Читать книгу Errol Tobias: Pure Gold - Errol Tobias - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

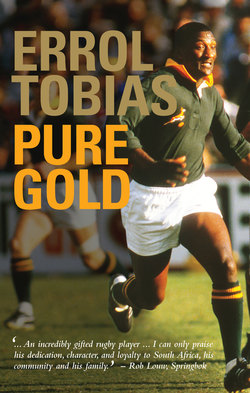

I WAS 30 years old in 1980 when I was chosen as the first person of colour to put on the green and gold jersey of the Springboks.

I worked hard and sweat blood and held on and persisted to realise this childhood dream. Not only to be the best attacking fly-half in the world, but also to prove to the sceptical white people of the time – rugby supporters and also some of my teammates – that we are all equal, that your skin colour doesn’t matter, and that if you have the talent and skills, you should be allowed to represent your country at the highest level.

Of course, it wasn’t only the white community that was against my inclusion in the Springbok team. Many of my own people and other South Africans who were denied the right to vote in those days, anti-apartheid activists such as archbishop Desmond Tutu, and international critics wrote me off as a token, an ‘Uncle Tom’, a sell-out, a traitor that allowed the white rugby management to ‘abuse’ me for political purposes in an effort to soothe their conscience, as well as appease the world and to relieve the political pressure on South Africa.

These people were blinded by fury because I was prepared to wear a Springbok jersey – ‘the great status symbol of the apartheid regime’ – while playing rugby all over the world. In this way, according to my critics, I helped to justify an unfair, inhuman political system.

But to this day, I don’t regret a single decision I made. I still feel exactly the same as in those days: I was a sportsman – not a politician. I could play rugby, but didn’t have the right to vote or any say in politics – in the same way as the apartheid regime and their inhuman laws didn’t have any say or control over my sporting talent.

Just as in those days, I still believe that no national team – yes, not even the Springboks – should be selected for political purposes. A national team is selected to play in an international test and to preferably win that test. And in a test like this, you don’t just play for yourself; you play for your people, you play for South Africa.

That Springbok blazer my critics resented me for at the time, was and still is my joy, my pride and my honour for which I went down on my knees and praised God – nobody can ever take it away from me.

But by no means am I trying to suggest that apartheid wasn’t a horrific political system. Of course, I was also of the opinion that apartheid is evil, but I wanted to show South Africa and the rest of the world in my own way and by my own talents that black players are just as good as white players, if not better.

SINCE MY RETIREMENT 30 years ago, rugby supporters have often asked me when I will write my autobiography. On the one hand, I have always believed that what happens on rugby tours should stay behind closed doors for that select group who experienced it. But this book, on the other hand, is the realisation of one of the late Dr Danie Craven’s (1910–1993) master plans.

Doc Craven, the longest-serving chairman of the South African Rugby Board (since 1956 until his death), is one of my great heroes. Critics often refer to something Doc apparently said a long time ago that black people will play in a Springbok jersey over his dead body, but for me he was a genuine pillar of strength who supported and encouraged me throughout my career. He was the one offering support with every underhanded scheme or political storm that hit me. ‘Errol, I hope you are making notes, because this political mess will serve as material for your book.’ He was also the one who advised me to wait at least 30 to 35 years before putting pen to paper.

‘Why such a long time?’ I wanted to know.

‘Well, not only will you then be wiser and understand why you had to overcome all these obstacles, but hopefully the people who now hold you in such contempt will judge you again and realise the groundbreaking work you did.

‘In 30 years South Africa will be a totally different country from the one we know now: a country with a new black government, a country where everyone has the right to vote. But remember one thing: Politicians are actually all the same … I hope you won’t be too shocked and disappointed in the future about how little things will change in these 30 years …’

And how right Doc was! So let’s call a spade a spade: What have coloured and black players really gained from the right to vote? Surely not more exposure and opportunities to play at international level …

THE SPRINGBOKS are still white. Much too white. Politicians are still being politicians. Racism is still rampant. And what happened to me and other coloured players in those days is still the order of the day. In 1984, Avril Williams and I were the only coloured players in the Springbok team; during the World Cup in 1995, there was only Chester Williams; in 2005, Breyton Paulse and Bryan Habana got the opportunity; and now we have the intolerable situation where two really talented players such as Gio Aplon and Juan de Jongh are not getting contracts and will probably seek their fortune overseas …

For this reason the targets set out by the South African Rugby Union (SARU) in its latest strategic transformation plan – among other things, to ensure that by 2019 at least half the players at Springbok, Super Rugby and Curry Cup level are black – should be welcomed with open arms. But, as I explain at the start of 2015: Where do we stand today?, quotas are not the solution. At international level, merit is the only thing that counts.

IN THIS BOOK I share the highs and lows of my career as I experienced it. Without beating about the bush. Without big words. Without having an axe to grind. Without political mudslinging. The only thing I want to achieve is to share my journey through rugby and to hopefully stimulate lively debate in the process and help rid the system of shortcomings and deficiencies, in order for South Africa – and especially South African rugby – to achieve even more.

Errol Tobias

15 May 2015

Treasured words

Several people have supported me during my career. Here are a few quotes that I still cherish to this day.

| ‘Errol, some people don’t appreciate you yet, but this will change the day you are not with us anymore. This you can be sure of: Your children will taste success.’ – Former president Nelson Mandela during a private dinner at Genadendal, the presidential residence in Cape Town |

| ‘The Afrikaner believes in apartheid, but also in hero-worship. They will give you the credit you deserve, but based purely on your performance as Springbok.’ – Doc Danie Craven |

| ‘When your biggest enemy is covered in mud, don’t trample him further into the mud. Hold out your hand and help him up – you never know when and where you might need his help in future. Rather part as friends.’ – Josef, my father |

| ‘Control your emotions. The joy of tackling a white opponent shouldn’t be everything. Play the ball, not the man. There is no greater joy than leaving the field with more points on the scoreboard. Help your opponent up after a tackle. Show self-respect and don’t lose your dignity.’ – Dougie Dyers, rugby coach and administrator |

| ‘God loves you; you are blessed with the words “the first” … Therefore make sure that whatever you do serves an honourable and worthy cause.’ – Professor Daan Swiegers, former Springbok team manager, after I became the first person of colour to score a try for the Springboks |

| ‘Errol, I don’t like your style of play, but I have to pick you because you are the best and honourable in what you do. – Oom Abé Williams during the Proteas’ tour of Rhodesia in 1980 |

| ‘Finally South Africa has a fly-half that can catch, pass and break.’ – Former Springbok Jan Boland Coetzee after the Proteas’ game against England on 23 May 1984, Die Burger |