Читать книгу Becoming Tom Thumb - Eric D. Lehman - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеAT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM

Museums in the United States were still experiencing an uncertain childhood. Were their primary purposes to provide academic settings for elites? Education for the public? Entertainment? Or were they simply “repositories” of curiosities, as Dr. Johnson defined them in his 1755 dictionary? The first small American museum was founded in Charleston, South Carolina in 1773, followed by a variety of societies and academies interested in promoting the development of knowledge, all with varying levels of capability and finances. Public funds or private donations for institutions arrived haphazardly and rarely. For the next century, museums continued in this state of flux, with respected institutions like Boston’s Gallery of Fine Arts promoting an exhibition in 1818 of engravings by Hogarth, and a year later featuring a pair of dwarfs called “The Lilliputian songsters.”1 This was further complicated by the attitude of a public which attended museums primarily for entertainment and not enlightenment. Talking, running, and behaving badly was the norm in all museums for over a century, while owners and newspapers fought a long attrition against these “plebian” attitudes. Charles Willson Peale was forced to post a sign at his ornithological exhibits that read “Do not touch the birds as they are covered with arsenic Poison.”2 And as late as 1891, when the Metropolitan Museum of Art opened its doors on Sunday afternoons, they had to collect canes and umbrellas at the door to ensure that none would be used to “prod a hole through a valuable painting, or to knock off any portion of a cast.”3

Funding, audience, and presentation have always been challenges for museums all over the world, but these issues were particularly acute in the rapidly changing society of early America. Most museums of the time depended solely on an increasingly urban, middle-class population to support them through admission fees. In 1784 portrait artist Charles Willson Peale opened a “museum” in his large home in Philadelphia, using only his own limited resources. Nevertheless, this business grew rapidly in what at the time was America’s largest city, becoming the most important early American museum. Two years later The Peale Museum had taken up residence near Independence Hall, and was packed with paintings, taxidermy, and collections of dinosaur bones. Peale tried to walk a fine line between “rational amusement” and enlightenment for his middle-class patrons, using magic mirrors, speaking tubes, and other gadgets to keep people’s interest. Founded in 1814, his son Rembrandt’s Baltimore establishment at first provided a “serious” art museum for patrons, but when his brother Rubens took over, he switched to a “side-show” style of museum, containing various illusions, automatons, and wax figures. He did the same with his father’s Philadelphia museum, and expanded the franchise to New York in 1825.4

Another museum that followed this model was Scudder’s American Museum, which had its small beginnings in Manhattan as early as 1795, and in 1830 had relocated to a five-story building at Ann Street and Broadway, across from St. Paul’s Chapel. Less than two years before he met Charles, an optimistic P. T. Barnum had purchased Scudder’s. By this time competition from Peale’s, exacerbated by financial panics and fires, had driven Scudder’s to near worthlessness. The current owners asked a mere $15,000 for the extensive collections. In a move of contract legerdemain, Barnum played Peale’s Museum proprietors for fools to the tune of $3,000 by agreeing to manage the American Museum for them if they purchased their rival. At the same time he signed a contract with the owners of Scudder’s American Museum to purchase it if Peale’s defaulted. When it did, Barnum promptly bought it out from under them at $12,000, keeping their management fee as well.

Inside, the museum was an astonishing mixture of natural wonders, wax figures, paintings, inventions, and curiosities, and the enterprise expanded rapidly under Barnum’s management, with his constant eye for the “draw.” To the “legitimate” collections of such things as ancient coins and rare minerals, he added objects as strange as a preserved hand and arm of a pirate and a large hairball taken from the stomach of a pig. He also brought in numerous live exhibits and acts, which were showcased in galleries or dioramas, or performed in the Lecture Room, or both.5 Colorful pictures of exotic animals and other curiosities were displayed between each of the one hundred windows, American flags flapped in the wind high above the street, and New York’s first spotlight swept across Broadway from a rooftop turret.

Though patrons could see the entire collection for just one small fee, Barnum devised other ways to gather their money. Brightly colored concession stands situated throughout the hallways sold books, photographs, and a variety of fish tanks. As the decade of the 1840s passed, visitors would find glassblowers demonstrating their art and selling their baubles, or fortune-tellers and phrenologists predicting fates. A downstairs oyster saloon brought in fresh bivalves, while on the roof a picnic garden allowed guests to bring their own lunch or purchase ice cream and cake. Barnum even installed a taxidermist’s shop, where visitors could bring their recently deceased animals, and at the end of the day pick up their stuffed and mounted pets.6

Charles appeared at the Museum for the first time on Thanksgiving Day, 1842, which that year fell on December 8.7 Horace Greeley’s new daily paper, The Tribune, reviewed this premier exhibition, saying, “General Tom Thumb, Junior, the Dwarf, exhibiting at the American Museum, is by far the most wonderful specimen of a man that ever astonished the world. The idea of a young gentleman, eleven years old, weighing less than an infant at six months, is truly wonderful. He is lively, talkative, well proportioned, and withal quite a comical chap.”8 Other glowing reviews followed, and the increased ticket sales not only kept the American Museum in business, but by January 2, 1843, the rival Peale’s New York Museum was ruined. Barnum promptly bought his second museum and kept it open as “competition,” taking the profits from both.9

Even at Charles’s first appearance, this reviewer saw him as “comical,” though Barnum had not had a chance to “train” him yet in the art of humor, as he claims to have spent long hours doing later. This fact points clearly to inborn comic talents as part of his character and not something “grafted on” as later critics sometimes tried to establish. Other early reviewers mentioned his poise and intelligence, without knowing he was six years younger than advertised. Colonel James Watson Webb of the Courier and Enquirer called him a “little gentleman” and commented on his “dress and manners,” saying “he is a sight worth going a great way to see.” Philip Hone, the wealthy former mayor of New York, saw Charles a few months later. He writes wonderingly:

I went last evening with my daughter Margaret to the American Museum to see the greatest little mortal who has ever been exhibited; a handsome well-formed boy, eleven years of age, who is twenty-five inches in height and weighs fifteen pounds. I have a repugnance to see human monsters, abortions, and distortions … but in this instance I experienced none of this feeling. General Tom Thumb (as they call him) is a handsome, well-formed, and well-proportioned little gentleman, lively, agreeable, sprightly, and talkative, with no deficiency of intellect … His hand is about the size of half a dollar and his foot three inches in length, and in walking alongside of him, the top of his head did not reach above my knee. When I entered the room he came up to me, offered his hand, and said “How d’ye do, Mr. Hone?”10

At the time, Barnum lived in a converted billiard hall next to the museum, and Charles and his parents lodged on the fifth floor of the museum itself with some of the other performers. He started on exhibition in the “Hall of Living Curiosities” at the museum, where he immediately began talking to the curious visitors, evidently overcoming any bashfulness quite quickly. He graduated to the so-called Lecture Room, actually a large theater. On the stage, Charles began with easy skits and tricks. Barnum’s first idea did not require Charles to act a great deal; the “Grecian statues” performance involved Charles posing as great heroes and figures from history, the contrast of size and appearance being the primary spectacle. His small body held taut and poised with club upraised in the attitude of Cain about to kill Abel, or with spear ready to fly as Romulus, drew attention to the fact that this was not a weak, helpless child, but a “man in miniature” as advertised. At both the shows and private parties he would sometimes hold a small cane with two hands and let a man carry him while hanging from it, again demonstrating his strength but this time contrasting it with the size of an ordinary man.11 A writer from the Brooklyn Eagle recalled that Charles “laid hold of a stick which I grasped in the centre and I carried you [Charles] round the room.”12 Highlighting Charles’s size was meant to surprise and shock the audience whenever possible. Charles himself described one of these early tricks in an interview:

At that time I was so small that Mr. Barnum could easily hold me in the palm of his hand. A style of overcoats … known as box-coats, were then in vogue. They had large side pockets with flaps over them. Mr. Barnum wore one of them in winter. I could get in one of the pockets of it, and by doubling myself up the flap would fall over the mouth of the pocket, concealing me from view. It was a favorite trick of Mr. Barnum’s to place me in the pocket of his box-coat and appear in the hall at about the time set for the opening of our entertainment. The people in the audience would come about him, exclaiming “Where is the general, Mr. Barnum? Here it is time for the exhibition to open, but he is not about.” Mr. Barnum would appear to be greatly surprised, and would then call out: “General Tom Thumb! General, general! Where are you?” I would then respond: “Here I am, sir,” emerging from his pocket at the same time. It was a great act, I tell you, and used to take immensely.13

He also showed an aptitude for music, and began learning songs. One of the first was the classic Revolutionary Era melody, “Yankee Doodle.”

Yankee Doodle came to town

Riding on a pony

Yankee Doodle keep it up

Yankee Doodle Dandy

Mind the music and the step

And with the girls be handy.

He would sing versions of this in his high treble voice for at least the next twenty years, changing the lyrics as the situation demanded. James White Nichols of Danbury said in his diary that Charles’s singing voice “was to me purely original. I could bring no human voice I had ever heard in comparison with it. It bore more resemblance to the voice of a bird; sweet, clear, shrill, and effective, it captivated his hearers with its melody, while it astonished them with its strength.”14 Along with musical skills, he showed an aptitude for memorizing rehearsed speeches, dialogues, and song lyrics far beyond his actual age. A well-dressed “straight man” asked him questions while he stood in the costumes and posed. One of these exchanges features the “Doctor” acting as questioner:

DOCTOR: What dress is this?

GENERAL: It is my Oxonian dress. (Puts on dress)

DOCTOR: It is the dress presented to the General by the students at Oxford. What do you represent now?

GENERAL: A fellow.

DOCTOR: I understand—a fellow at Oxford.

GENERAL: No, a little fellow.

DOCTOR: Did you have any degrees conferred upon you?

GENERAL: Yes, sir, Master of Hearts.15

When the Grecian statues were not enough to keep him or the audience happy, Charles graduated to mock battles with “giants,” starting with the French M. Bihin and Arabian Colonel Goshen, who Barnum hired earlier that year. That summer, on July 8, Charles appeared at Peale’s Museum with a “giant girl,” agreeing in “the kindest manner” to visit her three times during the day, to show the public the “most wonderful contrast.” Other plays and skits followed, which included a gender switch to “our Mary Ann,” as well as fabricated and exotic backgrounds and status enhancement, of which the title “General” was the most obvious example.16 All these techniques were used to promote Charles, and of course were not only common amongst little people, but actors, singers, and performers of all sorts.17 This is the business of entertainment. Barnum used these techniques at the beginning because he thought he had to. But it quickly became apparent that what he had on his hands was not another humbug, but an actual attraction.

After the initial reviews came out, he increased Charles’s salary to $7 a week for a year, $3 of which went directly to Sherwood, who acted as a sort of gofer for Barnum during this period. Lodging and travel were also paid by Barnum, however, and a bonus of $50 was promised. Sherwood and Cynthia signed this contract on December 22, 1842.18 Along with other doubts, the showman remained terrified that the four-year-old child would increase in stature, and seemed relieved whenever he reported to his friends in letters that he had not. Later, he reports with joyous humor to his daughter Cordelia, “He don’t grow a hair, but the little dog grows cunning every day.”19

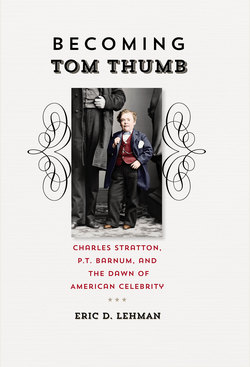

Overlaid by the contract his parents signed with Barnum, this is the first known photograph of Charles at age four, sitting next to a man once thought to be his father, Sherwood. However, this is in dispute. The oldest portrait photograph of a person known to exist is only three years older than this one. Collection of The Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

For those who saw Charles up close, there was no question as to his remarkably small size. However, during performances on stage, an unfortunate lack of scale was created. James White Nichols mentioned this illusion, and Barnum’s solution, saying: “When standing alone on his platform, it was remarked by many, he did not look so small as they had anticipated. The truth was he appeared somehow, in that position, magnified above his real size. The showman understood this too, and by bringing him down and placing him beside the smallest child which could be found present and able to stand, made his extreme littleness in the contrast more vividly apparent.”20 All observers commented on Charles’s “perfect” appearance as a very handsome, “fully-grown” man shrunk down to the size of a baby. An 1843 quote by Dr. J. V. C. Smith in the Massachusetts Medical Journal is also often quoted to support this: “He appears now as fully developed as he ever will be. Of all dwarfs we have examined, this excels the whole in littleness. Properly speaking he is not a dwarf, as there is nothing dwarfish in his appearance—he is a perfect man in miniature … We gaze upon his little body dressed out in the extreme fashion of the day with indefinite sensations not easily described, partaking of that class of mixed emotions which are felt, but which language has not been able to explain.”21 A few years later, the Washington Union remarked, “Instead of a spectacle of deformity, you are surprised to see one of the most graceful and well-proportioned miniatures of a man which the imagination can conceive, with fresh complexion, delicate hands and feet.”22 This focus on “proportion,” made much of in the early years as a promotional strategy, was taken seriously by scientists of the day.

Charles’s obvious intelligence was also a direct challenge to craniometry, a popular “science” at the time. This usually involved a process of measuring the size and shape of a skull, including bumps and anomalies, and judging by these measurements the propensities, sentiments, and mental abilities of a person, which were supposedly located at specific points around the brain. A “phrenologist” examined Charles’s skull, and reported that the brain is “the smallest recorded of one capable of sane and somewhat vigorous mental manifestation,” saying further that “Gen-eral Tom Thumb is, then, I repeat, a case of un-usual interest to the phrenological world.”23 What he is not saying with this understatement is that Charles’s existence completely refuted the theory of linkage between brain size and intellect, an idea that unhappily continued to linger until the twentieth century, influencing various racial supremacist and imperialist philosophies.

One silent tribute to the boy’s precocious brainpower was the fact that so few educated adults questioned the inflated age Barnum tagged him with. Ambassador Everett certainly did not, and neither did any of the European nobility he encountered over the next few years.24 His physical condition was also important, as “dwarfs” were often considered sickly or unfit. He was advertised as having “always exhibited the most perfect health.”25 The Baltimore Sun noted “We cannot describe the sensation with which one looks upon this diminutive specimen of humanity. Were he deformed, or sickly, or melancholy, we might pity him; but he is so manly, so handsome, so hearty, and so happy, that we look upon him as a being of some other sphere.”26 And in fact this seems to be the case and not just propaganda. Until 1883 there is only one report of Charles being too ill to perform, despite working long hours, traveling constantly, and smoking daily cigars.

Nevertheless, he had to prove his health repeatedly to a society that thought of dwarfs as perpetually weak and sickly. And although child actors were fairly common, concern for their health was just as prevalent as it is today. When child actor Master Betty had burst onto the English scene forty years earlier, a number of people, including Prince William, Duke of Gloucester, the brother of George III, tried to make sure that acting five times a week in “deep tragedies” was not taking its toll on the boy’s health.27 Since Charles was even younger and much smaller, this issue was no doubt brought up by members of the audience quite often. To preempt this, the showman, whether Barnum or a surrogate, would usually bring it up during the performance, giving “general statements and remarks on the little General’s health,” along with assuring the audience that no “signs” or “omens” accompanied his birth. He would stress the happiness and appetite of the child, citing his “uncommon power of enduring fatigue,” despite being “task’d with constant performance through the whole day, almost, without rest.”28 Along with reassuring both the prejudiced and genuinely concerned, Charles and his managers needed to carefully turn whatever pity or sympathy the audience might have into wonder and amusement. No one wanted the audience to go away distressed or unhappy.

While the success of “Tom Thumb” was bringing in huge sums of money for Barnum, the showman continued his media assault, combining exaggeration with truth. Many of his early stories about Charles might be somewhat embellished. One suspicious anecdote took place during his dinner with Colonel James Watson Webb in New York. Charles stood on the table while the turkey was being carved, and knocked over a tumbler of water. This event seems quite reasonable, but his quick response, that he was afraid he might fall in, sounds invented, as does when he promptly drank the health of all present in a glass of Hungarian wine.29 However, like most of Barnum’s stories, there was a grain of truth in it, and the rehearsed dinner table joke was certainly repeated at other houses over the years.

Charles was clearly the biggest draw for visitors at the American Museum, and sending him away meant a risk. Barnum knew, however, that money could be made elsewhere. Throughout the first year, the boy traveled to different places around New York and New England accompanied by Barnum or his business manager, Fordyce Hitchcock. From May to June 1843, Charles spent six weeks doing his “statues” at the Kimball Museum in Boston, accompanied by Hitchcock and his father. Apparently during all that time Sherwood did nothing but sit in his hotel room, even when Senator Daniel Webster and President John Tyler came to Boston on June 17 to speak at the anniversary of Bunker Hill, amidst a huge celebration.30 This strange incident foreshadowed Sherwood’s increasingly erratic behavior as the years passed. Luckily, during the tours of theaters and halls in the Atlantic cities that year, Sherwood began acting as ticket-seller, and this job seemed to please him, especially handling the money.

Detailed accounts of these exhibitions are rare, but James White Nichols gives a thorough description of one of these “levees” in Danbury, Connecticut a few years later. Though by that time Charles had advanced in skill and was putting on plays and more complicated performances, apparently he occasionally fell back on the basic formula, only changing the impersonations or characters to suit the occasion. On a Monday in autumn, Nichols found handbills scattered around town advertising a show the following week, and by the day of the exhibition had composed a hilarious poem about the incredible buzz around town, “the streets were unpeopled, all business was dumb, absorb’d in the interest of Gen’ral Tom Thumb.” On the day of the performance the main room at the city hall swelled to capacity, with between four hundred and five hundred people standing wall to wall. A stage had been built over the judge’s seat, with another gold-railing platform raised three feet above.

Mr. Webster, the “conductor” carried the “The Little General” into the room high over his head and set him on the stage. Charles scrambled up a miniature flight of steps to the platform “with the agility of a little squirrel” and bowed to the audience, saying “Good afternoon, Ladies and Gentlemen!” A selection of costume changes followed, with Charles becoming a professor at Oxford, a Spanish dandy, a sailor, and a Bowery b’hoy from New York. Most of the effect was gained by a simple change of hats: narrow brim for the Spaniard, battered white hat for the b’hoy, and a mortarboard for the Oxonian. Mr. Webster would ask him about the Oxford cap, for example, and Charles would answer with a joke: “One of the hats we read of!”

He sang songs as each of the characters, “swaggering and staggering around the platform amid rapturous shouts of applause.” Dressed as a sailor he danced a hornpipe before taking his first “break” only to emerge as Napoleon, with “indescribable style” walking in a “meditative and abstracted ramble” and taking snuff in the manner of the French general. Then he impersonated Frederick the Great of Prussia as an old man, with “stooping form,” “tottering gait,” “shaking hand,” and “unsteady head.” He changed clothes again, appearing in a tight white bodysuit and imitating Cupid with bow and arrow, a frightened slave, Ajax, Sampson, Cincinnatus, Cain slaying Abel, Hercules, the Gladiator, and more. Nichols writes wonderingly, “In all these his position was so true to the originals—his firmness of nerve so conspicuous—that for the time being the eye was ready to acknowledge him the true creation of the sculptor chiseled out of the real stone.”

He finally appeared in the elaborate costume of a Scottish Highlander, which looked “perfect in every particular,” including a bonnet and plume, royal Stuart plaid “united by a most gorgeous clasp” and a coat of arms, a dirk and claymore, powder horn, pistols, and “skene d’hu” or deer knife. This was a lot to carry for such a “little body,” and “yet he moved about perfectly easy and untrammel’d by the uniform.” Of course in this outfit he danced a highland fling and sang a Scottish song, “all which was done in his usual sweet and inimitable style of acting.” Throughout all these costume changes, Mr. Webster fed him innocent questions, as a straight man setting up Charles to deliver his jokes.

“What do you call that, General?” “A claymore!” “What do you do with it?” This was answered by assuming an attitude of defiance and flourishing it in a warlike manner toward him. Again: “What is that General?” “That is my skene d’hu!” “What do you do with it?” “Skin deers!” “When do you skin them?” “When I catch ’em!” with a quickness of expression which brought out a laugh from every corner of the house.

Nichols echoes almost every other contemporary account when he insists: “Of all the innumerable host who attended these levees, I saw or heard no one who grudged their money or wished it back in their pocket, and the great curiosity still a stranger to their eyes. All united in the declaration that he was the most extraordinary sight they had ever beheld, and a more remarkable specimen of humanity, probably, than it would ever be their happiness again to look on.”31 Nichols went home to tell his wife what he had seen, and she promptly dragged him back with her to the evening show.

Charles’s physical and verbal comedy skills and his ability to memorize and adapt were on constant display to an appreciative public. Nichols expresses amazement at the boy’s comic timing, his muscular control, and his singing skills. All this was a tribute to the tiny but fertile brain that was being cultivated to its full capacity. It was startling even to Barnum that such a young boy could learn so much, and so quickly. “He was an apt pupil with a great deal of native talent, and a keen sense of the ludicrous. He made rapid progress in preparing himself for such performances as I wished him to undertake and he became very much attached to his teacher.” Barnum also claimed that “he was in no sense a spoiled child but retained throughout that natural simplicity of character and demeanor.”32 Other accounts support Barnum’s analysis. That may be the most remarkable fact of his career: no one ever reported that Charles developed an ego to match his fame.

Charles’s early career as a child star hinged on his posed portrayal of various characters, from Cain to “Our Mary Ann.” Photo by Paul Mutino. Collection of The Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

But not everything Charles learned from his experience with Barnum was positive. When asked by the showman what he wanted as a present after making him so much money, Charles only asked for a ball of twine. With it, he created a primitive trap by tying it to chair legs and whatever else was available. Barnum or the other adults would walk into the room and pretend to trip over it, a result that would cause Charles to “laugh and scream with such delight as to cause him absolutely to roll upon the floor and shed tears of joy.”33 His gleeful reaction to the apparent harm caused by this sort of devious trick is perhaps easily explained as the act of a young boy playfully pushing his boundaries. Or he could also have been unconsciously or consciously acting out against the parents and mentor who trapped him in a life of work at such a young age. In later years, everyone, especially his wife, described him as the gentlest, most accommodating person, and it is surprising his strange upbringing did not lead him to continue on a path of bullying and callousness.

More troubling is a story the showman related in July 1844 about one of Tom Thumb’s early exhibitions in London, which a well-dressed black gentleman happened to attend. Only a year before, the first “blackface” performance had appeared in New York’s Bowery Amphitheater at the same time Charles was appearing at the American Museum. Blackface actors would apply a mask of burnt cork and act as racial stereotypes to humor the all-white audiences. Building on earlier blackface comedians and singers, as well as “whiteface” clowns, Dan Emmet’s Virginia Minstrels caricatured African-American behavior and speech with malapropisms and rhetorical absurdity, gave mock sermons and political orations, sang plantation songs, and lampooned both black and white cultures. In the decades before the Civil War, this “blackface minstrelsy” became one of the most popular forms of entertainment in America.34 During the mid-1840s Barnum incorporated some of these “minstrel” songs into Charles’s act, and related that in this performance:

I made General Tom Thumb sing all the “nigger songs” that he could think of and dance Lucy Long and several “Wirginny breakdowns.” I then asked the General what the negroes called him when he travelled south. “They called me little massa,” replied the General, “and they always took their hats off, too.” The amalgamating darkey did not like this allusion to his “black bredren ob de South,” nor did he relish the General’s songs about Dandy Jim, who was “de finest nigger in de county, O” and who strapped his pantaloons down so fine when “to see Miss Dinah he did go.” The General enjoyed the joke and frequently pointed his finger at the negro, much to the discomfiture of “de colored gemman.”35

The fact that a prominent New York paper felt comfortable publishing this article shows that derogatory views were not unusual, or even controversial, amongst Americans, including urban northerners, at the time. As any child does, Charles picked up the prejudices of the adults around him, and this disturbing incident is a sad commentary on learned behavior. That the mocking wit Charles included in his act should be pointed at the black man in the audience is not surprising, though certainly disappointing and distasteful. Barnum would perhaps redeem himself for incidents like this later in life, when he became a passionate abolitionist and joined the Connecticut legislature specifically to vote for the rights of African Americans. Charles himself acted in an abolitionist play as a teenager, and seems to have dropped the “nigger songs” like Old Dan Tucker and Dandy Jim from his act shortly after.36 Though other comedians continued to use blackface minstrelsy as a way to poke fun at African Americans throughout the Civil War and after, Charles seems to have used racially charged humor less often than his contemporaries, despite this offensive incident.

By the end of their first year together, Barnum probably began to understand how much of his success was wrapped up in Charles’s performances and that while he was making this “dwarf” a fortune, the dwarf was doing the same for him. Success builds on success, and before “Tom Thumb” he had only had minor victories and major failures, with somewhat profitable fakes like the Fejee Mermaid and Joice Heth, and forgettable hoaxes like the wooly horse and a cherry-colored cat. His much-anticipated buffalo hunt across the river in Hoboken was a hilarious failure, although he managed to make a small profit from it.37 As a Pennsylvania newspaper said twenty years later, Charles was “perfectly formed, graceful in every movement, with a shrewdness and wit worthy of his country … the public found in Tom Thumb a reality—nothing of the wooly horse or the Fejee Mermaid school about him; no wonder the General should attain such popularity.”38 Barnum was discovering already that there was little need for exaggeration with “The General.” People expected a humbug, a baby dressed in adult clothes or a mirror illusion, but when they saw him their disbelief evaporated, and suddenly the world was full of wonders again. Unlike the many other “curiosities” that Barnum had championed, Charles Stratton was real.

The next step was to conquer Europe, where an entirely different audience awaited. After a year showing in New York and northeastern America, the departure date was set for a few days after his sixth birthday, in January 1844. The Tribune praised Charles’s appearances before he left for England, and the Evening Post urged, “A few hours more remain for General Tom Thumb to be seen at the American Museum, as the packet in which he has engaged passage to England does not sail to-day in consequence of the easterly winds now prevailing.”39 On one day alone, fifteen thousand people swarmed through the doors of the Museum to see Charles before he sailed, and continued to buy tickets even on the auspicious morning of his actual sailing, January 19.

At noon he was escorted by the City Brass Band and thousands of other New Yorkers to the docks, where he boarded the steamer Yorkshire with his parents, Barnum, and possibly his tutor Professor Guilladeau, a French naturalist.40 On the passport application he is listed as twenty-two inches high, fifteen pounds, and as Charles S. Stratton, alias General Tom Thumb. A few days later in the same passport register it says “Genl. Charles S. Stratton,” a blend of identities that presaged troubles to come for the boy entertainer.41 But perhaps his role-playing was not as much a problem for him as we might imagine. We often give too little credit to children, who slip between the personalities of make-believe without effort, and whose imaginations are usually more fertile than adults. He remained “Charles” to the people of Bridgeport, to his friends and family, and later to his wife. But to everyone else he was now General Tom Thumb, for forty years one of the most recognizable names in the world.