Читать книгу "How Awesome Is This Place!" (Genesis 28:17) My Years at the Oakland Cathedral, 1967-1986 - E. Donald Osuna - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One: Of Pioneers and Poets

ОглавлениеPinkie’s sarcasm and personal animosity towards me were soon offset by my new boss’s openness and no-nonsense attitude. Mike Lucid was not only broadminded and friendly — he was downright ecumenical. He even allowed me to get a dog — and a female at that! No doubt, he figured that a puppy would help the process of humanizing a household of celibates — which is exactly what Muffin did. One of the fondest images engraved forever in my memory is that of the four of us driving to a local restaurant for dinner on Tuesday evenings with Muffin comfortably enthroned on Pinkie’s lap.

Despite the aged pastor’s gradual mellowing, Pinkie continued to chide me. “What time does the circus start?” he asked me one Sunday morning as we passed on the stairway. A week later, however, I remember him remarking after one of our children’s liturgies: “That was really nice!” Monsignor Richard O’Donnell died on May 23, 1971. His close friend and executor, Msgr. Charlie Hackel, asked me to perform at the funeral a selection he labeled as a “particularly appropriate anthem.” The song’s concluding lyric was: “The record shows I took the blows and did it my way.”

*****

Mike Lucid, our new boss, had a keen mind that sized up situations in a flash and an organizational skill that zeroed in on possible solutions. These gifts became evident at our first staff meeting.

“This parish has many needs and few resources. We will have to agree on a set of priorities. What do you think our most important undertaking should be?”

I suggested the parish school, because it was the only thing currently meeting an urgent need in the community. Moreover, the Sisters of the Holy Names who had staffed the school for eighty years were an influential and respected presence in the neighborhood.

“Education is important,” Keeley concurred, “but I think that as a church, our first priority should be to teach our people to pray.”

“Agreed,” interjected Lucid. “Worship first, school second.”

“Osuna,” he continued, “you will take charge of all liturgical services, and Keeley will oversee all religious education programs. Now, I want both of you to report back to me next Tuesday on what strategies must be implemented and how much money will be needed to operate our targeted ministries. Agreed?”

Priorities, strategies, finances? This was sounding too good to be true! Was I really being invited to develop a liturgical program that would engage all my artistic interests? What a fabulous prospect: to use one’s musical and artistic skills and adapt them to Catholic worship where all the arts naturally converge! The intended move to New York was off!

I immediately contacted John McDonnell and asked him how much he thought we needed to maintain an effective music program, including paid personnel and a large volunteer choir. “Five hundred dollars ($500) a month,” was his response, adding, “that’s the minimum!”

The following Tuesday, I gave my brief report: “In terms of strategy, I need to feel assured that I can spend as much time as needed on liturgical and artistic matters, and that when there is a conflict, others will cover the phones and doorbells.”

“Agreed,” Lucid confirmed. “Now, how much money do you need?”

“Five hundred dollars a month.”

Lucid’s face turned as white as the cathedral ceiling.

“Five hundred dollars? Do you realize that is one Sunday’s collection — twenty-five percent of our monthly income?”

Keeley spoke up, uttering another one of his memorable sayings, “I believe that the definition of a priority is putting your money where your mouth is!”

“Agreed.”

A few days later, Lucid asked to talk to me in private. “I understand that the diocesan music committee, of which you are the director, has arranged for the installation of a new pipe organ for the cathedral. I also understand that it will cost thirty-five thousand dollars. Is that right?” I nodded. “Well, the bishop has ordered me to pay for it out of our savings! However, there are only twenty-seven thousand dollars in that account. Furthermore, the school budget will require this year a parish subsidy of twenty-five thousand. I’m afraid that I have to ask you to postpone the purchase of the new organ.”

Reluctantly I agreed, but I knew we were in deep trouble! Not having a pipe organ meant settling for an electronic (God forgive the concept!) replacement! There goes the quality of our music program! How can one properly accompany congregational and choral singing without the “king of instruments”?

Time to consult with John McDonnell again! The only way to ensure musical integrity, the wise attorney counseled, was to engage a permanent instrumental ensemble: strings, brass, piano (“At least that’s an authentic keyboard!”), and additional musicians as the nature of the music required. It was a brilliant solution — and financially feasible. The addition of the live instruments would reinforce, legitimize and perhaps even drown out the sound of the “electronic bastard”!

As it turned out, the musicians we hired were mostly college music majors who were as proficient in popular musical idioms as they were in the classical repertory. (Among these extraordinary talents were Julie Meirstin on violin/piano and Bob Athayde on brass; the couple, who met at the cathedral, eventually married and are the parents of a trio of musicians, including Juliana Athayde, concertmaster of the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra of New York.) As a result of such versatility, we chose music from a wide variety of styles. And because the people in the pews were from such disparate musical cultures, we programmed a blend of selections that at some point during the service would resonate in each praying soul, young and old, native and foreign, of whatever musical persuasion. Thus was born the “Oakland Cathedral Sound.”

By 1971, even Time Magazine took notice:

One church has discovered that a variety of music can attract worshipers. Nine years ago when it was designated the cathedral for the new Roman Catholic diocese of Oakland, Calif., the inner-city parish of St. Francis de Sales included little more than a commercial section of downtown. But one young curate, Father Don Osuna, has since been wisely encouraged to improve the liturgy. Now, twice each Sunday, the music runs the scale between such unlikely extremes as Gregorian chant and rock. On one recent Sunday, the mixture embraced both Bach’s Air for the G-String and Amazing Grace. On another included a Haydn trio, Bob Dylan’s The Times, They Are A Changing’ and Luther’s A Mighty Fortress Is Our God. Worshipers come from all over the Bay Area. The Sunday collection, once a mere $100, is now up to $800 a week. (“Troubadours for God,” May 24, 1971)

Our eclectic approach was anything but haphazard or arbitrary. It was a result of lessons learned early on in our programming efforts and our determination to tailor the music to the cultural background of a multicultural group of worshipers.

When John McDonnell and I put together our first Sunday liturgy for the sparse, reticent and what we considered “old church” congregation, we selected all traditional hymns, with the exception of one contemporary religious “folk song” by Joe Wise, “Take Our Bread.” It called for a guitar, which in those days was considered a strictly secular instrument and unsuitable in church. To render the piece more palatable we had the keyboards and strings play along with the guitar. To our surprise, the people loved it. The simplicity of the melody and the quaint sonority of the guitar had an instant appeal that complemented the traditional hymns. It sounded “right.”

This prompted us to take a closer look at the divergent tastes of our people and find music that reflected and reinforced their cultural sensibilities. In time, we began introducing other musical idioms such as Negro spirituals, gospel selections and hymns in Spanish to reflect the diverse ethnic makeup of the growing congregation. The inclusive nature of the musical menu set the crowd at ease and bolstered an ever stronger active participation.

The secret of success, we discovered, lay in programming the various musical styles in a logical and appropriate sequence. Every liturgy, for example, began with a classical prelude performed by the full choir and ensemble, e.g. Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” a polyphonic motet or a setting by a modern composer. The entrance song would be a traditional congregational hymn accompanied by keyboards and brass: “O God of Loveliness,” “How Great Thou Art.” This combination created a palpable connection to the past and provided a feeling of security and comfort. In contrast, the recessional would generally feature a modern hymn or a rousing Gospel anthem: “Pass It On,” “Ain’t Got Time to Die.” This prepared the rejuvenated worshipers to confront with resolve the world they were about to reenter. Within the Mass itself, we programmed contemporary compositions from the library of popular and religious folk songs: “Psalm 42: As the Deer Longs,” “The Prayer of St. Francis.” The entire ensemble reinforced the natural ebb and flow of the liturgy with its inner dynamic of climaxes (the Gospel Acclamation, the Great Amen, and Communion Song) and meditative movements (after the First Reading and following the Communion Song).

I was convinced that this kind of stylistic blending reflected the cultural psyche of the typical American audience, which seems to be more at home with a musical amalgam than a sustained dose of a single type of music. It is a phenomenon that every successful variety show producer knows so well. Virtually every television spectacular and special presentation invariably features a well-packaged mix of opera and the classics, Broadway musicals, popular, jazz and any other repertory that will appeal to the consumers whom the sponsors intend to capture. And so, artistic directors typically put together a “product” containing something for everyone. This is the American way. It works. It was only logical for an American liturgist to baptize it. After all, the people who watch Saturday Night Special are the same souls sitting in our pews on Sunday morning.

The Vatican Council’s document on the sacred liturgy confirms this view. It states that in ministering to the faithful, “pastors must promote liturgical participation taking into account their age and condition, their way of life, and standard of religious culture.” This norm was dubbed the “pastoral principle.” The U.S. Bishops’ Committee on the Liturgy defined it as the judgment that must be made in a particular situation and in concrete circumstances. “Does music in the celebration enable these people to express their faith, in this place, in this age, in this culture?” (Music in Catholic Worship, #39). As liturgists and musicians, we at the Oakland Cathedral adapted this pastoral principle to the profile of our people.

Our music program, however, was always at the service of the Word of God — the two were inseparably wedded. The music announced, reinforced and recalled throughout the celebration the biblical theme contained in the readings of the day. At the beginning of the liturgy, for example, the prelude and entrance song introduced the theme to be proclaimed in the Scriptures and elaborated upon later by the homilist. The Offertory Song immediately following the sermon served as a commentary upon or a response to the entire Liturgy of the Word. And finally the Communion and Closing Songs echoed the gospel theme as the worshipers shared the Body and Blood of Christ and took the Word with them into their homes, offices, schools and marketplaces.

My friend Father Tony Valdivia, always the insightful critic, once put it this way: “Your selection of music is a homily in itself.”

*****

The “eclectics” are a very “catholic” phenomenon borrowing tastefully from a variety of sources and blending the selections in a patchwork effect which is aesthetically pleasing and rewarding. Campus worship particularly reflects this kind of approach and the fine choir and ensemble at the Oakland Cathedral is its epitome.

Ken Meltz, “Musical Models for the Eighties,” Pastoral Music (April–May 1984)

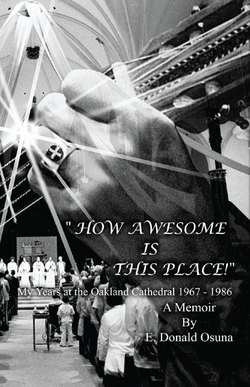

Don Osuna and members of the Cathedral Ensemble

John L. McDonnell, Jr. conducting the Cathedral Choir