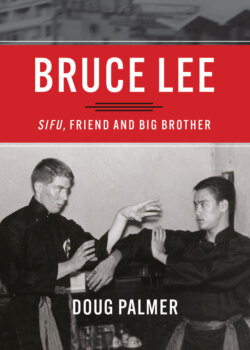

Читать книгу Bruce Lee: Sifu, Friend and Big Brother - Doug Palmer - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеBon Odori outside the Seattle Buddhist Temple, circa 1960s Courtesy of the Seattle Buddhist Temple Archives

CHAPTER 1

First Impressions

TOWARD THE END of the evening at a Seattle street fair during the summer of 1961, I felt a tap on my shoulder. I stopped and turned around. A young Asian man stood there, a pace or two away. The circulating crowd parted and flowed around us.

He leaned slightly back from the waist, his eyes hooded, a neutral expression on his face. “I heard you were looking for me,” he said.

I realized it was Bruce Lee. I had wanted to meet him after seeing him give a demonstration the week before, and had asked around to see if I could wangle an introduction. But I had heard nothing further until that evening.

The street fair, Bon Odori, sponsored by Seattle’s Japanese-American community, was one of a number of ethnic neighborhood events every summer leading up to Seafair, a weekend of hydroplane races and air shows. In those days, the races were sometimes overshadowed by the general bacchanalian atmosphere, where participants lugged coolers of beer to the shores of Lake Washington to watch.

Bon Odori featured Japanese folk dances on a blocked-off street in front of what was then the main Buddhist “church.” A milling crowd surrounded the dancers, watching or listening to the music blaring from loudspeakers, sampling kori (flavored shave ice) or fried noodles from booths set up on the fringes, or just checking out the action. A friend had asked me earlier in the evening if I was still interested in meeting Bruce. I told her that I was, then forgot about it as I enjoyed the atmosphere and chatted with other kids I knew.

Facing Bruce, I was initially nonplussed. On a subconscious level, I understood that his stance, although un-menacing and not overtly martial in appearance, was one from which he was prepared to react to whatever I did. Later, I realized it was a variation of the way he taught us to stand if faced by a potentially threatening situation. The idea was to be in a position where one could defend or counter-attack instantly, yet not appear to be hostile. It gave the appearance of alertness without concern, confidence and readiness without aggressive intent. As I later found, it could indeed project the desired attitude and prevent an undesired physical confrontation.

I took Bruce’s tone of voice to imply that I had been actively seeking him, perhaps for a challenge of some sort. In retrospect, I realized that in the world he came from, challenges were a part of life. Not knowing who I was or what I wanted, perhaps he thought that was a possibility.

I stuck out my hand and introduced myself. But in doing so, I purposely refrained from stepping closer to him. Rather, I leaned forward from the waist, extending my hand out for a long awkward handshake. I told him that I had seen his recent demonstration in Chinatown, and was interested in taking lessons.

He thought it over, then shrugged noncommittally and told me when they practiced. “Drop by sometime, check it out,” he said. “If you’re still interested, we’ll see.”

He melted back into the crowd. I had no idea where they practiced, or how I was going to get there. But I was ecstatic. One way or another, I would find a way to show up.

AT THE TIME, I knew next to nothing about Bruce Lee. Only his name and a first impression from the demo of Chinese martial arts I had seen the week before at another street fair, in Seattle’s Chinatown.

The demo was performed on a stage erected on one of the blocked-off streets by Bruce and three of his students. He called the martial art gung fu,1 a name I had never heard before.

I had just finished my junior year in high school. I had boxed since fifth grade, with a bout early on as a paperweight on a TV show called Madison Square Kindergarten. When I saw Bruce’s demonstration, my latest bout had been as part of a team that boxed the inmates at the state reformatory in Monroe. I had friends who practiced judo and had heard of karate—as a kid, I had even bought a bogus book on karate I’d seen advertised in the back of a comic book. But gung fu was a total unknown. At the time, I was unaware that it had a long history in China, or that it was then taught in Chinatowns across the U.S. only to Chinese.

When Bruce stood up there on the stage in his black gung fu uniform, he didn’t seem all that impressive at first. He looked rather slender, smaller than a high school running back, not even a welterweight. The three students who assisted in the demonstration, one black, one white, the third Asian, were all older and more imposing physically. But once Bruce moved, he commanded the stage.

When he moved, he literally exploded. His hands were just a blur; the power in his snapping fists was palpable as he missed his students’ noses by millimeters. As a boxer, I appreciated the moves he made with his hands. But the legs added a whole new dimension. The need to defend against kicks to the shin, knee or groin, or higher, signaled what seemed like a total fighting system. I was blown away.

Two other aspects of the demonstration also made an impression. One was the exotic grace of a praying mantis form he executed. It was quite unlike anything I had ever seen before. The second thing that stuck with me was the demonstration of chi sau, or sticking hands. Once he closed with his opponent and their wrists came in contact, he deflected all attempted blows and launched counterattacks with his eyes closed. I had never seen anything like that, either.

Much later, I found out that Bruce had given a demonstration over a year before I first saw him, at a function where I had boxed one night, but I never saw him then. The function was a Fight Night put on by a Seattle University fraternity in the university gym, just a few blocks from where Bruce was then living—a “smoker,” as such nights of boxing matches were then called. I was in the first of six bouts. According to the program, a copy of which someone showed me decades after Bruce died, the first six matches were followed by an event called “JACK MONREAN wrestles THE UNMASKED KNIGHT,” followed by another boxing match, and then by a “Chinese Boxing—Judo Demonstration” featuring Bruce against some judoka named Masafusa Kimura. After that was an intermission and the presentation of an “Ugly Man Plaque.”2

Since at that time I was only a sophomore in high school, barely fifteen years old and not yet driving, I was compelled to rush home right after my fight. As a consequence, I missed the Chinese boxing/judo match, if that’s what it was. Otherwise, I may have tried to hook up with Bruce even sooner than I did. Knowing Bruce (and his flair for showmanship), and since the program lists Ed Chow, the son of his landlord Ping and Ruby Chow, as being the commentator, I suspect the demonstration was a highly orchestrated affair highlighting the differences between the two disciplines, with Bruce showcasing his “Chinese boxing” to advantage. Since the judoka showed up several months later on the side of a karate man who challenged Bruce, perhaps he was offended by the experience.

In any event, it was to be more than a year after that before I was destined to run across him again, in 1961. Watching his powerful demonstration of gung fu at the street fair in Chinatown (now called the International District, or Seattle Chinatown/ID), I was mesmerized by the revelation of a whole new world. I vowed to myself that I would find a way to meet Bruce, and to learn from him this exotic new fighting system.

It didn’t take long to figure out a line of approach. The high school I attended, Garfield, was in Seattle’s Central Area. The student body was black, white and Asian, roughly a third each. I had a number of Chinese friends, and began to ask around. As it turned out, the younger brother of a classmate, Jacquie Kay, was taking lessons from Bruce. Jacquie was also a friend of Ruby Chow’s daughter, and Bruce spent a lot of time at Jacquie’s house, enjoying her mom’s home-cooked meals, talking with her father and drawing with her younger brother. I asked her to arrange an introduction, but heard nothing further until Bon Odori.

BRUCE LEE WAS a revolutionary. He revolutionized the martial arts world, and the way martial arts were portrayed in film. He overturned our stereotype of the Asian male (as being subservient and asexual), and brought an appreciation of the martial arts to a mainstream audience. His approach to the martial arts, and to life, influenced many people in other disciplines as well.

He also had a major influence on my life. That time I first saw him on that stage, I was sixteen. He was only four years older than I was—still 20. Close enough in age to be a friend, yet older enough to be a teacher (sifu) and, in many ways, like an older brother. Over the next decade, including a summer spent with him and his family in Hong Kong, I learned from him not only martial arts, but also many valuable life lessons that stuck with me and served me many times in good stead.

Program for Seattle University Smoker, April 8, 1960 Courtesy of David Tadman

By the time of his death his name had gained international recognition; afterwards, his influence mushroomed exponentially into a planet-wide phenomenon. He had the huge impact he did not just because he was a genius and a physical prodigy. His physical attributes are well-known, including preternatural speed and coordination, and exceptional strength for his size. Those attributes drew others to him, myself included. But he also possessed a formidable array of other qualities that were equally important: determination, self-discipline, persistence to the point of being a perfectionist, self-confidence, open-mindedness to new ideas and people, a willingness to share, a flair for showmanship, a subtle sense of humor that could be self-deprecating, a personal character that combined loyalty, a sense of dignity, and a respect for others.

Because he sometimes seemed larger than life, his subtlety and complexity could be overlooked. Some of his positive attributes at times verged on excess, the yang overwhelming any trace of yin. His self-confidence could come across as arrogance, his single-mindedness as self-absorption. But he was constantly assessing, taking stock, tinkering, not just with his martial arts but with his own character. In the end, he eliminated the strains that held him back, honing his arsenal of abilities to their maximum effect.

In his family’s words, when Bruce left Hong Kong for the States at the age of eighteen he was a “good to above average” martial artist, and when he returned four years later he manifested a “very special talent that is rarely found on this earth.”3 When I first met him he was a work in progress, and he was still evolving the last time I saw him nine months before he died.

In the chapters that follow, I hope to share the Bruce I knew, to let you see the qualities that made him the person he was, that made him so special not only to the people whose lives he touched directly, but to those around the world for whom he became an inspiration.

ENDNOTES

1 I spell gung fu with a “g” (rather than kung fu, the spelling most are familiar with) because that was how Bruce usually spelled it. That spelling also more closely represents its actual pronunciation than kung fu, a spelling which is an artifact of a particular system for romanizing spoken Mandarin, now on the wane. In pinyin, the romanization system used in China, it is spelled gongfu. Bruce was a native Cantonese speaker, but it so happens that the term gung fu is pronounced more or less the same in both Cantonese and Mandarin Chinese.

2 The smoker and demo were on April 8, 1960. See the program for the event, shown in this chapter.

3 Lee Siu Loong: Memories of the Dragon, by Bruce’s siblings and compiled by David Tadman, p. 6.