bruce brawled with as a teenager. The Hong Kong streets were tough, and according to Bruce as well as his family he got in fights constantly. But although he had practiced some t’ai chi with his father, he wasn’t into it and hadn’t yet had any formal gung fu training when he first began getting into scrapes. His first formal lessons were from Yip Man, a well-known teacher of Wing Chun. Most accounts say he started with Yip Man in 1953, when he was thirteen, but one claims that it wasn’t until after getting kicked out of his first high school (Lasalle) and starting a new one (St. Francis Xavier) in September of 1956, when he was still fifteen.8

His main instructors at Yip Man’s school were apparently two older students, William Cheung and Wong Shun Leung. The reason for that may have been that some of his fellow students tried to get him expelled from the school (using the fact that he wasn’t “pure Chinese” as one of their arguments), and as a compromise Yip man had him study with Wong and avoid the main class for a while.9 Wong was an experienced and renowned street fighter who mentored Bruce, encouraging him to hone his classroom skills both on the streets and in bare knuckle matches on rooftops against other gung fu schools. Bruce’s fights did not slow down; if anything, they became more frequent.

By the time he was eighteen, his family had decided he needed a fresh start. In April of 1959 they literally shipped him off to the States on an ocean liner in third class with a grubstake of a hundred dollars, before he had even graduated from high school.

I have read various versions of the reason for his leaving so precipitously, including that he defeated the son of a triad leader in a fight and that he needed to leave town to avoid a contract that was out on him. In another more credible version,10 he beat up the son of a powerful family that complained to the police, who warned his parents that he would be arrested if he didn’t shape up. I never heard Bruce mention the exact reasons for him being packed off to the States, but he spoke often about his numerous fights and all accounts seem to agree that his family sent him off because he was constantly in trouble in Hong Kong. The fact that he was already an American citizen perhaps suggested the solution.

He was by then a well-known child movie actor, but that did not dissuade his parents from sending him away. In fact, his father had forbade him from acting in any movies for several years as a punishment for his misbehavior. Ironically, just as he was preparing to leave he was allowed to appear in one last film, The Orphan, which increased his popularity in Hong Kong as a star dramatically. But the die was already cast.

Three more matters of note occurred in the year or so prior to his departure. One was the proficiency he gained in the cha-cha, even winning a Hong Kong-wide cha-cha contest in 1958. He applied the same skill he did in mastering gung fu forms to choreographing his dance moves. The cha-cha was one of his few passions outside of the martial arts, and served as an ice-breaker in social situations. On the boat over to the States he gave lessons to passengers in upper-deck cabins, and he carried a card with his 108 different cha-cha moves in his wallet for many years.11

The second matter was his one foray into martial arts as modified for sport—an intermural boxing match he was persuaded to participate in by one of the teachers at his high school. Although Bruce won the bout handily, against an opponent who had won that weight division for the three previous years, knocking him down repeatedly, he was frustrated by the limitations of his punching power with boxing gloves and his inability to put his opponent down for the count.12 Although in later years he used modified boxing gloves and other equipment for sparring, the experience solidified his distaste for contests with restraining rules or gear. He forswore competing in any karate-style competitions where points were awarded for landing punches or kicks in circumscribed areas, and insisted in his real matches that they be full contact with no rules of engagement as to where or how one could strike.

Lastly, in the few months before his departure he learned some showier forms and techniques from a teacher of northern style gung fu, including a basic praying mantis set. He was already thinking of teaching gung fu in the States, to augment his income. He figured he could teach the northern styles to students who wanted showmanship, and Wing Chun to those who valued practicality.13

When it was time to leave, his family and friends saw him off at the dock. After an ocean voyage of more than two weeks, he landed in the city of his birth.

BRUCE STAYED IN San Francisco for the summer with a friend of his father. He lasted only a week as a waiter at a restaurant where his father’s friend got him a job, but made some pocket money teaching cha-cha in San Francisco Chinatown and across the Bay in Oakland.14

In early September of 1959, Bruce moved up to Seattle to finish high school. Fook Yeung, another old friend of his father, then a chef at a Seattle restaurant, drove down from Seattle to bring him up.15 From then until he went back to Hong Kong to visit his family in the spring of 1963, he lived at Ruby Chow’s Restaurant and worked there as a dishwasher, busboy and waiter. Fook Yeung was also a gung fu practitioner, mainly a devotee of the Praying Mantis school, and soon taught Bruce some of its forms. 16

Ruby Chow’s was an eponymous restaurant located in Seattle on the corner of Broadway and Jefferson, a short block or so away from the parking garage where Bruce later taught his classes. It was one of the first higher-end Chinese restaurants in Seattle outside of Chinatown, if not the first, and most of the customers were non-Chinese, including local political figures.

The restaurant building was an old Seattle wood-frame mansion that had been retro-fitted into a restaurant with boarding rooms upstairs. Bruce lived on the second floor in a room that was more like a walk-in closet, located partly underneath a stairway leading up to the third floor. I never saw his room, but by all accounts it was sparsely furnished, with the bathroom down the hall. According to Skip Ellsworth, one of Bruce’s early students, Bruce slept on a mattress directly under the sloped ceiling on the underside of the stairway, with his clothes neatly folded and stacked alongside. A wooden fruit-box served as a desk; a single naked light-bulb hung down on a wire from the ceiling, above the fruit-box.17

Ruby was a formidable woman with a beehive hairdo and a strong personality, a powerhouse in Seattle’s Chinese community who later became the first Asian-American elected to the King County Council. Ruby expected Bruce to work for his keep and put up with the high-handed behavior which some of her customers displayed. To say that Ruby and Bruce had a personality clash would be understating it. No doubt she thought of him as a young whipper-snapper, an ungrateful freeloader who expected to be treated as a pampered houseguest.

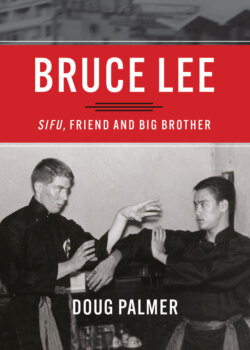

Bruce in front of Ruby Chow’s, Seattle, circa 1960 Courtesy of the Bruce Lee Family Archive

Ed Chow, Ruby Chow’s eldest son, a year-and-a-half older than Bruce, was the commentator for the “Chinese boxing—judo demonstration” at the Seattle University fraternity smoker the following April given by Bruce and a Japanese judoka. I don’t know if Ed was attending Seattle University at the time, but the campus was practically next door to the restaurant. Perhaps some students or faculty were customers at the restaurant and came across Bruce there.

Bruce was also well-known for his sense of humor and corny jokes. One of his favorite jokes perhaps resonated with him because of his experience at Ruby Chow’s, straining to keep his temper in check when he was treated poorly by a boorish customer. As told by Bruce with his distinctive panache, an American walks into a Chinese restaurant, sits down and orders fried rice. The Chinese waiter replies, “OK, one fly lice.” The American laughs and says, “No, Charlie, it’s not ‘fly lice’—it’s ‘fried rice.’” After that, every time the American would come into the restaurant he would tease the waiter and yell out, “Hey Charlie, get me some ‘fly lice!’” The waiter grew very annoyed at this, so he began practicing the correct pronunciation at home. Bruce would imitate the waiter practicing at home in front of a mirror, gradually improving his pronunciation until he could say “fried rice” perfectly. The waiter could barely contain himself until the next time the American walks into the restaurant and calls out, “Hey Charlie, get me some ‘fly lice!’” Whereupon the waiter marches over and draws himself up proudly to confront the American. “It’s not ‘fly lice’—it’s ‘fried rice,’” the waiter says, enunciating slowly and carefully. “You Amelican plick!” Bruce would deliver the last line with gusto in a stereotypical Chinese accent and then crack himself up.

In any event, Bruce spent as little time as possible at the restaurant, and I got the distinct sense that he was counting the days until he could move out on his own. But he put up with it for nearly four years, until he returned to Seattle from a visit back to Hong Kong in 1963. I sometimes wonder if he needed to get the blessing of his father to move out, since his father had arranged for him to stay with Ping and Ruby in the first place. Most likely, it took a while for him to build up the confidence that he could make it on his own, teaching gung fu classes. By the time he went back to Hong Kong he was earning enough money that he could make the move.

Soon after arriving in Seattle he also enrolled at Edison Technical School to get his high school diploma. The building where Edison was housed, on Broadway in the Capitol Hill neighborhood, is now part of the Seattle Central Community College campus. His first gung fu students were fellow students at Edison.

In addition to working at Ruby Chow’s and going to school, he continued his gung fu training. He had a wooden dummy shipped from Hong Kong, which he would pound away at to practice his chi sau and strengthen his forearms.18 He also began to participate in demonstrations, including with Fook Yeung.19

BRUCE WAS STREET-WISE in Hong Kong, but was still learning the way things worked in America. So it was not surprising that he was drawn to some of his fellow students at Edison, who were older and packed full of hard-earned street smarts from this side of the ocean, and who became his first students.

The first one was Jesse Glover, a husky black man with a brown belt in judo. Jesse was then twenty-six, six years older than Bruce. He first saw Bruce in a demo in which Bruce appeared with the Chinese Youth Club, following a cha-cha performance which Bruce put on. Jesse had recently returned from California, in an unsuccessful attempt to find a gung fu teacher, so he was excited when he learned of the upcoming gung fu demo in his back yard. Jesse was impressed with what he saw, and vowed he was going to learn to move the same way. 20

Jesse has written that he started learning gung fu from Bruce in 1959 after seeing Bruce in a summer Seafair exhibition.21 But Bruce didn’t arrive in Seattle until September of 1959, long after the summer Seafair events were over. And his diary suggests that it wasn’t until January of the following year that he first met Jesse and began teaching him. His entry for Friday, January 8, 196022 reads:

To day after school, a negro came and ask me to teach him Kung Fu. He is a brown belt holder of judo and weighs 180 lb. However, I think he is kind of clumsy. If he practice under my instruction, I’m sure he can achieve distinction.

Two days later, on Sunday, he made another diary entry:

To day I went to the negro’s house and teach him a few tricks on Kung Fu and ask him not to use it on Chinese! Tonight I couldn’t go to sleep.

Jesse quickly realized that Bruce had some unique skills and started working out with him, initially one on one in Jesse’s apartment and at school and other odd locations when they could grab the time.23 Ruby didn’t like Bruce teaching non-Chinese, so they couldn’t practice at the restaurant.24

At that time, Bruce was still developing his own style, experimenting with techniques from other gung fu schools. He taught Jesse different ways to attack and defend so he could practice against them. As Jesse put it, “the only reason that I learned what I did was because at the time he needed a live dummy to train on.” A lot of the techniques were ones Bruce discarded, or simply filed away without passing them on when he later started teaching formal classes.25

Jesse also tells that when they first met, Bruce thought of his own skill level as being little more than an advanced beginner. He made trips up to Vancouver, B.C.’s Chinatown to buy books on different gung fu styles, then devoured them once back in Seattle; his dream was to learn the secrets of the masters of the various styles and combine them into a “super system.” For a while he was a strong believer in forms, but within a year changed his mind and discounted any system that emphasized forms.26

Bruce also trained a few others who were introduced by Jesse. The second student was Ed Hart, also a judo man and formidable street fighter, who roomed with Jesse. Howard Hall, another Edison student, and Pat Hooks, Skip Ellsworth and Charlie Woo, all judo men, soon joined. By then, the group had outgrown Jesse’s apartment.

By early February 1960 Bruce had met Taky Kimura through Jesse. Taky was a black belt in judo and Bruce spent hours working out with Taky in judo at the YMCA.27 After a while Bruce incorporated his new students into his demonstrations, but I believe that was after the April 1960 demo at the Seattle U smoker. By September LeRoy Garcia, whose wife went to Edison and had seen one of Bruce’s demos, had joined the group.

At first, it was Bruce and his fellow students exchanging martial arts techniques and working out together. According to Jim DeMile, a 225-pound, super heavyweight boxer in the Air Force who was also introduced by Jesse, Bruce was “a kid with some neat skills we wanted to learn,” and when they hung out after training together “we were just a bunch of guys having a good time and Bruce was just one of those guys.”28 Bruce no doubt learned a lot from them too, especially how techniques needed to be adjusted to deal with larger opponents than he was used to dealing with. Jesse also helped Bruce with adjustment problems in his new environment, including difficulty in speaking in front of others.29 But it was clear that they greatly valued Bruce’s superior skills in the martial arts. Although it was a mutual voyage of discovery, Bruce was the one driving the boat.

Bruce’s diary, February 6, 1960 Courtesy of the Bruce Lee Family Archive

Although Jesse eventually went his own way, he had tremendous respect for Bruce and referred to himself throughout his life as Bruce’s “first student.” He also unabashedly said that Bruce was “far ahead” of him, and that he “couldn’t hit Bruce if [he] had tried.” He went on to say that since Bruce was his “teacher,” he wouldn’t have tried anyway.30 Jim DeMile and Bruce had a falling-out early on, but he always spoke highly of Bruce’s unparalleled ability as a fighter.31

When the number of students Bruce was training grew larger, they started practicing in playfields and various other outdoor locations. By March of 1961 there were ten students who chipped in ten dollars each per month to rent some space in Chinatown.32 By May, with many of the students out of work, they had to give up the space; Bruce stopped teaching temporarily and took a part-time job outside of Ruby Chow’s to tide him over financially.33 When I joined the class, the group practiced in LeRoy Garcia’s back yard.

One diary entry gives an interesting insight into Bruce’s personality in his early years in Seattle. In early 1960 an entry mentions a “small scrap” he had had, noting that he had “better learn more patience and practice self-defence a little more.”34

WHILE HE WAS still at Edison, some months before I joined the class, Bruce was challenged by a karate man who also had a black belt in judo. 35 According to Jesse, the karate man had a reputation for picking fights with tough opponents, and winning.

It is not clear when the match took place, but I would guess it was around November of 1960. Jesse describes the fight as taking place after a demo Bruce and his students put on at Yesler Terrace gym which, from a poster in Jesse’s book, was on October 28, 1960. The karate man challenged Bruce after the demo, but Bruce declined after checking with his students to make sure they would not think any less of him. The pretext for the challenge was that the karate man had taken umbrage over a comment Bruce made about soft styles being better than hard styles. Bruce was referring to gung fu styles, but apparently the karate man thought Bruce was talking about karate. Over the ensuing days, the fellow became more and more obnoxious at school. Eventually Bruce’s patience ran out, and Jesse arranged for them to meet for a no-holds-barred, bare-knuckled match. 36

Bruce and some of his earliest students, Seattle, circa 1960 Standing left to right: Pat Hooks, Bruce, Ed Hart, Jesse Glover Kneeling left to right: Taky Kimura, Charlie Woo, Leroy Porter Courtesy of the Bruce Lee Family Archive

The match took place on a YMCA handball court. Present on Bruce’s side were Jesse, who acted as referee and Bruce’s second, Ed Hart, who acted as the timekeeper, Howard Hall and LeRoy Garcia. On the karate man’s side was Masafusa Kimura, the judoka who gave the demo with Bruce at the Seattle U smoker, and another student from Japan. The fight was supposed to go three two-minute rounds, with the winner being the one who won two of the three rounds. A round was won by knocking a man down or out. If someone was unable to continue, he lost. The challenger changed into his karate gi, complete with black belt. Bruce kept his street clothes but took off his shirt, shoes and socks.

Bruce waited for the challenger to make the first move, a snap front kick. Bruce swept it aside and attacked with a flurry of straight punches which in Jesse’s words “tore his opponent apart.” He finished with a kick to the face as the challenger dropped. Jesse went on to say, “When the guy hit the floor he didn’t move for a long time and we thought he was dead.” It turned out that Bruce had cracked his opponent’s skull around his eye and down into his cheekbone.

The entire encounter lasted something like eleven seconds, but when the challenger came to and asked how long it had lasted, Ed Hart felt bad and told him it had taken twice as long.37

When Bruce blocked the first kick, Jesse saw that it had brushed Bruce’s tank top undershirt, and thought “if the guy’s leg was a little longer or the kick was a little quicker that the fight might have taken a different path.” Shortly after that, according to Jesse, Bruce changed his tactics and decided it was better to carry the attack to an opponent rather than wait and counter.

Bruce did not hold grudges, however. The karate man later wanted to learn from Bruce. He wanted Bruce to give him private instructions, but Bruce told him he would have to join the class like everyone else.38