Читать книгу Errol Tobias: Pure Gold - Errol Tobias - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеSport and race in South Africa: A short history

South African sport, you could say, was born in politics. Politicians meddled with sport from very early on in the country’s history. The issue of race in national teams was a particularly thorny issue.

Take Cecil John Rhodes, arch-imperialist and erstwhile premier of the Cape, who rejected the speed bowler Krom Hendricks from joining the South African touring team of 1894 who had been on their way to England. Hendricks had to stay home although he was widely considered one of the best speed bowlers of his time.

His only ‘sin’ was the colour of his skin.

Some suggested that he join the team as baggage handler, according to Dean Allen’s Empire, War & Cricket in South Africa. But Hendricks was not a fan of the idea that he should humble himself in that way. A.B. Tancred, a member of this team sponsored by Rhodes, was angered by the fact that Hendricks refused to carry his teammates’ baggage and possibly participate in a match or three if the circumstances were right. It wouldn’t simply be unthinkable to play with him as an equal, Tancred said. According to him it would also have been unbearable.

Such attitudes regarding athletes of colour eventually became the norm in white South African society. They could not participate with white people in sport at all, regardless of how good they were. The possibility of so-called multiracial or mixed teams was unthinkable to the majority.

The situation got worse in the years of segregation in the first half of the 20th century, until it was entrenched in law after the National Party came into power in 1948 with its apartheid policies.

South Africa’s sporting competitors accepted this state of affairs because international sporting bodies were generally also controlled by conservative white people. They continued to play against white South African teams and excluded people of colour in their own teams. The New Zealand Rugby Union excluded Maori players in the 1949 and 1960 teams that came to South Africa, as it had done in 1928.

The silent approval of South Africa’s racial and sporting policies could not last much longer, however. The era after World War II and all its atrocities was, after all – unlike the situation in South Africa – one of equality, freedom and human rights.

Pressure from outside began to make international sporting authorities think differently. The Springbok touring team of 1960–61 through Britain and France ran up against protestors. It was on a small scale when compared to the resistance that Springbok teams would encounter in later international tours, but it was proof that there were people dissatisfied with South African racism, including in sporting arenas.

In New Zealand, public ire grew regarding the exclusion of Maori players in teams touring to South Africa. The way New Zealand’s rugby authorities humiliated their countrymen time and again to fall in line with South Africa’s racial policies started to sway opinion towards breaking ties with South African sport.

It didn’t stop at protests and public statements. In 1960 South Africa took part in its last Olympic Games for more than 20 years. The International Federation of Association Football (Fifa) kicked South Africa out. White South African teams were clearly no longer welcome everywhere in the world.

This resistance sometimes led to laughable ‘reform efforts’ in South Africa. The government agreed, for example, that black boxers could be selected to represent South Africa, but they could under no circumstances travel on the same airplane as their white teammates. In an effort to soothe Fifa, the local soccer authorities suggested that a white team take part in the qualifying matches for the World Cup tournament of 1966 and that a black team could represent South Africa in the qualifying matches for the 1970 tournament. So black people could represent South Africa now and then, but never in the same team as white people.

This did not impress the rest of the world much. The resistance to South Africa’s racist sport policies increased. In 1963 the South African Non-Racial Olympic Committee (Sanroc) was founded so that, along with other South African exiles, it could give support to this campaign against racism in sport.

South African rugby was, at first, not much disturbed by international protests: In the first half of the 60s the Springboks toured in Britain, Ireland, France, Australia and New Zealand and hosted Scotland, the All Blacks, Ireland, the British Lions, the Wallabies, Wales and France. Rugby ties with Argentina were also renewed with a Junior Springbok team (1959) and a Gazelle team (1966) touring there.

The Springbok teams were still white and apartheid was clearly visible on the pavilions, where black spectators cheered for the overseas teams from their markedly worse seats (usually somewhere high up and just off the goalposts). This sometimes led to small altercations, but the rugby bosses didn’t much care as long as the Springboks were still in action.

But the uncompromising attitudes of the apartheid government at last came to affect South African rugby relations in the international arena too. The Springbok touring team of 1965 was still in New Zealand when Dr H.F. Verwoerd, then the premier, made it clear in his infamous Loskopdam speech that Maoris would not be welcome as members of the All Black touring team scheduled to come to South Africa in 1967.

The tour was cancelled.

For many South Africans it was a shock. The French agreed on short order that they would replace the All Blacks, but the damage was done. What to do when one of your faithful rugby friends refuses to play against you? The government of B.J. Vorster realised that it had to make careful concessions if it didn’t want South African rugby to be exiled in the same way as other sports. Not long after Vorster said that the English cricket team would not be welcome in South Africa with South African-born Basil D’Oliveira in its ranks, he agreed that the All Blacks could include Maori players in its line-up for the tour of 1970. They would be allowed to tour as ‘honorary whites’.

The Springbok team would, however, remain white.

The concession about Maoris was too much for some of Vorster’s supporters and contributed to the split in the NP that led to the founding of the far-right Herstigte Nasionale Party in 1969. Later in the same year it also became clear how unpopular South Africa’s racist laws and sporting policies actually were when the Springbok touring side of 1969–70 was met everywhere they went in Britain with levels of protest they had never encountered before.

Thousands of protestor overwhelmed the Springboks’ matches to signify their stand against apartheid. Peter Hain, a South African expatriate, was one of the protest leaders. The protestors clashed with the police, made a racket outside of the Springboks’ hotels, and threw sharp objects like nails onto the playing fields. There was fear for the players’ lives.

White South African propaganda, especially from the radio commentator Gerhard Viviers, tried to dismiss the protestors as worthless hooligans who were paid to demonstrate. Some of them didn’t even wash their (greasy, and of course long) hair, listeners were told match after match, and supposedly didn’t even know what or who they were protesting against. Such emotional statements tried to lead the attention away from the true issues. Many knew better.

For some the price of friendship with South African rugby started becoming too high. Even age-old traditional rugby friends started to back away from contact with South Africa. The match against Scotland in 1969 was South Africa’s last for nearly 25 years against the Scots. The one against Wales was the last for almost 24 years. A Springbok team would be welcomed in England again only in 1992.

Such pressure led to more small concessions. In 1971, Roger Bourgarel, the French wing, was the first black player allowed to come to South Africa and play against the Springboks. (He also forced certain people who believed that black people were not good enough to compete with white people to swallow their words when he flattened their great hero Frik du Preez on the corner flag.) But small concessions were no longer nearly enough.

The Springbok tour through Australia in 1971 was the major proof of this. The protests were even greater than those that left the Springboks astonished in 1969–70. Unions refused to handle the Springboks’ luggage on airports, clashes between protestors and the police were an everyday occurrence and matches were interrupted by protestors storming the fields. A state of emergency was declared in the state Queensland. In addition, six Wallabies declared publically that they were not prepared to play against the Springboks. Among them was the wing Jim Boyce, who in 1963 saw the effects of apartheid first-hand as a member of the former Wallaby touring team in South Africa. Jim Roxborough also changed his point of view about South African rugby after his experiences on the Wallaby tour in 1969.

Such opposition from players was no longer strange by this point. The All-Black scrumhalf Chris Laidlaw regularly made public statements to express his opposition to South Africa’s racial policies after the tour of 1970. Welsh players such as Carwyn James, John Taylor and Gerald Davies also refused to play against the Springboks. In 1968 Davies experienced apartheid first-hand as a member of the Lions touring team. It caused him to decide that he would stay out of South Africa in 1974, when the Lions – despite increasing opposition at home – came to tour in South Africa once more.

After the Australian tour, the doors for South African sport began closing ever faster. The Springbok cricket tour to Australia was cancelled and Gough Whitlam, Australian premier, broke all sporting ties with South Africa in 1972. The Springboks and Wallabies would only compete again in 20 years. The Springboks were only welcomed into Australia in 1993. New Zealand was also no longer prepared to host the Springboks in 1973.

In the ranks of white South African rugby, new plans were being made to defuse this situation. Dr Danie Craven, president of the South African Rugby Football Board (SARFB), was no radical reformer. His plan was never to try and implement radical change in South African society or to undermine the political system. He did realise, however, that without concessions, South African rugby would only grow more isolated. It was necessary to include people of colour as players within the limiting framework of the apartheid laws and the rules of white rugby. The South African Rugby Football Federation (for coloured players) and the South African Rugby Association (for black players) worked with Craven.

The South African Council on Sport (SACOS), which campaigned since 1973 for non-racial rather than multiracial sport, and the South African Rugby Union (SARU) did not want to lend legitimacy to the minor reforms that were still based on the principle of segregation and led by the white rugby bosses. SARU organised its own competitions and chose its own representative teams. Any contact with the SARFB and its affiliates was taboo. SARU could suspend players or officials merely for watching matches of the SARFB-group. For example, Rob Louw, a white Springbok, was occasionally denied access to the pavilions of a SARU match. Players of colour outside the SARU-affiliates were dismissed as ‘token’ and ‘honorary whites’. Insults such as ‘traitors’ were also used. SARU also believed in the slogan: No normal sport in an abnormal society.

How can you, SACOS and SARU rightly asked, be good enough to play with whites but not to have a few drinks with them after the match or to stay in the same hotel? Unless you humiliated yourself by asking the government to temporarily be declared an ‘honorary white’.

Teams like the (coloured) Proteas and (black) Leopards were ‘rewarded’ at the beginning of the 70s with tours to England and Italy. They also played against the English touring team of 1972 and the British Lions in 1974. A representative, multiracial South African team only played against an overseas opponent in 1975 when Morné du Plessis led South Africa’s fifteen-man team onto the Newlands field to play against the French touring team. A similar team played against the All Blacks a year later when the New Zealanders’ tour coincided with the widespread protests by black youth in Soweto schools. The New Zealanders’ tour also led to a massive boycott of the Olympic Games in Montreal by African countries. A year later, there were mixed Springbok trials for the first time. Black and coloured players were taken into representative teams that played in the inauguration of the new Loftus Versfeld fields.

But the Springbok team stayed white for the test against a world team on the new Loftus in 1977.

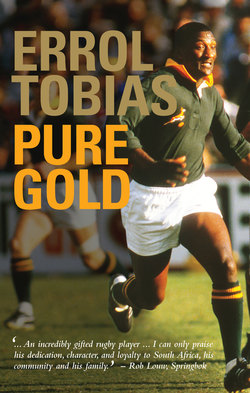

The first international tour by a multiracial South African rugby team came two years later. This South African Barbarians team consisted of eight white, eight coloured, and eight black players. At the time it was seen as a major breakthrough for multiracial sport in South Africa and some were of the opinion that it paved the way for the British Lions tour of 1980 in South Africa. A multiracial South African fifteen-man team went up against the Lions again in that year. Errol Tobias also played in a multiracial Junior Springbok team that played against a Barbarian team. Hugo Porta, the famous Argentinian fly-half, was his opponent. The spectators in Pretoria left no doubt about their opinion on the winner of this clash: Tobias got a standing ovation for his top-notch playing. Not long afterwards, the last bastion of white South African rugby began to topple when Tobias became the first black Springbok in 89 years. Craven had finally managed to get his way after he previously had to give way under pressure when he wanted black representation in Springbok teams. (If one follows the racial classification system of the apartheid government, Tobias would be the first coloured Springbok. The liberation movements generally termed everyone under apartheid as ‘black’, until they also began to think in more divided terms.)

Tobias was a member of the first Springbok touring team to travel internationally in six years; a team that had to go by the back routes of South American rugby to play in countries under the rule of dictators such as Paraguay, Chile and Uruguay, and which came up against an Argentinian team twice that disguised itself as the Jaguars for political reasons. Regardless of the Springboks having their first black player in more than eight decades, they were still not welcome in Argentina. The Argentinian government didn’t even want to allow its team to play in other colours or elsewhere on the continent or in the world against the Springboks.

Tobias did not play in a test match on this tour. He made his test debut the following year (as a centre) against Ireland on Newlands. He also played in the second match in Durban and his performance made him a sure choice for the touring team of 1981 to New Zealand. It was the first Springbok tour in 16 years and no one really knew what to expect. It was certain that there would be resistance. Activists in South Africa and New Zealand were heavily opposed to the tour. An organisation called Halt All Racist Tours spearheaded the opposition to the Springboks touring in New Zealand. But it wasn’t only political activists that made the Springboks feel unwelcome. A petition with more than 3 000 signatures from residents of Auckland and Dunedin requested that the Boks stay out of their country and was sent to SARFB. It was known as the ‘Book of Unwelcome’. Bruce Robertson, an All Black that toured in South Africa in 1976, refused to play against the Springboks. So too did Graham Mourie, captain of the All Blacks. Naive South Africans believed that the presence of Tobias and Abé Williams, one of the officials on the tour, would be enough to undercut resistance; to show that the South African rugby authorities were serious in their intentions to move away from apartheid; to attempt to make rugby normal in an abnormal society.

This could not be further from what happened. New Zealand was torn in two by protests. It was a small civil war with the police in the middle. Violent clashes were the order of the day. The Springboks watched powerlessly in Hamilton from the pavilion as protestors occupied the field and the match was cancelled. Another match was cancelled due to safety concerns. Pieces of glass and smoke bombs were thrown onto the fields. Stadiums were fenced off with barbed wire and guarded by the police. A special police unit was founded to protect the Springboks. The team frequently couldn’t even sleep in hotels and at one point had to sleep in a squash court. The third test in Auckland was preceded by bloody clashes between the police and protestors in the streets around the stadium. A light aircraft swooped down on the players during the match and dropped flour bombs on them. One of them downed Gary Knight, an All Black prop.

A short visit of three matches to the United States of America also led to protests. The first ever test match between South Africa and the USA was an example of the precarious international position the Springbok team found itself in. It was played in secret on a polo field. A little over 30 people (estimated) watched the match. Even members of the touring team didn’t know the match was being played. And that in the USA, a country that, unlike New Zealand, was not well-known for its rugby.

The tour of 1981 by New Zealand and the USA closed nearly all doors for South African rugby for good. The Springboks were in action only five times over the following decade: twice against the Jaguars, once against England, hosting a rebelling team from New Zealand in 1986 (the Cavaliers) and in 1989 played two tests against a world team to celebrate the centenary of SARFB. The All Black tour of 1985 was cancelled and the Springboks were forced, in that year of states of emergency and increasing political unrest, to tour South Africa in matches where they were not to wear official national colours. The British Lions also decided to cancel their tour in 1986. In 1987 a team from the South Sea Islands, the South Sea Barbarians, toured South Africa. They didn’t even play against the Springboks.

The tour of 1981 was anything but a highlight for Tobias. He also received criticism because they saw him as an ‘Uncle Tom’. The utterly inappropriate way he was treated by manager Johan Claassen and coach Nelie Smith is infamous. He did not let this stop him. His biggest Springbok moment came three years later with the English team touring through South Africa. He was 34 years old then – a touch over the age range for a running back, especially a fly-half, was muttered in certain circles. But which true rugby connoisseur would ever forget the way Tobias played in the Proteas against the English? His deadly corkscrew runs where he sometimes teased the English defenders by holding the ball out to them, as if daring them to take it from him. ‘Errol Tobias is not coloured,’ the English coach, Dick Greenwood, observed. ‘He is pure gold.’ The second test in Johannesburg was quite possibly his best while wearing a Springbok jersey. At Ellis Park he reached yet another milestone in becoming the first black Springbok to score a try for South Africa in a test match. By this time, Tobias was no longer the only black Springbok; the wing Avril Williams also played in two tests against England. Today one can only wonder how many other black players during the years of apartheid could have made the kind of contribution to the Springboks as Tobias and Williams did if the principle of normal sport in a normal society held true.

This slogan finally became a reality in South Africa towards the end of the 20th century, with the first democratic election resulting in the majority rule. Many observers of South African history would say that the pressure that organisations like SASCOC and SARU brought to the table helped to speed up the end of apartheid. They would not be wrong. They would ask if people such as Tobias truly accomplished the same. He didn’t change society, after all, they would say. Again they would not be wrong. He did play for the Springboks. But the society in which he lived was anything but normal. It did not even have the illusion of being normal: Tobias was severely limited as to where he could live, where he could work and for who, where his children could go to school, where he could go on vacation, where he could buy groceries, who he could vote for. Like many other South Africans, white people included, he couldn’t even read what he wanted to. The white government could decide where he could go to the hospital and where he would one day be buried. Nearly three years after Tobias played his last test for the Springboks, he couldn’t even swim wherever he might like to. Even if you were a cabinet minister like Reverend Allan Hendrickse.

Someone like Tobias was also not accepted everywhere in his own rugby world. White players complained about him. Officials were openly hostile towards him. In 1987 two rugby bosses (Boetie Malan from Northwest Cape and Daan Nolte from East Transvaal) announced that they were electoral candidates for the Conservative Party (CP). The CP, under the ultra-conservative leadership of the former scrumhalf of the Southwest District, Dr Andries Treurnicht, did not believe in normal sport in the least. They actively wanted to keep society and sport abnormal. The Conservatives were, among other things, heavily opposed to mixed Craven Week rugby teams. Springbok teams with Tobias and Williams in the ranks stuck in their craws.

The fact that Tobias played his rugby in a largely racist society and, according to some, was cynically abused by the white rugby bosses to mislead the world about the true state of affairs in South African sport, is still sometimes held against him. But the judgment of history is never that simple; even if it is only sporting history. Tobias’s tale has another side. It must be told and read. It is a story that tells of a man that struggled for his whole rugby career against prejudices and an unfair system. A brave and talented man who leapt on the small chances offered to his career and used them. A man who crossed borders, racial borders, in his divided country where no choice was ever easy. Unlike SARU players and officials who were mostly faceless and anonymous to white people during the apartheid era, easily dismissed as ‘agitators’, Tobias was on the rugby fields and television screens. He proved that black players were just as good, if not better, than white players. For that reason an older white man would, years later in an airport restaurant, want to shake Tobias’s hand for providing him with so much rugby pleasure, because he helped to open eyes, to change attitudes. For that reason spectators on Loftus Versfeld got to their feet to cheer him on. For that reason white boys from a conservative Free State dorp like Hoopstad were already standing in line in 1980 at the Free State stadium just to touch Tobias or get his signature; something that was nearly unthinkable in the South Africa of those days. I know. I was one of them.

For that reason Tobias should perhaps be judged the way an English daily newspaper based in Cape Town did in 1903 with the centre Japie Krige. Krige was one of the South African rugby heroes when a British team came in 1903, barely a year after the Anglo-Boer War, to tour through a South Africa with a divided (white) population. With each step Krige took on the rugby field, the newspaper said with perhaps a touch too much enthusiasm in one of its editorials, he did more than all the political speeches to bring closer together English speakers and Afrikaners. With each step that Tobias took on the rugby field, he helped to ensure that decades later the borders between white and black would break; just like the SARU players such as the Watson brothers, expatriates and political activists helped to chip away piece by piece at the wall of apartheid. Perhaps history will remember him for that, one day, rather than anything else.

Gert van der Westhuizen

Sports editor of Beeld