Читать книгу Sir David de Villiers Graaff - Ebbe Dommisse - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеFrom herdboy to on high

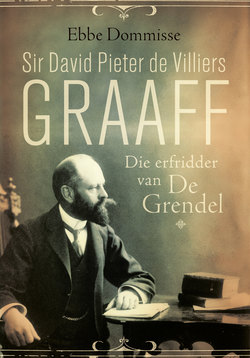

Only a few months after its birth in 1910, the Union of South Africa demonstrated its newly acquired independent status from the former colonial power, Britain, in earnest for the first time. It occurred at the 1911 session of Parliament led by a South African member of cabinet on whom the British king had recently conferred a hereditary title: Sir David Pieter de Villiers Graaff, Baronet of Cape Town.

This demonstration of South Africanism happened under the wings of the unlikely portfolio of post and telegraphs, one of the two positions Graaff held in the first Union cabinet. At issue was the Shipping Ring, a combination of British shipping lines that through collusion and a rebate system on their postal and freight ships maintained a stranglehold on the Cape sea route. Graaff, a confidant of the first premier, General Louis Botha, was determined to bring that to an end. It required a new Postal Act, but also all the business acumen that distinguished Graaff, the pioneer of cold storage in South Africa, in a business career that had started at the tender age of 11.

A journalist who observed from the press gallery what was transpiring in the House of Assembly early in 1911 described how the young nation led by Graaff raised its hackles and declared war against the Shipping Ring with its rebates, dictates and unfair tariffs. The Union of South Africa, a recent amalgamation of four provinces with a troubled history, gave a mighty roar – a roar to indicate it wanted to be in charge of its own territory.1

Graaff, the commander of a crusade, had a triumphant reception in Parliament, where he received support across party lines. His actions would still be recalled years later. In newspaper articles it was declared there were only two businessmen in South Africa at the time who would be able to handle the complicated negotiations, Graaff and John William Jagger, a Cape wholesaler.

Graaff’s performance became a parliamentary highlight in a versatile career in which he made his mark on the South African landscape in more than one respect. Not only as an influential politician – subsequently he served as minister of finance and high commissioner in London – but also as an affluent businessman and successful farmer. Moreover, his life story presents a picture of the relatively small network of imminent personalities who determined South African history before and after unification. As a friend and confidant of the first two premiers of the unified South Africa, Louis Botha and Jan Smuts, Graaff had intimate access to and at times participated in the decisions the two Boer generals had to take about various important issues.

A significant aspect of his career was his ability to move among different spheres, almost different worlds. His complex career – as capitalist politician, as entrepreneur and innovator, as a Cape Afrikaner who had to move between Boer sympathy and British imperial forces, as initially a poor farm boy who eventually had a key position in decisive moments – casts light on the political, social and cultural life of this era in South Africa’s history. His life story presents a historical perspective of a specific time and contributes to greater knowledge and understanding of the past.2

Indeed, the “new South Africa” that began in 1994 rests on much older foundations – foundations to which people like Graaff made a contribution. His exceptional success as a businessman alone is relevant to the conditions of share options and transfers of 21st-century South Africa. Besides, he was influential in politics, initially at local government level, where he greatly contributed to the modernisation of the city of Cape Town. This influence extended to national level – few top business people in South Africa have exercised as much influence at the highest level of national government as Graaff. This facet of his career also casts light on the relationship between businessman and politician, an aspect of historiography that has enjoyed little attention in South Africa.

Graaff’s emergence from a poor family on a farm in Villiersdorp, where he was a herdboy with little schooling, is a story of exceptional drive and persistence – from herdboy to on high. The young Dawie Graaff was only 11 when he left the farm where he was born in the Overberg for Cape Town to work in the butchery of a relative, Jacobus Arnoldus Combrinck. The Afrikaans-speaking country boy, who had probably only passed standard 3 at school in his home town and then attended an evening school in Cape Town, showed at an early age that he had an exceptional brain for business. As a young entrepreneur, he took over the management of the business Combrinck & Co. from his “old uncle” Combrinck when he was just 18 years old. He extended his innovations in the field of refrigeration and new developments in the meat industry with an extensive distribution network for frozen products, with the help of refrigerator carriages he bought for transport on the growing South African rail network. He made such rapid progress that within a few years he was regarded as the pioneer of cold storage in South Africa. The large-scale refrigeration of meat, fruit and other products, unprecedented in the land of his birth, made him his fortune. His style of entrepreneurship differed markedly from that of the mining magnates who made their fortunes from the country’s mineral resources, like gold and diamonds, at the time.

Graaff’s South African Cold Storage Company, which developed out of Combrinck & Co., provided meat for the British troops during the Anglo-Boer War, but also to the people in the interior and the concentration camps. During the war, probably as a result of his sympathy with the Boers – including a relative who was a Cape rebel – Graaff was placed under house arrest in Cape Town, where draconian measures were in force in terms of the martial law imposed in the Cape Colony by the British forces.

Graaff’s experiences present an informative view of the difficult position of Cape Afrikaners caught between two extremes: on the one hand, loyalty to the British Empire, of which the Cape Colony was part, and on the other, faithfulness to their Afrikaans origins and blood ties with the burghers of the republics in the north. Among his intimate republican connections were two of the most famous Boer generals, Louis Botha and Jan Smuts.

Graaff was one of a number of prominent businessmen who played an important part in politics in the decades before and after unification, both in the old Cape Parliament and after 1910 in the South African Parliament. Among the leading figures were Cecil John Rhodes, Sir James Sivewright, John William Jagger, Richard Stuttaford and Sammy Marks. Earlier, in the 19th century, business life and politics in the Cape had been dominated by English-speaking people, until the Afrikaner Bond of Onze Jan Hofmeyr began to have an impact. The entrepreneurs who founded sophisticated industrial and financial companies at that stage were mainly of British origin or Eastern European Jews; the Afrikaners in the Boland concentrated on viticulture and crop farming.3

South African-born Graaff was an exception to the trend that the remarkable economic progress that South Africa made in the 20th century was initially the result of English-speaking entrepreneurs who came to live in South Africa. Michael O’Dowd describes how these English-speakers had brought to South Africa all the skills needed for industrial development, from financial and business acumen to the skills of mineworkers, artisans and railway workers. Thus a home-grown entrepreneurship was developed, the greatest asset a country could have. These entrepreneurs helped to ensure that South Africa, like the United States, did not remain an exploited colony, deteriorating to a state of backwardness owing to a government that nationalised or tried to control industries.4

Graaff was such an entrepreneur, albeit from an Afrikaner background. His ascent through the business world occurred some time before the accelerated mobilisation of Afrikaner capital following from the Eerste Ekonomiese Volkskongres (First Economic Congress of the Nation) of 1939.5 This was coupled with an active policy of secondary industrialisation (like the development of Iscor, Eskom, Sasol and Foskor). According to O’Dowd, the credit is due to Afrikaners for this, as most English-speakers opposed it.6

The entrepreneur Graaff did not limit himself to South Africa, however, but also expanded his business interests internationally to Europe, South America and South Africa’s neighbouring countries. As a successful young businessman, he demonstrated a singular sense of social responsibility at an early age. As a 23-year-old, he was elected as a Cape Town city councillor and at the age of 32 he became mayor of the Mother City. During his time as councillor, but especially as mayor from 1890 to 1892, the city was heavily modernised. He played a decisive role in bringing electricity to Cape Town, and the first power plant was named after him. Motivated by his pride as a citizen, Graaff played a leading role in making the dirty city a much more inhabitable place.

His achievements on a local level led to service on a higher level. As a supporter of the Afrikaner Bond, he was elected as a member of the Upper House of the Cape Parliament. As was the case with many other Cape Afrikaners, there followed a breach with the then premier, the mining magnate Cecil John Rhodes, as a result of the Jameson Raid in 1895. In 1897 Graaff retired from politics temporarily to pay more attention to his business interests. A full decade passed before Graaff, by that time one of the wealthiest businessmen in Cape Town, returned to politics in 1908 as a member of John X. Merriman’s Cape cabinet.

In the newly formed South African Party (SAP) Graaff and F.S. Malan, as high-profile Cape Afrikaners, played a decisive role in the election of General Louis Botha as first premier of the Union. This resulted in an estrangement with Merriman, the other candidate, who denounced Graaff and Malan as “Judases”. Graaff’s support helped the SAP in the Cape against the financial assistance of the Randlords for the imperialistically-minded Unionists of Dr Leander Starr Jameson. Graaff, who was elected as member of the House of Assembly for Namaqualand, served in the Botha cabinet in various portfolios, lastly as finance minister. To date, he and his brother, Sir Jacobus Graaff, who also became a member of cabinet, have been the only two brothers ever to have served in a South African cabinet together.

Graaff was a bachelor when the British honorary titles were awarded to South Africans shortly after unification. Initially reluctant, he received a baronetcy, a hereditary title, in 1911, probably because it was thought he would not have any heirs. Two years later the 53-year-old bachelor, then a member of the nobility, married a clergyman’s daughter 30 years his junior – after initial opposition from her mother due to the age difference.

Graaff suffered health problems after a serious operation in 1912, and in 1916 he retired from cabinet. He remained a friend and confidant of General Louis Botha, with whom he attended the Versailles peace summit in 1919 at the end of World War I. At that stage he was playing an important part in the transfer of the lucrative diamond fields of South West Africa (Namibia) to South African interests, led by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer.

After his retirement as Member of Parliament in 1920 Graaff devoted his full attention to his business interests. He became chairman of Imperial Cold Storage, which went through cyclical ups and downs until the Great Depression. Among his other interests were The Graaffs Trust, a company formed to handle the assets of the Graaff family, and Milnerton Estates, at present the parent company of The Graaffs Trust and the source of large land purchases in the Tygerberg.

His three sons grew up on De Grendel just outside Cape Town, where he had a stud farm. Two heirs of his title, his eldest son, De Villiers, who would become the country’s longest-serving leader of the opposition, and his grandson, David, also followed political careers – resulting in three generations of Graaffs who served in Parliament.

Graaff also became known as a generous benefactor – in education among other things; he financed a school that was named in his honour, the De Villiers Graaff High School in Villiersdorp, his home town. Upon his death during the Great Depression, his will provided for the creation of a baronetcy fund, which ensured that his hereditary title, linked to De Grendel, would exist until the tenth generation as long as there was an heir. Given Graaff’s contribution to the development and order of things in South Africa, the baronetcy, a rare honorary title of which only two remained in South Africa in 2009, is nevertheless of far lesser importance than the political role and the singular entrepreneurship that distinguished the Villiersdorp farm boy.