Читать книгу A Calculated Risk - Evan M. Wilson - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOREWORD

ОглавлениеWilliam B. Quandt

Edward R. Stettinius Professor of Politics

University of Virginia

What can we learn today from looking back at the fateful decision made in the late 1940s by a small group of American officials to recognize Israel as a predominantly Jewish state in a part of what was then British-mandated Palestine? The events must seem far away to many Americans whose awareness of the Middle East and its many traumas dates from a more recent period. And yet the more we probe the issues of today, the more we realize that, for the players most involved in these events, questions of history are not abstractions; on the contrary, historical memories, or reinventions of history, are part and parcel of the narrative of current conflicts. So Americans who wish to understand the present problems of the Middle East would do well to brush up on their history.

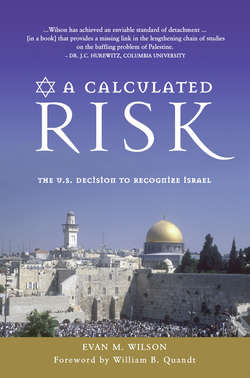

One excellent place to start is with Evan Wilson's even-tempered book A Calculated Risk. Wilson was a Foreign Service Officer who spent some thirty years of his career working on various aspects of Middle East affairs. His book covers the crucial years from the early 1940s through the declaration of statehood by Israel and America's decision to recognize and support the new state. For much of this period, he was an insider, but he does not limit his account to what he was able to observe. He also consulted the available archives and interviewed many of those who participated in the decisions of the day. His account is both well informed and well written.

Wilson is also frank to admit that he was opposed to the main thrust of American policy at the time, and he spells out his reasons, and those of his like-minded colleagues. At a time when it is almost unheard of to question the decision of President Harry S. Truman to recognize Israel, it is worth examining the reasons of those who took a different position. It is too easy, and fundamentally untrue, to say, as some have done, that they were merely anti-Zionists (perhaps even worse, anti-Semites). After all, among those who were skeptical about the wisdom of recognizing a Jewish state in Palestine were a substantial number of illustrious foreign policy leaders—Secretary of State George Marshall, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, Robert Lovett, Dean Acheson, Dean Rusk, George Kennan, Loy Henderson, and many who were less well known.

What may surprise readers of this book even more is the evidence that even President Franklin D. Roosevelt seemed to harbor some doubts about rushing to recognize a Jewish state, as did the man who made the final decision, President Truman. In short, the issues at the time were seen as complex, debatable, and not at all as clear-cut—in either moral or strategic terms—as they may seem today.

Wilson's account shows that the decision on Palestine was not made without prolonged discussion and a high-level of awareness of the stakes. From about 1942 onward, it was clear that the United States would play a central role in determining the face of the post-war Middle East. Great Britain and France might control most of the territory in the region, but the power realities were clear—the United States, having emerged from its isolationist stance, would have an unprecedented voice in setting up the post-war order.

The Zionist movement, ably led by such men as David Ben Gurion and Chaim Weizmann, recognized the importance of American support, and from late1941 onward they sought to win over American support to their cause. There is a story of Ben Gurion coming to Washington to meet FDR. As Glenn Frankel tells it:

“All David Ben Gurion wanted was 15 minutes of Franklin Delano Roosevelt's time. Israel's founding father, one of the indomitable political leaders of the 20th century, came to Washington in December 1941 yearning to present the case for a Jewish state directly to the American president. He took a two-room suite at the old Ambassador Hotel at 14th and K for $1,000 a month and cooled his heels for 10 weeks, writing letters and reports and making passes at Miriam Cohen, his attractive American secretary. But Ben-Gurion didn't get the meeting. Not then, not ever. Not even a pair of presidential cuff links.” (The Washington Post, July 16, 2006, p. W 13).

How times have changed. Of course, FDR had other things on his mind in December 1941 than the troubles in the Middle East. Still, it is inconceivable that any president in recent memory would refuse to see such a prominent leader of the Zionist movement, the future prime minister of Israel. But times were indeed different. The United States was faced with a truly global war, the politics of the Palestine issue had not yet become so deeply involved with American domestic politics, the awareness of the tragedy unfolding for Europe's Jewry was not widespread, and the concern of Arab parties was rarely heard.

It is striking to read this account of that period and to see how different the policy-making process was in those days. The State Department was literally across the street from the White House (in the Old Executive Office Building)—it moved to its present location in 1947. The number of people working on Near Eastern affairs was small—perhaps a dozen. It was not unusual for these officials to talk directly to the secretary of state or even to the President. And of course they were mostly of similar backgrounds—middle-aged male WASPs, often the products of east coast colleges.

Why were so many of these officials opposed to the idea of a Jewish state? The reasons varied, but several themes stand out. First, no one thought that the Arabs could be persuaded to accept a Jewish state in their midst. Any effort to create one would result in violence and it was not a sure bet how the ensuing struggle would turn out.

The experts were right about the resort to violence, but probably underestimated how well the Zionists (and then Israelis) would acquit themselves on the battlefield.

A second concern, especially acute by 1947, was that the Soviet Union, now clearly the major geo-strategic rival of the United States, might exploit the Palestine issue to extend its influence into the Arab world. The Soviets had already made their interest in Iran and Turkey known, and the United States had pushed back successfully. But there was real concern on the part of most of the State Department leadership—not just the Arabists—that the Soviets would exploit the creation of a Jewish state to their advantage. Playing on Arab resentments, they would eventually succeed in winning influence in the heart of the Arab world. That was seen by many, including the Arabists, as a strategic challenge. It is now clear that this was a legitimate concern, although the Soviets eventually lost the influence they so carefully cultivated during the period of the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s.

Some of those opposed to the idea of a Jewish state were also concerned with the moral problem of dispossessing an indigenous Palestinian Arab population who would inevitably become a minority in part of a land that had been theirs for centuries. There was a streak of anti-colonialism among those who led the State Department in this era—it applied to the British and French in particular—and Zionism was seen by some as simply a recent version of the old, and now discredited, colonial adventure.

Finally, for some, such as Secretary of Defense Forrestal, there was the matter of oil. With the end of the Second World War, there was an acute awareness among some American officials that the rebuilding of Europe and Japan would depend upon a reliable supply of oil from the Middle East. It was also important that U.S. military forces, especially the Navy, have secure access to oil. And Saudi Arabia was by now clearly a giant in the oil business—and American companies produced all of the oil in the Kingdom. The companies, interestingly, do not seem to have lobbied in any obvious way against the Jewish state, but those who worried most about oil were also worried about the effect of U.S. support for Zionism on access to oil supplies. In subsequent years—especially during the 1973 crisis—this proved to be a real issue.

While the arguments against the Jewish state were spelled out in detail within the American bureaucracy, it was at the White House that the decision would ultimately be made. And there the considerations were often colored by domestic politics, as well as the strategic concerns raised by Marshall, Lovett, and Forrestal. Truman in particular found himself caught between contending forces. He certainly heard and understood the concerns of those who opposed recognition of Israel. But he also heard from friends and fellow democrats who favored Zionism. In the White House, David Niles was a conduit for those views, as was Clark Clifford. Truman admits in his memoirs to feeling heavily pressured on the Palestine issue, which he resented, but through some combination of moral and political reasoning he eventually came to the conclusion that support for Israel was the right course.

Part of Truman's problem was the lack of real alternatives. The British had tried during the mandate to come up with proposals that would satisfy both Zionists and Arab nationalists. There simply seemed to be no middle ground. And the British decided in early 1947—under dire pressures to contract their overseas commitments—to throw the Palestine issue into the lap of the newly created United Nations. The United Nations, of course, was unprepared for this challenge. The partition plan that the General Assembly was barely able to agree upon in November 1947—after intense pressure from the United States on some very small and easily-manipulated member states—was never going to be implemented peacefully.

After the vote on partition, the question arose of how the resolution could ever be implemented. This led to a proposal, briefly endorsed by the United States, to support a transitional period during which Palestine would be place under a U.N. trusteeship. This might have postponed the moment of reckoning, but it won no support from either Zionists or Arabs. The truth is that both sides preferred to take their chances on the battlefield rather than to count on untested international institutions to resolve a conflict that was existential for each.

Given the speed with which the United States finally recognized the new state of Israel in May 1948, one might have thought that Washington would also have become Israel's major financial and military backer. But Truman was only willing to go so far. He did not authorize arms shipments to the new state, despite his sympathy for it. It is hard to remember that for the first twenty years of Israel's existence, the United States actually had a somewhat standoffish relationship, manifested most clearly in its unwillingness to give Israel either arms or a blank check. This was a residue of the strategic arguments that had been made, largely at the State Department, against too close an embrace of Israel for fear of providing openings to the Soviets and of undermining pro-Western Arab governments.

At the moment of writing this Foreword, a noisy debate is taking place in the United States about the influence of the pro-Israel lobby. What is striking about the period under review is that Zionists did indeed manage to have considerable, probably decisive, influence over Truman's decision, but there was hardly anything at the time resembling today's well-organized and well-financed lobby (most visibly, but not solely, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC). Instead, Zionists sought and managed to win access to the White House and to Truman through personal contacts. Truman's former business partner managed to get Weizmann in to see Truman at a crucial moment; Felix Frankfurter, a staunch Zionist, was a close friend of Truman and other leading Democrats. In the Senate, Robert F. Wagner played an important role. And the American Jewish community, despite its small size, had begun to organize and make its weight felt.

Zionists were persuasive for many reasons, but certainly one was that they were able to portray their cause in terms that resonated with many Americans. On one hand, the Jewish people had suffered on an unimaginable scale, and the full horror of the Holocaust was becoming well known in the immediate post-war years. For many, this gave Israel a moral claim to a secure homeland as a refuge for the remnants of European Jewry. In addition, European-born Zionists like Weizmann quite literally spoke the same language as the American establishment. Their worldview, their values, their historical reference points were all similar. And finally, they had powerful allies in the American Jewish community, including those organized groups like the American Jewish Committee and the American branch of the Jewish Agency. Personalities like Louis Brandeis, Stephen Wise and Abba Hillel Silver also played important parts.

While pro-Zionist views were often challenged from those within the bureaucracy who thought they were looking after America's long-term strategic interests, it is striking that voices from the Arab world were rarely heard in official Washington. Nor did the small Arab-American community count for much. Only one Arab leader seems to have made much of an impression. In February 1945, FDR met with King Abdalaziz (Ibn Saud). The King was strongly opposed to Zionism and the idea of a Jewish state in Palestine. FDR apparently was impressed by his personality and some of his arguments. He later told colleagues that he learned more from that one meeting than from all the briefings he had had from the State Department. And he made a vague promise to the King, later repeated in endless diplomatic exchanges, that the United States would take no action on Palestine without first consulting the Arabs.

While the Saudi King may have made an impression on FDR, he was a man of another era and another ethic. He did not deny that terrible things had been done to the Jews in Europe. But his tribal view of how to compensate them—lay waste to part of Germany and let the Jews have their state there—was not likely to win many adherents in the United States. So there was really no dialogue with the Arab side of the argument. No one was very interested in the views of the new Arab leaders—King Faruq of Egypt, King Faisal II of Iraq, King Abdallah of Jordan, all beholden to Great Britain, or the rabble-rousing Mufti of Jerusalem, who had sided with Hitler in World War II. The Arab point of view simply had no resonance in official Washington, certainly not in comparison to that of the Zionists.

Sixty years later, much has changed in the politics of policymaking toward Israel/Palestine. But some things also remain the same. The White House is where the action takes place. Presidents do matter. All have supported Israel to one degree or another, but some, such as George W. Bush, have gone further in offering a virtual blank check. Public opinion remains generally pro-Israeli, and Congress is even more enthusiastic. The bureaucracy, stripped of most of its “Arabists”, still registers occasional dissents from straight-out support for Israel. There is still a concern for some degree of balance so that interests in the Arab world will not be placed at risk. And oil from the region is more important than ever. But strong support for Israel is now a sine qua non of American policy.

Gone is the fear of Soviet encroachment—a strong motivator for those who argued in the 1950s and ’60s that we should keep some distance from Israel. And there is the new phenomenon of extremist groups of Muslims such as Al-Qaida who are determined to strike directly at the United States.

But the Arab-Israel conflict is still there, unresolved, and familiar in its basic outlines to anyone who has read history. True, Egypt and Jordan have made peace. And President Bill Clinton came close to resolving the remainder of the conflict on his watch, but ultimately he failed.

The debate in Washington goes on, although less within the bureaucracy and more in the public arena. The Arab states are now better represented, some with very able spokesmen. The Arab-American and Muslim-American communities are better organized. The elite press is often fairly good in its coverage of issues, although there is still an obvious tilt in Israel's favor. And the pro-Israel forces, well-organized and well-endowed, have now been joined by significant numbers of Evangelical Christians who support Israel for religio-ideological reasons. The old notion that Democrats are more predictably pro-Israeli than Republicans has been demonstrated false by the presidencies of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. Being pro-Israel, especially in Congress, is one of the few issues on which Republicans and Democrats tend to agree.

With all that has changed since the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, some of the lessons that we can draw from Evan Wilson's book are still relevant. The United States has important interests on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict and the best way to protect those interests is to find a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Unfortunately, those simple truths are at risk of being lost amidst the rhetoric of “transforming” the Middle East and pursuing the Global War on Terrorism. No President can expect to tackle the fundamentals of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict without entering contested and controversial territory. That much we can learn from A Calculated Risk. But without a president willing to engage seriously with the complexities of the issues, and without strong American leadership, the conflict is likely to go on for many more years, poisoning the chances for a region of hope, of development, and of democracy. In a Middle East without peace in Israel/Palestine, American interests will remain at risk, much as Evan Wilson and his colleagues had feared.