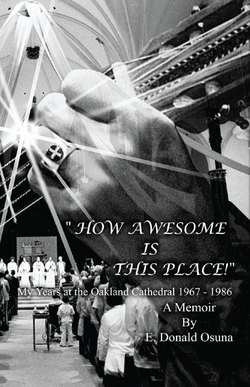

Читать книгу "How Awesome Is This Place!" (Genesis 28:17) My Years at the Oakland Cathedral, 1967-1986 - E. Donald Osuna - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prelude: Before It Happened

ОглавлениеTheatre, music and art had been as much a part of my life as my desire to be a priest. As a boy soprano I sang solos from the choir loft at St. Louis Bertrand church in east Oakland. Monsignor Silva insisted that I become an altar boy and sent me untrained on to the sanctuary at the age of eight. Sister Kevin Marie, O.P., principal of the school, encouraged me to design artwork for the classroom and persuaded my mother to have me enrolled for piano lessons.

When I entered the seminary in Mexico City after the sixth grade, the rector recognized my musical potential and arranged for organ lessons. [Both my mother and father were from Mexico and agreed to have me study there, knowing that countless relatives would take good care of the youngest of their brood of ten children.]

After I transferred to St. Joseph’s minor seminary in California, Father John Olivier, S.S., dean of studies and director of music, mentored me in the art of choral conducting and appointed me seminary choir director. Under his supportive wing I teamed up with Michael Kenny (the future bishop of Juneau, Alaska) to form K.O. Productions. Together we wrote original musicals (California or Bust), mounted and performed in Broadway plays (Kismet, Harvey) and tried our hand at Shakespearean theatre (Henry IV, The Merchant of Venice).

At St. Patrick’s major seminary, where the focus was on the study of theology, the arts became strictly a personal pursuit. A group of fellow seminarians and I established the “Art Forum,” where we encouraged each other to draw and paint, make stained-glass windows, delve into sculpture and even try our hand at bookbinding.

Always needing a musical outlet, I started a glee club. We performed classics such as Benjamin Britten’s A Ceremony of Carols and St. Nicolas Cantata and gave concerts of American and international folk songs. I also was compelled to start a “gloom club” for those unfortunate souls who were unable to pass the audition for the glee club. (To my delight, some of these aspiring singers, like Dan Derry and Jimmy Tonna, actually learned to carry a tune!) Once a month I picked up my guitar and, along with a couple of my Mexican-American classmates, serenaded visiting families and friends with musica ranchera. These were satisfying enterprises that kept my creative juices flowing.

During summer breaks, I enrolled in undergraduate courses at Stanford University and Holy Names College in order to reinforce my natural musical and artistic skills with an academic foundation.

One would expect that, once ordained, a twenty-six-year-old priest would have no time for the arts. Not so, in my case. One year into my first assignment at St. Jarlath parish in Oakland, the order came to implement the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. This would involve revamping the sacred liturgy with its unique blend of all the arts — visual, musical, dramatic. Unlike some of my older colleagues, I was ready and well prepared — and eager — to tackle the challenge.

When the time came for “turning the altar around” in Advent of 1965, our pastor, Father Denis Kelly, took off for Ireland and left his three assistants to do the “turning.” It was the beginning of an exciting and challenging task: designing a new altar, supervising its construction, and explaining to the congregation why the priest was facing them and saying Mass in English.

Things got even more exciting when Bishop Begin asked me to put together the music for the dedication of his newly remodeled cathedral. I composed and arranged much of the music, assembled and rehearsed a large choir and instrumental ensemble from parishes and local colleges, and got ready for the big event.

The ceremonies on February 4, 1967 were spectacular, especially the music that featured strings, harp, organ, flute, brass, chimes and tympani accompanying chorus and congregation. I remember the expression on my Irish pastor’s face: He simply could not fathom how his young assistant had found the time and the resources to come up with such a jaw-dropping performance — with a harp no less!

The bishop was also impressed. A few months after the cathedral dedication, he appointed me Diocesan Director of Music and transferred me to St. Francis de Sales Cathedral as associate pastor with a mandate to create for the diocese a “model liturgy.”

*****

In the summer of 1968, while I was on leave, Bishop Begin installed Father Michael Lucid, aged thirty-nine, as cathedral rector; he also assigned Father James Keeley, thirty-seven, as assistant pastor. Both were Irish-American, native San Franciscans and former high school teachers — credentials that appealed to the older clergy who were balking at the recent changes in the Church. But Lucid and Keeley were also students of history, keeping abreast of current events and very much in tune with the agenda of the Vatican Council. This delighted the progressives who were counting on the new team to bring from its storeroom “both the old with the new” (Matthew 13:52). No one would be disappointed. Even the seventy-five-year-old Monsignor O’Donnell would be charmed by the young churchmen who gently but resolutely took over the helm of his floundering parish.

Personally, my association with Mike and Jim was a turning point in my life. It made me reconsider my intended departure from the active ministry.

How had I come to that decision?

After six months in Pinkie O’Donnell’s morbidly depressing rectory, I was on the verge of emotional collapse. The resentful monsignor refused to honor the bishop’s mandate empowering me to take charge of the cathedral worship services. To that purpose I had previously contracted with my friend from seminary days, John L. McDonnell, Jr., to establish a cathedral choir. John was a probate lawyer and a musician whose forte and delight, along with the practice of law, was directing choirs. I very much respected his musical talent and his taste for excellence. (I also enjoyed spending time with him, his brilliant wife, Loretta, and their three growing toddlers at their home on Trestle Glen.) I was sure that John’s experience and my vision would result in a successful collaboration. Together, I felt certain, we could create a model liturgy for the diocese as the bishop had requested. The frustrated Monsignor O’Donnell, however, refused to provide the funds we needed to proceed, indignantly maintaining that all reserves had been “confiscated” by the Chancery.

Compounding the rectory situation was the general malaise that afflicted both Church and country in 1968. The U.S. had turned into a social battlefield: the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the civil rights movement, the escalation of the Vietnam War, student uprisings and militant protests. Within the Catholic population a growing polarization over Vatican II reforms was exacerbated by Pope Paul VI’s denunciation of all forms of artificial birth control in his famous encyclical Humanae Vitae. As a result, clergy, religious and laity became as unsettled as the beleaguered citizenry.

During those discouraging months, I found myself facing a personal question that had plagued me for a long time: Should I continue in a career that required one to be “all things to all men,” or should I make use of my God-given talents and pursue the life of an artist and musician? Unable to resolve the conflict, I asked for a leave of absence and quietly left for New York City. There I spent a month with my brother Jess, a professional actor of stage and screen who had successfully mastered the realm of dramatic arts. Thanks to his hospitable and gracious mentoring, I feasted on an extravagant menu of cultural offerings until my artistic hunger had been sated and my soul satisfied. Revived, refreshed and reassured in spirit, I decided to quit the priesthood and pursue a career in music and the performing arts.

When I returned to Oakland, the only person I confided my secret to was my classmate and best friend, Father Tony Valdivia. Sheepishly I asked him to please call my parents and inform them of my decision. (I was too ashamed and afraid to do it myself.) This was more than he was prepared to deal with. Instead, he drove me to the Cathedral and declared, “There’s a brand-new administration in place here. Give Lucid and Keeley a try. If it doesn’t work out after two weeks, I’ll call your mother!”

Then he escorted me upstairs to my suite (the one next to Monsignor O’Donnell’s). Once in my room, he began to unpack my personal belongings that were still in sealed boxes — lots of them. As each carton became empty he tossed it out the third-floor window onto the pavement below. That created quite a ruckus and roused the napping prelate next door.

Suddenly, there he was — Pinkie O’Donnell — standing in the threshold.

“Oh, it’s only you, Osuna!” he roared. “For a minute there I thought we were having another earthquake!”