Читать книгу Sir David de Villiers Graaff - Ebbe Dommisse - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Preface

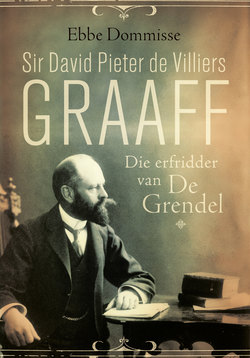

ОглавлениеThis biography is the first to plot the life of Sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff in full. No comprehensive biography has yet been written about him, other than an honours thesis that mainly concerns itself with Graaff’s role in the Cape Town city council.1 Indeed, few studies have been undertaken about South Africans generally who may be regarded as the second line of political leaders, but who nevertheless had a significant impact. This is in sharp contrast to the great amount of published material available about people deemed as members of the front line of political leadership, like the biographies and other works on Louis Botha, Jan Smuts, D.F. Malan, P.W. Botha, F.W. de Klerk, Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki.

Graaff’s life story is a fascinating piece of history, especially because it encompasses the very eventful era at the time of South Africa’s unification. However, Graaff – an influential politician – was also a highly successful businessman, an entrepreneur who, as the pioneer of cold storage in South Africa, amassed a fortune from frozen meat and other food. Graaff’s role as businessman in politics in itself presents material for a separate study, since the role of the businessman-cum-politician in South African history has hardly been explored. Another interesting feature of his life story is the rare hereditary baronetcy he was honoured with, linked to the splendid farm De Grendel.

The research about this versatile and complex pioneer began after his grandson, Sir David Graaff, expressed to the author his desire that a book be written about his grandfather. Members of the Graaff family co-operated with the research, but there was no interference or restrictions of any kind – only the request that the account be as true and accurate as possible.

Some of the quotations in this biography were originally from Afrikaans or Dutch sources, but were translated for the benefit of readers who do not understand those languages. The imperial monetary system and weights and measures of that time are also used throughout, as the metric system was only introduced in South Africa in the middle of the 20th century.

During the course of the research on Graaff, which yielded a much more comprehensive corpus of work than initially thought, Alex Mouton, professor of history at the University of South Africa, delivered a stimulating inaugural address about the value of biography for historiography. He argued that without biographical studies of parliamentary politicians it would be difficult to understand the pre-1994 South Africa.2 Mouton said:

The crucial contribution of biography is that it humanises history as it reflects life – its heroism, nobility, endurance, folly, ignorance, weaknesses and brutality. For the British biographer Michael Holroyd, biographers are the messengers of the dead calling to us out of the past, asking to be heard, remembered and understood.3 As G.M. Trevelyan hauntingly summarised it, “… the poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that once, on this earth, once on this familiar ground walked other men and women, as actual as we are today, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own passions, but now all gone, one generation vanishing into another, gone as utterly as we ourselves shall shortly be gone, like ghosts at cockcrow”.4

The purpose of documenting Graaff’s life story was to write an interpretative, critical biography, using an approach that follows the disciplinary conventions of the historian rather than the techniques of the literary author or commemorative biographer. Furthermore, the aim was to portray Graaff in his time, not to give an account of the man and the time in which he lived and worked. This is the same approach followed by W.K. Hancock in his extensive biography of Smuts.5 At the same time, writing such a biography requires, as Lytton Strachey recognised, that it should not be a mere collection of facts in chronological order ending in a “dull, lifeless chronicle”.6 Although there is only a relatively small amount of archival material about Graaff’s personal life, an attempt was made to portray the mosaic of his life.

The biography was submitted as a doctoral thesis at the University of Stellenbosch, where Albert Grundlingh, professor of history, provided valuable advice and critical insight.

Others who assisted with the research and who deserve special mention are Melanie Geustyn of the National Library in Cape Town; Jaco van der Merwe of the Archives in Cape Town; Charmaine McClean of the De Beers Archives in Kimberley; Liesl du Preez and Gustav Hendrich, researchers in Pretoria and Cape Town; the staff of the Bodleian Library and Rhodes House in Oxford and the National Archives, College of Arms and British Library in London; staff of the university libraries of Stellenbosch and Cape Town; Chris Theron and Brett Moore of The Graaffs Trust in Cape Town; and Pieter Cronjé of the Cape Town city council. Also acknowledged with gratitude are Richard Rosenthal and family for their permission to consult Eric Rosenthal’s unpublished manuscript about Imperial Cold Storage.

Lastly, a special word of thanks to my wife, Daléne, for her love, patience and constant interest in a project that took a year or two more than initially intended.

EBBE DOMMISSE

Cape Town 2011