Читать книгу "How Awesome Is This Place!" (Genesis 28:17) My Years at the Oakland Cathedral, 1967-1986 - E. Donald Osuna - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеOn that momentous afternoon, the three of us were glued to the rectory television monitor. An American astronaut was stepping onto the moon and announcing a giant leap for mankind. Science and technology had wedded and were giving birth — right there in our living room — to a new age.

Just as memorable was Father Jim Keeley’s comment at the end of the telecast: Gazing out the window at the silver sphere with an earthling now prancing about its surface, the young priest prophesied, “Wait until the poets get a hold of this!”

That was July 20, 1969.

Earlier in the decade, a similar landmark event had altered the course of church history. In 1962, the recently elected pope, like the visionary American president, had set his sights on a far-off target. President Kennedy took man to the Moon; Pope John XXIII brought the Catholic Church back to earth. For too long, the pontiff concluded, the bark of Peter had skirted the realm of human affairs like a satellite, detached, remote and locked into its own orbit. The ship had become obsolete; it was time for a return to earthly origins. Once grounded in its native soil, the Church could once again reclaim its pristine identity: that of a disciple and servant of the Lord Jesus Christ who alone had ascended into the heavens!

The trajectory was earthward; the propellant for reentry was to be the sacred liturgy. To achieve this, Pope John had convened the Second Vatican Council which immediately engineered the reform of the Roman Rite, thereby taking aim, as one colleague put it, “for the jugular.” Nothing is as sacred to the Church as its rituals which cradle and nurse so jealously its ancient creeds. At worship, believers experience what it means to be Catholic. For them, sacramental celebrations and especially Sunday Mass reveal and express the very essence of religion: the Word of God and Christian Tradition. So, in order to bring the Church around, the Pope and the bishops of the Second Vatican Council had to subject the sacred liturgy to review, revision and renewal.

The results were revolutionary. Out went the Latin, the ancient voice of a buried empire. Henceforth the sacred mysteries were to be proclaimed in the tongues of the people. Rubrics and ceremonials were restored to their original simplicity, eliminating centuries-old “accretions.” Flexibility replaced the rigid and stylized rubrics of the Council of Trent (1545–63). Waves of changes and revisions began inundating beleaguered pastors.

Some critics claimed that the liturgical reforms reduced the sacramental structures to bloodless skeletons. But others considered it profoundly insightful of the Council to provide simple frameworks for local churches to adapt and enhance with local cultural and religious traditions. No doubt about it: Pope John, who was ready to embrace everyone he met, wanted the Roman Rite to be equally as catholic — welcoming, encompassing, incorporating into its worshiping embrace the diverse and distinctive heritages of the human family.

The pioneers had done the deed. Were there to be any poets?

*****

Floyd L. Begin, installed as the first Bishop of Oakland, attended every session of the Council and dutifully espoused the spirit and letter of its decrees. When the three-year conclave ended, he determined that his new diocese would be the first American see to implement its reforms. So the first thing the Cleveland native did upon returning from Rome was to hire Robert Rambusch of New York to refurbish his cathedral church. St. Francis de Sales was to be gutted and completely renovated to conform to the new liturgical norms — notwithstanding the history or sensibilities of the local parish community in Oakland, California.

The bishop’s unilateral decision to reshape the diocese’s mother church without local consent or consultation was bold, dramatic and provocative. But it was the quickest way to cast in concrete his commitment to implement the mandates of the Second Vatican Council. He too could aim for the jugular!

When it was dedicated on February 4, 1967, the gleaming edifice at the corner of Grove Street and San Pablo Avenue lit up the heart of Oakland’s inner city. Ironically, it illuminated the gloom of the surrounding landscape: the dismal Greyhound bus depot across the street, the halfway house for convicted felons down the block, the decaying hotel and flophouses along the avenue. Its empty nave highlighted the equally forlorn and forsaken congregation: seniors from the surrounding high-rises and the residents of the low-income family dwellings nestled between apartment buildings and commercial storefronts. (The neighborhood had once been a prosperous enclave for Irish and Italian immigrants. But the war years had caused it to mutate into a haven for out-of-state job seekers and military-base personnel. The parish school, once an academy for the offspring of the original settlers, now tutored poor Hispanic children from the neighborhood and African-American youths from the nearby ghetto.) Why should these local folks attend the inauguration of a resplendent reconstruction that in their eyes represented a mausoleum commemorating the death of a treasured past?

If anyone had reason to be bitter, disgruntled and irate, it was Monsignor Richard “Pinkie” O’Donnell, pastor since 1942 of St. Francis de Sales parish and its first rector when Rome in 1962 selected it as the cathedral church of the newly created Diocese of Oakland.

“Let me tell you something, Father Osuna,” he intoned shortly after I was assigned as his assistant, “I was serving Mass as an altar boy in this very church when the earthquake of nineteen hundred six shook this place to its foundation. The parish pulled through that tragedy just fine. But it will never survive what this bishop from Ohio has done to it. He didn’t just gut the place, he has torn the heart out of the people!”

That was not all. Evidently, Bishop Begin had plundered the parish coffers as well. Rumor had it that in order to pay for most of the renovation, he expropriated all but $27,000 of the half million that the good monsignor had accumulated in savings over his twenty-five-year tenure!

O’Donnell was right. The “defacing” of the ancient shrine had completely demoralized the locals. There was a time, he pointed out, when they could point to the images of their ancestors who had posed as models for the host of saints that populated walls and ceilings. Now there was no one up there. All had been obliterated by a blanket of cream-colored paint! The transcendent stained-glass window of the Crucifixion above the high altar was gone, boarded over by layers of redwood paneling! The white marble altar, with its terraced columns and Gothic niches, had been dismantled and replaced by a bishop’s throne! A masterpiece of renovation perfectly suited to the new liturgical norms? Perhaps, but to Pinkie and his people it represented an arid arena and a shameful sepulcher.

But events would soon prove Monsignor O’Donnell wrong. The people of St. Francis would recover. The arid arena would become a Mecca for pilgrims from the Bay Area and around the world. In time, thousands would flock to the Oakland Cathedral to experience the “creative liturgies” that began to enliven and rejuvenate the flagging inner-city parish. These vibrant weekly liturgies forged worshipers into a praying and caring community. Over time, the liturgies inspired and impelled them to reach out to others in Christian fellowship and social action. And it was to Sunday Eucharist that they returned each week to celebrate their identity and their work, and to be spiritually revitalized for the week ahead. In short, worship became the engine that sustained personal devotion and fostered expanded ministry, thus exemplifying the Council’s definition of liturgy as “the source and summit of Christian spirituality.” This memoir is the story of my life in that remarkable parish. As priest and artistic director, I spent nineteen years contributing to its creation and growing in its nurturing embrace. With countless others I experienced a vision, which, like that of Jacob at the shrine of Bethel, shaped my life forever.

When Jacob awoke from his sleep he exclaimed, “Truly, the Lord is in this spot, although I did not know it!” In solemn wonder he cried out: “How awesome is this place! This is none other than the house of God. This is the gateway to heaven!”

(Genesis 28:16.)

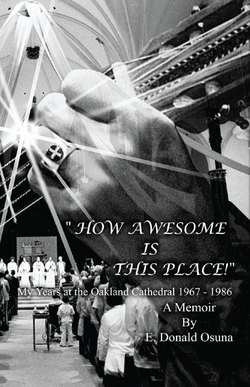

Original St. Francis de Sales interior, remodeled in 1967 (lower)

Seasonal liturgical design by Patricia Walsh