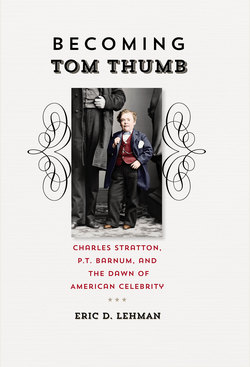

Читать книгу Becoming Tom Thumb - Eric D. Lehman - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE : PLAYING THE PALACE

Charles Stratton raced down the long, glittering halls. The two men with him walked steadily, even formally, but his tiny legs could barely keep up, even at a run. One man was his mentor and manager, Phineas Taylor Barnum, who towered over Charles by almost four feet, though he himself was not unusually tall. Both were common Connecticut Yankees, but if either felt nervous at being in Buckingham Palace they did not show it. This was one thing for a confident showman who knew well the humbugs hidden behind the glitter. But for a child who had stopped growing after a few months of life, and now stood only two feet high and weighed only fifteen pounds, it was a miracle.

The showman and the child had not been in England long. Arriving in Liverpool on the transatlantic steamer Yorkshire after a grueling nineteen-day journey from New York, accompanied by Charles’s parents and a tutor, they had subsequently given scattered exhibitions in Liverpool and London to limited success. After all, there were dozens of “dwarfs” exhibiting around the lush green countryside and blackened factory towns of England. But P. T. Barnum never shrank from a challenge, and tried a new approach, renting the former home of Lord Talbot at 13 Grafton Street, in London’s wealthy West End. From this prominent address he sent formal invitations to aristocrats, newspapers, and politicians to visit “General Tom Thumb, the celebrated American dwarf.” The ploy proved irresistible. A reporter from The Patriot visited him at Grafton Street, writing of Charles: “He is playful in his manner, acute in all his answers, very observant of all that passes or is said before him, and takes part in light conversation and even vouchsafes to be jocular.” They also noted that the boy was not sickly, seemingly surprised that “he possesses great strength for his stature.”1

One of the first aristocrats to take the bait and invite Charles and Barnum to her London home was the Baroness Charlotte de Rothschild. Her open carriage picked them up at Grafton Street and drove the pair to the imposing mansion at 148 Piccadilly, where servants ushered them upstairs to a drawing-room. The Baroness and twenty friends received them, and under the glare of candelabra, Charles danced a hornpipe that he had learned aboard ship, and sang in his unearthly treble voice. For their trouble, a “well-filled purse” was slipped into Barnum’s hand. Word got around, and more wealthy Londoners invited them to their homes.2

But it was the American ambassador, Edward Everett, who held the key to everlasting fame and riches. Barnum brought a letter of introduction to Everett, and he and Charles dined with the ambassador on March 2, 1844. Everett wrote that he had “General Tom Thumb to lunch with us to the great amusement of the whole family and household. A most curious little man. Should he live and his mind become improved, he will be a very wonderful personage.” A few days later, on March 8. Everett invited both “Tom Thumb” and the master of the Queen’s household, Mr. Charles Murray, to his home.3 Barnum knew this might be a scouting mission for Murray, and mentioned casually that he was thinking of taking “the General” to Paris to meet with Louis-Philippe, the French king. The stratagem clearly worked, because the next day they were invited to a “command performance” at Buckingham Palace, and as Murray told them, Queen Victoria wanted to make sure “that the General appear before her, as he would appear anywhere else, without training in the use of titles of royalty.” She “desired to see him act naturally and without restraint.” After spending the next two weeks using this royal request to gain entrance to more houses of the British peerage, on March 23 Barnum shrewdly put up an apologetic placard at the entrance to the Egyptian Hall where Charles had been performing. It read, “Closed the evening, General Tom Thumb being at Buckingham Palace by command of her Majesty.”4

Now, in Buckingham Palace, Murray led the two Americans through the gleaming corridors and up a marble staircase. Ahead, two dozen people gathered in a long, glass-roofed picture gallery, all in the finest clothing money could buy, and sparkling with diamonds. The exception was the twenty-four-year-old Queen Victoria, who Barnum described as “sensible and amiable,” but was surprised that “she wore a plain black dress … She was the last person whom a stranger would have pointed out in that circle as Queen of England.”5 Barnum may not have known, but the young monarch had put her court officially in mourning for Prince Albert’s father, the Duke of Saxe-Coburg, who had died on January 29. This entertainment may have been the first chance for the court to laugh in almost two months.

Charles himself had been attired in “court dress,” with a red velvet coat and breeches, white stockings, black buckled shoes, powdered wig, cocked hat, cane, and ceremonial sword. His blond hair framed a perfectly round face, with rosy cheeks and bright eyes, a perfect “man in miniature.” He “advanced with a firm step, and as he came within hailing distance made a very graceful bow, and exclaimed ‘Good evening, Ladies and Gentlemen!’” A titter of laughter ran around the room. The smiling Queen took his small hand and led him around the picture gallery, which he proclaimed “first-rate.” She asked him many questions and everyone chuckled at his lively answers. He gave a routine that included his recently practiced imitation of Napoleon.6 Victoria wrote about the encounter that night in her diary:

After dinner we saw the greatest curiosity I, or indeed anybody, ever saw, viz: a little dwarf, only 25 inches high & 15 lbs. in weight. No description can give an idea of this little creature, whose name was Charles Stratton, born they say in 32, which makes him 12 years old. He is American, & gave us his card, with Gen. Tom Thumb written on it. He made the funniest little bow, putting out his hand & saying: “much obliged Mam.” One cannot help feeling very sorry for the poor little thing & wishing he could be properly cared for, for the people who show him off tease him a good deal, I should think. He was made to imitate Napoleon & do all sorts of tricks, finally backing the whole way out of the gallery.7

As Charles retreated from the picture gallery in proper deference to royalty, he found he could not keep up with Barnum’s long legs. He backed, tripped, then turned and ran, then tried again, provoking laughter from the nobles and ferocious barks from the Queen’s tiny, flop-eared spaniel, which no doubt seemed the size of a wolf to him. Without a moment’s hesitation Charles attacked the spaniel with his tiny cane in a mock battle, creating what Barnum said was “one of the richest scenes I ever saw.” The courtiers nearly fell over themselves with glee, and the Queen sent an attendant to make sure the little man “had sustained no damage.” Joining the fun, Charles Murray added that “in the case of injury to so renowned a personage, he should fear a declaration of war by the United States.”8

Charles Stratton’s spontaneous mock battle with Queen Victoria’s spaniel became comedy legend. From Barnum’s Struggles and Triumphs, courtesy of the University of Bridgeport Archives.

Upon returning to Grafton Street, Barnum immediately wrote a grateful letter to Ambassador Everett:

Ten thousand thousand thanks for your kindness. General Tom Thumb and myself have just returned from a visit to Her Majesty the Queen, in compliance with the royal command delivered this afternoon by Mr. Murray. The Queen was delighted with the General, asked him many questions, presented him with her own hands confectionary &c, and was highly pleased with his answers, his songs, imitation of Napoleon, &c. &c. Prince Albert, the Duchess of Kent, and the Royal Household expressed themselves much pleased with the General, and on our departure the Queen desired the lord-in-waiting request that I would be careful and never allow the General to be fatigued.9

Everett himself told his American correspondents that “Tom Thumb” was “the principal topic of conversation here [in England],” writing further, “He is really a very curious specimen of humanity. It is to be hoped that his parents, who are with him, will spare his strength; and give him a good education out of the golden harvest he is reaping for them.”10

On a subsequent visit, on April 6, Queen Victoria received Charles and Barnum in the Yellow Drawing Room, with its “rich yellow satin damask” on the couches, sofas, and chairs, the chamber paneled in gold, with carved and gilt cornices. Charles told the queen he had seen her before. When the queen asked him how he was, he replied “Yes, ma’am, I am first rate.” He told her graciously that “I think this is a prettier room than the picture gallery. That chandelier is very fine.”11 Her husband Albert, the Prince Consort, their son Edward, the two-year-old Prince of Wales, and his sister three-year-old Princess Victoria were also present at this second meeting. The young Prince Edward had missed the first encounter, asleep in bed at the time, and though he was to meet Charles a number of times over the next few decades, he claimed to have never got over the disappointment of missing him on that initial visit.12

Victoria wrote in her diary again: “Saw the little dwarf in the Yellow Drawingroom, who was very nice, lively & funny, dancing and singing wonderfully. Vicky & Bertie [Edward] were with us, also Mama, Ldy. Dunmore and her 3 children, & Ldy Lyttleton. Little ‘Tom Thumb’ does not reach up to Vicky’s shoulder.”13 Introduced to the shy Prince of Wales, Charles said, “How are you, Prince?” Then after measuring himself against the two-year-old child, he continued, saying, “The Prince is taller than I am, but I feel as big as anybody.” He gave his performance again, making the sort of mistakes children often do that provoke laughter. He sang his signature song, a revised version of “Yankee Doodle,” without prompting, to the good humor and delight of the assembled British court.14 The following day, the London Times reported that:

Her Majesty graciously received General Tom Thumb, the celebrated American dwarf, accompanied by his guardian, Phineas T. Barnum, Esquire, to repeat the entertainment which so pleased the Queen, the Prince Consort, and the Duchess of Kent on March 23rd. After the performance, witnessed by Her Majesty, the Queen, His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales, the Princess Royal, the Queen of the Belgians, and a distinguished gathering, Queen Victoria was pleased to present to the General, with her own hand, a superb souvenir of gold and mother-of-pearl, set with precious stones. On one side were the crown and the royal initials, “V.R.,” and on the reverse a bouquet of flowers in rubies.15

On Charles’s third visit to the Palace, on April 19, King Leopold of Belgium and his wife Louise Marie were present, and were, according to Victoria “surprised” by the boy’s size and talent.16 On May 30 he had dinner again at Ambassador Everett’s house, walking on the dinner table in a feat that apparently never failed to amuse everyone.17 At Marlborough House he entertained the Dowager Queen Adelaide and the Duke of Devonshire. His wardrobe had expanded considerably by this time, and he wore an embroidered brown silk-velvet coat and short breeches, a white satin vest, white silk stockings and shoes, a wig, and his tiny ceremonial sword barely ten inches long. The Dowager Queen was so taken with him she offered him a watch and chain, accompanied by a severe lecture on morality.18 Then on June 8, the Russian Ambassador sent for Charles to be presented to his Imperial Majesty, Tsar Nicholas, who was visiting England, leading to “a strange encounter” of the “smallest and greatest personages in existence” and an invitation to St. Petersburg.19

But it was the encounter with the Duke of Wellington that became comedy legend. The Duke stopped by one of Charles’s exhibitions at Egyptian Hall, finding “General Tom Thumb” in his Napoleon costume, apparently deep in thought. The British hero of the Napoleonic Wars approached the miniature man dressed in the outfit of his enemy, and asked him what he was sad about. “I was thinking of the loss of the Battle of Waterloo,” Charles said morosely. Whether Barnum had known the Duke was coming and fed Charles that brilliant rejoinder, or whether the clever boy himself had come up with it, Wellington eagerly told the story of the two “generals” throughout London, and accounts of the dialogue spread quickly through the British press. As Barnum said, this event “was of itself worth thousands of pounds to the exhibition.”20 This incident and the humor inherent in such a great warrior being played by such a little person were enough to make the portrayal unforgettable. But of course, Napoleon’s reputed lack of height gave the impersonation a ring of truth that made it one of the jokes of the century.

Rehearsed or not, the wit of this tiny American was on display every day, and all went away satisfied with his charm and talent. From March 20 to July 20, 1844 “General Tom Thumb” packed Egyptian Hall, averaging a take of £500 a day doing his impressions of Napoleon and comedy routines with Barnum. He added a new lyric to his performance of “Yankee Doodle,” singing, “I’ve paid a visit to the Crown, Dressed Like any grandee: The Queen has made me presents rare, Court ladies did salute me; First rate I am, they all declare, And all my dresses suit me.” He became a figure of fun in the satirical magazine Punch a number of times, called “The Pet of the Palace.” He visited the homes of the rich and famous at night for £50 apiece. By this time he had “polkas and quadrilles named after him” and could not travel anywhere without his parents fearing he would be trampled underfoot.21

In another stroke of advertising genius, Barnum had a miniature coach crafted by a carriage-maker in Soho, colored ultramarine with crimson and white trimmings, and reportedly measuring only twelve inches wide. Ponies from Astley’s Royal Amphitheatre pulled it around the parks and avenues.22 Barnum wrote to his friend Moses Kimball about them: “His carriage, ponies & servants in livery will be ready in a fortnight and will kill the public dead. They can’t survive it! It will be the greatest hit in the universe, see if it ain’t!”23 The carriage and its gear cost over £300, but that sum was less than a day’s work for Charles and Barnum at this point. The coach featured a “coat of arms” that included the British lion and American eagle, as well as the Yankee motto “Go Ahead” painted on the side. Two small boys served as coachman and footman respectively.24 This was the final piece to the marketing puzzle, because as Barnum had hoped, the sight of Charles being driven around London in this tiny carriage sent the English people into an uncharacteristic frenzy. In a letter to a friend the following year, Barnum put it succinctly: “The fact is no man can live after seeing his little Equippage, without seeing the General himself, and after seeing him they must talk about him. The little rogue is a sure card wherever he goes.”25

Pictured here the year before she met Charles, the young Queen Victoria catapulted him to international stardom with her patronage. Courtesy of the University of Bridgeport Archives.

Victoria herself was still talking about her encounters with the American prodigy a year later, when Edward Everett visited her at Windsor Castle. Charles had “evidently amused her very much.”26 Told by Barnum that “Tom Thumb” was twelve years old, the Queen throughout these encounters treated him like a young man. But that fib about his age was another piece of public relations propaganda. When he became the darling celebrity of the English crown, Charles Stratton was barely six years old.