Читать книгу Bruce Lee: Sifu, Friend and Big Brother - Doug Palmer - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 3

ОглавлениеSeattle Classes

THE WEEK FOLLOWING my encounter with Bruce at Bon Odori, I hitched a ride to his gung fu class with Jacquie Kay’s younger brother, Roger. Roger was only thirteen, too young to drive, so his father took him to practice. By then, Bruce had graduated from Edison and started attending the University of Washington.

The classes then were held once or twice a week in LeRoy Garcia’s back yard. LeRoy lived on the east side of Lake Washington, the long lake along Seattle’s eastern border, in a log cabin he had assembled not long before. My memory is of an unpaved road or alley and a back yard that was more dirt than grass. He was a year or so older than Bruce; most of the other students were even older. LeRoy gave Bruce his first gun and taught him how to shoot it with some other students, but I don’t recall any mention of that.39

There were ten or twelve students altogether, among whom I recognized the three who had helped give the demonstration in Chinatown: Jesse Glover; Taky Kimura, a Japanese-American in his early thirties, as husky as Jesse; and Skip Ellsworth, a white guy who towered over them both.

Jesse impressed me immediately as a laconic, no-nonsense dude, tough and fast. Then only 26, to me (aged sixteen) he seemed a lot older. I knew he was a judo practitioner (by then a black belt40), and he had a tattoo on the back of one hand, as I recall between his thumb and index finger, which someone told me was a “pachuco” tattoo (a cross with dots signifying crimes committed, used by Chicano gangs in California). The tattoo made him seem even tougher. I never asked him about the tattoo, or heard anyone mention it. Since Jesse was (as far as I knew) a Seattleite, and there was no Chicano gang culture to speak of in Seattle then, I had my doubts. But in my mind it served to heighten his aura of quiet lethality.41

The rest of the class was also multi-racial: Jim DeMile (who was part Filipino), Ed Hart, Tak Miyabe, Charlie Woo and several others. Most had some background in the martial arts, mainly judo or boxing, before running across Bruce. At the time, I thought nothing about the racial makeup of the group. It was just like any class I attended at Garfield High School.

That first class I watched was a typical one. Everyone wore regular street clothes, albeit comfortable ones. Only two formalities were observed. The classes started and ended with a stylized salutation to Bruce as the teacher, which he returned. And during class he was addressed as Sifu (Teacher or Master), even though he was younger than all of the students except Roger.

For the salutation, the class formed up in several rows and faced Bruce. They bowed and then executed the salutation with a flourish, fists starting at their sides, hands rolling out in front as they stepped forward to a sort of ready stance, then stepping back and reversing the hands to the starting posture. Bruce executed the same salutation as he faced the class, without the bow. Brief, but elegant.

The salutation was followed by warm-up and stretching exercises, after which the class formed up into two lines facing each other and took turns practicing offensive and defensive moves. At some point, Bruce demonstrated a new technique, and then the class paired off to spar. Sparring was at full speed and power, with no gloves or protective gear. Students were expected to aim their punches and kicks to fall short of their target by an inch or so, in case the opponent failed to block in time. As I saw later, sometimes accidents happened.

The class also practiced a few minutes of what was called meditation. The students adopted the horse stance, with their hands cupped palms-up below the abdomen, eyes closed, and concentrated on breathing deeply, inflating the stomach rather than the chest. I remember Bruce saying later that such meditation technique could develop qi42 which in turn could produce great power in one’s strikes. But he also mentioned that that could take years of practice, if not decades. His punching power didn’t seem to depend on his qi, or at least any qi developed in that manner. To me, the few minutes of “meditation” seemed perfunctory, mildly intriguing but not particularly relevant to the rapid development of fighting skills.43

The class lasted about an hour and a half. When it ended, I was just as enthralled. I let Bruce know that I was still interested in joining the group. He nodded and said okay. At sixteen, I would be the youngest in the class next to Roger, and the only other student younger than Bruce.

THE DECISION TO join the class, however, required me to make an unpleasant choice.

The boxing lessons I had taken since grade school were held on Thursday evenings, the same night as the gung fu. They were conducted in the basement of a Congregational church on Seattle’s Capitol Hill by Walter Michael, whom his students and everyone else called Cap. The boxing classes were free, and open to anyone who walked in off the street, including street gangs who occasionally strolled in to scope it out and challenge some of the regulars.

Cap was a proficient martial artist in his own right, a former professional boxer. Although then nearly sixty, he could still handle any of his students with ease. His career spanned an era when professional boxers fought every week to earn a living. He also had quite a few tricks up his sleeve which were not sanctioned by the Marquis of Queensbury rules.

By then, boxing had been a huge part of my life for the past six years. Cap had been a mentor as well as a coach. I am indebted to him for first showing me how to take care of myself, for giving me the ability to distinguish competence from bluster, and the confidence to deal with dicey situations.

As a kid, my family had moved around a lot. I went to kindergarten in New Haven, first grade in Morristown, New Jersey, second and third grades and part of fourth in two different schools in the Bronx. Partway through the fourth grade we moved to Seattle and I finished fourth grade at one school, then switched for fifth grade to Madrona Elementary School when we bought a house in the Madrona neighborhood. Altogether, six different schools in six years. I perpetually seemed to be the new kid on the block.

In addition, since kids in New York started school earlier than New Jersey then, when we moved to the Bronx halfway through my first grade, I was jumped ahead into the second grade to be with kids my own age. When we moved to Seattle a few years later, we discovered that kids in my class were the same age as kids in New Jersey, rather than those in the Bronx. But it didn’t seem to make sense for me to drop back a grade at that point, so I stuck it out.

Then we moved to Madrona and to an elementary school that was half white and half black, with a few Asians thrown into the mix, a tougher school than I had attended before. I started the fifth grade there not only as the new kid on the block, but also a year or so younger (and smaller) than most of the other kids in the class.

A number of the kids boxed with Cap every Thursday. The frequent uprootings over the past few years had made me somewhat independent; but the need to constantly make new friends also made me conscious of ways to fit in to each new environment. I quickly determined that boxing would help on both scores, especially after getting thrown in a pricker bush one afternoon during an encounter with a classmate on the way home from school. I boxed every week through the end of my junior year of high school, developing a modicum of skill and gaining a lot of confidence, all of which I owed to Cap.

So it was a difficult decision to walk away from the Thursday boxing classes. In the end, however, the lure of Bruce’s gung fu won out. It seemed to be a more complete approach to the martial arts than boxing was, using all parts of the body as potential weapons, without any limits on the method for prevailing over one’s opponent in a real fight. And the insight into a whole new culture that it provided was a bonus.

I never lost my love for boxing, or my appreciation for its science. It did not seem at all odd to me when Bruce, a few years later, began to study films of some of the classic boxers, watching them over and over and mining them for practical insights to perfect his own approach to the martial arts. He would play films of Jack Dempsey, Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson, Archie Moore and Muhammad Ali, among others, and comment on the moves to me or my brother Mike, who was also a boxer. (I later met and observed Muhammad Ali during the course of two different business dealings. The first occasion was while I worked in a law firm in Tokyo, in the spring of 1972, about six months before the last time I saw Bruce. Ali was also an iconic figure, similar to Bruce in a number of ways. Although they never met, I think they would have gotten along.)

But at that point in my life, in the summer of 1961, I was drawn whole-heartedly into the world of gung fu.

ALTHOUGH I WAS impatient to get right into the fighting techniques, the first thing I had to learn in Bruce’s class was the salutation. Since it was as elaborate as an intricate dance step, it took a little time until I could execute it effortlessly. I also had to learn the bai jong (ready stance, with the right hand forward), so that I would have a platform to deliver the fighting techniques.

I was able to immediately participate in the various warm-up and strengthening exercises. As a skinny teenager who boxed reasonably well, I thought I was pretty flexible. I quickly realized, however, that I wasn’t particularly flexible in the ways that mattered for gung fu. The stretches were designed mainly to loosen and strengthen the ligaments and tendons behind the knees and at the elbows, very important for the snapping kicks and punches. Otherwise, one could easily hyper-extend and tear an elbow or knee ligament.

The main exercise to stretch the tendons behind the knees was to have a partner hold your outstretched leg at hip height with one hand and press down on your knee with the other, while you grabbed your calf and attempted to touch your forehead to your knee and hold it there without bending your leg. At first I couldn’t bring my head within a foot of my knee with the leg in that position, and even doing that made the tendons underneath the knee feel like they were being detached from the bones. But every night at home I would put each leg in turn up on the dining room table and bob my torso up and down with the leg straight out, until finally after several weeks I was able to touch my head to my knee and hold it there. At the time, I assumed the leg stretches were standard Wing Chun stretches, not realizing that Bruce himself had only developed such flexibility a year or so before.44

The other exercises I remember were also intended to limber us up. There were frog hops, where we would squat and proceed to hop like a frog around in a big circle; and an exercise where we would extend the arms straight out with the palms facing outwards and stretch the elbow joints, then raise the arms slowly up above our heads, interlock the fingers with the hands rotated upwards and stretch the elbows again. Other exercises included rotations of the neck in circles, and a form where we used the gung bou (“bow stance”) to pivot the hips and waist and upper body as far in each direction as we could while keeping the legs in the same position. We also used gung bou for a kicking exercise. We would swing the back leg up at full extension in a long arc to head height, then slap the opposite palm against the inside of the foot. Since we never used that particular kick in actual fighting techniques, presumably the exercise was mainly for the purpose of stretching the various tendons and ligaments around the hips.

Many sports use stretching exercises to warm up before a practice or a game, to minimize muscle pulls and other injuries. However, the gung fu exercises went beyond just warming up; they seemed designed to build up the strength and resilience and enhance the extension of the tendons and ligaments that anchored the muscles, rather than the muscles themselves. None of the exercises seemed aimed at building up muscle strength per se, or endurance. The unstated premise appeared to be that the muscles would take care of themselves if their foundation was strong.

Bruce’s own view of training changed over the years, and he later engaged in weight training and ran for endurance, but he didn’t over-do it to the extent that he sacrificed speed or flexibility.45 One thing that struck me when I returned to the school in Seattle that was directly descended from Bruce’s, run by Taky Kimura, several years after Bruce’s death, was the change in the warm-up and conditioning exercises. Some of the same ones were used, but in addition there was a heavy emphasis on push-ups and sit-ups.

AFTER THE EXTENSIVE warm-up and conditioning exercises, the classes in 1961 practiced techniques. For some of them, like the basic straight punch, we might practice them all facing Bruce (or one of the assistants who Bruce sometimes had lead the class). We would snap out a hundred straight punches, left-right, left-right, as fast as we could, starting with both fists held one above the other around the solar plexus, then punching with the upper fist straight out to full extension, bringing it back below the other fist, then punching with the second fist, and so on.

For most of the techniques, however, we formed into two lines, facing each other. If we were practicing kicks, the first person in one line would count out to ten in Cantonese and the whole line would kick to the count while the second line blocked the kick, after which the lines would switch offense and defense. There were two main kicks we practiced this way. One was the straight kick, delivered by the lead foot to the opponent’s groin, which the opponent blocked with a palm slap to the top of the midfoot. The second was the side kick, aimed at the opponent’s side, which the opponent blocked with a sweeping forearm. Although we aimed the kicks to land a few inches in front of the groin (in the case of the straight kick) or to the side (in the case of the side kick), it was important for the defenders to block sharply, both for the practice and in case of a miss.

The kicks could be aimed at other parts of the body—for instance, the straight kick could be aimed at the knee or shin—but we practiced kicking to the groin so that the defender could practice blocking. (A kick to the knee or shin couldn’t be blocked the same way; in combat, one needed to stay out of range, then close the distance before such a kick could be delivered.) There were also other kicks we learned (such as a kick using the rear foot, delivered to the knee, and a double kick which started with a straight kick to the groin, then rolled into a higher kick to the head when the groin kick was blocked, as well as others), but we didn’t practice them as much.

We also practiced hand techniques in two lines, each line alternating attack and defense. After each side had practiced both, those on one side would move down one place, so each person could work out with opponents of varying sizes and speeds and levels of ability.

The basic hand techniques we practiced this way almost every day were paak sau, laap sau and chaap choi/gwa choi. For techniques where the English translation was obvious, like for the side kick or straight punch, Bruce would use the English equivalent. But for the techniques where the English translation was not evident, such as the three hand techniques just mentioned, he would use the Cantonese terms, which we all learned.

Paak sau literally means “slapping hand.” With both rows standing in the basic Wing Chun stance, the attacker would use his left hand to slap his opponent’s leading (right) forearm aside and at the same time deliver a straight right punch over the opponent’s defense. The defender would block the straight punch with his open left hand.

Laap sau means “pulling hand.” As its name implies, the attacker uses his lead (right) hand to grab the opponent’s lead wrist, pulling him forward and off balance while simultaneously delivering a straight punch with his left hand. The defender would block with his left.

Chaap choi/gwa choi was a combination technique, a knuckle fist (chaap choi) delivered under the opponent’s lead arm to the ribs, followed by a back fist (gwa choi) to the jaw or temple when the opponent blocked the first blow. The defender would block the knuckle fist with a sweep of his right arm, which the attacker would then slap and trap while delivering the back fist.

After practicing the basic techniques, Bruce would often demonstrate a new technique, or a form, which we would then practice. Sometimes he would give a talk on the philosophical or mental aspects of gung fu, and how it could be applied in practice.

We also learned basic chi sau (“sticking hand”) techniques, a form of practice which is found only in Wing Chun and a few other schools, where the two opponents adopt complementary stances with their wrists and forearms literally touching each other’s as they move their arms in a set pattern from which they launch attacks. The form of chi sau we learned had been modified by Bruce from the way it was practiced in Hong Kong, with more forward pressure;46 and when I returned to the Seattle school in later years it had been de-emphasized.47

Toward the end of the class we would pair up and spar, either using chi sau or free style, and the various techniques we had learned. After that, we would line up and end with the salutation again. Once class was over, we no longer had to address Bruce as Sifu.

ALTHOUGH I DIDN’T realize it at the time, the make-up of Bruce’s class was unique in the history of gung fu. As I discovered later, non-Chinese were not taught in Hong Kong. Likewise in Hawaii, a melting pot in every other respect, only Chinese were taught—not even other Asians were admitted to the gung fu schools. As far as I know, the same was then generally true in Chinatowns across the continental U.S. Certainly Ruby Chow let Bruce know that she did not approve of his teaching non-Chinese.

A few gung fu instructors undoubtedly taught non-Chinese before Bruce did. For example, James Lee in Oakland (no relation), who later became a close friend of Bruce’s and collaborated with Bruce when he began to develop Jeet Kune Do, privately taught a Caucasian friend some of the Chinese martial arts beginning in 1958 or so, including “iron hand” breaking techniques. I met James and his friend when Bruce and I visited James on the way back from Hong Kong at the end of summer 1963. James may also have taught a few other non-Chinese around the same time.

Other gung fu teachers are also said to have taught non-Chinese before Bruce even arrived in the States. This may well be so. But from all I saw and heard, that would have certainly been the exception and not the rule. And I would wager that no other gung fu teacher up to then had taught so many non-Chinese as openly as Bruce did. Ethnic background was literally not a factor when aspiring students asked to join his class.

The fact that Bruce openly taught non-Chinese was greeted with shock and incredulity when we gave a demonstration in Vancouver, B.C. Chinatown sometime in the summer of 1962, and later when Bruce used me to give a demonstration at a gung fu school in Honolulu on the way back from Hong Kong in 1963. Chinese students at Yale, whom I met when I went off to college, confirmed that their gung fu schools only taught Chinese. And when Bruce took me along to watch him work out with his teacher in Hong Kong, I had to pretend that I was just a friend from the States, who knew nothing about gung fu. Even Bruce, out of respect, did not want his teacher to know that he had been teaching non-Chinese.

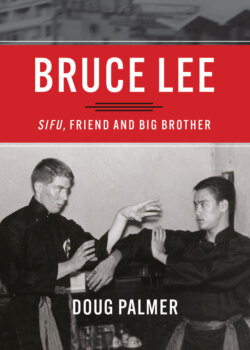

Early class of students, author and Jesse flanking Bruce, Seattle, circa 1962 Courtesy of the Bruce Lee Family Archive

A year or so after we got back from Hong Kong, in Oakland, Bruce was challenged by another gung fu practitioner, Wong Jack Man,48 according to one version because the Chinese community was aghast that Bruce had opened up a school and admitted non-Chinese as students. Wong apparently denied that was the reason for the match, claiming his challenge was actually a response to a general challenge Bruce had given to local gung fu practitioners during a demo in San Francisco Chinatown. He also later claimed that his own school was the first one in San Francisco Chinatown to operate with “open doors”—that although most of his students were Chinese, not all of them were. I can’t say for certain, but I believe Wong had not yet even started his own school at that point. In any event, if Bruce was not the first to teach gung fu to non-Chinese, he was certainly the first one who did it on the scale he did; and the first one who reached out so widely and openly beyond the Chinese community. In Bruce’s case, the vast majority of his students were non-Chinese, and he made it a mission to proselytize to any audience he could get in front of.

The actual match with Wong Jack Man is still the subject of controversy as to almost every detail, from the reason it was held to the way it unfolded and its ultimate outcome. I have heard the story from Bruce, and I believe his version, for reasons I will explain in more detail in a later chapter.

The fact that Bruce himself was part Caucasian and by some accounts had problems of his own being fully-accepted as a gung fu student in Hong Kong may have had something to do with his attitude about teaching to anybody without regard to race. But as was obvious from the make-up of the class I joined, he literally did not care about a person’s racial or economic background, or sex. If someone wanted to learn gung fu and was willing to work hard at it, Bruce was willing to teach them. The fact that with girls it afforded a good excuse to get up close and personal was perhaps an extra plus. Indeed, Bruce got to know his future wife, Linda Emery, when she took lessons.

The racial composition of Bruce’s gung fu class was like the high school I attended, so I didn’t think much about that. But the students, nearly all older than Bruce, with a wide array of martial arts and rough-and-tumble backgrounds, were all drawn to Bruce because of his obvious mastery and practical approach. There were black, Chinese, Japanese and white students with judo backgrounds (like Jesse Glover, Bruce’s first student), and others (like Jim DeMile) with boxing backgrounds. Some were simply tough dudes who knew a lot about street fighting and recognized an approach that was more efficient and effective.

For Bruce’s part, he seemed to revel in testing himself against guys who had been around the block and were bigger and rougher-looking than he was. He was confident and didn’t hesitate to spar or engage in other physical contests. Although he was only 135 pounds or so then, I saw him arm-wrestle (and beat) a tough black kid who weighed over 225 pounds and who could easily bench-press his own weight. He also did a one-handed push-up with the same kid on his back. (He once did a three-finger push-up with me on his back, but I only weighed 170 pounds or so back then.)

At the time, it all seemed normal, but even then I had a glimmer that I was part of something special, that I was learning from someone who epitomized the best in the martial arts, not just in terms of technique or physical ability, but in overall approach.

OVER THE YEARS the location of Bruce’s gung fu classes changed a number of times. Before I joined the class, Bruce and his first students practiced wherever they could—in public parks and playing fields and gymnasiums. Not too long after I joined, the class was relocated from LeRoy Garcia’s back yard to a parking garage underneath a medical building on First Hill, across the street from where Bruce lived and worked, at Ruby Chow’s Restaurant.

The parking area took up the entire ground level of the structure, which covered a half block or so. The multi-storied building over the parking area protected us from rain, but there were no walls. The building rested on thick columns spread throughout the parking area, like a longhouse on stilts, so in the wintertime it was as cold as the rest of the outdoors. At the times we practiced, on Thursday evenings and weekends, there usually weren’t too many cars parked in the garage, so we had plenty of room to spread out. And the price was right—I am confident that Bruce did not pay any rent for the use of the space. Ruby Chow’s Restaurant, as well as the building with the parking garage where we practiced, has long since been torn down and redeveloped. The parking garage is now part of the Swedish Hospital complex.

Practice in Blue Cross Parking Garage, Seattle, circa late 1961/early 1962 Courtesy of David Tadman

Sometime during the next year the class moved again, to a rundown space in Seattle’s Chinatown where a Szechuan noodleshop is today. The indoor space was marginally warmer than the open-air garage and anything but spacious. If Bruce paid any rent, it probably wasn’t much. Later, the class moved to a basement location a few blocks away. (Underneath Chinatown—and the part that used to be “Japan Town” before World War II, and had been repopulated mainly with Japanese after the war—was a “city” of basements, many of which were interconnected with tunnels. One time in high school I was with a group of Japanese-American friends who had a party in a basement under a Japanese restaurant, drinking beer and watching inappropriate movies. I guess we had been making too much noise, because the cops showed up and began to shine flashlights through the front door of the restaurant. We panicked and dispersed through the tunnels, leaving one friend who was too drunk to walk hidden behind a pile of empty shoyu (soy sauce) barrels. I emerged a block or so away from the restaurant in a different building, unmolested by the police.)

Practice in Blue Cross Parking Garage, Seattle, circa late 1961/early 1962 Courtesy of David Tadman

I believe the basement in Chinatown was when he started calling his school the Jun Fan Gung Fu Institute (Jun Fan being his given name in Chinese).