Читать книгу Sargent's Daughters - Erica E. Hirshler - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеParis

IN FRANCE, the Boits joined an international community. Expatriates from the United States, South America, and throughout Europe found professional and social opportunities in Paris more attractive than anywhere else in the world. This stylish and sophisticated city had become a magnet for artists lured by its many opportunities for training and display; for intellectuals excited by its urbane and often witty exchange of ideas; for physicians and scientists seeking the latest experimental developments in their field; for statesmen engaged in diplomacy, at this time always conducted in French; and for entrepreneurs eager to provide shoppers at home with the latest luxury goods. People came from around the world to settle in Paris, but the most numerous, and the wealthiest, expatriate residents of the city were Americans. Some of them had discovered that an address in the most cosmopolitan of capitals was advantageous for business; others were drawn to its position at the center of the world of art, society, fashion, and entertainment; many discovered that their money bought more there than it did in the United States. Paris was also one of the world’s most modern cities; since midcentury, the French government had created a new metropolis of broad avenues and luxurious apartments punctuated by historic sites, relentlessly demolishing parts of the old capital, with its maze of twisting dark streets. The disruptions and unrest of the early 1870s had quickly been overcome; by the time the Boits settled in Paris, the city had easily re-established itself as the acknowledged center of shopping, dining, and artistic pursuits of all kinds. This elixir, with its mix of nationalities and entertainments, was addictive. As American portraitist Cecilia Beaux reported of one Mrs. Green, who lived in the Americans’ favorite quarter near the Etoile, “I never knew why [she] chose to spend her life in Paris ... perhaps, though she was a Shaw of Boston, and a ‘loyal subject,’ she found that, having once tasted, she could not do without the ‘milk of Paradise’ which many feel is to be found where she elected to remain.”32

When Bob Boit visited his brother and sister-in-law in Paris, he tasted that milk of paradise, keeping a diary of his daily activities. No doubt some special efforts were made to introduce him to the city’s many diversions, but the events the brothers experienced together that summer were not so different from the family’s regular routine and thus reveal many of the things the Boits enjoyed about life in Paris. One day, the brothers went shopping and took a drive through the Latin Quarter, stopping at the Luxembourg Gardens for a stroll before a late lunch at the fashionable Café de la Paix, on the boulevard des Capucines. The rest of the afternoon was spent at home and the evening at the new Opéra, where they heard the famed American soprano Emma Eames, a friend of Ned and Isa’s, sing her celebrated leading role in Charles Gounod’s Roméo et Juliette. After the performance, they returned to the Café de la Paix for a beer, taking pleasure in watching the bustle of the passing crowd. The next day, they went shopping again and then to the Louvre, where Bob Boit was particularly impressed with the paintings of Van Dyck, Rubens, Rembrandt, Velázquez, and Titian. Lunch followed at the Café d’Orleans in the Palais Royale, and then the brothers played billiards before returning home. In the evening, they dined at the renowned Café Anglais on the boulevard des Italiens and went to the theater at the Comédie Français.33

Among the many pleasures the Boits savored in Paris was the food, which Bob, like so many visitors, enumerated in rapturous detail. Of one meal at the famous Maison Dorée, a restaurant popular with a bourgeois and artistic clientele (and the location of the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition in 1886), Bob exclaimed, “Who would have supposed that the simple, vulgar turnip contained hidden from all but these blessed Frenchmen such a delicate aromatic flavor! What is the telegraph to such a discovery as that! ... thine be the palm, Oh, paper-capped chef, for taking a miserable common thing that has been served to swine for thousands of years + extracting there[from] a god-like essence to be treated with respect for ever + never to be forgotten. Place the turnip on top of the heap!” By the end of his visit, sated with food, wine, music, and art, Bob had converted completely to Ned’s point of view, becoming a champion of the beauties and pleasures of Paris. “So ends [my] journal of Paris,” he concluded. “It is the best city that I have come to yet in the World, + with a moderate fortune I should like to pass my life here ... I should be willing to be forced to pass the rest of my life there. I believe it the city of the world best suited to a man of artistic disposition + seems to me to contain all that is necessary for man’s happiness.”34 At last he understood his brother’s firm commitment to expatriate life.

While the Boit men clearly relished the many public pleasures of their surroundings, the women and children of the family would have inhabited a somewhat more circumscribed world. But women found happiness in Paris as well, and their entertainments consisted of much more than fittings at the couture salons of Worth or Doucet and shopping at the city’s many new luxurious department stores. Isa Boit was sociable and lively, and she delighted in what her friend James characterized as “the great Parisian hubbub,” which seemed to him, then at home in Boston, a “carnival of dissipation.”35 Like her husband, Isa enjoyed the opera, music, and theater, and she participated enthusiastically in the rounds of afternoon calls, teas, receptions, and dinners required of a woman of her class. She went riding and driving in the Bois de Boulogne and also entertained at home, putting the many elegant rooms in her apartment to good use.

The writer Edith Wharton reminded herself of an exceptional evening there in the 1880s when she met, for the first time, Henry James: “The encounter took place at the house of Edward Boit, the brilliant water-colour painter whose talent Sargent so much admired. Boit and his wife, both Bostonians, and old friends of my husband’s, had lived for many years in Paris, and it was there that one day they asked us to dine with Henry James. I could hardly believe that such a privilege could befall me, and I could think of only one way of deserving it - to put on my newest Doucet dress, and try to look my prettiest!” But the evening did not turn out as Wharton had hoped; her rose-pink dress failed to give her the assurance she needed. “Alas,” she said, the gown “neither gave me the courage to speak, nor attracted the attention of the great man. The evening was a failure, and I went home humbled and discouraged.” It was only later in her life, when she “had found” herself and “was no longer afraid to talk,” that she became one of James’s close friends, but she always remembered the sparkling evening of conversation that had tantalized her at the Boits.36

Although Wharton found herself mute in James’s company, Isa Boit did not. She adored him, as he did her; James thought of her as “always social, always irresponsible, always expansive, always amused and amusing.” Fond of people and of fun, she flourished in a continual round of engagements. Bob Boit assessed her as “strong, fascinating, full of grace, + with an extraordinarily penetrating mind - full of likes + dislikes - but never in any way or at any time small or spiteful - great-hearted - generous, exacting, loving, coquettish, humorous + with quick keen insight + appreciation of the thoughts and motives of others. She delighted in everything but the commonplace.” 37 She must have hoped that her four daughters would grow up to enjoy society as much as she did.

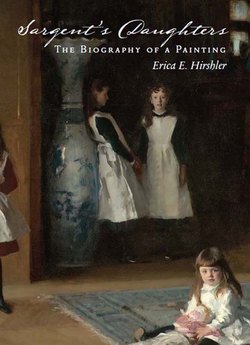

At the time Sargent painted them, the girls were still young and would not yet have participated in all of the activities of their parents, although they would have played in the park, gone for drives, and attended daytime concerts. Like Edith Wharton’s childhood, the Boits’ “little-girl life” was probably “safe, guarded, [and] monotonous.” 38 Their world was more clearly centered on the apartment, where they had a nursemaid and received their education from a private tutor. To reconstruct the lives of the Boit girls before they were immortalized in Sargent’s portrait, one must cobble together the sparse factual information with descriptions by other women of their age and social class who chronicled their own experiences growing up.

The earliest chapters in the Boit daughters’ lives presumably matched those of many other upper-class girls of their time. Wharton, for example, who was just six years older than Florie, remembered her “tall splendid father who was always so kind, and whose strong arms lifted one so high, and held one so safely,” as well as her “mother, who wore such beautiful flounced dresses, and had painted and carved fans in sandalwood boxes.” Mother and father were background figures for her, however, for she had “one rich all-permeating presence”: her nurse, Doyley, who was “as established as the sky and as warm as the sun.” Wharton, like the Boit girls, had been taken to Europe at a young age, but she realized that “the transition woke no surprise, for almost everything that constituted my world was still about me: my handsome father, my beautifully dressed mother, and the warmth and sunshine that were Doyley.” This semblance of stability was important for children like the Boits, and it was something that many families who were frequently on the move had in common. It created security within the family unit; as William James remarked of his brother Henry, “He’s really, I won’t say a Yankee, but a native of the James family, and has no other country.”39 This sense of place, of belonging to the family instead of (or in addition to) the state, served as the glue that kept families together despite constant travel. It also provided common ground for many expatriates, perhaps encouraging friendships among people who shared similar experiences, like the Boits, James, and Sargent.

Outside their home, the Boit girls probably enjoyed the city’s parks, where they would have been taken by their nurses to “[dodge] in and out among old stone benches, racing, rolling hoops, whirling through skipping ropes, or pausing out of breath to watch the toy procession of stately barouches and glossy saddle horses which ... carried the flower of [society] ... round and round.” Wharton’s parents went on from Rome to Paris, and she reminisced that they “were always trying to establish relations for me with ‘nice’ children, and I was willing enough to play in the Champs Elysées with such specimens as were produced or (more reluctantly) to meet them at little parties or dancing classes; but I did not want them to intrude upon my privacy.” She also recalled indoor activities, mainly kept separate from the adults but “led in with the dessert, my red hair rolled into sausages, and the sleeves of my best frock looped up with pink coral” to greet the guests at Sunday dinner, providing her with a glimpse into a grown-up world that was equal to the one Florie Boit received each time her parents asked her to entertain their own guests with her violin. Wharton, already demonstrating her own preferences, most often chose to read and to make up stories, apparently feeling no remorse or resentment about her insulated life.40 Like her, the Boit girls read, both together and alone, probably becoming familiar with the ever-growing selection of novels and articles written specifically for children. Their lives followed an established pattern, well protected from adult concerns and cares.

There is no indication that the young Boit girls sought any independence from this routine, and the impression given by the sparse notes in most of the existing adult diaries and letters is that they were rather passive. Yet a charming illustrated letter from ten-year-old Julia to her eleven-year-old cousin Mary, Bob’s daughter, confirms that their lives were not confined to the house and were also full of activities and fun:

I have still got my doll but its head broke and it has got a new head, with brown hair. I have been to lots of places this spring, twice to the grand Opéra to see “Romeo and Juliet,” to the Hippodrome, and to the Chatelet to see “Le Tour du Monde en 80 jours.” And I have also been to the Circus and to the Exhibition [the 1889 world’s fair]. There’re lots of funny things at the exhibition . . . I think you would like it very much. Have you ever seen “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West”? I have been to see it and think it is great fun. You see lots of Indians and “Cowboys” and “Buck jumpers” that are awfully naughty and the Cowboys can hardly ride them . . . it is so funny. We have got some canaries that Mama [got] us and I think they are cunning.41

Of course the girls also played at home, as evidenced by the doll Julia holds in Sargent’s portrait - perhaps even the same one she mentioned in her letter. The toy is of a new and modern type, the baby doll, first created in the mid-nineteenth century and manufactured in both France and Germany. Julia’s appears to be of the German variety, made out of molded composition (a mixture of pulped paper and other materials) and fabric. Immensely popular and relatively inexpensive, such dolls were distributed throughout Europe.42 Whether or not it was meant to be a baby, and no doubt to the amusement of others, Julia had named her doll Popau - the nickname of Paul de Cassagnac, a contemporary right-wing politician, journalist, and renowned duelist with sword and pistol who figured in the recently opened displays at Grévin’s popular waxworks.

Ned’s diaries show that he and his wife shared in their daughters’ activities, both indoors and out. Isa took them driving and to concerts; Ned accompanied them on long walks and read to them in the evenings. In summer, at whatever resort they inhabited, he often went swimming with them. In an age before antibiotics and systematic inoculations, the girls were frequently ill; their father mentions their various colds and other ailments with concern. In 1881, Henry James wrote to their mutual friend Etta Reubell in response to her report that the girls had the measles: “I should fear that those white little maidens were not suited to struggle with physical ills - their vitality is not sufficiently exuberant.” He added that he hoped the worst was over, for “it can’t have amused Mrs. Boit and it didn’t amuse me either, not to be able to see her.” Three years later, James heard that “Mrs. Boit has scarlet fever among her long white progeny.” 43 James’s characterization of the girls - little, long, white - suggests that they were passive and weak, lacking the physical energy and high spirits of many children of their age; but perhaps in James’s mind, the little girls’ personalities were overshadowed by the brilliancy of their vivacious mother.

Like most expatriate girls of their age and class, the Boit daughters were schooled at home under the guidance of a governess or tutor. But academic excellence was not the goal; Wharton later claimed that she “had been taught only two things in [her] childhood: the modern languages and good manners.”44 The girls would have learned languages - certainly French, in which they were all fluent, but also German and Italian. They would have been enrolled in dancing classes, a necessary part of their social education, probably starting their lessons in Paris. The Boits also loved music and each played an instrument, a typical accomplishment for young ladies and a necessary one for domestic entertainment. All of the girls were skilled performers, and they often joined together to present private evening musicales, sometimes with proper programs carefully illustrated by Julia, who had a talent for drawing. They favored pieces by contemporary French and German composers - elegies and nocturnes written for their chosen instruments. Music served as both a pastime and a consolation throughout their lives.

When their portrait was painted in 1882, the Boit sisters would still have been perceived as children. Even the eldest, fourteen-year-old Florie, who leans against the vase in the background, still wears her hair down and her skirt at midcalf, only a bit longer than that of her younger sister Isa, whose skirt falls just below her knee. Some etiquette advisors suggested that girls of thirteen should wear ankle-length dresses, indicating their progression toward adulthood. Then, as now, many girls sought to speed up the process, wearing their hair up and their skirts long - and even adopting corsets - as soon as they could get away with it. How the Boit girls felt about such things is unknown; their cousin Mary was eager to lengthen her skirts when she turned thirteen, as other girls of her age had done, despite (or perhaps because of) the objections of her stepmother.45 If the girls or their mother had kept diaries (and if so, had their journals survived), such questions might be more easily answered. As it is, their father and uncle recorded few such intimate and feminine details. In April 1885, Ned noted that Florie and Jeanie “had their hair done up by Maxine,” presumably in an adult style. In July 1886, he wrote that Isa (mère) had allowed eighteen-year-old Florie to drive after lunch; his entry is marked with an exclamation point, as if the event were a momentous occasion.46 Despite these signs of maturity, the four girls remain forever young in Sargent’s portrait.