Читать книгу Picturing Experience in the Early Printed Book - Elizabeth Ross - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

Introduction

THE PILGRIMS AND THEIR PROJECT

Gatefold

IN 1483, AN AMBITIOUS GERMAN CLERIC named Bernhard von Breydenbach set out to use the new medium of his day—print—to reconceptualize the form and making of a book. Our own historical situation has opened a special sympathy with those who experimented with printing in its first decades. We weigh the purchase of e-readers, navigate Wikipedia’s bounty of fickle facts, contend with piracy, and debate attempts by Google Books and others to shape jurisprudence. In all these ways and others, we apprehend a future transformed, without being able to anticipate clearly how its material forms, economic models, legal systems, or structures of knowledge will work out. Breydenbach did not feel the portent of his moment in quite the same way, but he stood, nonetheless, at a juncture in the history of media similar to the one we have been experiencing with the introduction of digital technologies. New technology presented new possibilities, but as creators and entrepreneurs innovated, they opened an era when the nature of a work of art—as well as the nature of a book, an artist, and an author—stood in flux.

Of this instability Breydenbach was certainly aware; he wrote a bit about it. His project offers perhaps the best window available onto the medial shift as a multimedia phenomenon, where the rethinking of the form and role of images is integral to the content, material apparatus, and cultural positioning of the work. He published one of the seminal books of early printing, known as Peregrinatio in terram sanctam (Journey to the Holy Land), the first illustrated travelogue, a work especially renowned for the originality, experimental format, and unusually skillful execution of its woodcuts. To accomplish that, he recruited a painter, Erhard Reuwich of Utrecht, to travel with him on pilgrimage to the Holy Land to research these images, create the woodcuts, and print the book. Taking an artist on such a reconnaissance mission was unprecedented, and with this travel their project engages another topic of particular concern—Christian European encounters with the Muslim Middle East. The pair grapple throughout the book with the challenge of Islam militarily, in the Ottoman Empire’s successful offensives, and spiritually, in the Mamluk Empire’s domination of Jerusalem and its built environment. Together author and artist presume to offer readers an authentic introduction to a Mediterranean basin caught in a contest between faith and heresy. But to do this convincingly, they must also work out their own model of authorship and art-making as they work through the problems and potentials of print.

Inspiring and facilitating pilgrimage was a stated and real aim of the book (2v, ll. 42–43; 7r, ll. 12–16; 10r, ll. 17–20). A good portion of the Peregrinatio is given over to describing the course of a Holy Land pilgrimage, providing readers with geographical information, and offering practical advice, such as a table of distances between Mediterranean islands, guidelines for their contract with the captain of a Venetian gallery or with their escorts through Egypt, and an Arabic-German glossary (165r–166v, 11r–12v, 136r–137r). The excursus on negotiating passage from Venice to Jerusalem and gathering supplies parallels the handwritten instructions Breydenbach provided to a local nobleman, Ludwig von Hanau-Lichtenberg, who went on pilgrimage in 1484 with his cousin Count Philipp of Hanau-Münzenberg.1 However, the Peregrinatio goes well beyond fostering pilgrimage. Its added intention is to raise readers’ concern about the centuries-old, but persistent ideological disappointment of European foreign policy and the contemporary manifestation of this disappointment—namely, Europe’s inability to dislodge the successive Muslim empires that had controlled the Holy Land since the fall of the last crusader outpost in 1291 and their fear of recent Ottoman incursions.

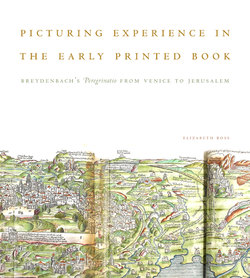

The woodcuts Reuwich produced include a complex and unusual frontispiece featuring a Venetian woman (figures 2, 45), seven city views of ports of call composed with rare topographical accuracy (one inserted in a resourcefully synthesized map of the Holy Land), renderings of the entrance court of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher (figure 12) and the aedicule over the grave of Christ (figure 89), six images of peoples of the Levant with seven charts of their alphabets (figures 7, 25, 30–32, 34), a page of Holy Land animals (figure 19), initials with the arms of the book’s dedicatee (figure 4), and his own printer’s mark (figure 3).2 Printed across multiple attached sheets, four of the city views and the map fold out from the book to a length of up to 1.62 meters for the longest View of Venice (gatefold, figures 1, 28, 35). Such technical achievement occurred also on the smallest scale, with the frontispiece in particular made possible by the precocious intricacy of the cutting of the print block to produce plastic modeling through cross-hatching that is unmatched by other contemporary woodcuts. Breydenbach and Reuwich published Latin, German, and Dutch editions of their work in 1486 and 1488 (about 180 of the Latin, 90 of the German, and 40 of the Dutch survive), and other printers translated it into French, Spanish, and Czech before 1500. The Peregrinatio pervaded the visual imagination of readers across Europe to inform paintings, prints, Passion parks, sculpture, maps, and other books. In total, there were thirteen editions before 1522, as the original woodcut blocks were passed from Mainz to Lyons to Speyer to Zaragoza, while also copied four times.3

Though some late fifteenth-century and many more sixteenth-century prints would mimic the scale and space of painting, Reuwich’s work stands out for the—at first—seemingly discordant yoking of the experience of viewing a panorama to the material circumstances of reading and the bound book.4 Artist and editor used these viewing experiences, including the visual rhetoric of perspective, as the foundation for creating a model of knowledge, authorship, and reading for print. Through pictorial, textual, and material means, the woodcuts are self-consciously constructed as eyewitness views that pronounce their origin in an artist’s on-site looking and recording. The first mode of viewing proposes a single viewpoint over a unified pictorial space, while the second mode offers the close-held, dispersed, sequential perusal of reading a map or an illustrated book—or of peering closely at the details of some painted panels.

The available information about the provenance of surviving copies, albeit dissatisfyingly meager, supports the supposition that the period readership adopted both approaches to the images. The Nuremberg patrician Hans Tucher’s own pilgrimage account was formative for the text of the Peregrinatio, and his hometown compatriot Hartmann Schedel’s Liber chronicarum (known as the Nuremberg Chronicle) would in turn look to the Peregrinatio for influence. Both these print authors owned copies of the first German edition that retained the full complement of illustrations.5 Yet a recent census of the forty-four copies of that edition extant in Germany shows that this is true for less than half of them. While some of the copies were no doubt unintentionally damaged or fleeced for their salable parts in later centuries, these results suggest, circumstantially, that some of the views were removed early to be used as independent images.6

The panoramic viewpoint of the views belies the book’s sympathies with the values and working methods of period cartography. At the heart of the Peregrinatio lies the Map of the Holy Land that surrounds the View of Jerusalem embedded within it, and the process for assembling this chart presents a microcosm for the construction of the book as a whole (gatefold). The Peregrinatio was created at the end of a century when late medieval mappae mundi were gradually giving way to charts that incorporated the modern findings of merchant-navigators into a systematic geographical framework like that described by Ptolemy. This cartography is not necessarily distinguished by the accuracy of its topography, but rather by an impulse to gather information from several types of sources and to integrate it, which means harmonizing geographical schemes that imagine and visualize space in disparate ways. Reuwich uses this critical procedure for collecting and collating knowledge in the construction of the Peregrinatio’s Map of the Holy Land. For the book as a whole, Breydenbach writes that he spared no expense or effort in gathering materials. This seems to be the case, as the text itself brings together the works of well over a dozen authors on various topics from pilgrimage to current events, and almost every image provides the spectacle of a place, person, or animal that readers would have never before seen.

Author and artist then wrap the product of this cartographic model—the map itself and the entire Peregrinatio—in the unifying cover of eyewitness authority, expressed as the artist’s view, depicted visually in his ‘views.’ The pictorial genre of the ‘view’ reached its greatest circulation in the eighteenth century, when such works for sale as a token of the Grand Tour came to be known as vedute (Italian for “views”). That term functions handily in art history to distinguish the genre and its products from other uses of the English version of the word. To call the Peregrinatio’s cityscapes vedute, however, would be to burden them proleptically with a history that was just emerging. They help invent a genre whose conventions and meaning were hardly resolved in the 1480s. For that reason, the cityscapes and their like will here be called simply ‘views.’ At times, single quotes will distinguish them from other types of views—such as the artist’s view (what Reuwich beheld on the trip), the author’s view (what Breydenbach opines in the book), or the reader’s view (what a period person experienced through the Peregrinatio’s pages). The choice to keep such a multivalent word is meant also to reconnect the pictorial work to its most fundamental rhetoric: the visual proposition that all ‘views’ arise from an act of viewing, namely, the artist’s view of the sites before him. Implicit within the Peregrinatio are also other types of views, even though we do not usually call them that—the cartographic view as expressed materially in the map; the view of space that the map engages in the reader; and the pilgrims’ cognitive map that structured their view on the road. By foregrounding so distinctively the pictorial form of the ‘view,’ the book catches up the reader in a connection between his own view and the artist’s.

The Peregrinatio project relies upon the pretense that everything has come together in the artist’s and author’s field of view, where it is endorsed as credible because they saw it. The book uses this visual testimony to cohere the elements of the book (mechanically reproduced text and image), to elide the seams among diverse sources, and to create an author. The instabilities brought about by print were the subject of explicit commentary and action in Breydenbach’s milieu. With his concern for giving the book a new form, filling it with novel sights, and building the cover of assertive authorship, Breydenbach gave an answer to that particular challenge.

After Breydenbach and Reuwich and the facts of their pilgrimage are introduced in this chapter, chapter 2 will look at how Breydenbach and his circle understood and responded to the print dilemma through the person of the author and his partner, the artist. The images of the Peregrinatio are constructed to say “I, the artist, saw” as a visual argument working in tandem with the text’s repeated declarations that they are, indeed, records of the artist’s act of viewing. These statements are amplified by their singularity; this is the first time the artist for a published book is identified or promoted in the text. Reuwich’s city ‘views’ are among the very first, and the use of the trope of the view here also amplifies themes developed by its earliest progenitors, such as Petrarch and Jan van Eyck. Later in the early modern era, the claim of printed images to be reliable copies of nature or other images will become routine.7 In the Peregrinatio, we see how this notion of authenticity was originally orchestrated.

Chapter 3 takes up the question of the Peregrinatio’s portrayal of the European encounter with Islam: how the theme of crusade pervaded the politics and financial strategies of church, empire, and press; how the Peregrinatio packaged the issues; and how its choices contrasted with the presentation of Islam in some of its source material. The Peregrinatio exemplifies the intersection of crusade rhetoric, indulgences, and print innovation that marked the culture of print in Mainz. The visual materials that show off what the team learned in Venice, some of their freshest materials and most forward-looking, serve this emphasis on crusade. The book’s text and images are not just organized to follow a pilgrimage, but to describe also a journey from a bastion of orthodoxy and resistance to Muslim aggression, Venice, to the Holy Land, a region overrun by heresy. The story of the Peregrinatio’s reception of the Levant is also the story of its relationship to Venice and vice versa. The Peregrinatio team and Venetian artists are mutually admiring and wide open to each other’s influence, but their different picturing of Islam demonstrates how its presentation can vary starkly with audience.

The View of Venice may be the Peregrinatio’s longest image, but the Map of the Holy Land with View of Jerusalem is its core construction, most essential to its message and most illustrative of the type of intellectual and artistic activity that animated the project. The creation of the map epitomizes the creation of the book. Chapter 4 parses the map to demonstrate this, while recouping its value in the context of period cartography.

Chapter 5 continues the focus on that woodcut, zooming in on the View of Jerusalem, which takes control of the center of the landscape. While Muslim patrons composed the built environment of Jerusalem itself to generate an Islamic experience of the space, Reuwich fights pictorially for a sovereign Christian view. He depicts a vantage near the place where pilgrims earned indulgences for viewing sites that Muslims forbid them to visit. This was a moment in the tour that served simultaneously to remind the pilgrims of Christian subjection and to overcome their subjection by means of a view. Reuwich offers a woodcut ‘view’ with the same double purpose of displaying both the center of Christian sacred history and an object lesson on the contemporary threat. He translates into a picture a practice shared then and now by all three Jerusalem religions, their setting up distinct, physical outlooks—contingent views dependent on vantage—that nevertheless show the city as they believe it to be absolutely. The artist’s personal experience of viewing the city endorses the ‘view’ he prints, which the reader then inhabits, encouraged by the routine of spiritual pilgrimage; and through the image of the artist-author’s authority, the contingency of the Christian point of view, physical and metaphorical, is fixed in place as a true image of Jerusalem.

Bernhard von Breydenbach and His Pilgrimage

The frontispiece introduces Breydenbach, or rather the lady on the pedestal does, with her extravagant dress amplifying the traditional conception of a shield holder—usually a fetching hostess or a playful creature such as a wild man, who presents a heraldic display (figures 2, 10).8 The person offering the shield lends the arms her good looks or his vitality, while providing an opportunity for exploring the female form or drolleries of costume and pose. On the last page of the Peregrinatio, a woman crowned with an exotic turban and sheer veil tenders a shield with Reuwich’s own printer’s mark (figure 3).9 On the frontispiece, she fulfills her role by gesturing to the shield, helm, crest, and title of Breydenbach, which are given pride of place on her right. Across her body, they face the achievement of Count Johann von Solms-Lich (Johannes Comes in Solms et dominus in Mintzenberg), an eighteen-year-old nobleman who also made the pilgrimage. He was escorted by a knight in the service of his family, Philipp von Bicken (Philippus de bicken miles), whose somewhat smaller and more wilted armorial bearings assume a lower position on the pedestal, commensurate with his station.10 Beyond Breydenbach’s noble birth, the frontispiece also invokes his church office, through the inscription below his shield that announces him as “Bernhard von Breydenbach, Dean and Chamberlain of the Church of Mainz” (Bernhardus de breidenbach decanns et Camerarius ecclesiae Moguntine), and through the pairing of this with the arms of his superior, the archbishop of Mainz, inserted across the opening in an initial that begins the text in the Latin, Dutch, and some of exemplars of the German editions (figure 4).

With the heraldry of the archbishop, the book’s dedicatee, Breydenbach pulls a fourth, more august personage into orbit. Breydenbach’s return from pilgrimage and his publishing activities coincided with the prime of his career, which was spent entirely in the service of the Mainz archdiocese. Born around 1435 to a family in the lower ranks of the nobility with a seat at Breidenbach, about eighty miles north of Mainz, Bernhard was educated from a young age at the school attached to the cathedral in Mainz, then from 1456 to 1458 at the University of Erfurt, which lay within the extensive territories subject to the archbishop.11 In 1450, Breydenbach was named a member of the cathedral chapter, a body of twenty-four clerics (each required to trace his noble descent through all sixteen of his great-grandparents), who elected the archbishop and assisted him in the running of the diocese. The archbishop was ex officio one of the seven prince-electors who met to choose each new Holy Roman emperor. Indeed, he was the chairman (Archcancellarius) of the prince-electors, with power and clout to represent to the pope, advise the emperor, and address affairs throughout the realm. Accordingly, the responsibilities and prestige of this cathedral chapter exceeded the norm, and the canons were generously supported by income from the chapter’s own significant territories and landholdings and from additional benefices and posts they filled. Breydenbach, for example, was appointed a canon at three local churches and a fourth about forty-five miles to the east in Aschaffenburg. There is evidence that already before his pilgrimage he also played a role in supervising the printing projects of the archdiocese on his superior’s behalf: his arms appear at the bottom of a metalcut on the colophon page of the 1480 Agenda Moguntinensis (Mainz Agenda). Issued under the name of the archbishop with his arms depicted at the top of the metalcut, this publication outlined the liturgical formulas for various rites as practiced in the diocese (figure 9).12

Breydenbach’s pilgrimage took place midcareer with at least three members of the traveling party brought together some time around February 1, 1483, when Breydenbach sent letters to Mainz requesting that his painter join him at the residence of Count Johann in Lich about fifty miles northeast of Mainz. Breydenbach seems to have called the painter in order to create a portrait of the young man, and documents confirm the artist answered the summons. A portrait made in 1528 by Hans Döring, presumably a copy of the lost original, professes to show the count at that age.13 Breydenbach is documented in Lich at least once more, returning to Mainz on April 13, and in that week he received permission twice over to absent himself from his duties, with one permit authorizing a six-month absence from a diocesan law court on account of plague and a second consenting to a year’s absence from the cathedral chapter for pilgrimage.14

On April 25, 1483, the traveling party formally set out from Oppenheim, a town about eleven miles south of Mainz on the Rhine, and reached Venice after fifteen days of travel. There they spent three weeks gathering provisions for the trip, touring relics and other sites, and contracting with the captain of one of the two galleys that transported pilgrims east that season. Holy Land pilgrimage was an organized affair, with galleys licensed by the state, and upon arrival at the eastern Mediterranean port of Jaffa (now Tel Aviv), pilgrims were handed off from the care of their captains to Franciscan monks, the Latin Church’s representatives in the region, who would take responsibility for shepherding them through their stay. The Peregrinatio group set sail on June 1, hopping among the ports of Parenzo (today Poreč, Croatia, June 3–4), Zara (Zadar, Croatia), Corfu (June 12), Modon (Methoni, Greece, June 15–16), Rhodes (June 18–22), and Cyprus (June 26–27), before arriving in Jaffa at the end of June just before the second galley of pilgrims, who had been cruising on a parallel course. There they were held in immigration detention until Mamluk officials arrived to process them, after which they were released to the Franciscans, who led them by donkey into Jerusalem on July 11 via a stopover in Rama.

A highlight of their time in the Holy City was the overnight lock-in at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher from July 12 to July 13, when the noblemen of the party were dubbed Knights of the Holy Sepulcher in a ceremony during the vigil.15 They also climbed the Mount of Olives; walked the Via Dolorosa, the path Jesus took from his imprisonment to his crucifixion; visited the Franciscans at their base on Mount Sion; and took excursions out of town to Bethlehem, Jericho, the River Jordan, and the Dead Sea. After ten days, most pilgrims began the trip back to Jaffa for the voyage home, but the Peregrinatio party and some others decided instead to make the arduous trek south to Saint Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mount Sinai. They waited in Jerusalem until August 24, in the meantime getting a chance to enter some sites that had been closed to the larger contingent, in particular the birthplace of the Virgin Mary, which had been converted to a (very prestigious) madrasa.

The expedition through the Egyptian desert to Mount Sinai took thirty days, and from Saint Catherine’s they took to the desert again for eleven more days, heading west to Cairo, one of the world’s largest cities, which they explored for twelve days against the background of Ramadan. They admired a troupe of exotic animals, a new mosque commissioned by the sultan, and the sultan himself holding court in the palace. Merchants in the market mistook them for a lot of slaves, offering to purchase them from their guides for ten ducats each (150r, ll. 30–35). On October 19 they embarked for a week-long passage downriver to Alexandria, where Count Johann succumbed to illness on October 31 and was buried with all the ceremony Breydenbach could muster in the Coptic Church of Saint Michael. The Peregrinatio mentions his death only briefly, but the description of Count Johann in the register of pilgrims making the trek to Saint Catherine’s monastery reads as eulogy: “Lord Johann of blessed memory, a Count of Solms and Lord of Münzenberg, in years the youngest and least, but in nobility and mind like no other, indeed, the foremost.”16 They were finally able to take ship for Venice on November 15, but, delayed by rough weather, they did not make it into port until January 8. The two noble survivors, Breydenbach and Bicken, donated a stone relief of the Virgin and Child to the Mainz Cathedral of Our Lady in thanksgiving for their safe return (figure 5).17

In Jerusalem, the Peregrinatio pilgrims’ path dovetailed with that of two others who would write their own accounts of the journey. Felix Fabri, a Dominican preacher from Ulm who traveled in another galley on the way east, was on his second trip to the Holy Land, and he would go on to compose four texts about his travels: a Latin account known as his Evagatorium in Terrae Sanctae, Arabiae et Egypti peregrinationem (Wanderings in the Holy Land, Arabia, and Egypt on pilgrimage); a guide to spiritual pilgrims called Sionpilger (Sion pilgrims); an abridged redaction of the Latin account in German; and a rhymed itinerary of his first pilgrimage in 1480.18 Paul Walther von Guglingen, an Observant Franciscan, had made his way to Jerusalem in July 1482, penniless in true mendicant style, and he stayed there for a year at the monastery on Mount Sion, until Breydenbach invited him and Fabri to continue on to Egypt with the Peregrinatio party. He made productive use of his extended stay in the Holy Land, compiling information—albeit strongly and at times vituperatively biased toward his Latin Christian point of view—about the peoples and languages of the region, in particular Muslims and Arabic.19 The text recognizes this when it tags him in the list of pilgrims who made the trip to Mount Sinai as one of two friars, “who know many languages” (137v, ll. 4–6).

Fabri shared a galley with Breydenbach’s group on the voyage back to Venice (158r, ll. 5–9), and Fabri reports that once there, Breydenbach invited him over to his accommodations, where they talked about the planned Peregrinatio and where Fabri had to turn down an offer to return with Breydenbach to Mainz.20 In his Evagatorium, Fabri repeatedly praises Breydenbach and the Peregrinatio, albeit enough to suggest a bit of name-dropping, and Breydenbach returns Fabri’s admiration in describing him in the list of Sinai pilgrims: “a very learned teacher of Holy Scripture and a renowned, serious preacher in Ulm, who has been to Jerusalem before, an experienced father” (137v, ll. 13–15). This testimony suggests that the two authors shared not just a formative journey, but also a common outlook on the legacy of the experience. Fabri’s accounts provide extensive corroboration of the Peregrinatio’s description of events, often filling in details of elements that the disciplined Peregrinatio text mentions only with succinct restraint or passes over altogether.21

Shortly after Breydenbach’s return to Mainz in early 1484, a new prelate, Berthold von Henneberg, was elected by the canons of Mainz Cathedral, and it is Henneberg’s arms that stand at the head of the Peregrinatio text. Henneberg vacated the position of dean of the cathedral chapter to assume his new rank, and Breydenbach was selected as his replacement. In that first year as dean, Breydenbach was also the impresario for another highly influential and visually ambitious book, an herbal called the Gart der Gesundheit (Garden of health), printed in March 1485 by Peter Schöffer, with text assembled by a local physician, Johann von Cube (figures 11, 21).

Throughout his career Breydenbach accumulated numerous additional positions that culminated in these years to signal his growing duties as one of the archbishop’s closest aides. For the cathedral chapter, he administered the largest town in their territory, as well as the goods and finances of the chapter itself, which included their library. Henneberg granted Breydenbach the privilege of traveling to Rome to represent Mainz at the coronation of Pope Innocent VIII in August 1484 and to retrieve the papal confirmation of the archbishop’s election and the pallium for his formal investiture. While there, Breydenbach was given the honorary dignity of apostolic protonotary. In addition, he continued under Henneberg in the office of chamberlain to the archbishop, a role that occasioned his travel to attend state occasions and involved him in the governing of the city of Mainz, both in conjunction with the town council and the courts and in the oversight of the university there. Already in 1477 under a previous archbishop, Breydenbach had presided as chamberlain over the trial for heresy—and conviction—of a member of the Erfurt faculty who had written against indulgences and other doctrines. Breydenbach’s standing in the diocese leaves no doubt that he functioned during the years of the publication of the Peregrinatio in a way that was compatible with the archbishop and his policies. These details of Breydenbach’s biography also explain how he could afford the pilgrimage and underwrite publishing projects, as it is generally assumed, lacking other evidence, that he funded the printing of the Peregrinatio out of his own pocket.

The Role of Erhard Reuwich

Erhard Reuwich of Utrecht has a name, though there is meager biography or artistic history to attach to it. The Peregrinatio repeats that name three times: (1) in the front matter, where Breydenbach’s bringing along a painter promotes his authorial diligence and initiative; (2) in the colophon that identifies Reuwich as the printer; (3) and at the beginning of the second division of the book, where Breydenbach lists the travelers who trekked to Mount Sinai. There he is “the painter called Erhart Reuwich, born in Utrecht, who drafted [hatt gemalet] all the pictures [gemelt] in this book and carried out the printing in his house.”22 His surname refers to the town of Reeuwijk, less than twenty miles west of Utrecht, and painters with this name are recorded in guild rolls and at work in the two local churches. Hillebrant van Rewyjk, active at the Buurkerk between 1456 and 1465 and dean of the guild in 1470, seems the right generation to be Erhard’s father.23

A Solms-Lich family account book records that Count Johann’s brother, who assumed the count’s title after Johann’s death in Alexandria, gave “6 albus” (a small tip) to Breydenbach’s painter and snytzer (carver) after the pilgrims’ return in 1484.24 The new Count Philipp of Solms-Lich would go on to serve at the courts of Maximilian I, Charles V, and Frederick the Wise; to be portrayed by Albrecht Dürer (drawing), Lucas Cranach (oil study), and Cranach’s follower Hans Döring (panel painting); and to patronize the building and rebuilding of local churches and family properties with Döring as his court artist. It is tempting to speculate that he could have begun this career by financing the Peregrinatio as a memorial to his brother, but he was only fifteen years old in the spring of 1484 and is not mentioned in the book. Some scholars have read the term snytzer as “sculptor,” but it can just as easily refer to the making of woodcuts, which require the carving of a woodblock.25 There was usually a division of labor, however, with the draftsman turning his design over to a specialist block cutter, who stood lower in the workshop hierarchy.

The trio of noblemen in the Peregrinatio party were accompanied by an equal number of attendants, as was customary for pilgrims of rank, and Reuwich appears to have traveled in this socially recognizable role. Breydenbach specifies that he booked passage for six from Venice, and while he only names four of the group, Felix Fabri confirms the number in his list of Sinai travelers and identifies the other two: Johannes, called Hengti, steward and expert cook; and Johannes Knuss, Italian interpreter.26 The Peregrinatio speaks of Reuwich as a painter, separate in status from the lords and their servants, and Fabri also singles out Reuwich for mention as a painter.27 Here, though, Fabri describes him as “Erhard, a certain companion, armor-bearer [armiger], and servant to the count.”28 The descriptor armiger may be used here as a mild honorific, as the term traditionally meant a squire, in the sense of a man with his own coat of arms who serves a nobleman without being a knight himself, though not all men who performed such duties were entitled to a family sigil. In recounting the illness of Count Johann, Walther von Guglingen writes that “Johannes the cook and Eckart the servant” wanted to take the first shift sitting vigil at the sickbed during the night the young man died.29 Presumably, then, the gift to Reuwich from the new count was a tip for services rendered during the pilgrimage.

Beyond the illustrations of the Peregrinatio and the Gart der Gesundheit, no other extant works have been definitively ascribed to Reuwich, though he can be reasonably linked through documents to two lost paintings and some surviving painted glass roundels.30 The first is the painting of Count Johann made before the group departed. The second is a panel with a view of Jerusalem that was documented in the eighteenth century hanging in the chapter house of the Mainz Cathedral near an intarsia trunk Breydenbach bought in Venice, presumably for the galley voyage.31 In December 1486, “Master Erhart, the painter” from Mainz arrived in Amorbach with his assistant William. They delivered and installed painted glass roundels for a new administrative building and archiepiscopal residence (Amtskeller) finished under the patronage of Henneberg. Erhart, also referred to as “the glazier from Mainz,” finds mention in the project’s account book six times, and scholars have largely accepted him as Erhard Reuwich.32 Just as woodblock cutters executed the designs of another hand, so too could specialists transfer another artist’s design to glass, and Reuwich may not have to have been a glazier.33 Four of the original windows have survived, showing Saint Martin and the Beggar, the Resurrection, the arms of the archbishop, and the arms of the archbishop’s mother. Overall, the pattern of these commissions suggest an émigré who traveled down the Rhine and found work creating and executing designs in various pictorial media at the court of the archbishop of Mainz, in particular in the personal retinue of Breydenbach.

Not only does the colophon of three editions of the Peregrinatio name Reuwich as the printer, but the German text further specifies that he printed the books “in his house” (137r, ll. 32–34). The books are printed, however, using the type of Peter Schöffer, a printer active in Mainz since he worked with Johannes Gutenberg in the 1450s in the very earliest days of the invention of printing with movable type. Schöffer also had ties to the three printers in Lyons, Speyer, and Zaragoza who received the original woodblocks for use in their later editions.34 When the partnership of Gutenberg and Johann Fust split in 1455, Schöffer joined with Fust, eventually married Fust’s daughter, and then continued on alone after Fust’s death in 1466.

The fact that Reuwich used Schöffer’s type and printed no other books has led scholars to question whether he in fact printed the three editions of the Peregrinatio, particularly the text, on his own press.35 Breydenbach had also worked with Schöffer very recently to produce the Gart der Gesundheit. The possibilities for arranging the logistics and financing of printing projects were still quite fluid, however, so it was not unknown for a printer to earn a fee by renting out his type or other equipment, rather than getting more deeply invested with an ambitiously expensive undertaking. The credit in the colophon may indicate that Reuwich assumed a role that would have been something like executive printer, directing the design of the book, particularly the foldout woodcuts, and overseeing the logistics of printing in Schöffer’s shop. He could be compared also to Lienhart Holle, discussed in chapter 4, who had long-standing ties to the printing industry but only set up shop when he came into possession of some unique luxury visual materials (his uncle’s maps). He published these along with a few other editions before going bankrupt and leaving the trade. For Reuwich, like Dürer after him, the colophon may obscure any number of different possible arrangements, but with the salient result that the artist claims the production credit for himself.

Most of the discussion of Reuwich’s identity has centered around a debate over whether he should be identified with the Housebook Master and/or the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet, the artist(s) behind two bodies of work that are often thought to stem from the same individual. The Housebook Master takes his name from his pen-and-ink illustrations in the Medieval Housebook, a manuscript with an assortment of texts about such topics as medicine, mining, and military strategy produced around 1475–90 for a German noble court in the Rhine region. The Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet created an unusual and inventive collection of drypoints, most of which are held in the Rijksmuseum (figures 6, 7). Several paintings also seem to belong to the Housebook Master’s corpus, namely the double portrait of the Gotha Lovers and two sets of religious painting for churches in Mainz and Frankfurt, and scholars have vigorously contested the relationship among these three groups of works: illuminations, drypoints, and paintings.36 Adriaan Pit made the first comparison to Erhard Reuwich’s woodcuts in 1891: the mounted Turk in a print by the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet resembles the zurna-and drum-playing riders in the Peregrinatio’s Ottoman military band (figures 7, 8).37 Since then, a meticulous comparison of the style and imagery of the Peregrinatio’s images with the works attributed (tentatively and firmly) to the Housebook Master and/or the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet has fueled even more discussion.

Through this debate, two arguments have been put forward to support the Masters’ identification as Reuwich. First, the coincidence of the artists’ biographies provides circumstantial evidence. Certainly, these personalities were active in the Rhine region at the same time, working for the lower nobility. The patron of the Gotha Lovers, for example, was most likely Count Philipp von Hanau-Münzenberg, who traveled with Breydenbach’s handwritten pilgrimage instructions and who in 1490 would become the father-in-law of Count Johann’s brother, the new Count Philipp von Solms-Lich.38 An artist of Reuwich’s quality, entrusted with a project like the Peregrinatio, should have a larger oeuvre, the thinking goes, just as the Masters should have a name.39 The second argument discerns evidence of a single hand in the similarities of style and motif in the Masters’ work and Reuwich’s illustrations for the Peregrinatio and the Gart der Gesundheit. Reuwich’s hatching—most obviously the fuzz on the jaw of the lady of the Peregrinatio frontispiece—recalls peculiarities of the Master of the Amsterdam Cabinet’s drypoints, where the modeling is built up through short strokes that leave a sketchy corona around the figure. With both Reuwich and the Master, this hatching suggests an artist attempting to transfer the techniques of a draftsman to a new print medium without the training in engraving that most late fifteenth-century intaglio printmakers took from their background as goldsmiths or sons of goldsmiths.

This type of analysis has focused on the question of who did what: first, whether aspects of the images of Peregrinatio are too skilled or coarse to attribute to one or both of the Masters; then, as a corollary, whether Reuwich himself drew each image in its entirety from life, as the Peregrinatio text claims. And if not, who did? For example, if Reuwich composed the Peregrinatio’s expansive spaces, namely the image of the forecourt of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and aspects of the city views, then he had a better grasp of perspective than the Masters.40 At the same time, if the deft handling of the frontispiece is contrasted to the Peregrinatio’s other images of people, then the discrepancy can be explained if the execution of that introductory tour de force had been delegated by Reuwich to the Master.41 (These comparisons largely ignore the presumed, but unknown, intervention of the block cutter, upon whose skill the full printed success of the drawn design hinges.)

When Hans Tietze and Erika Tietze-Conrat attributed the View of Venice to a lost original by Gentile Bellini and gave Bellini’s copy of the Peregrinatio’s Saracens priority, they took another tack, recognizing early on in 1943 that Reuwich seems to have relied on others’ designs.42 Some scholars have more loosely speculated that Reuwich could have found a model for the Map of the Holy Land with View of Jerusalem in the Franciscan library at their monastery on Mount Sion.43 The Tietzes’ suggestion lay largely dormant, though explicitly rebutted by Jürg Meyer zur Kapellen in his monograph on Gentile Bellini, until recently revived by Frederike Timm with new research.44 She has analyzed Reuwich’s View of Venice and several other city views to show that they omit conspicuous new buildings and fortifications and, therefore, are likely based on acquired images drawn earlier. From there she argues that the advanced artistic elements in most of the images could be based on a conjectural cache of Venetian drawings.45

Timm goes too far in proposing that most of the frontispiece, all the views except Rhodes, the image of Saracens, and the illustrations from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher came from a single cache of Venetian sources out of the Bellini workshop.46 With its arbor of gnarled tracery and its raucous foliage, its Venetian woman and its putti, the frontispiece is one of the most tantalizingly hybrid works of its day, though nonetheless clearly one invented by a Northern artist. Neither the Saracens nor the View of Jerusalem was originally drawn by a Bellini, as will be examined in chapters 3 and 5. The depiction of a just completed madrasa demonstrates that the view was put together by an artist who had seen the Holy City in 1483, the year of Reuwich’s visit. Chapter 4’s investigation of the map shows the integration of elements particular to the pilgrimage and the Peregrinatio that also would not have come from a single found model. Nevertheless, Timm’s basic point and the attempts of earlier scholars to reattribute the Peregrinatio illustrations are all well taken: Reuwich did not draw every image in the Peregrinatio from scratch on-site, as the text would have us believe.

More fundamentally, however, the discussion to follow steps away from this method of analysis that seeks to distinguish original work from researched material in order to assign Reuwich an oeuvre that can then be connoisseurially assessed against other prints and drawings. Reuwich relied upon a heterogeneous array of sources, as the analysis of the map in particular demonstrates, while interpolating his own observations, visually collating the collection, and translating them into woodcuts. It is for this effort that he is properly described as the artist of the Peregrinatio. Whenever Reuwich is referred to here as the artist of the book, that language acknowledges the artistic value of that process. The phrase “Reuwich’s image” will refer to a woodcut printed in the book or to the presumed final design for the woodcut that was transferred to the block, not to any sources that may have informed the print or been copied into it. They are not the same thing. To dwell on the attribution of the sketches is to conflate authorship of the original drawings with the rest of the intellectual and material effort to produce the Peregrinatio. To dismiss Reuwich as draftsman elides the achievement of the Peregrinatio as a printed book. The value of the work lies exactly in the unusual, Peregrinatio-specific procedure for designing and producing the printed whole. Hunting for the origins of the Peregrinatio’s mimesis has obscured an appreciation of the book’s other success as multimedia bricolage.

Instead of asking who first sketched the images of the Peregrinatio, we can ask how it is that we and the Peregrinatio’s earliest readers came to believe that Reuwich produced them himself based on on-site observation. We believe it because artist and author designed the Peregrinatio to convince us that it is so. Why and how did they do that? No matter their origin, the Peregrinatio’s images were highly original to their readers. How and why did author and artist achieve that novelty? The answers to these questions point directly to the concerns and strategies at the heart of their project to rethink the making of a book. The creators of the Peregrinatio do not take their readers’ confidence for granted; they labor to earn it. As we watch their efforts, we witness the formulation of mechanisms by which images claim truth and authors assert authority—a process stimulated by print.