Читать книгу Sargent's Daughters - Erica E. Hirshler - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSargent’s Daughters

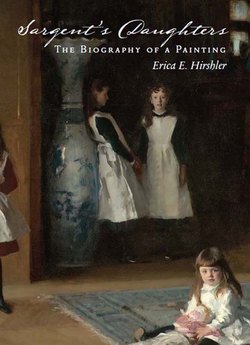

JOHN SINGER SARGENT never had daughters - or, in fact, any actual children. He left instead a legacy of a different kind, one of canvas and paint rather than flesh and blood. Today his sons and daughters hang in museums and galleries around the world; they seem as vividly alive as they did when they left the artist’s studio in the nineteenth century. But one painting of children stands out from all the rest: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, a large picture of four plainly dressed young girls in a vast and indistinct room (plate 1.1). They were the children of friends of Sargent’s, and their parents allowed him to create a portrait of them that is barely a likeness, a painting that skirts the very definition of the genre. It is a haunting scene, one that has captivated and puzzled viewers for more than a hundred years. These girls are truly Sargent’s daughters, his creation if not his progeny. Through them, Sargent’s place in history has been assured. As the artist himself commented, Boit portraits had always brought him luck.1

The pages that follow are a biography, but not just of Sargent, or Edward Boit, or his four daughters. It is all three of those things and more, a rich tale of painter and patron, friends and families, privacy and public display, fame and obscurity. It is a story about how the portrait came to be made and what happened after it was finished, both to the people involved and to the object itself, the great work of art that now hangs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. It is also an account of how viewers reacted to this unusual picture when it was first displayed and how perceptions of it have changed over time. This is the biography of a painting.

Sargent’s daughters were the children of Boston artist Edward Darley Boit and his wife Mary Louisa Cushing Boit, more familiarly known as Ned and Isa. Their girls were eight-year-old Mary Louisa, named for her mother and like her called Isa, standing demurely at the left in the painting (plate 1.2); four-year-old Julia (nicknamed Ya-Ya) sitting on the floor (plate 1.3); Florence (Florie), at fourteen the eldest, leaning against the vase in the background; and twelve-year-old Jane (Jeanie) hovering in the dim light beside her (plate 1.4). The Boits and Sargent met in Paris, where all of them had lived since the mid-1870s. With numerous friends (including novelist Henry James) and interests in common, Ned and Isa had many opportunities to cross paths with Sargent. They all loved art and music; they shared a passion for Italy, an appetite for travel, and the untethered experience of being Americans abroad. In the fall of 1882, they collaborated to produce a masterpiece on canvas.

Their relationship did not end there. Unlike many portrait commissions, which most often are simple business transactions that conclude when the painting is complete, Sargent’s relationship with the Boit family was long lasting and complex. He stayed with the Boits when he came to Boston in 1887, his first working trip to the United States. They kept in touch directly, in person and by post, and also indirectly, as their news was shared in the letters of their friends, including Henry James. The Boits and Sargent socialized with one another in London, after Sargent had established his studio practice there. And more than twenty-five years after the portrait was made, Sargent and Ned Boit collaborated on two joint exhibitions, watercolor displays that would demonstrate their relative strengths as painters and foretell each man’s lasting reputation.

Today John Sargent is heralded as one of the nineteenth century’s most brilliant artists, while Ned Boit has largely been forgotten. Isa Boit, the girls’ mother, is often entirely unmentioned, even though her ebullient personality is clearly evident in Sargent’s 1887 portrait of her. Few people are familiar with what happened to the girls, although some know that none of them ever married, and others have heard that they were crazy; the two ideas are sometimes inextricably linked in people’s imaginations. The oversized Japanese vases that now flank the painting in the MFA’s galleries are the only extant remnants of the Boits’ plush lifestyle, which was full of people and possessions, trunks, harps, and canaries. The scalloped rims of the vases are damaged, a testament to the activities of their owners, who moved continuously within the glittering cocoon of expatriate life in Europe and who traveled back and forth across the Atlantic by steamship as regularly and easily as if they were frequent fliers boarding an airplane.

The Boits’ lives have been partially reconstructed here, based on a wealth of documentation that remains, alas, frustratingly incomplete. Ned Boit’s parents carefully saved the long and descriptive letters he wrote to them during his first trip to Europe in 1866-67. Ned himself kept a diary, briefly noting in it his daily activities, but the only volumes known to survive begin in 1885, three years after the portrait was painted. His younger brother Robert, called Bob, was the responsible businessman who stayed home and looked after most of the family’s affairs. Bob was also the family historian, publishing a genealogical account of the Boit family and making lengthy, eloquent journal entries in a series of large ledger books that he later bequeathed to the Massachusetts Historical Society. Sealed from public view until fifty years after his death, Bob’s diaries now add vivid details to the story, albeit frequently from a transatlantic distance. Henry James’s voluminous correspondence includes mentions of the Boits and their children beginning in 1873, his insights often related in letters to their mutual friend Henrietta (Etta) Reubell, unpublished pages now in the collection of Houghton Library at Harvard University. James’s correspondence with Sargent does not survive, and Sargent, unfortunately, seems to have “binned everything as he went along,” in the words of his great-nephew and biographer Richard Ormond.2 Scattered letters from the painter concerning the Boits survive, some of them saved by Bob Boit, who carefully pasted them into his diaries.

And what of the Boit daughters themselves? Did they, like so many other women of their generation, write expansive letters and keep diaries? If they did, they have never been found, and perhaps they never will. “My sisters and I,” confessed Julia Boit in 1960, “had to destroy all old letters + papers when we left Italy after my father’s death - We were selling our property when World War One took place ... we had great difficulty.” She added that their destruction was “a pity ... but when we had to leave our house in Italy we had to leave in a hurry as we were only allowed there for a fortnight owing to the war.”3 The few known photographs of Julia and her sisters have turned up serendipitously in the albums of other family members; there are a handful of letters here and there, but they are only scraps from a richly appointed table.

One important document remains - the painting itself, with its memorable likeness of four young girls dressed in white. In it, the children look as if they were playing some mysterious game. The littlest one, silent and observant, sits in the foreground with her doll. She looks charming, with her straight-cropped bangs, round face, and inward-pointing toes. To the left and further back stands another, slightly older, pretty, and very still. With her arms clasped behind her back and one foot slightly in front of the other, she seems about to rise on her toes, a little ballerina. The two older children are in the back, in shadow, and harder to see. One mirrors the position of the girl at left, although her hands have fallen to her sides. Her face is the liveliest: her mouth is slightly open, as if she had just been speaking or moving about. The fourth leans back, the curve of her spine aligned with the shape of the large vase behind her. It seems as if we could walk right into their world, passing straight through to their enchanted dark space, where impossibly huge vases glimmer in the half-light. But when we get close to the girls, they vanish, dissolving into a jumble of paint, great slashing strokes of whites, pinks, greens, blacks, and browns, just as the history of their lives is fractured by incomplete documentation, stray whispers, and silence.

The painting itself continues to speak. Watching people look at it in the museum’s galleries can be fascinating. Viewers seem to spend more time with it than they do with others in the room where it hangs. Often they are artists, bewitched by Sargent’s ability with the brush. Sometimes they are mothers who use the picture’s accessibility - the youngest girl sits so close to the visitor - to engage their own small children. Some visitors beg the museum staff for admission to the gallery if the room is closed for an installation, usually recounting the long distances they have traveled just to see this one thing, this icon, this masterpiece. People weep in front of it. James Elkins, in his book Pictures and Tears, a meditation on the emotional responses art can generate, wrote of a man who shared with him the fact that whenever he and his wife visited the MFA, “she goes to see John Singer Sargent’s Daughters of Edward D. Boit. She stands there, crying, for about twenty minutes. He says she has never offered him any explanation ... there may be a quality in the painting that disturbs memories this woman cannot quite recover.”4 Elkins assumes her recollections are unhappy, based on some ineffable discontent she sees reflected in the portrait - but they could equally be based on wistfulness, or loss, or even sentimental desire.

Reactions to the painting are often intensely personal and seem solidly rooted in the viewer’s own relationships. Art historians are taught and reminded that it is impossible to be impartial, that every analysis is colored by the experiences of an individual observer at a specific time. Even so, The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit has elicited more interpretation than most portraits of children. Many have been tempted to see the Boit daughters enacting a narrative of the stages of childhood, from toddler to adolescent. This vision has caused other ghosts to appear alongside the girls, most notably those of twentieth-century psychologists like G. Stanley Hall and Sigmund Freud. With their theories in mind, some viewers look at Sargent’s portrait through a veil of psychoanalysis, watching the girls turning inward as they age, transformed from the uninhibited (open, light) life of childhood to a more restricted (closed, dark) world of adolescence and adulthood. In consequence and over time, the painting has been interpreted in many different ways. Soon after it was finished, James described it as a “happy play-world of a family of charming children.” The author later demonstrated in his novel The Turn of the Screw (1898) that he knew something about children and evil, but he saw nothing unusual in Sargent’s depiction. In contrast, an anonymous blogger in 2005 found the image distinctly unpleasant, proposing that the “availability” of the youngest child, sitting in the light with her doll between her legs, meant something quite different from innocent play.5

How could such a transformation from purity to corruption take place? Or is that later interpretation entirely off the mark, revealing more about the observer than the observed? Is the painting a simple portrait, a complicated artistic problem, an emotional treatise, or some intoxicating combination? Who was John Sargent in 1882, and what did he see and/or seek that year when he painted these girls? What role did the Boits play in its artistic conception? Does the fact that none of the girls later married have any relevance to our understanding of a painting made when they were children? How and when did their portrait come to represent to so many viewers an illustration of defined psychological traits?

The goal of this book is to explore, insofar as it is possible, all of those questions: to investigate and bring to life the story of the artist, his patrons, and his sitters, and to relate what happened to all of them after the portrait was made. The painting - a physical object - also has a narrative, enacted both before and after its dramatis personæ had passed from the world. These stories can be told without destroying any of the special magic this canvas weaves, for one of the powers a masterpiece exerts is its ability to speak to many people in countless ways over a long period of time. Sargent’s viewers, both past and present, have interacted with The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit on a variety of levels. There is no right or wrong response, no single way to react, no one path to falling in love. From this singular picture, a novel unfolds.