Читать книгу Becoming Tom Thumb - Eric D. Lehman - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPRINCE CHARLES THE FIRST

In England, Charles’s comedy developed further, becoming part of a new tradition of “Yankee” characters. Although this Yankee personality would enter literature in the novels of Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne in the following decades, it seems to have first been popularized by comedians on the stage. The term was already used by foreigners to describe all Americans, perhaps because northeastern traders were the most frequently encountered. Comedies in early America had featured characters based on these New Englanders, with Royall Tyler’s The Contrast of 1787 the earliest extant play to incorporate “the Yankee” as an important character. But it was not until the 1820s that the type began appearing with regularity. Ironically the first comedian to succeed with this persona was an Englishman, Charles Mathews, an outstanding mimic who created characters that mocked the Irish, French, German, Dutch, and his fellow Englishmen. He used anecdotes, imitations, and songs in dialect to keep the audience amused, and writers like Washington Irving and Samuel Taylor Coleridge praised his talents. In 1824 his three-and-a-half-hour satirical travelogue, Trip to America, set the perceptions of the English public for decades, although the American comedians who followed him would take a slightly less partisan approach to the material.1

From 1826 to 1836 New Yorker James Hackett took this Yankee character to the London stage. He described the character as “enterprising and hardy—cunning in bargains—back out without regard to honour—superstitious and bigoted—simple in dress and manners—mean to degree in expenditures—free of decp.—familiar and inquisitive, very fond of telling long stories without any point.” George Hill of Boston had given an authentic New England flavor to the role in the late 1830s, touring the British Isles between 1838 and 1839 as the best and most famous American comedian known there before the arrival of Charles Stratton. Called “Yankee Hill,” he performed in solo “stand-up” acts and acted in melodramas like Samuel Woodworth’s pastoral comedy The Forest Rose, which sparked an entire genre of Yankee plays to accompany the stand-up comedy routines.2 Barnum himself had already adopted, or perhaps actually embodied, this Yankee character. In later years his solo performances would make great use of its homespun flavor and dry wit, but for the moment he was content to play the straight man to his protégé.

Comedians like James Hackett and George Hill used many characters, not just the Yankee, and Charles did the same. However, all were associated most strongly with this imitation, which represented Americans to Europeans. But not everyone in England thought the “Yankee dwarf” spectacular at first. The London News complained that this “little monster” was “proof of the low state” of theater in the country, though they still faithfully reported his events.3 The paper would change its tune further following his visit to Queen Victoria. After that, nothing could stop the British public in its hunger for the little marvel, and they rushed to London’s Egyptian Hall to see him for a full shilling a head. In 1844 the Egyptian Hall could be found in the tangled mesh of brown streets north of St. James’s Park on Piccadilly. At various times it was also called London Museum and Bullock’s Museum, and housed an average of 15,000 items. The trapezoidal face featured pillars, statues, and elaborate carved cornices, giving it the appearance of an Egyptian temple, and the interior contained a number of rooms for displays and appearances.

Painters who practiced their techniques by copying the intricate art and architecture were frequent visitors to the museum, and they sketched Charles several times while at the hall. The images of him at this age show a cheerful child, with the appearance of confidence, if not its full reality. There is a hint of mockery in his eyes, and a hint of uneasiness in his poses. Barnum created souvenir medals based on one of the sketches, featuring Charles standing on a table leaning against a stack of books. Around the medal image read, “Charles S. Stratton Known as Genl Tom Thumb 25in High” and on the back it stated imperiously, “Under the Patronage of the Queen and Court of England” with “Pub by P.T. Barnum American Museum New York 1844” around the edges. In the middle the text included: “Genl Tom Thumb Born Jan 11, 1832 at Bridgeport, Connecticut U.S.A. At his birth he weighed 9lbs 2oz And was a handsome, hearty, and promising boy. He Increased in size and weight Til 7 months old and then weighed 15lbs and measured 25in since which time he has not increased in size and weight is perfect and elegant in his proportions and has always been in good health.”4 In America, Charles had been “English,” but here he was proudly a “Yankee,” since Bridgeport was now the exotic locale. What is more interesting is that Barnum included Charles’s real name.

Along with souvenir medals, Charles carried small glazed calling cards emblazoned with “General Tom Thumb” in Gothic lettering.5 Also for sale were game counters with his image on one side and “Liberty” on the other, glass paperweights with his visage embedded in it, and more. During the performance he wore special clothes made for him by Gillham Brothers, such as a tiny brown velvet jacket with brass buttons. He hopped on tables and chatted with people until enough new visitors arrived, when he would sing and dance, or tell his “history.”6 James Morgan of Liverpool wrote “General Tom Thumb’s Visit to the Queen of England at Buckingham Palace, 1844” to the tune of Yankee Doodle, of course, and he sang this new version to the delight of the English public.7

The room where Charles “exhibited” in the afternoons was jammed with over a thousand people almost every day. Season tickets were available for three shillings, and some ladies apparently took advantage and came back day after day, gathering his “stamped receipts,” or kisses that he gave out when you bought a souvenir. Students at a military school in Chelsea talked about the Yankee celebrity so much that finally the schoolmasters marched the three hundred boys through the cobbled streets of London to see him at the Hall.8 The boys formed a “hollow square” around the four sides of the room, and sang “God Save the Queen,” a recital which Charles pronounced “first rate.” Then Charles sang his own songs, and this fascinating exchange thrilled everyone. Rumors and tales about him flew around the city. The newspapers even reported his elopement with a “lady.”9 However, some visitors were beginning to suspect his true age, and so advertisements of the time made sure to declare things like “The General shed his first set of teeth several years since; and his enormous strength, his firm and manly gait, establish his age beyond all dispute.”10

In June, Barnum left the day-to-day management of Charles’s exhibitions to H. G. Sherman, and visited Paris to sightsee. When he returned, the “Tom Thumb Troupe” toured England as their contract with Egyptian Hall had expired. They took the miniature carriage along with them, and used it to great effect, setting it up outside each community and riding in to the amusement of surprised townspeople. But it was the full-sized carriage that almost led to Charles’s death. In August, while Charles and H. G. Sherman were sitting on the driver’s box, the horse ran down a steep hill, breaking its neck and smashing the carriage on a stone wall. A shaken Barnum emerged from inside the coach, expecting to see them dead. But Sherman had heroically grabbed Charles and leapt over the wall as the carriage crashed, landing in a soft green field without injury to either.11

In October Barnum suddenly left Europe, while H. G. Sherman continued to manage the troupe. He had already sent “Tom Thumb’s Court dress” back to New York to be put on display at the American Museum, along with one of Queen Victoria’s dresses.12 It did not quite have the same effect as being able to see “The General” in person, but it reminded everyone of last year’s triumph, and gave them hope that the little fellow would return. Still, the museum languished without its owner, and Fordyce Hitchcock was no doubt glad to have his boss back, however briefly. Barnum returned to England with his family after only three weeks and rejoined Charles in Scotland. The Scottish officials in Glasgow tried to levy a tax on Barnum and Charles, but were ignored. They followed the troupe to Dublin, Ireland, calling for £729 of income tax. Barnum wriggled out of it, despite making more money than he ever had in his life.13 On one day in Dublin 4,421 people attended his afternoon performances, and the combination of receipts and purchases totaled an equivalent of $1,343, a staggering sum at the time for one day’s work.14

The first signs of trouble between the showman and Charles’s parents had become evident by this time. Cynthia “began to be too inquisitive about the business & to say that she thought expences were too high.” Barnum told her that he was the manager, and that “unless the whole was left to my direction I would not stay a single day,” calling them “blockheads and brutes” to his friend Moses Kimball.15 This threat to quit worked, because the Strattons seemed to know they would be at sea without Barnum. Money was not the issue between them, since Charles’s salary had increased to $25 a week, and when that contract expired, it increased to $50 plus expenses.16 The Strattons were also making good money on the merchandising of souvenirs. Then, on January 1, 1845, they began to earn half the proceeds, making Sherwood and Cynthia some of the richest people in Bridgeport. One newspaper reported that, excluding Barnum’s profits, the Strattons’ takings equaled more than £150,000, at that time about a half-million dollars American.17 And though Charles was doing almost all the work, like all child stars, his parents and Barnum reaped the benefits. However, the conflict between the two controlling parties remained, and would escalate as their tour continued.

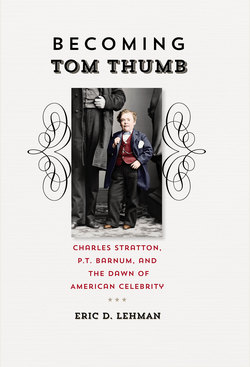

This oil painting by Ramsay Richard Reinagle from 1844 shows Charles exhibiting at London’s Egyptian Hall. Photo by Paul Mutino. Collection of The Barnum Museum, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

Barnum’s wife Charity and children Caroline and Helen joined them on the tour of Great Britain, and then followed the troupe to Paris on March 18, enjoying the metropolitan paradise it offered. They rented rooms at a hotel on the Rue de Rivoli and began performing at the three-thousand-seat Salle de Concert on the rue Vivienne. Paris of the mid-nineteenth century was just as incongruous a place as London, maybe more so, with what James Fenimore Cooper had described as “dirt and gilding … bedbugs and laces.” The aromas of coffee and baking bread wafted across the unswept streets every morning, and domes and spires of palaces and churches rose above noisy, labyrinthine streets lined with grime-walled houses. People of all classes strolled along the chestnut-lined avenues or through the Garden of the Tuileries, and sat on the terraces of cafes to sip wine together.18

There were few Americans in the city at this time, and since Benjamin Franklin had walked these streets in the 1770s and 1780s, none had drawn the often indifferent attention of the French so much as Charles Stratton. The daughters of the French king, Louis Philippe, had seen Charles perform in London, and “General Tom Pouce” was immediately invited to the Tuileries Palace. Louis Philippe was a progressive king who had to, as Victor Hugo put it in Les Miserables, “bear in his own person the contradiction of the Restoration and the Revolution, to have that disquieting side of the revolutionary which becomes reassuring in governing power … He had lived by his own labor. In Switzerland, this heir to the richest princely domains in France had sold an old horse in order to obtain bread.” He had also been to the United States, and was a huge fan of the American “go-ahead” mentality that Barnum and Charles represented to Europe.

The French court asked questions of the two Americans, and Louis Philippe reminisced about his exile there. “What can you say in French?” he asked Charles. “Vive le Roi,” Charles replied cheekily.19 The editor of Journal des Débats was also present and reported the next day: “General Tom Thumb accompanied by his guide, Mr. Barnum, has had the high honor of being received at the palace of the Tuileries, by their Majesties the King and Queen of the French, who condescendingly personally addressed the General several questions respecting his birth, parentage and career. … The King presented this courteous and fantastic little man with a splendid pin, set in brilliants, but it had the convenience of being out of proportion to his height and size. It might answer for his sword. …”

Charles danced for the king, and the Journal reported his “extraordinary lightness and nimbleness, even as a dwarf.” He had reached the point where he could improvise with dancing as well as humor, because “he executed an original dance, which was neither the polka, nor the mazurka, nor indeed anything known.” However, it was apparently not very well received, since the paper joked that “no one will ever venture to try it after him.”20

More significantly, an important part of Charles’s repertoire needed to be left at the border. The Journal des Débats warned, “We will not mention a celebrated uniform which he wore in London, and which was amazingly successful with our overseas neighbors. General Tom Thumb had too much good taste to take the costume to the Tuileries. We hope, then, as he possesses such fine feelings, that while he sojourns in Paris, he will leave it at the bottom of his portmanteau.”21 The Journal was of course referring to the Napoleon costume he wore for Queen Victoria and the Duke of Wellington.22 Despite this admonishment, Barnum claimed that Louis Philippe asked for the Bonaparte character “on the sly”—no doubt what would have been offensive to the populace was quite funny to this heir of the Bourbons.23

Barnum also asked the King for permission to take part in the Longchamps celebration. Once an annual religious ceremony, this was now a display of pomp and wealth on the glamorous Champs Elysses and in the green fields of the Bois de Boulogne. The king instructed the prefect of police to give Barnum a permit. The tiny carriage had been shipped across the Channel and took its place in the parades along the crowded boulevards. The French people cheered their new celebrity: “Vive Le General Tom Pouce!” Barnum had once again arranged free advertising, and the later exhibition was a huge success, with 500 francs taken on the first day. Two months of afternoon and evening performances were booked solid.24 Chocolates and plaster statuettes sold at every gas-lit shop, and the café Le Tom Pouce was named in his honor. The famous Goncourt Brothers refer to Charles in their journals, when making fun of a painting, comparing the subject to “Tom Thumb in Napoleon’s Wellington boots.”25 And Barnum made sure it was not just the wealthy that saw Charles. On Sundays he took him to the gardens on the outskirts of Paris where he performed for free.26

Along with fascinating new acts, in which he would be dragged in a large wooden shoe or served in a pie, he appeared in a farcical play, mostly as a walk-on, though he was described as “well-formed and graceful,” while passing between the legs of ballet dancers. He also continued his costumed poses; they loved his highland outfit in Paris, and he handled his tiny sword well. But the favorite of the French may have been the “character of the gentleman,” in which “he takes out his watch and tells you the hour or offers you a pinch of snuff or some pastiches, or a cigar, each of which are in uniformity with his size.” But, as the Journal des Débats pointed out, “He is still better when he sits in his golden chair, crossing his legs and looking at you with a knowing and almost mocking air. It is then that he is amusing; he is never more inimitable than when he imitates nothing—when he is himself.”27

This point of view would become the prevalent one in the following years, and although Charles would act in many plays over the next decade, he “posed” less and less often, and when exhibiting in public simply behaved as himself: a very funny human being. How else does someone become a comedian other than rehearsing the routines of others? After a time, there is no need for rehearsal, and comic timing and “quick wit” become natural.

At the same time as Charles was growing as a comedian, conflicts erupted around him. Along with condescending officials annoyed by the attention being paid to a “dwarf,” there were always people trying to surreptitiously cash in on his success. In May, Sherwood had to sue a man named Nestor Roqueplan, manager of the Théâtre des Variété, who was advertising a play called “Tom Pouce.” The Tribunal of Commerce awarded victory to the American plaintiff, since “the young Stratton was known by the name of Tom Pouce.” The manager had to remove the bills and pay all the costs of the suit.28 But the worst conflicts were between Charles’s parents and Barnum, and were becoming more acute the longer they toured together. Furthermore, the showman’s family had gone home to America by this time, and he was not in the best humor.

P. T. Barnum’s tutoring helped to bring out Charles’s natural comic talents at a young age. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY.

After showing in Paris for three and a half months, during which time Charles “hit them [the public] rather hard,” the troupe left to tour Belgium and rural France.29 The company had grown to twelve people, including assistant manager H. G. Sherman, a piano player and an interpreter, Professor Pinte, as well as the tiny carriage and ponies. So, Barnum bought three large diligences and twelve horses, saying “persons catering for the public amusement must dash ahead and damn-dang the expense … When the public sees twelve horses, twelve persons, and three post carriages come into town, they naturally begin to inquire what great personages have arrived.”30 The method worked, and the border crossing into Belgium made such a scene that a customs officer asked if Charles was a “prince.” Apparently H. G. Sherman exclaimed, “he is Prince Charles the First, of the dukedom of Bridgeport and the kingdom of Connecticut.” A few days later, the “Prince” appeared in Brussels at the palace of “fellow royalty” King Leopold and Queen Louise-Marie, though they had already seen him in London.31

While in Belgium, Barnum visited the battlefield at Waterloo, the event then less than three decades in the past. The immense conical hill of the Butte du Lion had already been raised to commemorate the famous battle, and various “humbugs” had turned the battleground into something like Barnum’s own museum, with a firm in England manufacturing relics and know-nothing tour guides lying to the visitors.32 The following day Sherwood and some of the troupe went to Waterloo as well, but their carriage broke down. Barnum took the opportunity to play a mean trick on the Bridgeport former carpenter, saying that the show had lost all the money that afternoon. He repeated the story in print, making Charles’s father look like a complete fool. He continued with a story about Sherwood falling asleep on a Belgian barber’s chair, unwittingly having his black, bushy hair shaved down to the scalp.33

Though Barnum’s complaints took the form of jokes, in lashing out at him in this public way, he clearly didn’t like Sherwood very much. Most of the jokes were at the expense of Sherwood and Cynthia’s provincialism, saying “Yes, the daddy & mammy of the Genl. Are the greatest curiosities living …” He joked that “The General’s father is perplexed to get along with the French (who he calls damn fools for not knowing how to speak English).”34 He also claimed Sherwood thought the Dutch were from Western New York, and was surprised to hear them in Belgium.35 Cynthia apparently loved the Toujours sausages she ate in Brussels, and Barnum took great pleasure in telling her they were filled with donkey meat.36 While saying that Charles was “merry, happy, & successful,” Barnum said bitterly, “Stratton is laying up $500 per week, & I guess Bridgeport will be quite too small to hold him on our return. And as for his wife, she will look upon N. York or Boston as dirty villages quite beneath her notice.”37 They came across as the worst sort of country bumpkins to everyone concerned, including the readers of the New York Atlas.

And Barnum did not confine his lampoons to print. He subtly tortured Sherwood, telling visitors to Charles’s exhibitions that the 5′8″ ticket-seller was the dwarf’s father, ensuring that he was hounded by questions from the audience. This was bad enough when the nosy Londoners crowded round him in their soot-black coats. At least he could speak their language. But in France or Belgium this was a horror for the unsophisticated and insular man.38 Later, Barnum actually read out the “letter” in which he had told the Waterloo story directly to Sherwood’s face, and said afterwards that “he did not like it, but he tried to laugh it off—he failed however.”39

This passive-aggressive behavior on the showman’s part is as unflattering as the incidents are for the Strattons. In all these cases, Sherwood is portrayed as greedy, angry, and frustrated, and Cynthia as stupid and vain. We can assume that they did not have a high opinion of Barnum either, and probably made their feelings known in front of Charles. Regardless, these quarrels were no doubt picked up consciously or unconsciously by the young performer. Like any young “Prince,” his relatives and courtiers fought for his influence, for his money, and for his love.

And the fights would only get worse.