Читать книгу Picturing Experience in the Early Printed Book - Elizabeth Ross - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 2

The Authority of the Artist-Author’s View

WHEN BREYDENBACH’S TOMB WAS opened eighty-five years after his death to help accommodate the tight squeeze of a nearby burial, his corpse was found “still wholly intact and unconsumed” with a lush growth of ruddy beard, all preserved by means of the “balsam, myrrh, cedar oil, and other fluids” he had brought home from his travels.1 The incorruptible body is a familiar hagiographical trope, where it signals the miraculous grace reserved for saints. Here it is applied to the creator of a famous book, who has achieved the physical sign of the saints’ dignity and eternal life through his reputation as an author and the special alchemy of his trip to the east. The Peregrinatio team built that reputation for him within the material confines of a printed book by working to stage the book’s reception. Some of the impetus for this lies in the publishing environment in the circle of the archbishop of Mainz, where print was an explicit subject of policy deliberation and action; Breydenbach takes up the terms of the Mainz debate in the front matter of the Peregrinatio quite overtly. In a diocese worried about the print industry’s decentralization and degradation of knowledge, the Peregrinatio provided a model for print through its process for assembling a diverse selection of new materials, made convincingly authoritative by their consolidation under a strong yoke of authorship. In text and image, the Peregrinatio is constructed to argue for eyewitness testimony as a guarantor of credibility, and Breydenbach pulls printed images into service to do this work of reimagining the author’s material presence in a book.

The Censorship Edict of 1485

The first book on which Breydenbach is documented to have worked, the 1480 Mainz Agenda, provides an example of one way bishops harnessed print technology to strengthen the reach and effectiveness of institutional leadership: they issued episcopally authorized editions of the liturgy. Falk Eisermann’s study of the press of Georg Reyser in the service of the Würzburg prince-bishop shows how the bishop’s arms were used at the front of a 1479 Würzburg missal as a license to advertise the authority of the critical edition, as part of the bishop’s public self-fashioning, and as part of a larger program to use print in the central administration of his diocese.2 Quality control was so crucial to that commission that readers were employed to check for errors in each printed copy, a measure that eliminates any labor-saving advantage to mechanical reproduction and suggests a certain suspicion that the technology was not foolproof.3 The Mainz Agenda presents a standardized version of diocesan practice, produced under the name of the archbishop (at that time Diether von Isenburg) and with his arms as a visual sign of his endorsement.

For the printer Peter Schöffer, whose press issued over 80 percent of Mainz publications in these years, similar commissions of missals and ordos represent a considerable aspect of his output. From 1476 to 1488, the ten years before the publication of the Peregrinatio through its last Mainz edition, his press published five broad categories of works, all in Latin except for the last: papal and ecclesiastical pronouncements, including indulgence materials (seventy-two editions); works for a clerical audience, such as confessors’ manuals or a commentary on the psalms (five); liturgical texts, in particular ordos and missals (eight); texts for academics and university students on law, logic, and Latin style (five); and works and announcements in Latin or German for a more general audience, such as almanacs, an invitation to a shooting match, and a vernacular cookbook (ten).4 This last category includes the Gart der Gesundheit, but not the three editions of the Peregrinatio. Miscellanea may edge out liturgical books for sheer numbers, but the five missals for the different dioceses represent the press’s most significant critical and typographical projects in these years. As a participant in the enterprise that first developed movable type, Schöffer carries a pioneering pedigree that belies the conservative content of his later production. This conservatism lies not simply in the number of works for a clerical audience, which still comprise the majority of readers of any kind, but in the number of editions issued by a central ecclesiastical authority or its agent, as a means of promoting homogeny in the religious services of his jurisdiction.

Beyond the strong episcopal presence in Mainz printing through commissions, the archbishop sought to shape press output by another means. Less than two weeks after his formal installation, Archbishop Berthold von Henneberg sharply criticized the publishing industry in an edict that provides rare documentation of an early institutional response to the technology through an attempt at censorship.5 The directive requires that books on any subject translated into German be examined by scholars at the universities of Mainz or Erfurt or by similarly credentialed clerics in Frankfurt before they can be printed or sold. Ignoring the mandate risked excommunication, confiscation of the volumes, and a penalty of one hundred gold coins. Although Frankfurt did not have a press before the sixteenth century, the city’s semiannual fair was already a nexus of the international book trade, so that the archbishop’s decree represents an early attempt to manage print media at a key node in the network for the circulation of both books and industry monies. The edict also invokes the unique status of “our golden Mainz” as the origin of the new art with a rhetorical flourish that seems to reflect a real sense that Mainz authorities have a responsibility, if not a special prerogative, to defend the “honor” of the art of printing in order to keep it “most highly refined and completely free of faults.”6

The oldest documented copy of the edict, from March 22, 1485, was addressed to the priest in charge of pastoral care (pleban) for Frankfurt’s most important foundation, the Church of Saint Bartholomew. It was sent to the city council of Frankfurt with a summary letter in German, and it instructed them to choose one or two credentialed scholars, to pay them an annual stipend, and to let the pleban (himself a doctor of theology) and the other scholars evaluate the translated works for sale at the city’s fair. On May 1, the prince-bishop of Würzburg, one of the archbishop’s suffragans, had the mandate printed to be read also from the pulpit.7 The order was then reissued by Henneberg on January 4, 1486, in a version that named four scholars from the University of Mainz to serve as a review board there, with one expert from each of the four faculties of theology, law, medicine, and arts, and a letter to Henneberg’s suffragan bishops exhorted them to enforce the order with secular leaders. In the directive, the archbishop expresses particular horror at the translation of the text of the mass (Christi libros missarum officia) and other works that express “divine matters and the apex of our religion,” as well as the provisions of canon law, but the composition of the Mainz review committee and references to “works in the remaining fields” make clear that he was concerned with texts across a wide range of subjects.8

The archbishop introduces his edict by echoing his former mentor, Nicholas of Cusa, in extolling a “divine art of printing” for making human learning easily accessible. But men have misused the gift. In their greed for money and vainglory, “some foolish, rash, and ignorant people” seek to expand their sales, so they translate texts into the vernacular.9 Henneberg objects to this on several counts: language, reading context, and shoddy product.10 Over the long history of using Latin for sacred matters, the language and its users have developed terms that lend Latin a professional finesse that vernacular languages lack. Moreover, just as a body of qualified readers has reached consensus over conventions of Latin usage, so the meaning of texts is properly determined through the give-and-take of scholarly debate. It is not just that poor approximations of subtle texts are being put in the hands of the “common people” and “laymen, uneducated men, and the female sex.”11 These audiences cannot understand them because they do not participate in institutional—as opposed to private—reading practices, where extracts of raw Scripture are buffered by interpretation: “Let the text of the Gospels or Paul’s letters be seen [as an example]; no reasonable man can deny that you need to supplement and fill in from other texts.” And what of texts, he asks, whose meaning “hangs from the sharpest debate” among scholars in what is meant to be a “catholic” church?”12 The edict champions an ideal of expertise that arises from lifelong study of the most recondite writings. While he is at it, Henneberg also decries basic errors or deceits in works from other fields: the incorporation of raw falsehoods, the use of false titles, and translators’ attributing their own inventions (figmenta) to distinguished authors.

The archbishop is concerned in part about the fixity of sacred texts, which suffers through poor translation, but he is also concerned about stability of meaning, which arises not from the text itself but from its reading context. Henneberg approaches this as a social problem, rather than a problem with the medium per se, and according to his analysis, it is the structure of print commerce that undermines fixity and stability.13 He intervenes, therefore, to try and engineer these qualities. In creating review boards, he inserts a new readership between printer and consumer, effectively restructuring the flow of works so that they are intercepted and vetted by institutional representatives who stand in for the scholarly community that traditionally shaped a work’s reception. It is not just a question of fixing a text, but of maintaining the proper parameters for evaluating interpretations.

The archbishop seems also to see himself, the church’s anointed representative and the head of the clerical estate in the empire, as the guardian of sacred writings with the charge to control their dissemination. The concept of copyright per se did not yet exist, and the legal conception of licensing was still in its infancy. Henneberg acts, however, much like a copyright holder (to express his actions in forward-looking terms). He invents a justification for his right to control not just the Bible itself or liturgical books, but all texts written in the sacred language of Latin on subjects touching Christian doctrine or God’s creation. Then he establishes a mechanism to assert his privilege.14 This works in tandem with quality-control strategies adopted by dioceses in commissioning new editions of their liturgical books: these circulate like critical editions, proofed and distributed from the center, under the imprimatur of the bishop.15

Breydenbach’s Self-Presentation as an Author

The Latin text of the Peregrinatio was composed in the year of the edict, and the German version was published six months after the edict’s reiteration.16 Moreover, the Gart der Gesundheit, Breydenbach’s herbal, came to press six days after the edict, from Schöffer’s press, which had just been used to issue a different archiepiscopal order and would continue to be favored by the archdiocese.17 Considering Breydenbach’s particular standing as a holder of high clerical office who was thoughtfully active in the printing industry, scholars have considered that he himself may have suggested the edict, ghostwritten it, or otherwise molded its content.18 With fluid energy, he engages Henneberg’s arguments in the dedication to the Peregrinatio, casting his project to make a book as a project to take advantage of the benefits of printing while avoiding its hazards. The edict, issued by the archbishop, and the Peregrinatio, orchestrated by a member of his circle, should be considered in tandem—a stick to impede the circulation of problem books followed by a positive model of how books should be produced.

Woven throughout the dedication are the expected statements of the author’s inadequacy, especially in the face of the dedicatee’s extravagantly praised merit. Breydenbach is the widow of Mark 12:41–44 and Luke 21:1–4 who makes the greatest offering because she offers all she has to give, even if it is but a paltry contribution in absolute terms (2v, ll. 23–24). Even within that formula he achieves a moment of self-congratulation in acknowledging that the countergift of the dedication is incommensurate with the goodwill, great love, graciousness, and favor the archbishop has always shown him, as everybody knows (3r, ll. 31–39). Breydenbach goes beyond these common expressions of modesty, however, to invoke the editing and correcting work of Henneberg and his representatives:

If this work also be lightly valued at first glance and, consequently, does not come to be very much edited [gestraffet] or corrected, as nothing important hangs on it, still I do not want to let it come out without your princely grace’s knowledge and consideration of it beforehand, not only to demonstrate reverence to your princely grace …, but also because I want to add advantage to this little book and work…. If this work were seen to come, checked and examined, from your gracious princely hand, it would undoubtedly gain more credence, luster, and worth. Above all for the reason that … nothing ever came under the rasp and test of your princely grace (which is quite sharp and takes off all the rust) that did not emerge most excellently straight, cleansed, and clarified. (2v, l. 43, through 3r, l. 14)

He invites the archbishop’s scrutiny, setting himself up as a model of proper submission to central oversight, with measures of sycophancy and market savvy as well. He does not just humbly petition for his patron’s approval; he explicitly submits to his or other scholars’ corrections. This dedication appears first in the Latin edition (2v, ll. 15–25), where there is no issue with translation and where, therefore, it serves as a voluntary social performance that enacts the paradigm of the edict without being compelled by its terms.

At the head of this dedication text stands the initial with Henneberg’s arms, the visual suggestion that the book does indeed come examined and tested from His Grace’s hand (figure 4). Breydenbach’s verbal supplication beneath an image of the archbishop repeats the structure of the metalcut in the 1480 Agenda, where a disabled indigent makes a meager offering to an enthroned Saint Martin, a bishop and the dedicatee of Mainz Cathedral (figure 9). The arms of the archbishop are strung above the saint, and the arms of Breydenbach hang below him at the level of the beggar. The layering of Breydenbach and the see of Mainz over the beggar and patron saint encourages the image to be read as an adaptation of the typical dedication miniature in a manuscript, where the author, on bended knee, presents a copy of his book to his enthroned patron. Here Breydenbach in all humility, a supplicant aided by the charity of Saint Martin, offers up his work to a patron who blesses him in return ex cathedra.

Breydenbach asserts that the Peregrinatio is intended for the edict’s ideal audience of clerics and educated elites, particularly preachers.19 The geographical description of the Holy Land is meant to elucidate the Map of the Holy Land with View of Jerusalem, so that it may serve “all who read or preach the Holy Scripture, which I especially want to encourage with this” (57r, 30–32). They will absorb the Peregrinatio’s information and then do the real work orally, disseminating the book’s message and arousing enthusiasm for it through sermons or reading aloud. In other places the author hopes this oral appeal will publicize the threat of Islam: if reading this book or hearing it read convinces noble men to resist the Turkish menace, then this book will be useful, he writes (167r, ll. 19–21). In another section, the Peregrinatio incorporates the work of a scholar found to be too soft on Islam and, therefore, potentially misleading for the general public. To mitigate that, the table of contents in the German edition points out a passage that is to be read “because of the common folk and uneducated people” in order to clarify the Islam section, and that passage is set off in the text with its own subheading (5r, ll. 7–10; 100r–103r). In the Latin edition, the same passage finds no special mention or typographical distinction, a difference that suggests how the production team attempts to guide the audience of the translation and address the concerns of the edict (4r; 86r–88r).

In reality, the Peregrinatio seems to have spread out of the hands of the elites through vernacular translations and new editions. At least the first of these editions was implicitly authorized by Reuwich, if not Breydenbach, when he provided the new printer in Lyons with the blocks. (Selling or renting blocks to another publisher was a common practice that allowed the original printer to make some money off others’ editions, since the new publisher could pirate the work with impunity with or without the initial printer’s cooperation.) Though early provenance information is rare, we know of at least one German copy that was read under different circumstances by members of “the female sex.” The Dominican nuns in Offenhausen, about thirty miles west of Ulm, coveted their German edition enough to try and deter errant borrowers with an inscription: “The book belongs to the women of Gnadenzell. Anyone to whom they lend it should return it as required and right away.”20 These nuns may very well have received their copy from Felix Fabri himself, who wrote a history of their house to contrast conditions before and after its reform in 1480.21

Breydenbach’s decision to pitch his work to elite masculine readers and the steps he takes to elevate his address should not be taken for granted. Female audiences, particularly those confined to cloisters, clamored for their own experience of the Holy Land, and their spiritual advisors obliged with texts that adjust style and language to their target. Felix Fabri’s four works about his travels were each tailored to a different audience. The Latin account was meant for readers like himself, while the German Sionpilger, composed in the early 1490s at the request of some local women of his order, refashioned his material as a guide to spiritual pilgrimage for them. Fabri’s guide sets forth twenty rules to direct the pilgrims’ behavior and state of mind before scheduling a devotional program of 208 days of imagined travel to the Middle East and back. Where Breydenbach hopes his book will serve as a prelude to real pilgrimage, Fabri crafts his book as an explicit substitute for physical travel. For more popular audiences he produced a German version of his Latin account, much condensed, and an even shorter account in verse intended to facilitate memorization of the order of holy sites. Francesco Suriano was less chameleon, but his treatise, discussed in the next chapter, was another example of an account pitched for women in a “simple style” that reproduces the instructional interchange between a nun and the priest assigned as her spiritual director.22

Breydenbach is well aware that pilgrimage accounts belong to a popular genre with a mixed audience. His characterization of the Peregrinatio as “lightly valued” and unimportant has a literal meaning apart from conventions of humility. The author seeks to remind his judge that he is not presenting the type of book, a work of theology or sacred scripture, that requires vigilant scrutiny. At the same time, Breydenbach seeks to distinguish his account of the Holy Land from the others that have gone before it, and although his efforts go well beyond the rhetorical posturing of the dedication, they are reflected in his argument there. Echoing Henneberg’s edict again and borrowing from Jerome, who quotes Horace, Breydenbach launches an attack on substandard books:

I have come to the opinion that … there is no end of making new books. (If anything of these times can be called new. I mean such things as receive new clothes only on the outside or are painted over in a different color than before yet their substance remains unchanged …).… New findings are getting well out of control…. It has already come to the point that … anyone who can simply hold the stylus or follow the particular forms of writing, he can turn [things] and move [them] around, and he thinks he has made a new book. And this is not only happening in the liberal or natural arts, such as grammar, dialectic, rhetoric, music, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and general philosophy, but also, what is more, in the sacred divine scripture. As Saint Jerome attests: doctors handle medicine and smiths that to which they are entitled, so the same for every craft. So it is alone the art of writing, especially the holy [scripture], that everyone presumes to understand. The educated and uneducated write poems and make books—the chatty crone, the witless old man, the blathering sophist—indeed, all people presume to write, to mutilate writing [zu rysssen die geschrifft], and to say something different that they neither know nor understand.23

The “foolish, rash, and ignorant” translators targeted in the edict are here even more colorfully disparaged as ninnies in comparison to the untouchable, sainted paragon of biblical translation, Saint Jerome. By the end of this reproof, Breydenbach has subsumed the edict’s concern about shoddy translation and greedy, deceitful practices into a criticism of more general incompetence in the making of books, with the implication that by composing books members of the craftsman class overstep their appropriate social roles. This, too, complements the edicts’ implicit assertion that the prerogative for creating and disseminating knowledge belongs to the clerical estate. The great works and great rewards belong to men of superior intellect who dedicate themselves to sacred or human learning from youth to old age, Breydenbach writes—another sentiment that parallels the archbishop’s mandate (2v, ll. 18–21).

Breydenbach does not presume to be one of those scholars. He claims another basis for his expertise: his completion the previous year of a lengthy pilgrimage, “as is recognized and known” (2v, ll. 34–35). As Breydenbach continues in the dedication, he develops an argument that says in essence, I may not be presenting your princely grace with a worthy work of the high genre of theology, but I have taken unusual care in composing a useful book with a pious purpose on a subject that suits my abilities and social station. He then alludes to the novel extent and effect of his working process by describing his “little book” (bůchlyn) as having “a form and size perhaps not seen before and brought to print with writing and pictures together” (2v, ll. 38–40). While following the archbishop’s argument in many ways, Breydenbach has at the same time subtly shifted the definition of expertise. The foundation remains knowing and understanding a subject matter appropriate to your class, but in this case that knowledge is grounded in personal experience, rather than longtime scrutiny and debate. In denigrating books that only pretend to be “new,” he has added an implicit call for some kind of originality. First he sets up the inference that his book offers that in contrast to those that merely “turn and move” things, and then he makes it explicit—a form and size not seen before, combined text and image, based on his own experience.

Shortly after the dedication, in a section entitled “Explanation of Intent” or “Expression of the Opinion of the Creator [angeber] of this Work,” Breydenbach will add two more claims that distinguish his project, and, therefore, implicitly bolster his justification for publishing: the extent of his research and his careful editing. First, Breydenbach emphasizes that during the journey he “investigated and learned all the things necessary to know with special diligence,” “sparing no expense.” For this purpose, he thought it worthwhile to bring along a “clever and learned painter, Erhard Reuwich of Utrecht.”24 In attaching the account of Reuwich’s work to his own, Breydenbach promotes the painter’s contribution as the visual counterpart to his own research. The three times Reuwich is named are the first times an artist is identified in the text of a printed book he illustrated. Breydenbach doesn’t just claim to have taken a painter with him on pilgrimage for the purposes of researching a book; he actually did. Describing it in the text in these terms was equally exceptional.

In that same section, in the Latin edition, Breydenbach also mentions that he had a learned man add explanatory material in Latin and German to his own offering (ad votum meum) (7v, ll. 8–10). Via Felix Fabri we know the collaborator was Martin Rath, a Dominican and Master of Theology at the University of Mainz, a colleague of the faculty members that the archbishop appointed to the censorship edict’s review board in January 1486. According to Fabri, this outside expert organized the building blocks of the text and assured the quality of the language.25 Fabri also seems to credit Rath with composing the catalog of Holy Land heretics, but that section closely follows a text by their traveling companion Walther von Guglingen. In the German Peregrinatio, the verb straffen stands in for the more detailed sketch of the commission in the Latin (10r, l. 27). Meaning “to edit,” literally “to tauten,” the word is also used to express the correcting work of the archbishop and his most learned scholars in Breydenbach’s dedication (3r, l. 1). Although the text does not advertise the contribution of the editor as it does the work of the artist, the editing process had a significant impact on the shape of the work, and it seems an important aspect of Breydenbach’s strategy for setting his book apart as a piece of careful scholarship for a sophisticated readership.

The extent of Rath’s intervention has caused scholars to ask if he should be considered the book’s author.26 However, Breydenbach robustly claims the author function for himself.27 While keeping the editor anonymous, he refers to himself as the work’s “auctor principalis” in the Latin edition (116r, ll. 42–43) and “angeber” (10r, ll. 1–3; 137r, l. 30) in the German, takes clear credit for the book’s conception and research in the front matter, and incorporated a travel account couched in the first person. How Breydenbach builds his authority in the book with forethought and purpose becomes clear from assessing the disconnect between what he claims about the text and images and what modern scholarship has shown about their origins.

The theory of medieval authorship articulated by A. J. Minnis, in particular for the twelfth through fourteenth centuries, often serves as a starting point for examining how later medieval and early modern authors and their transmitters (e.g., Dante, Chaucer, or Caxton) altered, exploited, or lived within the traditional framework while creating elements of our modern notions of authorship.28 Via Bonaventure, Minnis describes a spectrum of writers, from scribes who copy, to compilers who gather works and copy, to commentators who compile while adding some of their own explanations, to authors, whose own analysis forms the basis of the work, corroborated by other sources compiled to support them. This is not a spectrum of originality, as all four types of writers are understood to be mediating the ultimate theological authority of God in the Latin language of the Vulgate. The author has the greatest authority, from his long-standing reputation and his texts’ reception as formative members of a delimited canon, but there is no special privileging of the type of writing at that end of the scale.29 It is this same understanding that undergirds the archbishop’s conception of the church as the (so to speak) copyright holder of sacred scripture and many other texts, as the church is the earthly guardian of the sacred truths from which all kinds of writing derive.

For “writers” of visual images, an analogous conception of draftsmen as mediators of nature comes to the fore in a court case in Speyer in 1533, where Johann Schott of Strasbourg sued a rival Frankfurt printer, Christian Egenolf, for plagiarizing his press’s Herbarium Vivae Icones, a landmark in the production of herbals, richly and intelligibly illustrated from life.30 It is amusing in our context to note that Egenolf used the new images he copied to update, not Schott’s text, but Breydenbach’s Gart der Gesundheit, and he uses this different textual model as one point in his defense. More slyly, Egenolf argues that both books reproduce nature, in the form of the plants themselves, so that Schott cannot claim a privilege or special invention. The court’s opinion has not survived, though Egenolf’s blocks reverted to Schott, suggesting that the court had begun by this time to recognize at least the printer’s monetary investment in commissioning the blocks, if not the intellectual investment in the images’ design. Yet Egenolf’s argument, however self-serving, witnesses a conception of printmaking similar to that of authoring based in transcribing an external truth, even if that conception was in the midst of change.

When Breydenbach (or his source) leans on the Bible or a recognized author like Virgil (160r, ll. 6–8), he often mentions it, but he brings together without attribution a very long list of other texts: the pilgrimage account of Hans Tucher of Nuremberg; information about the peoples of the Holy Land and laments over the Muslim occupation of the Holy Land from the manuscript of Walther von Guglingen; a geographical description of the Holy Land attributed to Burchard of Mount Sion, a crusader-era monk; reports by the patriarch of Constantinople, the head of the Hospitallers, and other anonymous authors of Ottoman attacks in the Mediterranean; and many others.31 The origin of much of the source material of the book does speak for Breydenbach as the primary researcher, as so much came from Venice or his traveling companions. For example, beyond the borrowings from Walther von Guglingen, it seems plausible that Fabri, who carried Hans Tucher with him on at least one of his journeys, brought that account to his friend’s attention.32

There would be no contradiction for Breydenbach in the fact that most of the text of the Peregrinatio, including the first-person narrative of the travelogue, is drawn from other sources with interpolations as well as editing to streamline and customize the prose. Outside sources are compiled to support his contribution, which rests not necessarily in his analysis, but more fundamentally, in his eyewitness testimony that gives the collection its unifying purpose and imprimatur: “I, the person named as author, saw [what these other sources confirm].” Rather than mediating the theological authority of the Word through writing, he and his artist, or rather, their viewing, mediates the worldly Christian and natural order through images (as well as text). The censorship edict speaks of knowledge as a consensus that arises through discussion among learned persons, and this had traditionally taken the written form of a text scaffolded with other texts, as with the Pauline Epistles that Henneberg used as his example. In the Peregrinatio, it is Breydenbach and Reuwich’s first-person observations that are scaffolded by the compiled texts and by the images. The use of outside source material implicitly validates what the Peregrinatio team claims to have seen.

The origins of this support structure are obscured, however, by the act of ventriloquism that subsumes them under the first-person narrative and authorial claims of the text and images. In perhaps the most telling maneuver, Breydenbach emblazons his arms and the arms of the two other noblemen in his party at the center of the Peregrinatio’s attention-grabbing frontispiece. In honoring these three, the Peregrinatio frontispiece draws upon the common practice of Holy Land pilgrims’ commemorating their journey with public monuments, which ran the gamut from entire churches to chapel furnishings (like those provided by William Wey to the Chapel of the Holy Sepulcher at his monastery in Edington) to single images (like the stone relief of the Virgin and Child given by Breydenbach and Bicken to the Mainz Church of Our Lady) (figure 5).33 They gave the relief in thanksgiving for their safe return, and many pilgrims’ donations were similarly motivated. Pilgrims also put objects commemorating their accomplishment on display in other contexts where they did not serve a cult function. This was the case, for example, with the painting of Jerusalem that Breydenbach hung in his chapter house. Successful completion of a Holy Land pilgrimage also conferred social honors. After being dubbed Knights of the Holy Sepulcher during the all-night vigil at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, many then adopted the Jerusalem Cross as a heraldic device on portraits and other works marked with their arms.

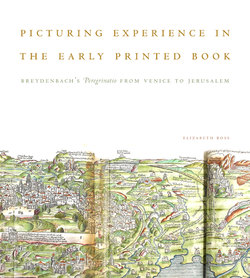

The use of a printed image as a vehicle for commemorating a pilgrimage was, however, a new form invented for the Peregrinatio. In the first decades of printing, publishers experimented with empty first pages; title pages with just type; title pages with type and ornament, a woodcut illustration, or a printer’s mark; or pictorial pages without any title information. While a title page grew increasingly common from 1480, the form of the paratext at the very front of the book had not yet stabilized as a pictorial hook to draw readers or as a label to identify books that had just begun to circulate far from their origin. Opening a book with a full-page woodcut across from the first page of text was and remained a highly unusual choice.34

Here on the inside, it turns the direction of its address, figuratively as well as literally, from an appeal to the reader to a commentary on the text. The adaptation of the Peregrinatio frontispiece in the Liber chronicarum will turn the focus back to the reader by replacing the lady and her heraldry with God the Father and two wild men, who display empty escutcheons ready to receive the arms of the volume’s owner (figure 10).35 (The Peregrinatio’s views are equally influential for the Nuremberg Chronicle’s famous profusion of city skylines.36) The example illustrated here happens to have belonged to the author, Hartmann Schedel, who has illuminated it with his own markings. The frontispiece of the other book orchestrated by Breydenbach, the Gart der Gesundheit, offers the same fill-in-the-blank bookplate, suspended from a foliage canopy that is in many other ways a prototype for the Peregrinatio’s opening image (figure 11). These swaps that displace the insignia of book’s readers (Gart) for its modern creators (Peregrinatio) and then back again to that of its readers (Liber chronicarum) begin to suggest the very distinctive choices of the Peregrinatio opening.

In featuring a convocation of eminent classical, Muslim, and Christian physicians who contributed to the knowledge collected in the book, the frontispiece of the Gart der Gesundheit is more typical of incunabula that adapt the conventions of medieval manuscripts. One type of manuscript frontispiece depicted an author on bended knee offering his work to a patron, as implied allegorically in the metalcut of the Mainz Agenda. That genre aside, medieval author portraits by and large depicted well-established authors of sacred texts. The fifteenth century did see a rise in secular and vernacular author portraits, as seen in the Gart, but the depicted writers, such as Aristotle, Aesop, or Chaucer, generally had long-standing literary reputations. Or a frontispiece can play to the new market for printed books with an image directly illustrating the content of the work. Peter Drach’s 1505 edition moves Reuwich’s image of the entrance court of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher from the interior of the book, where it originally introduced the description of the church, to the title page, where it advertises front and center what Drach wanted to market as the substance of the work (figures 12, 13). Reuwich has brought unusual technical care and prowess to bear on constructing an image that substitutes the visual rhetoric of nobility and the social sheen of the Jerusalem pilgrim for more traditional renderings of canonical authors or the book’s subject matter. And he chooses to place this unconventional, but forceful, framing of the foundation of the authority of the book where no image was necessarily even expected.

The Artist as Eyewitness

Just as Breydenbach asserts himself as author in the text, so the images strengthen his voice by adding the eyes of the artist. On July 14, 1483, Reuwich stood on the Mount of Olives, faced Jerusalem, and took in the view as an artist, a pilgrim, and a publisher in the nascent printing industry. We know he stood there as an artist because he translated his experience into the woodcut View of Jerusalem embedded into the Map of the Holy Land (gatefold). We can even call this image a perspective view because the print uses rough strokes of linear perspective in arranging the city’s most prominent monuments and because the disposition of urban topography aligns with the view from a single, identifiable vantage. From written testimony of pilgrims traveling with him, we can corroborate his presence at that vantage and pinpoint the date when the tour group looked down at the city to collect indulgences. And we know he considered the view as an innovating publisher because the book issued under his name tells us that the trip was in part intended as a research and reconnaissance mission to gather fresh and reliable material. We come to believe all these things first and foremost, however, because the view of Jerusalem and the other illustrations in the book have been designed to convince us that they are true.

To persuade, the Peregrinatio uses first a new kind of visual rhetoric—the emerging genre of the ‘view’—that here takes on special functions when inflected by the text and conjoined to another nascent media format, the printed book. More specifically, while the wider genre of the view looks out on any expansive landscape or vista, the Peregrinatio’s views of Venice, Modon, Candia, Rhodes, Parenzo, Corfu, and Jerusalem belong also to the subgenre that pictures cities and towns. While they are not the first examples of the city view in the west or even in the north, they are among the very first, made at a time before the city view or the city plan had coalesced as a genre, with shared purposes, conventions, and meanings. The type of city view showing a panorama that transcribes observed urban topography seems to have crystallized in the 1480s with the almost simultaneous creation of several views of Italian cities. A forerunner from circa 1466–86 is the painted Tavola Strozzi, which depicts a panorama of the return to Naples in 1465 of the victorious Aragonese fleet after the Battle of Ischia (figure 14). A woodcut view of Florence with a chain around its edge remembers a lost engraving by Francesco Rosselli, dated to the artist’s stay in the city between 1482 and 1490 (figure 15). From 1484 to 1487, Pinturicchio frescoed the Villa Belvedere at the Vatican with a series of views of Florence, Genoa, Milan, Naples, Rome, and Venice, now largely destroyed. Correspondence and other written testimony attest the loss of further examples, most importantly one view of Venice (Venetia in disegno) reported to have been created by Gentile Bellini for Mehmed II and another (retracto) drafted by his father, Jacopo Bellini, and retouched by Gentile in 1493 for Francesco II Gonzaga.37

Although the Peregrinatio’s illustrations belong to this development chronologically, their eccentric context opens their meaning beyond what is typical for this particular category. Juergen Schulz developed the term “emblem” to describe how the medieval progenitors of city views symbolized moral values rather than communicating topographical information or conveying a portrait likeness. Maps and seals represented cities as a compact grouping of structures, usually conventional but occasionally with recognizable components. Schulz’s term “emblem” serves as both a functional and formal description.38 Even with the introduction of a new style that presented cityscapes with atmospheric or linear perspective as if seen from a fixed, open vantage, city views were still regularly instrumentalized for political purposes, if not also for moral or religious ones.

The political content of maritime triumphal entries could not be clearer, though the Tavola Strozzi, likely displayed in the home of Filippo Strozzi, would also have advertised his personal triumph in helping finance the 1464 flotilla while making his fortune in exile in Naples.39 In addition to a view of Otranto (where Mehmed II’s forces were repelled from Italy in 1481), Filippo’s inventories record three views of Naples, none of which definitively match the Tavola Strozzi, and he commissioned a fourth as part of a lettucio, sent as a gift to King Ferrante.40 David Friedman has argued that the View of Florence with a Chain encodes rhetoric in praise of the city. The exaggerated prominence of the Duomo at the center of the image, for example, evokes Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem and the Florentines’ conception of their city as a New Jerusalem with the cathedral at its heart. Reuwich’s treatment of the Temple as the Dome of the Rock may have influenced Rosselli.41 Pope Innocent VII’s motivations for commissioning the Belvedere cycle remain murky. He may have wanted to revive a classical form of villa decoration as well as make a political statement about his authority to marshal the forces of rival Italian city-states.42 If the Belvedere cycle did have political meaning, then it would join the other three Italian images in breaking from the emblem format, while still remaining tied to its basic conception as a work of civic or personal and familial promotion.43

Reuwich certainly used his images to convey political messages, as we will see in chapters 3 and 5 for the View of Venice, View of Rhodes, and View of Jerusalem. Since the beginning of its development, however, the overarching genre of the ‘view’ has also carried an authorial voice within it that the Peregrinatio brings strongly to the fore. Picturing or writing about the view from a mountain or other commanding vantage has a long history, as an expression of the subject’s experience of vision and of man’s relationship to the built and natural environment.44 While people of all eras have climbed mountains and gazed out at the vista, in the Middle Ages they did not publicly relish that kind of view as an important category of experience or as an appropriate subject for literary or visual representation. In our era, the view from above, photographed from a skyscraper or by a satellite, can recapitulate the power of technology and rationalized systems, like modern cartography, to provide an overarching, abstract, and seemingly neutral representation of space. For the Romantics, the view could offer a privileged moment of revelation by bringing the subject in contact with the sublime. Beyond different periods’ particular articulations of the genre and the issues it evokes, the view plays a fundamental role in the overarching history of Western art since the Renaissance. One of the core histories of that tradition describes an ongoing exploration of the interplay between mimesis and the viewing subject, brought together in the format of the painting that posits a slice of the world constructed as a slice of the viewer’s field of vision.

The meanings of the word “view” reflect this conflation of an act of seeing—an instance of sight or an individual’s field of vision—with the object of sight—the prospect seen or depicted in a picture. These are then further entangled with the multiple uses of the word “perspective”: it describes both an individual’s view (with emphasis on how a particular vantage delimits the field of vision) and the artistic techniques by which such a view is represented, in particular atmospheric and linear perspective. And, of course, both words can refer literally to sight centered in the eye or metaphorically to mental or spiritual attitudes or cogitations. Within this rich semantic arena, the Peregrinatio’s woodcuts make most potent use of the intersection of “view” and “perspective,” of the way in which an image of a vista, a ‘view,’ can point back outside its frame to the artist’s or viewer’s implied standpoint, his “perspective” or point of view.

The mathematical system that is the technique of linear perspective relies on this link between the artist’s standpoint and the image, and the manipulation of linear perspective has provided a basic means for investigating and expressing the relationship of viewer and viewed. The development of the pictorial genre of the ‘view’ in the fifteenth century dovetails, then, with another of the century’s most vigorous artistic experiments, the development of linear perspective. Both are often analyzed in terms of their ability to deliver heightened mimesis, just as the achievement of the Peregrinatio’s images has been measured against their topographical accuracy. But the genre of the ‘view,’ the technique of linear perspective, and the Peregrinatio’s woodcuts also generate meaning in this other way, by exploring the dyad of viewer and viewed—or rather, the triad of the viewing artist, the viewing reader of the Peregrinatio, and their shared view of the people, places, and animals depicted. Embedded in a book, the Peregrinatio’s images speak also with an author’s voice to a reader across a text, and it is this overlay of author-artist, reader-viewer, and text-image that makes the woodcut views of the Peregrinatio such an unusual and potent contribution to the emerging genre.

The Peregrinatio’s city views are helped along by their coarse use of elements of linear perspective, exemplified by the rendering of the Dome of the Rock (Templum Salomonis) in two-point perspective on the center stage of the View of Jerusalem (gatefold, figures 16, 84). The precinct around the Dome of the Rock, a plateau largely enclosed by porticos, walls, and buildings, is known as the Temple Mount in Judaism, for its legacy as the former (and future) site of the two destroyed (and to-be-restored) Jewish Temples. In Islam, it is the Haram al-Sharif (Noble Sanctuary) that Muhammad visited during the first part of his miraculous Night Journey (Koran 17:1). Italian experiments with perspective often worked with just such an octagonal shape isolated in a piazza; for example, the Second Temple inspired by the Dome of the Rock in Perugino’s circa 1480–82 Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (figure 17) or Brunelleschi’s rendering of the Florence Baptistery, one of linear perspective’s most foundational moments. The orthogonals from the roof of the Al-Aqsa Mosque can be integrated into the Dome’s perspective scheme; they intersect those from the left of the Dome of the Rock at a rough vanishing point midway between the two buildings.

That is the extent of any diagrammable precision. The orthogonals of the roofs of the structures around the Christian Via Dolorosa loosely come together in a zone above the Dome, where they meet their counterparts from the other side of the city. There are pockets of apparent disorientation, for example at the far right corner of the Haram, where the rendering compromises the clean lines of the complex. There is also a tipping forward of the front of the city that can be taken as a tactic to elevate Golgotha, which lies toward the rear. Of course, the streets and buildings in situ, including the elements of the Haram itself, are not laid out in a clean rectilinear pattern, so that perfect convergence would have required the artist to willfully remap the city according to an ideal plan. The heterogeneity of the pictorial space does not betoken flaws in the execution of an ideal. As discussed in chapter 5, for example, the minarets on the north (right) side of the Haram were recorded in detail independently and inserted into the composition, to be absorbed by formal techniques for proposing a unified view. With Reuwich, heterogeneity does not fracture perspective; rather, perspective and the rhetoric of the ‘view’ coheres the heterogeneity of artistically assembled elements that represent the historically and geologically complex space of the city.

The effectiveness of the View of Jerusalem as a work of perspective does not, however, rely on the geometric discipline of true linear perspective. Its persuasiveness arises from the image’s ad hoc construction from a distinct perspective, and the text’s verbal scaffolding of this visually rhetorical structure. For the View of Venice (figure 1), the island of San Giorgio across the canal from the Doge’s Palace provided the standpoint; for the View of Jerusalem, it was a vantage on the Mount of Olives (figure 18), as explored in chapter 5. The images’ power comes not from intellectually principled and rigorously consistent geometry, but from the binding of panoramic views both to the material circumstances of a book and to a narrative context that insists on the images’ origin in an act of viewing.

Reuwich’s views are the first explicitly connected to an artist’s act of on-site looking, and the text is emphatic in establishing this relationship. Breydenbach does not just name Reuwich three times; he expounds his purpose in detail. The painter was brought along to portray the well-known cities skillfully (artificiose effigiaret) to the extent that it is possible to do so accurately (quoad magis proprie fieri poset) (7v, l. 7). In the German, the formulation that describes this drawing connotes a true relationship to the original (ab entwürffe, eygentlichen ab malet) (10r, ll. 23–24). The beginning of the Latin encomium to Venice repeats this in another form, advertising that the city “is portrayed here according to what was seen” or that the city, “[shown] here was afterward portrayed as it looks” (civitas veneciarum … hic sub aspectum consequenter effigietur) (10v, ll. 40–41). The first is preferable to match the present tense of the verb, but the German translator seems to have found ambiguity. He uses the same phrasing as earlier, but interjects an odd parenthetical gloss on the Latin consequenter: “the mighty city and dominion of Venice follows after this, accurately drafted by the learned hand of the painter (afterward and maybe on par with)” (eygentlichen [nach dem v eß mag syn vff eben] ab etworffen mitt gelerter handt des malers) (14r, ll. 28–30). The absence of an image is also used to bolster the artist’s credibility by seeming to demonstrate his willingness to withhold a picture rather than substitute someone else’s experience or imagination. Even though pilgrimage galleys generally stop at the “rich and mighty” city of Ragusa, a strong wind kept their boat from nearing that port. Consequently, there is no view of Ragusa in the Peregrinatio because the city “was not visible enough to us that it could be accurately drawn by the painter.”45

These passages also acknowledge the role of collecting and collating material, especially in the map, and together the praise of that work and the particular emphasis on the Holy Land sites support what the themes and organization of the volume also convey: the Map of the Holy Land with View of Jerusalem was the intended heart of the artistic program, even though the View of Venice filled more woodblocks. The Latin edition specifies that Reuwich depicted “the arrangements, positions, and forms of the succession of more powerful cities that make up the route of the passage by land and sea from the port of Venice and especially of the sacred sites in the Holy Land” (7v, ll. 4–7). The artist did not just portray these elements; he also “transferred them to his map, a work beautiful and pleasing to see” (7v, ll. 7–8). In German his subject is “the notable places on water and land … and especially the holy places around Jerusalem” (fol. 10r, 23–24).

These Animals Are Truly Depicted as We Saw Them

This verbal and visual strategy is not limited to the city views. The caption on Reuwich’s collection of animals reminds the reader that they, too, are supposed to be “truly depicted” as the pilgrims “saw them in the Holy Land” (figure 19).46 Seven examples of Holy Land fauna are brought together within a single frame above those words, which the presence of a unicorn (Unicornus) seems swiftly to belie. For today’s viewer this mythical beast is perhaps the first, most conspicuous sign that we might have reason to doubt the images’ claim to be based on an artist’s on-site transcription of what he saw, though we would be wrong to read its inclusion as a deliberate lie. Frederike Timm has pointed out that Reuwich’s views of Venice (figure 1), Parenzo, and Modon (figure 35) omit conspicuous fortifications and other structures erected before his arrival, while otherwise depicting the cityscape with unusual accuracy. The absence of the more recent structures suggests that woodcuts are based on acquired images drawn decades earlier. For Parenzo, a shift in the viewing angle suggests that Reuwich combined two views in order to create a more complete report.47 The ploy of explicitly excluding Ragusa is all the more notable, as the pilgrims do include views of Candia, which they saw from sea but where they do not seem to have landed, and Corfu, where they stayed for only a short while at anchor on the outbound journey and for a short winter’s overnight on the return trip.48 At issue here is not the original authorship of the drawings that underlie Peregrinatio woodcuts, but the intellectual and material labor of convincingly transforming heterogeneous materials into a unified body of work.

Elsewhere in the Peregrinatio, the author’s declarations in the text implicitly caption the views with the statement “The artist saw this,” but with the animals, the claim and the proposed object of sight come together on one sheet. This single page succinctly diagrams how the rhetoric of the eyewitness is constructed—and then used to credential and cohere a work that is in fact composed of elements drawn from representationally and epistemologically diverse sources. For this menagerie, the verbal statement’s visual corollary is not the structure of the perspective view, but the pictorial format used to illustrate categories of flora and fauna in books of natural history, as in illustrated printed editions of Conrad’s Buch der Natur (Book of nature) (figure 20).49 Each chapter of Megenberg’s book discusses one category (e.g., animals, birds, sea wonders, fish, bugs), and each begins with an illustration of members of the category loosely arrayed in a simple frame with minimal setting. The members of each group share certain characteristics of form and habitat (for example, wings and air for birds), and the illustration shows off the diversity of forms within the group while visualizing the textual catalogue that constitutes the text. Reuwich has borrowed a framing device that normalizes his collection as a category of natural philosophy. This repeats more succinctly how the peoples of the Holy Land are cordoned off in a documentary register, where they cater to curiosity with their own menagerie of costumes, but within a visually and textually disciplined framework, as explored in the next chapter.

The treatment of individual animals encapsulates different types of experiences of the exotic, and the presentation of the group as a whole exemplifies how, as a book, the Peregrinatio framed and disciplined the expression of those experiences. At first glance, the “Indian goats” (capre de India) seem curious only for being utterly pedestrian amidst a collection of real rarities. But they belong where they are across from their partner, the unicorn, as marvels that work their wonder only in tandem with the viewer’s expectations. Each of the Indian goats carries a single attribute that marks its difference from the homegrown variety: pendulous ears. In this period, well before the introduction of Eastern breeds, European goats sported only short, pointy ears. Pilgrimage accounts testify to the fascination of these types of differences, namely long ears and tails, in the most quotidian of animals, goats and sheep.50 For the unicorn, the artist and his party had a name and a mental image before they had the opportunity to observe a real specimen. They brought with them an expectation waiting to be fulfilled, and it was. The knowledge the pilgrims (and the reader) bring with them about goats opens them up to a moment of surprise.

Reuwich had good reason to believe there were unicorns in the Holy Land; his Muslim guide pointed one out on September 20. The Peregrinatio relates that, while crossing the Sinai Peninsula to Saint Catherine’s Monastery, the pilgrims saw “a big animal, much bigger than a camel,” that their guide told them “was truly a unicorn” (139v, ll. 39–41). Felix Fabri specifies that they espied the animal standing at a distance on the top of a mountain. According to his account, the pilgrims thought it was a camel at first until their guide identified it as a rhinoceros or unicorn and pointed out the single horn growing from its head.51 The pilgrims might not have believed their guide, however, had tourists’ wonder and wishful thinking and their own cultural mythology not already predisposed them to find unicorns in the wilderness of the Holy Land.

At other moments, the pilgrims, or at least Fabri, did suspect their guides were having a little fun at their expense. The guides’ state of mind remains elusive, though of course Fabri thought he had figured it out. When he came to them on September 16 to ask the name of their campsite, as he did every evening on their way through in the desert, a guide paused and then announced, “Albaroch,” with apparent mirth and to the general hilarity of the listening camel drivers. Or so Fabri imagined. They pressed the monk to write that down, which he did, despite what he understood as their continued laughter.52 Fabri seems to have conveyed the information he gathered to Breydenbach, who gives many of the same campsites, including the place “named Abalharock in the Arabic tongue” (140r, l. 17). Ever tenacious, Fabri researched the meaning of the name when he returned home and claimed to have found the answer: al-Buraq (“lightning” in Arabic) is the winged mount that the archangel Gabriel let the prophet Muhammad ride from Mecca to Jerusalem for his Night Journey.53 Fabri self-consciously suspects he was the butt of a jest, but he may have in fact received a straight answer. The group does seem to have been camping in a tributary of the Wadi el-Bruk, which can be said to flow to (al) Bruk.54 Just a few days later, that same guide called the creature they saw in the distance a unicorn.

The giraffe represents a different outcome of the impulse to map experience with names. The animal carries an Arabic name (scraffa), one of the many transliterations brought back by pilgrims in this era to form the root of “giraffe” and its variants in European languages. The adoption of the foreign word marks a shift from camelopardus (literally, camel leopard), the Latin name used by the Christian Fathers to remember a largely forgotten beast. Here the Arabic name also helps mark out the path of the pilgrim’s wonder. Handlers brought a giraffe, a lion, and a baboon riding a bear to entertain the group in the courtyard of their lodging in Cairo.55 Reuwich or one of his companions must have asked, “What is that?” and recorded what they heard of the answer, “Zarafa.” In the act of transcription, the word slipped away from the Arabic toward what would become the German Giraffe. The visual form of the giraffe slipped, too, away from an actual giraffe toward the form the animal would take in the European imagination.

At the bottom of the frame, a humanoid form with an electric mane, a tail, and a walking stick faces a camel (Camelus) he holds on a tether. For this beast, the artist declares he does not know the name (Non constat de nomine). If the giraffe represents the foreign import or the lost object found under a new name, the ape-man stands as the object whose utter strangeness defies culture and its naming. The scale of the creature and the anthropomorphization bestowed by the props delay our recognition that he is simply a baboon, a “canine monkey” (simia canina), as Fabri calls the primate he saw with the giraffe, using an archaic descriptor carried forward in the name for one baboon species, Papio cynocephalus.56 A former owner of a Peregrinatio in Houghton Library (f Typ Inc 156) helps bring the portrait into focus by coloring red the distinctive fleshy rump. The artist encourages us to mistake the monkey underneath the two miscues of scale and situation, perhaps to evoke the dog-headed people, the cynocephali, who were one of the legendary monstrous races thought to inhabit the margins of the world. Perhaps we see instead a caricature of the camel drivers who the pilgrims had to follow blindly and with some unease through the desert. Maybe he is the artist’s last laugh at them. Or maybe he is just a play on the human characteristics that made monkeys a symbol in this era of man’s folly and baser instincts. Either way, the artist himself is responsible for playing up the comedic or uncanny qualities of the baboon, and his refusal to name may reflect his ignorance as much as his desire to heighten the viewer’s sense of wonder.

Each member of this zoo represents a moment of curiosity and that curiosity’s visual expression. And each of these is composed of varying measures of preconception and openness, cross-cultural communication and uncertainty, and facticity and interpretation. Even within a class as narrowly defined as “Holy Land animals,” these examples hint at the heterogeneity of the artist’s encounters. We must also count al-Buraq, precisely because Reuwich does not depict him. He is the creature who translates from the Islamic cultural imagination only as an artifact of a pilgrim’s self-consciousness in the face of his own vulnerability as an alien. The frame set around the group reduces them to a set of animals varied in physical form but alike as statements of fact; however, membership in Reuwich’s category is not simply defined by a shared habitat. With the visual conventions of the page and then the caption, the pilgrims’ complex perceptual experience of each animal is reduced to a straightforward truth statement, “we saw them,” that functions much like the classification “birds have wings.” Having been observed by the pilgrims becomes the property that delimits and naturalizes the set. This is how experience becomes information in the images of Peregrinatio and how the information in turn obscures the complexity and heterogeneity of the experience and its recording.

By such means, the Peregrinatio develops the authority of a duo, Breydenbach and Reuwich, who function as “artist-author” in a manner that strategically recharacterizes the nature of their actual contribution. He arises from the very structure of the natural history box or the city views, which frame a collection of elements representing heterogeneous sources or aspects of experience in a way that obscures their origins beneath the leveling testimony of the artist’s gaze. The historical Breydenbach uses the authority of this construction to resolve (or try to resolve) one of the challenges of his project: how to develop the new medium of print while remaining obedient to the established social structure of knowledge. Even if based at least in part on sources handwritten or drawn by others, the “investigating and learning,” in other words, the seeking out, identifying, purchasing or manually reproducing, and integrating of the necessary materials would indeed have required “special diligence” that “spared no expense” during the course of their travels. What most distinguishes Breydenbach from the rabble of other would-be publishers whom he disparages is that by his lights, he does “know … [and] understand” the subject matter of his book. The sheer abundance of images and their freshness are meant to advertise this, as are Breydenbach’s social credentials of hereditary nobility, knighthood earned through pilgrimage to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, ecclesiastical office, and submission to the archbishop’s judgment.

Foremost, Breydenbach knows because he saw; he has sifted the material of the book through the filter of his experience, so he professes, and used his experience (and his wealth) to gather the material of the book. This is the purpose of the repeated claims that the artist observed the sites and accurately depicted them. The assertion that the artist-author has seen everything represented to the reader then slides into the claim that everything is represented to the viewer as seen by the artist-author. The slip from one formulation to the other happens so smoothly that we initially overlook that it is the images—more precisely the formulation of images as the artist’s view—that conjure the sleight of hand. Casting their material in the first person of the view makes visible Breydenbach and Reuwich’s strong claim to the special knowledge of the eyewitness.

At the same time, the creators of the Peregrinatio are also working within a traditional epistemological system that locates the ultimate source of authority in the communal consensus of a body of educated interpreters. These are the institutions for reading and scholarship that the archbishop moves to protect through his edict. Breydenbach seeks to position himself as an author who assimilates to a collective authority at the same time he adds to it; he undertakes to speak in the first person in order to have the Peregrinatio better accepted as a third person statement. This is, to his mind, a fundamentally conservative endeavor, but it demands a balancing act between “I saw” and “it is,” between the voice of an author and outside authority, and between the individual’s perspective and the communal overview. These are the demands that shape the assembly of the Peregrinatio and the crafting of its images.

Gart der Gesundheit (Garden of Health)

This understanding of the symbiosis of text and image can aid in interpreting Breydenbach’s other major book project, the 1485 Gart der Gesundheit, whose modus operandi provides a dry run for the Peregrinatio. The name “herbal” that is applied to this type of work—a compendium of therapeutic plants with some minerals and animals—understates the genre’s importance as a mainstay of period medical knowledge. While Schöffer’s 1484 Latin Herbarius, the same kind of book, contained 151 woodcuts, the Gart incorporated 382 (including the printer’s mark). It introduced sixty plants, ten animals, and eight minerals that had not been depicted in earlier herbals, including Schöffer’s Herbarius or even the manuscripts that transmitted the classical and medieval tradition. While over 300 of the illustrations were copied from miniatures in such manuscripts, as many as 77 seem to have been drawn fresh for the Gart, an assessment based on their style, their clearly identifiable form that is similar or true to nature, as well as the absence of any known models for them (figure 21).57 The Gart was the first guide to medicinal plants in German and the first herbal in any language to supplement woodcuts copied from manuscripts with woodcuts based on drawings from life. It was also just as successful as and perhaps even more influential than the Peregrinatio, with at least twelve copycat editions before 1500 and over sixty before Linnaeus, for example the litigated version published by Christian Egenolf and discussed above.58

The text of the Gart was composed by Johann von Cube, who was named the city physician for Frankfurt in 1484. The core of the book is divided into 484 short chapters that each treat a different substance, and for each chapter Cube compiled information from standard works of medieval German medicine and pharmacological botany, in particular Älterer Deutscher Macer (older German Macer) and Conrad von Megenberg’s Buch der Natur.59 The Codex Berleburg, a miscellany of such works, has been identified as one direct source for the text and as many as 29 of the illustrations, though likely fewer.60 Such vernacular works filtered the writings of classical authorities at quite some distance, but it is these prestigious authors with a certain patina, such as Galen and Dioscorides, whom Cube names.61 Marginal notations and recipes for medicaments demonstrate that Breydenbach himself owned the Codex Berleburg at least in the years 1475–77, although the content of the annotations in multiple hands suggests that during this time others contributed recipes to address Breydenbach’s various ailments (hair loss, weakening eyesight, loss of virility, and other problems related to aging as well as dermatitis, chest congestion, etc.).62

Nowhere does the Gart name Breydenbach, and beyond the Codex Berleburg, the evidence for his role in the project comes from a familiar-sounding passage in the foreword. There the unnamed author brandishes Breydenbach’s signature rhetorical credential: dissatisfied with the available visual material, he undertook a pilgrimage that gave him the opportunity to learn in the company of an artist, who depicted the plants accurately.

I had such a laudable work [the Gart] begun by a master learned in medicine, who according to my desire brought together in a book the potency and nature of many useful plants out of the [works of the] esteemed masters of medicine Galen, Avicenna, Serapion, Dioscorides, Pandectarius [Matthaeus Silvaticus], Platearius, and others. As I was in the middle of drafting and portraying the plants, I noted that many noble plants are those that do not grow in these German lands. I did not want to render those [just] on hearsay due to that, different from their correct color and form. Therefore, I left the work I had begun incomplete and hanging until I finished getting ready to travel to the Holy Grave, also to Mount Sinai where the body of the beloved virgin Saint Catherine rests in repose, in order to earn grace and indulgences. However, that such a noble work, begun and incomplete, should not remain behind [and] also so that my journey would not only save my soul, rather the whole world would want to come to [the] city [i.e., Jerusalem], I took with me a painter of reason with a deft and subtle hand…. I myself learned there with diligence about the useful plants and had them portrayed and drafted in their correct color and form.63

The frontispiece pointedly underscores these claims with its collection of scholars, presumed to represent Cube’s bringing together of said esteemed medical masters, and in the background a date palm evokes the Holy Land (figure 11). Were the painter of the pilgrimage not mentioned in the foreword, the compositional similarities between this frontispiece and other Peregrinatio woodcuts, in particular the framing arbor and the multicultural assortment of costumes, would still be enough to announce Reuwich’s participation (likely together with other artists). In the Peregrinatio, the figuration of Breydenbach’s credentials replaces the many contributors shown here, a reformulation that marks the shift in overall strategy toward bolstering Breydenbach’s single authorial voice.

Scholarly consideration of this passage has focused on trying to reconcile or highlight the discrepancies in the foreword’s account with the facts of the book. Johann von Cube’s generous referencing of antique authors can probably be explained by the period understanding of lines of transmission; they did not distinguish categorically between original and reworking as we do. More saliently, the fresh illustrations from life (or in some cases perhaps from unknown, unusually high-quality models) by and large represent plants either native to middle Germany or nonnative cultivars available there, as, for example, the indigenously more southern lavender depicted here. Several excuses have been proposed for this, but these literal preoccupations minimize the real achievement.64 As in the Peregrinatio, the emphasis is on the importance of Breydenbach’s own research, and the artist’s work is tied to his. Certainly, the passage implies that Reuwich was brought along to make images of exotic flora, but it does not state that outright. Breydenbach is a bit cagey here, on the one hand flourishing the prestige of pilgrimage, but on the other hand subtly hedging his claims about the result. The text reiterates the stated aim of the Peregrinatio, that the painter was brought along to create images that would entice others to pilgrimage. And while the Peregrinatio says that for the city views Reuwich “drafted from” or “drew from” (ab entwürffe, eygentlichen ab malet, eygentlichen … ab etworffen), in the sense of drawn “from” life, the Gart omits that preposition. This may seem a subtle point, but it gets to the pith of the claims of the Peregrinatio. Now that the writer, and by implication the painter, have seen the plants, they can be portrayed accurately. He is vouching for their correctness based on his personal experience and conscientious research, enabled though travel.

The Artist-Author’s View in Petrarch and Van Eyck

To watch Breydenbach position his works is to observe how an early printed book labored to establish its credibility and cohesiveness and how printed images benefited from this labor. The author bolsters his authority with the credibility of the images as authentic views; at the same time, the images gain credibility as authentic views from their association with an authoritative book, a book made authoritative through the author’s conception and presentation of the Peregrinatio project. “View” here is used in its broadest sense as an instance of physical sight, as the more general input of experience, or as learned opinion. “Authentic” means the image avers to conform to the experience of the artist, who has recorded the sight himself or verified the representation against what he himself saw.