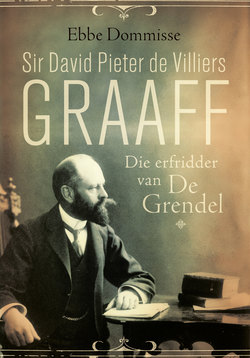

Читать книгу Sir David de Villiers Graaff - Ebbe Dommisse - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 2

ОглавлениеThe farmhand and the

pretty farmer’s daughter

The Graaffs have a long history in South Africa.

Those members of the family who came to South Africa mainly emigrated from Germany. Like most other German-speakers, they soon started speaking Dutch, at that stage the language generally spoken in the Cape after Jan van Riebeeck founded a refreshment station for the Dutch East India Company (DEIC) in 1652. For many German-speakers it was easy to switch to Dutch, especially for those from northern Germany, whose home language, Plat Deutsch, was closely related to Dutch.

The first Graaff, Johan Jürgen Gräff, came to South Africa from Dorn-Assenheim. He made the voyage from Germany on the Borsselen in 1761 as a soldier in the employ of the DEIC. Fourteen years later the second Graaff followed, the ancestor of Sir David Graaff’s South African family. He was Johannes Jacobus Graff (1754–1804), who came from Reidlingen, a town near Baden in the Black Forest. This Graff, as the surname was initially spelled before it was eventually changed to Graaff, was born on 21 July 1754 and came to Cape Town in 1775 as a 21-year-old soldier in the service of the DEIC. He married Anna Catharina Wolmarans in 1779 and then worked as a carpenter and painter.1

As a carpenter he became known for a singular heritage: the impressive pulpit of the Groote Kerk in Cape Town. Graaff – also named Jan Jacob Graaf in some documents (like those of the Dutch Reformed Church) – crafted the wooden pulpit resting on two lions following a design by the sculptor Anton Anreith. The pulpit of Indian wood is one of three designed by Anreith – the other two are in the Lutheran Church in Strand Street, Cape Town, and the Rhenish Church in Stellenbosch. The Groote Kerk paid £400 for the pulpit, of which Anreith received £180 and Graaff £220. It replaced the pulpit damaged by beetle infestations that stood in the original church building, inaugurated in 1704. Graaff finished the pulpit in 18 months and it was inaugurated on 29 November 1789.2 Over a century later, Sir David Graaff would serve as an elder in the Groote Kerk and was known as a benefactor of the oldest congregation in the country, where his ancestor’s handiwork still drew admiration.

A grandson of the Graaff ancestor, Petrus Norbertus Johannes Graaff, generally known as Nort (probably derived from the High German Norbert, with its Latin variant Norbertus), was David Graaff’s father. In some documents he was named Novbertus, supposedly due to confusion between an “r” and a “v” in old documents.

When Nort was born on 15 July 1823, the Cape was under British rule. The Dutch rule, initially ended by the first British occupation in 1795, was resumed from 1803–1806 under the Batavian Republic, but after that the Cape became a British Crown colony, a situation that would continue until unification in 1910.

In the middle of the 19th century Nort lived on a farm in the district of Villiersdorp, on the Franschhoek Mountains. On this farm one of the most beautiful love stories from the Overberg would play out – the romance between David Graaff’s parents, the story of the farmhand who won the heart of the pretty young farmer’s daughter.

Nort was appointed as a farmhand at the cattle post of the eminent farmer of Radyn, Pieter Hendrik de Villiers, founder of Villiersdorp. The cattle post, Wolfhuiskloof, lay at the foot of Wolfberg, one of the mountains surrounding Villiersdorp. Sometimes it was known as Wolfieskloof; the later owners simply named the farm Wolfkloof. A few kilometres away, and within viewing distance across the fertile valley, lay Radyn, the pioneer farm that initially belonged to a free burgher of Polish descent, Jan Jurgen Radyn. He had arrived in the Cape in 1707 as a soldier of the DEIC and made a wagon road that reached to the current Villiersdorp valley. The farm, retaining Radyn’s name, was taken over in 1836 by Pieter Hendrik de Villiers, a descendant of the Huguenots who farmed in the district of Stellenbosch, until he moved to what was then an outlying area. According to his descendant Sir De Villiers Graaff (a grandson), he was called Pieter Silwermyn, a nickname he acquired because of attempts to mine silver on the slopes of the Simonsberg on his earlier farm, De Goede Hoop, near Stellenbosch.3

Pieter Hendrik de Villiers, a respected man who also served as field cornet of the district, had the land of Radyn surveyed and subdivided with a view to founding a town, which came about in 1844, the founding date of what would later be known as Villiersdorp. Of Bo-Radyn he eventually only retained 293 morgen. The Cape Dutch homestead, with its exceptional unsymmetrical “H” shape, was declared a historic monument in 1975. On the pilastered front gable with its triangular pediment two dates appeared, 1777 and 1836, apparently indicating alterations.4

Various new residents settled adjacent to Bo-Radyn in the new town, initially called Akkedisdorp. However, permission was obtained from the colonial governor, Sir Peregrine Maitland, to name the town after its founder, P.H. de Villiers, and since then it has been called Villiersdorp.

De Villiers was the most prominent leader and government official of the area after his appointment as field cornet of the ward Boven Rivier Zonder End. He was married to Catharina Helena Minnaar and they had five children, two sons and three daughters. One of the daughters was Anna Elizabeth – the pretty Annie, with whom Nort fell in love; as the Wolfhuiskloof herdboy, he had to come to Bo-Radyn every now and then. It seems Annie also soon started to have feelings for the young, handsome Nort.

The owner of what would later be a show fruit farm, however, did not take kindly to the young man’s interest in his daughter. Therefore, Field Cornet De Villiers forbade the bywoner boy from coming to the farm. However, love is unstoppable. Nort would sneak through the bushes and shrubs, ostensibly to help Annie with the washing at the mill stream. For that he earned himself a thorough hiding from Sir De Villiers Graaff, according to a tale told to Cobus le Roux, a subsequent owner of Bo-Radyn.5

One of the love letters Nort had sent to Annie by messenger was later found by his son Dawie in a secret drawer of a large armoire, an heirloom that came from Wolfhuiskloof and after some roaming ended up on the Graaff family farm, De Grendel, in Tygerberg in the Cape. Even as a young man, Dawie, later Sir David, had an interest in beautiful furniture, carpets and paintings. For this purpose he often consulted a good friend, Dr. Lawrence Herman. Herman bought the ornate wardrobe for Graaff at an auction; it still stands in the manor.

One day, Graaff was admiring the walnut piece with its silver fittings, pulling out drawers and pushing buttons and hinges. To his amazement, one of the panels moved, swung open and a number of drawers appeared. In the third drawer there were a set of dentures and the title deeds of the old family farm Silwermyn. He discovered that the armoire had belonged to his own family while they resided in Stellenbosch.

Another drawer contained a letter to Mijn Schat (my darling). It was his father’s own passionate plea to pretty Annie of Radyn. The letter read thus:

“No longer can I endure our clandestine meetings. No longer can I humiliate myself by pleading with your parents. In their eyes I am not worthy of their daughter. No longer am I prepared to be silenced by your father’s arrogance and haughty demeanour when addressing me. You must decide now whether to come with me, as we have so often planned, or that we shall part.

“I shall be under the big oak tree at the end of the avenue at nine o’clock. Come warmly clad, as the journey will take two hours to reach the home of Tante Maria. If you are not there at ten o’clock, I shall depart alone. Do not fail me, my darling.”6

How the letter ended up in the drawer remains a mystery. Perhaps Annie or her mother hid it there. The conclusion of the saga, according to family tradition, was, however, that at the age of 23 Nort eloped with his young mistress. Legend has it that the young Graaff kidnapped the De Villiers daughter on horseback.7

On 2 May 1846 Nort and the 18-year-old Annie were married by a magistrate in Franschhoek. Upon their arrival back in Villiersdorp, father-in-law De Villiers finally consented to the marriage, but insisted that male offspring should get the name De Villiers as well. Hence the merger of the Huguenot name De Villiers with the German-Dutch Graaff that would distinguish later generations.

At a time when large families were the order of the day, five sons and four daughters were born from the marriage of Nort and Annie,8 who went to live a simple life at Wolfhuiskloof, about four kilometres from Villiersdorp. The sixth of the nine children, David Pieter de Villiers Graaff, was born on 30 March 1859. He and his eldest brother, Pieter Hendrik de Villiers Graaff (born in 1848), acquired the middle name of De Villiers – but not the other three Graaff brothers, Johannes Jacobus Arnoldus (Jan or John, 1854), Jacobus Arnoldus Combrinck (Kobie or Koos, 1863) and Pieter Christiaan (1866).

The name De Villiers would continue in the case of David Graaff’s three sons, De Villiers, David Pieter de Villiers and Johannes (Jannie) de Villiers Graaff. His eldest son, De Villiers Graaff, who became leader of the opposition in the South African Parliament, also had the eldest grandson, David de Villiers Graaff, the third baronet, baptised thus. The tradition has been continued since the eldest great-grandson was also named De Villiers Graaff.

Nort, who eventually worked as a blacksmith in Villiersdorp, was not a wealthy man. He became known as a tooth drawer. Teeth were drawn without sedation, but if help was brought along to hold the unfortunate patient down in a haystack while the “dentist” dealt with the matter at hand, a discount would apparently be given.9

The area’s remoteness, which had to make do without good roads and public transport, contributed to the meagre existence of most people. Poor in material terms, many, however, had a wealth of children, recounted Cobus le Roux, in his 80s.10 Due to a shortage of labour, many children had to start working at a very young age, like Le Roux’s ancestors. His father, Awie le Roux, grew up a poor farm boy, also the child of a bywoner like the Graaff brothers on Wolfkloof. “Together with the Graaffies their day’s work consisted of herding cattle and pigs. Every day’s work was undertaken with a cape made of a grain bag as protection against the rain and cold, and wholemeal bread with moskonfyt (grape syrup) to eat.”11 Cobus le Roux’s father told him that Dawie Graaff, as he was called then, used a large black pig as his mount.

Limited education was offered by travelling schoolmasters. Little Dawie Graaff initially went to school in Villiersdorp in an old coach house set up as a school for younger children. It was probably a church school that the Dutch-speakers founded in 1866 in opposition to the English school in town, and Dawie was one of around 15 pupils who were taught by a certain Mr. Hartley.12 Apparently he was bright, and old inhabitants of Villiersdorp believe he might have passed standard 3 (equivalent to grade five), or thereabouts.

Cobus le Roux emphasised that, although the children had limited educational opportunities in terms of schooling, they received a thorough education at home: “The atmosphere in the parental homes was truly Christian, and life-shaping Bible texts graced the walls. Family worship was a regular affair. Strict admonitions and punishment were the order of the day. Immoral behaviour was not tolerated. Respect for older people and subjection to authority were generally applicable rules. The people stood together and supported one another in times of need and tribulation and when an animal was butchered, people from the whole neighbourhood got a meat packet. Trustworthiness in word and deed, industriousness and honesty were generally applicable rules. Due to this approach to life, children were equipped from a young age to reach unheard-of highs in life, which also, and especially, was the case with the Graaff and Le Roux families.”13

The references to the Graaffs and Le Rouxs were later corroborated. Awie le Roux had to “spend [his] life almost illiterate… only being able to write his name, but at least he could also read fluently”, according to his son, Cobus. Notwithstanding, in 1934 he bought Bo-Radyn, where he had worked as bywoner, at an auction. When the auctioneer doubted Awie’s creditworthiness, approval had to be obtained from Standard Bank in Worcester. The bank replied to the effect that two such farms could be sold to him.14

And as far as the “Graaffies” were concerned, David Graaff would become known as a highly successful businessman and politician, a man of stature who would eventually become the great benefactor of Villiersdorp. In 1870 the erstwhile herdboy’s later fame was still waiting in the distant future.