Читать книгу Sargent's Daughters - Erica E. Hirshler - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

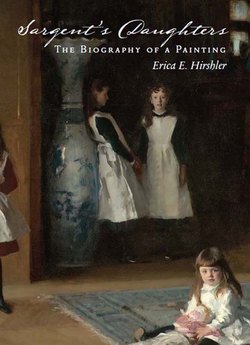

ОглавлениеThe Boits, Sargent, and Children

BY THE TIME Sargent’s work on their daughters’ portrait began, Ned and Isa Boit must have known the artist quite well. Unless Sargent had been thinking about it for some time (and no evidence suggests that he did), the painting sprang into being very quickly. It is equally a portrait and an interior, an homage to modern painting and to the art of the past, and one of Sargent’s greatest works. The exact circumstances surrounding its genesis are unknown; nothing chronicles a formal agreement between painter and patron. Sargent clearly was given considerable artistic freedom with the composition. His portrait was entirely unorthodox, for it is very unusual in a commissioned likeness to obscure the features of two of the sitters. It was made for people who understood both Sargent’s aesthetic sensibility and his artistic ambitions, individuals who had more of a connection to him than clients undertaking a business transaction. The relationship between Sargent and the Boits provides one clue to the painting’s unconventionality.

Ned and Isa had probably first met Sargent in France in the late 1870s. Their social and artistic circles intersected broadly, but it could have been Ned’s teacher François-Louis Français who provided the network that first drew them together. One of Français’s close friends was Carolus-Duran, Sargent’s instructor. Français and Carolus had met when they were both young art students in Paris in the late 1850s; they traveled together in Italy in 1864 and remained good friends for the rest of their lives.47 It seems likely that the path between their two American students, both of whom had Boston connections, would have been a short one. Sargent may also have met the Boits through mutual American friends, among them the Paris-based hostess Etta Reubell, either in the city or in one of a number of summer places, including St. Enogat and St. Malo, where all of them circulated in the 1870s. “Sargent was a great friend of us all,” Julia later explained.48

Before starting the portrait, and since the time he had completed ElJaleo and the Lady with the Rose (Charlotte Louise Burckhardt), Sargent had undertaken two other artistic campaigns that would affect his conception for his large and unusual painting of the Boits. One was a series of Venetian interiors that he created in 1880 and 1882, and the other was a small portrait of Louise Escudier, the wife of a prominent Parisian lawyer. Both had offered Sargent the opportunity to experiment with the placement of figures within a large interior space and to play with the effects of filtered and reflecting light. Many scholars have even suggested that The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, although painted in Paris, was the culmination of Sargent’s Venetian experience.49

The artist made two working trips to Venice in the early 1880s, the first during the fall and winter of 1880-81 and the second during the summer of 1882, after displaying El Jaleo at the Salon and just before starting the Boit portrait. His activities in Venice and the exact chronology of the works he made there remain somewhat obscure, but it is likely that he went with the intention of finding a subject he could work up into a Salon picture, as he had done on many other occasions.50 His 1877 trip to Brittany, for example, resulted in his important oil En route pour la pêche, which he displayed at the 1878 Salon. In the summer of 1878, Sargent went to Capri, a journey that inspired his next Salon picture, Dans les oliviers, à Capri (1879, private collection); in 1879, he went to Spain and Morocco, later producing the exotic North African-inspired Fumée d’ambre gris (1880, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute) and El Jaleo, shown at the Salon in 1880 and 1882, respectively. There is every reason to believe that Sargent had in mind to paint a Venetian subject for the Salon.

In September 1880, Sargent refused an invitation from Matilda Paget (the mother of his friend Violet Paget, better known as Vernon Lee), explaining to her that “there may be only a few more weeks of pleasant season here [in Venice] and I must make the most of them ... I must do something for the Salon and have determined to stay as late as possible.” In the summer of 1882, he again wrote to Mrs. Paget from Venice, apologizing that he was unable to visit her in Siena because he was “really bound to stay another month or better two in this place so as not to return to Paris with empty hands.”51 Sargent did not return to Paris entirely empty-handed, but neither did he ever display a major Venetian painting at the Salon. For that traditional venue, he would have needed to paint a large canvas, something worked up in the studio from the smaller paintings and drawings he had completed on-site. The sultry street scenes and shadowy interiors he had finished in Venice were too small, sketchy, and informal for the Salon, although he did show them at other more liberal and forward-thinking venues in both Paris and London.

Sargent’s Venetian paintings were unusual in their concentration on the city’s narrow back streets and its decrepit palaces - shabby interiors that betray few hints of their former richness - and in their deliberate avoidance of familiar tourist vistas. Martin Brimmer, a Boston art patron and one of the founders of the Museum of Fine Arts, called them “half finished ... inspired by the desire of finding what no one else has sought here - unpicturesque subjects, absence of color, absence of sunlight.”52 In part, Sargent’s refusal to record conventional scenes must have come from his search for an unusual subject to build into a Salon painting, one that would capture attention in the way that El Jaleo had done. If The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit can be read as the culmination of his Venetian studies, then the interiors he made there disclose some of the artistic problems he hoped to resolve.

Sargent completed about eight paintings in Venice that show interiors with multiple figures. Most of them depict large open rooms, the upper floors of canal-side palaces that by the 1880s served a variety of purposes, from artists’ studios to literary retreats to working-class apartments. Sargent used the long shadowy spaces as stage sets, moving his models around in intricately choreographed groupings. The figures do not always relate to one another, nor do they necessarily engage the viewer. In all of them, light filters through the area indirectly and often from the back, reflecting the polished pavement of the floor, glinting from furnishings and picture frames, and bathing the scene in a pearly opalescence that disguises as much as it reveals. The rooms and the activities that take place within them remain obscure and enigmatic, and Sargent deliberately avoids a clear narrative.

These Venetian interiors call to mind some of the more modern paintings Sargent might have seen in Paris, particularly the work of Edgar Degas. Sargent’s personal relationship with Degas, if any, is unclear. No known evidence documents more than a passing acquaintance between the two men, although Sargent’s name and his rue Notre Dame des Champs address do appear in one of Degas’s notebooks. Degas used the book for sketches and reminders during the period 1877-83, at just the moment when Sargent seems to have been most affected by the French master’s work. Both men were friendly with composer Emmanuel Chabrier and bassoonist Desiré Dihau, the main figures in Degas’s Orchestra of the Opéra (about 1870, Musée d’Orsay); Dihau also sometimes played with the Pasdeloup Orchestra, which Sargent depicted in 1879. Contemporary sketchbooks of both artists include lively drawings of the gaily dressed clowns who entertained between acts at the Cirque d’Hiver, where Pasdeloup performed, and also at the Cirque Fernando, where Degas painted. Sargent was well acquainted with a number of other artists and writers in Paris who could have brought him into contact with Degas - among them Jacques-Emile Blanche, Mary Cassatt, George Moore, Claude Monet, Auguste Rodin, and of course Carolus-Duran (although Degas disparaged him for his slick style) - but there is no record that any of them ever did. While Degas reportedly dismissed Sargent as “a facile painter but not an artist,” Sargent admired Degas: when he visited the third Impressionist exhibition in 1877, he made a pencil sketch after Degas’s pastel of a ballerina, L’Etoile, one of the few copies Sargent made after a contemporary work (Worcester Art Museum).53

Whether or not the two men knew or liked each other, the French master’s art became part of Sargent’s visual vocabulary. Echoes of Degas’s subjects and compositions reverberate in his paintings of the late 1870s and early 1880s. Sargent’s interest in subjects from modern life - the Luxembourg Gardens, the Pasdeloup Orchestra - reveal his awareness of the themes explored by Degas and his colleagues, among them the Italian painters active in Paris, such as Giuseppe de Nittis and Giovanni Boldini. The almost monochromatic palette and swirling design of Rehearsal of the Pasdeloup Orchestra at the Cirque d’Hiver (1879, private collection on loan to the Art Institute of Chicago) betray Sargent’s fascination with some of the unconventional formal qualities of Degas’s work. Sargent would never fully develop these avant-garde tendencies, preferring instead to maintain a more conservative profile; as Mary Cassatt snidely remarked, he cared too much what other people thought.54 But in his less formal paintings, including his Venetian interiors, he toyed with some of Degas’s motifs - the tipped-up floors, the oblique sources of filtered light, and the arbitrary arrangement of figures.

Sargent incorporated some of these ingredients into the portraits he was making during the same period. He posed Louise Escudier, for example, next to the tall windows of a Parisian interior, depicting her as a figure within a room rather than as a sitter standing before a backdrop (Madam Paul Escudier [Louise Lefevre], 1882, Art Institute of Chicago). This conceit allowed him to experiment with the effects of half-lights and shadows as they fell across her features from the side. Madame Escudier and the windows are reflected in the small mirror hanging in the background, further expanding the space and diffusing the silvery light. While the portrait is reminiscent of the fashionable French interiors with female figures painted by Sargent’s friend Alfred Stevens, a Belgian artist active in Paris, Sargent did not aspire to Stevens’s polish or to his fascination with the details of decoration and the luster of fabric. His canvas is roughly worked, with some areas barely sketched in and others thickly brushed. The painting relates equally well to his own Venetian interiors, particularly his studies of single figures, some small and some large, which seem to be the remnants of his abandoned ideas for a Salon picture.55

These same properties are apparent in Sargent’s portrait of the Boit daughters. Madame Paul Escudier may even have served as a sort of rehearsal for the Boits, giving Sargent an occasion to experiment with the placement of a figure within a domestic interior, a composition that combines elements of portraiture with an intensive study of light and shadow. The uneven paint surface of Madame Paul Escudier provides evidence of the numerous slight changes Sargent made to the locations of various objects in the room and suggests that he was working out those relationships as he went along. There are no such signs in the Boit portrait; the only areas showing pentimenti are Julia’s lap, where the position of the doll was changed, and the minor repositioning of the figure of Mary Louisa, which moved a bit further down in the picture. The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit (like El Jaleo) was painted directly and quickly, brush and palette knife employed with supreme assurance, all of its artistic problems solved in advance.56

Sargent had gained experience with painting children before he rendered the Boit girls; in fact, of all the early portraits he made that might be counted as commissions, fully one-third of them depict young sitters.57 Like any artist at the beginning of his career, he would have been glad to receive genuine orders for portraits, and in response he created engaging likenesses that often reveal the lively personalities of his subjects. Robert de Cévrieux, for example, posed for Sargent with his pet dog. Standing on an oriental rug before a curtained backdrop, the little boy, not yet breeched, is dressed in a fashionable skirted suit with a red bow. He appears to be a polite and dutiful child; his hair is brushed and shiny, his red socks are taut and even, and he presents a shy half smile to the viewer. The child’s restrained energy is made clear through his attribute, the small dog he squeezes tightly under his arm. The animal is alert and animated, squirming to be released, longing to enjoy a freedom that his owner would perhaps also prefer. Sargent borrowed the basic compositional format of Robert de Cévrieux from his teacher Carolus-Duran, who had exhibited portraits of his own children with their dogs at the Salons of 1874 and 1875. But the dashing facility with paint and the sense of contained action and movement were Sargent’s alone.

Sargent does not seem to have exhibited his portrait of Robert de Cévrieux in public, but he never regarded his images of young sitters as minor works, as some artists did. Two years later, in 1881, one of the two paintings that he selected to display at the prestigious Salon was a double portrait of children, then titled Portrait de M. E. P. et de Mlle L. P. (now called Portrait of Edouard and Marie-Louise Pailleron, 1881, Des Moines Art Center). It depicted sixteen-year-old Edouard Pailleron and his young sister Marie-Louise, the children of Marie and Edouard Pailleron, a prominent Parisian couple whom Sargent had painted (in separate portraits) in 1879. Sargent had shown his striking image of Madame Pailleron, dressed in black and crossing a spring green lawn, at the Salon of 1880. The following year, he returned to the exhibition with this likeness of her children seated together on a low divan strewn with oriental carpets. Although it incorporated similar props, this painting was a more complicated composition than Robert de Cévrieux. It proved to be a critical success for Sargent and served as an important precursor for his portrait of the Boits.

The story of the Pailleron commission enhances our understanding of the difficulties faced by any portrait painter, but it also reveals the particular vicissitudes of dealing with young sitters, who were often bored and sometimes uncooperative. Sargent posed the two Pailleron children in the controlled environment of his studio on the rue Notre Dame des Champs. However, the ability to manage the props and lighting did not mean that Sargent had power over his human subjects. In her later years, Marie-Louise wrote that her sittings had been interminable and fraught with tension. For any child, posing for long intervals of time would have been a trial. To gather more than one child together - two Paillerons or four Boits - and expect them each to behave in accordance with one another, to follow the painter’s wishes, and to keep still, was not an easy task.

The battle lines between the artist and Marie-Louise Pailleron had perhaps been drawn a year or two before. During the summer of 1879, when Sargent was with the family at their country home in Savoy, he often played with the children. It was a season not only of painting but also of butterfly hunting, and Marie-Louise later recalled Sargent searching out desirable specimens for his collection. After capturing the colorful insects, he acted “like an assassin,” she wrote, “asphyxiating his victims” under a glass with the smoke of his cigar. That Marie-Louise summoned up the event with such fascination and horror almost seventy years after the fact might demonstrate the lingering effect it had upon her, and it may explain some of her reluctance as a model, pinned, as it were, to the canvas. Frequent appointments with a young girl who had been characterized by her own grandmother as “spoiled too much by her father and ... too forward” cannot have been easy, nor were the two siblings the best of friends. Marie-Louise defined her sittings for Sargent as “a veritable state of war” and herself as a “rebel” who posed badly, fidgeted and chattered constantly, and refused to obey the painter’s requests. Her arguments with Sargent, which began with the details of her costume and her hairstyle and escalated over his desire to have her sit for extended periods, continued for some time. She was only convinced to settle down to pose by a visit from the dashing painter Carolus-Duran, who appeared in his protégé’s studio, explained that her father would be unhappy if Marie-Louise’s portrait was not a success, and disappeared again “like Jupiter in his storm cloud.”58

Uncooperative as she was, Marie-Louise’s descriptions of her sittings offer one of the few early records of Sargent’s studio on the rue Notre Dame des Champs and of his portrait practice in the early 1880s. The artist had, she said, “a large studio, very bright, but very untidy, in which the principal attraction, aside from the studies that hung on the wall, drifted over the furniture and even onto the floor (I remember a head of a Capri girl, a marvelous profile ...), was for me a grubby harmonium, whose keyboard I undertook to clean on my arrival.” As if she were trying to distance herself from her own misbehavior, Marie-Louise’s account shifts between the first and third person as she relates her own recalcitrance and the difficulties Sargent faced when trying to paint her. She was well aware of the tension in the studio and Sargent’s attempts to relieve it:

Of course ... my painter was unable to get his model to resume her pose, thence ensued a lively chase, leaping over obstacles, etc. From this harmonium, gray with dust, J. S. Sargent could, when he so desired, produce agreeable sounds; he was a good musician, and he also sang and played the guitar; when he was happy with his work he sang minstrel songs that amused me a great deal. To sing, he perched himself on the harmonium or on one of the ladders, long legs dangling - but that only happened in peaceful moments, and generally war reigned on the rue Notre Dame des Champs.

Vacillating between admitting her guilt and justifying her discomfort, she talked about the portrait: