Читать книгу The Mezentian Gate - E. Eddison R. - Страница 15

III NIGRA SYLVA, WHERE THE DEVILS DANCE

ОглавлениеTHAT night Prince Aktor startled out of his first sleep from an evil dream that had in it nought of reasonable correspondence with things of daily life but, in an immediacy of pure undeterminable fear, horror and loss that beat down all his sense to deadness, as with a thunder of monstrous wings, hurled him from sleep to waking with teeth a-chatter, limbs trembling, and the breath choking in his throat. Soon as his hand would obey him, he struck a light and lay sweating with the bedclothes huddled about his ears, while he watched the candle-flame burn down almost to blueness then up again, and the slow strokes of midnight told twelve. After a tittle, he blew it out and disposed himself to sleep; but sleep, standing iron-eyed in the darkness beside his bed, withstood all wooing. At length he lighted the candle once more; rose; lighted the lamps on their pedestals of steatite and porphyry; and stood for a minute, naked as he was from bed, before the great mirror that was on the wall between the lamps, as if to sure himself of his continuing bodily presence and verity. Nor was there any unsufficientness apparent in the looking-glass image: of a man in his twenty-third year, slender and sinewy of build, well strengthened and of noble bearing, dark-brown hair, somewhat swart of skin, his face well featured, smooth shaved in the Akkama fashion, big-nosed, lips full and pleasant, and having a delicateness and a certain proudness and a certain want of resolution in their curves, well-set ears, bushy eyebrows, blue eyes with dark lashes of an almost feminine curve and longness.

Getting on his nightgown he brimmed himself a goblet of red wine from the flagon on the table at the bed-head, drank it, filled again, and this time drained the cup at one draught. ‘Pah!’ he said. ‘In sleep a man’s reason lieth drugged, and these womanish fears and scruples, that our complete mind would laugh and away with, unman us at their pleasure.’ He went to the window and threw back the curtains: stood looking out a minute: then, as if night had too many eyes, extinguished the lamps and dressed hastily by moonlight, and so to the window again, pausing in the way to pour out a third cup of wine and, that being quaffed down, a fourth, which being but two parts filled left the flagon empty. Round and above him, as he leaned out now on the sill of the open window, the night listened, warm and still; wall, gable and buttress silver and black under the moonshine, and the sky about the moon suffused with a radiancy of violet light that misted the stars. Aktor said in himself, ‘Desire without action is poison. Who said that, he was a wise man.’ As though the unseasonable mildness of this calm, unclouded March midnight had breathed suddenly a frozen air about him, he shivered, and in the same instant there dropped into that pool of silence the marvel of a woman’s voice singing, light and bodiless, with a wildness in its rhythms and with every syllable clean and sharp like the tinkle of broken icicles falling:

‘Where, without the region earth,

Glacier and icefall take their birth,

Where dead cold congeals at night

The wind-carv’d cornices diamond-white,

Till those unnumbered streams whose flood

To the mountain is instead of blood

Seal’d in icy bed do lie,

And still’d is day’s artillery,

Near the frost-star’d midnight’s dome

The oread keeps her untim’d home.

From which high if she down stray,

On th’ world’s great stage to sport and play,

There most she maketh her game and glee

To harry mankind’s obliquity.’

So singing, she passed directly below him, in the inky shadow of the wall. A lilting, scorning voice it was, with overtones in it of a tragical music as from muted strings, stone-moving but as out of a stone-cold heart: a voice to send tricklings down the spine as when the night-raven calls, or the whistler shrill, whose call is a fore-tasting of doom. And now, coming out into clear moonlight, she turned about and looked up at his window. He saw her eyes, like an animal’s eyes, throw back the glitter of the moon. Then she resumed her way, still singing, toward the northerly corner of the courtyard where an archway led to a cloistered walk which went to the Queen’s garden. Aktor stood for a short moment as if in doubt; then, his heart beating thicker, undid his door, fumbled his way down the stone staircase swift as he might in the dark, and so out and followed her.

The garden gate stood open, and a few steps within it he overtook her. ‘You are a night-walker, it would seem, and in strange places.’

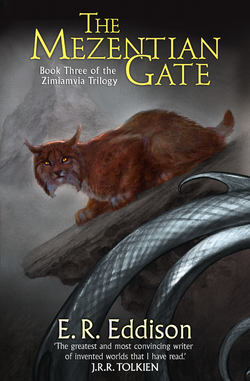

‘So much is plain,’ said she, and her lynx-like eyes looked at him.

‘Know you who this is that do speak to you?’

‘O yes. Prince by right in your own land, till your own land put you out; and thereafter prince here, and but by courtesy. Which is much like egg without the meat: fair outsides, but small weight and smaller profit. I’ve heard some unbitted tongues say: “princox”.’

‘You are a bold little she-cat,’ he said. Again a shivering took him, bred of some bite in the air. ‘There is frost in this garden.’

‘Is there? Your honour were wiser leave it and go to bed, then.’

‘You must first do me this kindness, mistress. Bring me to the old man your grandsire.’

‘At this time of night?’

‘There is a thing I must ask him.’

‘You are a great asker.’

‘What do you mean?’ he said, as might a boy caught unawares by some uncloaking of his mind he had safely supposed well hid.

Anthea bared her teeth. ‘Do you not wish you had my art, to see in the dark?’ Then, with a shrug: ‘I heard him tell you, this afternoon, he had no answer to questions of yours.’

‘I cannot sleep,’ said Aktor, ‘for want of his answer.’

‘There is always the choice to stay awake.’

‘Will you bring me to him.’

‘No.’

‘Tell me where he sleeps, then, and I will seek him out.’

Anthea laughed at the moon. ‘Hearken how these mortals will ask and ask! But I am not your nurse, to weary myself with parroting of No, no, no, when a pettish child screams for the nightshade-berry. You shall have it, though it poison you. Wait here till I inform him, if so he may deign to come to you.’

The prince saw her depart. As a silver birch-tree of the mountains, if it might, should walk, so walked she under the moon. And the moon, or she so walking, or the wine that was in his veins, or the thunder of his inward thought, wrought in him to think: ‘Why blame myself? Am I untrue to my friend and well-doer and dispenser of all my good, if I seek unturningly the good that seems to my incensed brain main good indeed? She is to him but an engine to breed kings to follow him. With this son bred, why, it hath long been apparent and manifest he is through with her: the pure unadulterate high perfection of all that is or ever shall be, is to him but a commodity unheeded hath served his turn. By God, what cares he for me either? That have held her today, thank the Gods (if any Gods there were, save the grand Devil perhaps in Hell that now, if flesh were or spirit were, which is in great doubt, riveth and rendeth my flesh and spirit), in my arms, albeit but for an instant only, albeit she renegued and rejected me, to know that, flesh by flesh, she must be mine to eternity? God! No, but to necessity: eternity is a trash-name. But this is now; and until my death or hers. And what of him? That, by my soul (damn my soul: for there is no soul, but only the animal spirits; and they unknown, save as the brief substance of a dream or a candle burning, that lives but and dies but in her): what surety have I (God damn me) that he meaneth not to sell me to the supplanter (I loathe him to the gallows) sits in my father’s seat? Smooth words and sweet predicaments: I am in a mist. Come sight but for a lightning-flash, ’tis folly and madness to trust aught but sight. Seeing’s believing. God or Hell, both unbelievable, ’tis time to believe whichever will show me firm ground indeed.’ He was in a muck sweat. And now, looking at that statue as an enemy, and in the ineluctable grip of indignation and love, each with the frenzy of other doubled upon it by desire, he began to say within himself: ‘Female Beast! Wisely was that done of men’s folly, to fain you a goddess. You, who devour their brains: who ganch them on your hook by their dearest flesh till they are ready to do the abominablest treasons so only they may come at the filthy anodyne you offer them, that is a lesser death in the tasting, that breaks their will and their manhood and, being tasted, leaves them sucked dry of all save shame and emptiness only and sickness of heart. Come to life, now. Move. Turn your false lightless lustful eyes here, that you may see how your method works with me. Would they were right cockatrice’s eyes, should look me dead, turn me to a stone, as you are stone: to nothing, as you are nothing.’