Читать книгу No Worst, There Is None - Eve McBride - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4

ОглавлениеA Monday Afternoon in July 1986

Lizbett and Melvyn

Lizbett loves the rotunda of the Courtice Museum with its gold-and-turquoise mosaic floor and its soaring dome with the beautiful stained glass. She has been coming to this museum since she was in a stroller pushed by Meredith or Thompson, a Sunday afternoon ritual.

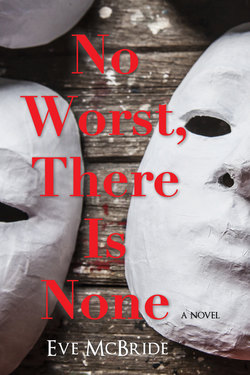

She is just returning from the Chinese garden where she has eaten her lunch with a couple of her campmates. She and her friends had thought they might get rained on, but they were lucky. They have come in early, in any case, to make a quick visit to the mask exhibits, something Lizbett does almost every day. She is in awe of the masks, of their tremendous variety and meaning in every culture. She likes what Melvyn has been telling her about masks: that a mask is something that hides a person, but is also an extension of that person. A mask has one face, but is two people: the one in it and the one it represents.

Lizbett gravitates to the very wild, primitive masks and also the Noh masks of the Japanese theatre. There is a maiden’s mask from Mali where the entire face is covered in white cowrie shells and draped over those is a heavy veil of hundreds of thin braids. On top of the head, the hair is formed into a tiara bordered in bright yellow and red beads. And beneath there is a collar of turquoise beads. The Noh mask that most attracts her is also that of a young girl. Playing a young girl was the highest challenge for a Noh actor and the masks only succeeded if the performer’s movements were natural and convincing. Lizbett imagines a man making this white doll-like face with the thin red lips and laughing eyes into someone the watchers believe is a happy, innocent girl.

It distresses Lizbett that in almost every culture, only the men wore masks. Even if women took part in a ritual or drama, their faces remained uncovered.

This morning Melvyn had gone over again what mask camp is about. It’s not just about making masks, he always says. “What else is it about?”

Lizbett’s hand shoots up.

“Lizbett?”

“It’s about what masks say. Like they can say who we aren’t as much as they can say who we are.”

“And how do they say who we aren’t?”

Again, Lizbett’s hand.

“Jesse?”

“Um,” Jesse says, “Sometimes they can be a fantasy of what we want to be, a self in our imagination. Like who we want to be. Like a king mask, or something. Or they can turn us into someone else who is real. Like a mask of someone famous. Or else they can show us to be scary when we’re really timid. Or happy when we’re really sad.”

“Or they can be a spirit or a god or something. Or maybe even an animal,” Laurie, in the back, pipes up.

“That’s right,” says Melvyn. “They can be representations, not of ourselves, but of what we believe. That also is a kind of indication of who we are. We’ve talked about the two-fold aspect of masks. Masks allow us both to deceive and believe at the same time. The person wearing the mask is the deceiver, but he is getting you to believe what the mask says. Masks can be us, but not us, as creations of our ancestors, our bloodline, or how we imagine them. Masks can be instruments of healing. Warrior masks protect against evil. A mask is a facade that gives us certain powers, the ability to act in ways we couldn’t act without it. But do people really believe the one wearing the mask actually becomes the spirit he’s portraying? Does that figure then become a way for someone to communicate with the spirit? Next week, our last week, we’ll examine spirit masks, masks that are stand-ins, masks that portray something unknown, something we don’t really understand. Something spiritual. A god or goddess. Something that might be worshipped or perhaps be a communicator between us and a higher force. And then we’ll create our own spirit masks from moulds of what we’re going to do today. So far, we’ve done two kinds of masks. The first week, we carved a mask out of clay to show a self from our imagination. An ideal self, a fantasy self. Last week, we went into our deepest selves to make a mask of an inner feeling, one that we could only express through an art form. We called that an outer creation of an inner core. Many people create invisible masks to hide feelings or their real identity. We created visible ones, ones that actually advertised an emotion.”

Lizbett thinks about the masks she has made. She has not found this course easy. She had thought masks were about disguises, like for Hallowe’en. But Melvyn has talked about each mask being a map and that making them is a journey of discovery. The first was a journey outside yourself, so you could see yourself as a fantasy. The second was a journey inside yourself to find a hidden or secret feeling. The first one was the real challenge.

“I really don’t know how to make a mask of how I imagine myself,” she said to Melvyn. “I sort of imagine myself as how I am.”

“Don’t you have hopes and dreams?” he asked.

“Well, I’d like to be an actress.”

“What kind of actress?”

“A really good one. A famous one.”

“And what do we call a famous actress?”

“Oh! A star! I get it. It doesn’t have to be realistic. It doesn’t have to look like me. It’s about a symbol of me as a star. Or a star as me.”

After that, Lizbett knew where she was going. She fashioned a plain, smooth face, out of modelling clay, like the Noh masks, because her face had to do or be anything and she wanted her body movements and words to tell the story. After the clay hardened, she painted it white and yellow with a thin gold overlay. And she arranged gold and silver sequins and little yellow jewels in patterns all over that. And then with curlicues of wire, she made a fancy halo, a tall headdress, and wound gold garlands and beads around it, ones she’d found at home in their box of Christmas decorations. And she hung spirals of gold and silver ribbon from the sides. Herself as a star. A star as her.

The second mask was less difficult, although in the meditation session Melvyn always did at the beginning of the class to help them on their journey, she was afraid she might start to cry because she was thinking her deepest feeling was from when their dog, Misty, had to be put to sleep. But that was the mask she wanted to do. A mask of the horrible sadness after something dies.

“Your mask comes from a feeling inspired by death?” Melvyn asked. “That’s very serious, Lizbett. A mourning mask. Are you sure?”

“It’s my deepest feeling,” she replied. “It’s a mask of tears.”

Tears are water, she decided. So she fashioned the saddest face she could imagine, borrowing a little from some carved wooden masks from Switzerland in the exhibit whose furrowed brows and sloping eyebrows and eyes spoke of real sorrow. Using papier mâché, fashioning eyebrows, eyes and mouth in a deep downturn, skin dripping, she painted the mask a pale blue and again used an overlay, but this time in silver. She drizzled clear silicone from the eye sockets. And she found in the trinket box, much to her delight, several little tear-shaped mirrors that she glued down one cheek. And this time she made elaborate, long, drapey hair from strips of blue fabric and silver paper. When she put the finished mask over her face and looked at herself, she actually felt sad. She could feel her whole body droop.

Then Melvyn talked about this week’s mask. “We’re going to do a special mask that is an exact representation of who we are. Now, how can a mask say who we are, as others actually see us not as we see ourselves? Anyone? Carla?”

“Well, we can make masks of how we think we look to other people.”

“Not how we think we look, how we really look. How do we get a mask to be exactly us?”

“Couldn’t we get a photograph of ourselves and model a mask of that?” offered Laurie.

Melvyn said, “Wouldn’t that still be just an interpretation of what you see? The same goes for modelling a mask of yourself from a mirror. How do you get a mask of how others see you?”

“I know!” volunteered Teddy. “You get someone else to make a mask of you by looking at you.”

“But,” replied Melvyn, “That would still be his or her interpretation, wouldn’t it? We want a mask of the real you, as you really are.”

The class was stymied. “Has anyone ever heard of a death mask?” Melvyn asked. No one responded. “Before cameras, people made death masks of their loved ones or someone famous at the exact moment of death by putting plaster over the face and molding it to the person’s features. That way they had a perfect representation of the person to remember him or her by. Why would that mean more than a photograph?”

“Because it’s the real person,” Lizbett said. “Not something fake. And it’s you know … full.”

“That’s right. It’s three-dimensional. So is a sculpture, but, as Lizbett says, this is the real thing, not an interpretation. When we put on a mask, we put on another face, a second face. And that mask blocks out the face people know us by and puts in another. But a death mask does not hide, it reveals, it records. So that’s our next mask, only it’s going to be a life mask. We’re going to put wet plaster gauze over our faces. If you’ve ever had a broken bone, you’ve seen a doctor mould it on your arm or leg. We’re going to mould it to the shapes of our faces, our noses, cheekbones, lips, chin, and so on and let it harden. And very carefully remove it. And there you will have an exact you. It will be more than a likeness of you. It will be you because when you remove the plaster, you remove something of yourself.”

“How long will it take?” Teddy asked.

“It takes fifteen or twenty minutes to make the mask, to prepare the face, then wrap the wet plaster gauze all over the face and smooth it into shape. And then it takes about twenty minutes to dry. That’s a long time to sit still, I know. If there’s anyone who feels uncomfortable about doing it, they can make a self-portrait mask out of clay. Is there anyone who doesn’t want to do it? We don’t cover the nostrils so you can breathe.”

Lizbett said, “Do we have to have our eyes covered? I really don’t like my eyes being covered. I hate blindfolds. I’ve hated them ever since I was little and we played ‘Pin the Tail on the Donkey.’”

“Of course, leave the eyes open if you wish. Afterwards, you can fill them in, the way the Egyptians did, and paint them if you choose. Now, let’s see, we’re how many? Twelve? Pick a partner and decide who gets the mask on first. Then you’ll trade.”

Lizbett and Carla paired up. And Teddy and Laurie, and Jesse and another boy. The rest found partners except for one girl, Kristin, who didn’t want to do it. Melvyn will do the mask on the odd person out as a demonstration.

Lizbett and Carla decided Carla will have the mask put on her that morning and then Carla will do Lizbett in the afternoon.

Coming back from lunch, Lizbett is a little apprehensive about having the plaster covering her whole face. This morning while she was smoothing the plaster gauze onto Carla’s face, Melvyn had asked them to think about the geography of the face. “Remember how we said a mask was a map of the face. Well, the face itself is like terrain, with hills and valleys and crevasses and gullies. Feel all that, not only as you apply the plaster, but as you are having it applied. Imagine your face as a landscape and what that landscape reveals.”

At lunch, the three who had had the plaster smoothed on them had mixed opinions about how it felt. One said it was warm. Another said it was squishy and weird. The third said it was sort of scary. All agreed it was a long time to stay still and that was boring but then seeing yourself in plaster was so neat!

Lizbett sits in a chair and lays her head back on a small pad on the table. She has tucked her mass of curls into the plastic bag and sealed it with Vaseline. And Carla has also carefully put it on her eyebrows and lips. She will leave the eyes opened, as planned. Melvyn has put on some soothing music … men singing in a low, chanting way. He says they are monks and the music is called Gregorian chants. Lizbett likes it, but her heart is still thudding a bit. How will it feel to have her face all covered for such a long time? Carla covers Lizbett’s face with flannel and then begins to apply strips of the wet gauze which warm as they sit on her face. But the gauze falls off and gets tangled.

Melvyn says, “Here, Carla, let me help.” Melvyn gently lays the gauze all over Lizbett’s face. She can feel Melvyn’s careful pressure as he smooths his fingertips across her forehead, over her eyebrows, across her cheeks and down both sides of her nose. With one finger he meticulously follows the contours of her lips and the groove of her chin and then tucks the gauze under it. The sensation is as pleasurable as having her hair washed at the hairdresser, but Lizbett is aware of something unsettling, something more personal. Melvyn is not the hairwasher. He is familiar to her. She realizes she has never been touched with such tender care by a grown-up other than her parents.

“Good girl,” says Melvyn. “Great stillness. You’re done, Lizbett. Are you comfortable? You have about twenty minutes to wait. You’ll feel the plaster begin to harden. Sit up if you want to.”

But Lizbett keeps her head back. She has been feeling a bit sleepy with the face massage. Melvyn was very gentle. She thinks again of the fact that all through the history of masks, they were only worn by men. Lizbett read that the Greeks believed that since men’s private parts were external, they belonged to the outer world and since women’s were internal, they were meant to live inside. And because of childbearing, women were considered closer to nature and needed to be controlled. Men would never allow them to go on display. They themselves played the women. Men wore women’s masks to be them, to create them as they wanted them to look and behave. And as women, men could act in ways real women were not allowed. They could break the rules they made for women. Some mask ceremonies were aggressive and violent. Women weren’t considered powerful enough to be in them. Men also used masks to make fun of women, to belittle them. All of this makes Lizbett angry and she has discussed it with her mother. Why did men treat women so horribly?

“Some men still do,” Meredith said. “They still keep them in a kind of prison. They don’t let them have their say. They don’t let them do the things they think only men can do. The think women are inferior. They treat them not as people, but as objects, mostly to do with sex. Do you understand what that means?”

“I think it means men think women aren’t really people, that they should be sexy, but not smart. Or not the boss, maybe.”

“That’s sort of it. Some men believe that women are weaker and dumber than they are and they keep them from moving forward. And men still hurt women in terrible ways.”

“But why? When it isn’t true? Women aren’t weaker and dumber. Why do they believe it?”

Meredith said, “I have a theory … it’s not entirely mine, but it comes from what I’ve read. Thousands and thousands of years ago, when humans were still very primitive, men were in awe of women because they could do two magical, powerful things men couldn’t. They could become two people … when they had babies. And they could bleed for several days … when they had their periods … without dying. When men bled for that long from an injury, they died. People had sex, but they didn’t know sex made babies or that bleeding had to do with that.”

“But then men became farmers, not hunters. And they started to breed animals and gradually they made the connection between sex and reproduction. If I do this to a woman, then she will have another person. So she needs me to do that. And when she has another person, she is weak and not able to get food. So she needs me to protect and provide for her. But how could a man be sure that a woman wasn’t doing ‘the thing’ with another man, as well? And how could he tell if the new person came from him or someone else? A man would want to know the new person came from him so he could give him some of his farm land and share his animals. He wouldn’t want to do that with someone else’s new person. And he didn’t trust that his woman would be faithful to him. Men saw women as temptresses, out to weaken men through their sexiness. So the man said to his woman, ‘If you want me to help and protect you, you have to stay inside and only see other women. You may never see another man except a father or a brother.’ That’s very simple, I know. But it explains to me why men have kept women down and confined. They have had to be sure their son was their son.”

“But what about modern times?”

“I think over the centuries it became such a standard for male and female behaviour that even as humans became more sophisticated, they were still wary of women’s sexuality, seeing it as something evil and disempowering. And they still believed women were weak and needed protecting and controlling.”

As she continues to wait for the plaster to harden, Lizbett imagines a play she is going to write where all the actors are female and all wear masks, male and female. And each character would wear two or three or even four masks, all representing different people … even though, in the play, they’d actually be just one person playing several different personalities and no one would ever know who anyone really was and one mask-person would know stuff about another mask-person and the person wouldn’t be aware of it. It would be a huge mix-up of identities. And people would get all confused and all sorts of things would go wrong. Maybe it could be another world or another species or hundreds of years from now. It would be like a crazy fairy tale, but not for kids, really. She is thinking she will suggest it at drama camp next month.

Melvyn cannot believe that on this day of all days, he has been the one to form Lizbett’s life mask, to stroke his fingers over her delicate, lovely face and create the face that would be her, that was her, an essential part of her. The thrill was almost more than he could bear and afterwards he felt unsteady. Her face, the external path to her, had been born in his hands.

He pulls himself out of his reverie and suddenly says, “Okay, Lizbett. Time to look at the real you.” Lizbett sits up, excited. And he loosens the edges all around her face and slowly, slowly lifts the mask off. When Lizbett looks at it, she says, “I didn’t know I had such a big nose! Or such a pointy chin.”

“You don’t,” Melvyn says, laughing. “It’s only that what you’re seeing is not what you see in the mirror, which is reversed and then interpreted by you, by how you hold your head, by what light you look at yourself in, by what you want to see. What you’re seeing in the mask is exactly how you are.”

Melvyn cannot believe how exquisite she is; how serene, how austere, how enigmatic. She is Lizbett, but she is not. What he is regretting is that Lizbett won’t be around to charge her mask at the end of the week, make her own “self” live. This has always proven to be a fascinating psychological exercise and most children, wearing their own life mask, lose all shyness and reveal selves that have never been otherwise evident. A lot of anger comes out, in boys especially. But the girls, too, become more verbally aggressive, their body language more forceful. Since Lizbett seems to be so constantly self-revealing, he wonders what inner spirit would have enlivened her mask.

But it is too late for regrets. His plans are set for this afternoon. He is desperate to carry them out.

Near the end of the class he gives Lizbett permission to leave a bit early. She wants to call her mother. But promptly at four, he dismisses the class and goes out to get his car. What luck. Pete is asleep. But as Melvyn clicks the door open, his heart stops. Pete suddenly sits up, his wide eyes seemingly staring at Melvyn. Then, just as suddenly, he falls back with a snort, his head dropping again to his chest. And Melvyn rushes away.

Pete will later swear that the door was never used on his watch.

After talking to her mother, Lizbett comes out of the museum doors at a little after four and stops to chat with several of her classmates at the top of the stairs. Big raindrops are falling. All the kids but Lizbett rush down to waiting cars. At the bottom of the steps, one mother asks Lizbett if she wants a ride. Lizbett indicates her umbrella and says, “No thank you.”

The umbrella is green with little frogs at the end of the spines. She puts it up. It’s a good thing she brought it because by the time she reaches the corner, there is a great flash of lightning, a violent, prolonged clap of thunder, and the sky opens. The rain that falls is dense and hard. A fierce wind closes everyone and everything in, in silvery, wet sheets. People are scurrying every which way to find shelter. Water flows over the sidewalks and rivers rush along the curbs. Lightning sears the sky again; a crack of thunder immediately follows. Lizbett stands at the corner, hesitating. She can barely see across the road. She wonders if she should simply dash into the hotel that’s on the opposite side. While she hesitates, a car pulls up making a huge splash and the passenger door opens. Lizbett hears, “Get in. Hurry!”

Lizbett bends down and sees Melvyn and quickly, gratefully, slides into the car, closing her dripping umbrella after she’s in. He pulls away practically as she’s doing it. In the confusion and power of the storm, no one has noticed a little girl with a green frog umbrella get into a grey Honda.

“Had to get out of there,” Melvyn says. “There was a bus on my tail. Look at you. Lucky I came along.”

“Lucky you did. I was getting soaked. I didn’t know where to go.” The car is cold from the air conditioning and she shivers a little.

“I was just passing when I saw you. How about that? So where to?”

“The library, I guess.”

The “I guess” makes Melvyn’s heart leap. He sees it as an opening.

“Why don’t we drive down to the pier and watch the storm? The waves will be fantastic.”

Lizbett doesn’t really want to do that, but she doesn’t want to hurt his feelings. He is very nice to give her a ride. She says again, “I’m going to the library to get some books on masks.”

“I’ll drop you there. C’mon,” he says. “It will be an adventure.”

An adventure. Melvyn is always saying, “Wearing a mask is an adventure. Always keep yourself open to adventure.” Her mother says, “Life should be full of adventures.” Besides, it’s Melvyn. She’s seen him all day, every day for two weeks. He works at the museum. She likes him even if it does feel strange to be alone in his car and go to the beach. She says, “Okay.”

“This could be a sort of date,” Melvyn says and reaches over and pats her shoulder. Lizbett has never been on a date, nor really ever imagined what one would be like, but she doesn’t think kids go on dates with their teachers, even ones as nice and friendly as Melvyn. She shrugs.

The pier, a couple of miles southeast of where they are, is in front of an abandoned nineteenth-century knitting mill. The pier extends far out into the lake. Cars can drive out onto it. Since it is so isolated, it is popular with teenagers. Lizbett has been walking there with her parents.

On the way, she chats easily with Melvyn, about making the life mask and how fantastic it was. She also tells him her idea for a mask play. She says how terrible she thinks it is that women weren’t allowed to wear masks.

Melvyn says, “Well, women were supposed to be quiet and invisible. Besides, men didn’t think women were clever or assertive enough to take on the powers of a mask. Masks were a connection to something beyond women’s understanding. Good women didn’t know about magic.”

“But the men wore masks that were women. Women who got them in touch with spirits or who were spirits. Didn’t that show that women were important? That they had powers?”

“The masks showed women as men wanted them to be, not how they were. It was a kind of control. ‘We say how you should look and behave. Or we’ll make you behave in ways we forbid you to behave.’ And you know, they thought women’s bodily functions … the way their bodies worked … made them part of nature and nature was something that needed taming or it would take you over.”

“It wasn’t fair,” says Lizbett. “Men had all the fun.”

“Masks weren’t really about fun. But look in the back,” says Melvyn. The two masks he’d chosen that morning were there: masks created from his face, a male and a female. The female was modelled after a Guatemalan maiden’s ecstasy mask, meant to represent the wearer’s sublime connection to the Divine during mock sacrifices. The male, derived from a Sri Lankan mask, was the lofty lord of the harvest, the supreme overseer, the guarantor of productivity. It was a maniacal face with black-lined eyes, bushy fur eyebrows, and a broad fur mustache that curled at the ends. The mouth was agape in a huge laugh.

“Wow! They’re amazing.”

“Put one on.”

“Really?”

“Sure. Why not? Put on the maiden’s mask.”

“That’s not the one I would have picked,” Lizbett says.

She turns around and picks up the mask and ties it to her face. It is quite heavy.

“Look at yourself in the mirror under the visor.”

Lizbett pulls it down and stares at the face before her, a beautiful white-faced woman with fur eyelashes and full, bright red lips surrounding a mouth that is open in a poignant cry.

“Make the sound,” he says.

Lizbett is startled at the gruff sound in his voice and asks, “What sound?”

“The sound she’s making. That’s how you’ll make the mask come alive; how you’ll feel something.”

Lizbett is feeling very uncomfortable now and says, “I don’t know what sound,” and starts to take the mask off.

“Leave it on,” Melvyn orders.

“I don’t want to.”

“Leave it on!” he yells. But she yanks it off.

There are several cars at the pier and Melvyn drives in well behind the mill. Lizbett now realizes something is not right and asks to go home.

“In a minute, sweetie,” he says. “We have something to do first.” He reaches over into his glove compartment and pulls out latex gloves and puts them on and then gets a roll of duct tape and Lizbett sees all this and reacts instinctively. She opens her mouth and places her teeth on his bare upper arm and bites down as hard as she can, grinding her teeth back and forth.

He tries to pull her off and she clenches harder. He is yelling and knocks her hard on the head with his free hand and she lets go, but she pulls at his hair and starts screaming. In vain. With the wind and the pounding of the waves, no one could possibly hear her. Plus they are all sealed in their own cars.

Melvyn quickly rips off a piece of the duct tape with his teeth and without even thinking he should wipe his blood off her teeth and lips, grabs Lizbett’s chin and holds the tape across her mouth. She is flailing and kicking at him, pulling at his face, his lips. He hadn’t expected her to be a fighter and he’s anxious and angry. This is not his Lizbett, his “Annie,” this monster child.

He slaps her across her face. “Stay still or I’ll kill you!”

She does. He tears off another piece of tape, slips her little purse over her shoulder and grabs her arms and twists them around her back and tapes her hands. Then he tightly tapes her ankles. Her widened eyes are flitting with terror and filled with tears. He cannot stand that and he suddenly remembers her saying she hated blindfolds and he tears off another piece of tape and puts it across her eyes. Now, there is only whimpering, which he also doesn’t like. It reduces her.

He picks up the maiden mask and places it over her face and ties it tightly. Then he puts on the male mask and checks himself in the mirror. He raises his chest, then inhales deeply and exhales making a long, low, forceful roar.

It has stopped raining and he gets out of the car, goes around and opens the door, and picks Lizbett up and carries her with difficulty, as she is thrashing furiously, into one of the side sheds which has a door slightly ajar. He pushes the door and they go in. There is an old mattress at the far end and he goes to it and lays her there. She kicks hard with both feet.

“I’ll kill you, I said. Kick me again and you’re dead!” he says. He peels off the tape from her ankles. He feels panicky now because of his fear of being discovered. He imagines lots of vagrants come here in the summer. Blood is running down his arm from the wound. A couple of drops fall to the mattress. So he moves quickly. He pulls off her panties and shorts, unzips himself, and shaking, puts on a lubricated condom, leans down, pulls her legs apart and penetrates her vagina, feeling it rupture.

This is right! This is what she is for. He is the supreme lord. He is the mask; the mask is him. His persona is primal, all his power, his inhibitions are released. He is part of a sacrifice of the most beautiful. She is before him: a trade-off, innocence and purity for an expunging of excesses. He wishes he had not taped her eyes so he could see her mask live.

But it’s never as he has imagined it. He’s imagined her co-operative, ecstatic. Lizbett stiffens suddenly and then goes limp. Good. She’s fainted. He puts his hands around her neck and tightens until his hands ache. There’ll be no resistance now. He concentrates on the mask, the now beatific mask, whose wail he can hear and pushes into her rectum and finishes. He has kept her from inevitable taint.

Now he has to get out of here. He takes off the condom and sees that it is bloody. He pulls on his pants and finds an old McDonald’s bag nearby and he gets it and drops the condom in. Later he will put the gloves in too and deposit the bag in a trash bin downtown. He doesn’t want to leave the body in the same place as the act. He looks out and sees the rain is a soft drizzle. He picks Lizbett up and notices a bloodstain where she’d lain. So what? The mattress is covered in stains, some of them probably blood. He picks up her panties and shorts and the McDonald’s bag and carries her a short distance away to a sluggish industrial canal, fuller than usual because of the rain. He considers dropping her in the water like the Mayan maidens who were thrown into the cenotes. But he decides not to. He feels a pang of something like sympathy, as if immersing her in a stagnant pool would somehow degrade her. And he decides it would be better, anyway, if her body were discovered soon. So he lays Lizbett face-down on a stray clump of Queen Anne’s Lace growing out of a piece of broken concrete. He has to undo the duct tape on her wrists to get off the red striped T-shirt, but he wants it. He takes the mask and hurries back to his car, unobserved, folding her clothing and putting everything on the seat beside him with her purse. Only then does he remove his own mask and before he drives off, he tosses the umbrella in the water.