Читать книгу No Worst, There Is None - Eve McBride - Страница 9

2

ОглавлениеThe Same Monday Morning in July 1986

The Warnes

The first thing she notices is the sky. It is lavishly streaked with crimson, a molten sun in the middle. A pulsating, bleeding sky. It feels violent, ominous, a harbinger of disaster. “Red sky in the morning; sailor take warning …” Meredith sighs. More storms.

Their house is on a street that climbs one of the steepest hills in the city and from her third-floor bedroom she can see out over the abundant trees (it is a city known for its green), to the office towers of the downtown and beyond that, a sliver of the great lake it sits on. She turns to look at her husband, Thompson, or Sonny, as he is occasionally called, a childhood nickname. He is sitting on the edge of the bed, his head in his hands, yawning. “Still not awake?” she laughs. She goes over and ruffles his fine, dark hair. He is a long, lean man, but soft, untoned with a little bulge above his pantline. Both of them are naked, having just made love.

It was hurried, more sensation than passion. She had, as usual, awakened early. Only this morning, lying there, instead of trying to return to sleep, she had curled herself around Thompson’s back and reached over and cupped his soft genitals. He groaned; didn’t respond. Mornings were his low point, the first few moments at waking grim.

“What do you think?” she asked. “Up for it?”

“Not sure,” he answered, not opening his eyes, not moving.

“Want me to try?”

“If you want. Some people like necrophilia.”

She laughed and pulled him over and lowered her head to his groin. This was as much for her as it was for him. She loved doing this, even with his disinterest. She loved his penis, ready or not. She loved the transformation from squishy, helpless thing in its nest of hair to solid, satiny tower. She loved to run her tongue around the precise rim of the glans, immerse the strong shaft into the wet warmth of her mouth. She felt power and pleasure with the possession of him.

His reaction, or its, was as she had expected and she reached into the drawer of the bedside table for the tube of K-Y jelly and lubricated them both and then she sat astride him and slid onto him. He still hadn’t opened his eyes.

“You know I hate this,” he said, with a sleepy grin.

“That’s okay,” she said, with a laugh. “It’s for me. It will soon be over.” And it was, she having reached orgasm by touching herself while she was on him, he quickly following her. She always loved sex, even when it was hurried like this. She loved its raw upheaval, the thrill of its temporary exposure. She lay on his lanky body, her own roundness filling his angles while he stroked her back.

“I do love you, you know.”

“Terrific,” he said, motioning for her to get off. They were both sweaty, more from the humidity than the exertion and she wasn’t a lingerer, in any case.

“Okay,” she said, sliding off him. “Up and at ’em. Time to get a wiggle on. No dilly-dallying,” which is what she says almost every day.

She heads for the bathroom and looks guiltily at the stationary bicycle in the corner. Her nemesis. Her struggle. Her weight. Tomorrow.

Thompson falls back onto the bed and puts the pillow over his head. In the shower, she lathers her curly, coppery hair and pale freckled body. She is beautiful, but not in the ordinary sense. She is more striking, with round, wide eyes, a small nose with a tilt, and a full mouth. Her face is always animated; her expressions pliant.

She thinks of the reliability of their sex, that it is not so much ardent (not after almost fourteen years of marriage), as loving and easy. Familiar. It isn’t boring or perfunctory. She doesn’t think that. What she feels is a small gladness for the surety of it; that Thompson would always be available and willing for it to happen.

She wonders if the girls have heard them. Not that they made much noise. She, a little, when she came, maybe, a stifled gasp. Besides they are on the spacious, remade third floor of their Victorian house. It has a large bedroom with a fireplace and bathroom and an office for both of them for their business, Artful Sustenance. He is a photographer, she a food stylist, and they’ve worked together successfully for six years since Meredith returned to work when Darcy was a year old. Before that, she was in advertising. Thompson has always been a sought-after photographer.

Lizbett, who is eleven, and Darcy, seven, are on the second floor, each in their own bedroom with a shared bath. There are two other bedrooms and another bathroom on the same level for guests.

Still, Meredith is always concerned about having sex when the girls are up. It’s better to wait until they are asleep. Thompson prefers that. Inventive, prolonged sex at bedtime. But Meredith is usually tired at night and not up to Thompson’s desires. Their best times are afternoons, with a bottle of white wine, when the girls are away or if they can escape somewhere for a weekend or a holiday, but none of these happens as often as they would like. So they compromise, taking turns with each other’s preferences and it has worked.

Or at least it is starting to again. Meredith is recovering from a recent six-month affair with a young mystery novelist, a swaggery extrovert who nonplussed her with his overtures and eventually she succumbed. And eventually she was hurt. He was probably a little in love with her, and she more than a little with him, but he wanted marriage and children and even if she were to divorce Thompson, she has had her tubes tied. Besides, she is forty. And she has Lizbett and Darcy, her beloved girls for whom she would do anything, even stay in a marriage that has felt less than full. But she still feels aftershocks from the affair, which was vigorous and inventive.

She had not thought she was unhappy, but she realized after being with Allan, who was a vital, spontaneous man, that Thompson’s quiet reticence, his understated responses, if he responded to her at all, have created in her a kind of hunger. Thompson is slow-paced, laconic. Allan was spirited, responsive, both loquacious and an enthusiastic listener. When she talked, he talked back.

Once she said, “I’m not sure why I’m doing this terrible thing.”

“Terrible thing?”

“This … being with you. I’m forty years old, married with two children I love … a husband I love.”

“Why are you, then?”

“Because you came after me. I was flattered. And intrigued. And it’s an added dimension to my life. It’s like parentheses filled with ignition and pleasure. Everything in my life has always felt so exposed. It just spills over onto everything. I like the secrecy of this … there’s a precariousness that’s sustaining … like being abandoned somewhere unknown. I don’t know what’s going to happen. But that’s the thrill. The unexpected. The dangerous.”

“Dangerous?”

“Well, in the sense that I am very vulnerable. I rarely feel vulnerable. I mostly feel safe. I organize my life so that it is. No surprises.”

“So this is not about me? It’s about the risk.”

“You’re inseparable from it. You invite defiance. You’re cocky and assured. You strut.”

“Strut! Jesus!”

“Yes. As if you have no match.”

“Maybe you’re just bad.” He’d laughed. She hadn’t.

“I hope I don’t get punished.”

Mostly the affair had puzzled her because she and Thompson had regular sex. Good sex. Sex wasn’t the issue. Nor was connectedness. They thought alike. It was really Meredith’s need for reaction.

Meredith is an extrovert, a demanding one. Some might call her brash. And her spiritedness needs fuel. When Thompson fell in love with that vivacity, he suspected it might come at a price. She’d offset his emotional timidity with an impetuous, almost ravenous devotion. But when she went after him, though he responded willingly, he did so with deliberate caution, fearing he’d lose something crucial. He lives within himself and does not emerge easily. He is an awkward connector. He doesn’t talk because he doesn’t like talking, so he rarely does, unless he has something important to say. Meredith was attracted to this quiescence, believing it to be depth, which it was. He was always preoccupied with the contortions and convolutions of existence; how greed and power superseded charity, how influence superseded compassion. He believed humans were primal, that “power over” was the engine of society and that manners and morals, intellectual and philosophical thought, art and music, were attributes of comfort and leisure without which instinct ruled. He was troubled by the fact that connection, the key to life was arduous and tenuous. Life was more about irony and survival than love.

Except where his daughters were concerned. For them he felt a feeling so pure, so clear he could almost see it — as a bright, overwhelming light, all-encompassing, inescapable, which began and stopped with them. They took up all of his deepest vision, the vision that fed his quiddity.

Even though she had always craved, commanded attention, it was a relief for Meredith to be with Thompson. His need for isolation was so embedded that it read like assurance, an independence that was appealing. But lately the restraint she had so admired in him had come to seem like indifference. She adored him, adores him, and she is certain he adores her, but she wishes it were not so complicated, that it did not require such effort to get him to acknowledge her. Sometimes she feels like screaming to get him to interact, to react.

One of the things that redeems Thompson — because almost everyone who tries to talk to him has a difficult time — is his wry sense of humour. He is subtle, quick, and acute. This morning, after they had made love, he had cracked her up when he said, “What took you so long?”

Above all, he loves her for her abundance: abundance of love and generosity, compassion, abundance of spontaneity and spirit, abundance of creative energy. Above all, she loves him for his spareness, his thoughtful withholding. They have had an embedded mutuality. They are like a wooden matchstick. Neither part is useful until the match is struck.

Below, Lizbett has heard her parents’ lovemaking. Her bedroom is directly below theirs and their bed has a light squeak. She realizes they are not aware of this or they would do something about it. She is not the least disturbed. She has grown up with an openness toward sex, first, when she was little with Where Do I Come From? Now she has thoroughly read Our Bodies, Ourselves and The Joy of Sex with her best friends. She has felt that throb between her legs. She has not yet masturbated, but she has had “pretend” sex with her best friend. And she has kissed her best friend’s brother, who is fifteen. That was nice, arousing even. She looks forward to knowing what real sex feels like.

She has been awake and up for some time. Ever since she was a baby, she has not been a sleeper. Meredith found her difficult because she was never still; always into everything. Always questioning. She continues to be like that. This morning she has already showered and dressed, tying her still-wet hair, the exact red of her mother’s, in a ponytail, putting on her favourite red shorts with a red-striped T-shirt and leather sandals. Before she leaves her yellow-and-white room with the daisy wallpaper, she makes her canopied bed and though she doesn’t play with them anymore, rearranges all her dolls in her old bassinette with the eyelet skirt. She loves the dolls. But she will be twelve in a few months and is on an ambitious new track.

For a moment, she sits at the edge of her bed, as if contemplating her next move and idly runs her fingertips across her lips. She feels a tiny bit of ragged nail and bites it, then presses it and bites some more. She does this with all her fingers until one of them is bleeding.

Recently she had the lead in a month-long run of Annie at the Nathan S. Hirschenberg Arts Centre and it has given her a kind of celebrity. Not that she didn’t earn it. She has been studying voice and ballet at the Conservatory since she was nine and told her parents she wanted to be an actress. Before Annie she had already played Gretel in a new musical version of Hansel and Gretel at The Children’s Theatre Workshop. She has done two television commercials, one for cookies, the other for cereal. She will go to sleepover drama camp in August, as she had last year. She has been acting, really, from when she could walk and talk and realized her antics got a positive reaction. Anytime she has an opportunity to perform, she does. The part of Annie was hard won. Dozens of other girls auditioned. For Lizbett, the thrill of the exposure has only whetted her appetite for more.

She has no illusions, however. She is astute and practical. She knows life doesn’t always go as she’d wish. And she feels divided in courting her parents’ pleasure and finding her own way.

Lizbett feels especially attached to her mother. They have a special “oneness”; their ways of being are in tune. Not that Lizbett isn’t aware her mother is the adult and she is the child. Her mother can be firm and demanding and she sets boundaries. But she is loose and loud and showy and Lizbett loves how she attracts attention. And Lizbett knows she and her mother think alike, have the same aspirations. She knows her mother is ambitious for her. She is ambitious for herself and she likes having an ally. Ever since she was very little she and her mother have chatted easily and laughed, exchanged feelings and ideas. Lizbett shares all her plans and misgivings with her. They have walked together, shopped together, gone to art galleries and films and the theatre together, cooked together, watched TV together. Before Lizbett was in school all day they even “lunched” together at spiffy restaurants. Though she knows it’s maybe inappropriate, she likes to think of her mother as her best friend.

With her father, her relationship is more confined. She does not find him easy to talk to, but he is more affectionate than her mother. He is always available for a tight hug. And until recently, she could climb on his lap and snuggle into him with his arms around her and stay for an indefineable time. He was fun and funny. They used to have a silly game. They’d play it over and over. She never got tired of it.

He would ask, “Lizbett, what’s the difference between a duck?”

“Oh, Daddy, that doesn’t make sense.”

“Then what’s the difference between a duck and a train?”

Lizbett would laugh harder. “That’s ’dicilous,” she’d say.

“Okay, then. What’s the difference between a duck and cheesecake?”

As the comparisons got more and more absurd … “What’s the difference between a duck and a dinosaur, a sofa, a hamburger with ketchup?” Lizbett would be shrieking and giggling uncontrollably.

She loved their reading and playing the piano together. They just didn’t talk much.

In her acting, Lizbett has the ability to enter the character she is playing, slip into her skin and become her. Take on her identity. At the same time as she does this, she also animates the character with her own sensibilities and vitality. The two meld. For this she is praised: for her naturalistic, un-self-conscious portrayals.

Meredith volunteers every second Saturday morning at a settlement house that provides daycare for single mothers. Most of them are teenagers who go off and do teenage things while their small children are looked after. Lizbett sometimes goes and helps out and the thing that most overwhelms her is not how shabby and unclean — even a bit smelly — the children are, but how passive. Their only stimulation has been the television, which they’ve been plopped in front of from their earliest months. No one has read to them, played hand and face games with them, coloured and drawn with them, performed puppet shows for them. Lizbett does all this with pleasure, but she feels, sadly and with some early cynicism, that it means very little. It bothers her to return to her privileged life when the children have to return to their deprived ones. She doesn’t know how to reconcile the imbalance.

Down in the kitchen, she pours herself a glass of milk, then goes into the family room, sits at the piano, and begins to practise. First she does some hand stretches and then she begins the scales, then the arpeggios. She brings out a book of exercises and plays each one, diligently, though not effortlessly. She is a good pianist, but she is a careless one, going through the pieces the same way she goes through life, with enthusiasm and endurance, but not necessarily focus, concentration. Her head is in too many places at once.

She begins a Schubert piece she has been working on for some time.

Upstairs, lying in bed, a Huey Lewis song is running through Thompson’s head. “Doin’ It All for My Baby.” He really doesn’t like sex in the morning. He feels groggy, subpar, as if all his neurons aren’t firing. He doesn’t like the bad taste in his mouth and he doesn’t like the smell of Meredith’s. He doesn’t like that his body feels stale, raunchy. But he is particularly aware right now of Meredith’s need for responsiveness and this morning was the best he could do. He knows she has been having an affair or rather he keenly suspects something extraordinary has been going on. Her euphoria, her frequent absences with odd explanations, her heightened attentiveness to family, her increased sex drive, her more than usual garrulousness all suggest this. He was once the object of such excess. Not that Meredith isn’t always a bit excessive, but in love she’s almost manic.

That’s how it seemed when they were in university. She was an exchange student from Australia doing her junior year in Fine Arts as a painting major. He was majoring in photography. They had a seminar together, “Food in the Paintings of the Baroque Era,” which they both loved.

He wasn’t sure exactly what he had done to attract her. He was handsome in an unassuming, untidy way, but he wouldn’t have thought so. He had an ungroomed beard and his dark eyes under heavy eyebrows gave him a gruff look.

He was not used to female attention, having gone to an all-male boarding school from age ten. And he was diffident, a late only child with parents so engrossed in one another that he felt he was a basically a distraction to them. His only contact with his mother — his father only came on weekends — was summers at their island cottage up north. Being alone with her in that isolated setting, in deep silent woods by active, glistening water, Thompson learned something about women … or his own intimate version. His mother exuded care, but she was removed and he would watch her move about the cottage, on their walks, while they swam, in awe, as if she were something “other,” a mystical being. She was elegant and gentle and convivial; she treated him not as a son, but as a companion. She never hugged him, but somehow seemed to embrace him in a respectful, solicitous way. She engaged him, seemed interested in his thoughts. What he felt from her was a kind of power, an intelligent, creative, thoughtful power that reinforced his life, but did not enter it. She was unknowable.

So Meredith’s initial undisguised ardor, especially her physical overtures, overwhelmed, but also pleased him. It seemed to require so little effort on his part.

“I’m not used to so much fuss,” he said.

“You just don’t know how to deal with …”

“With …?”

“Love.”

“It’s not anything I ever imagined having.”

She took over his life.

“I’m not sure what you see in me,” he said after a session of particularly fervid sex when Meredith was so loud he was afraid the upstairs tenants, a group of earnest student teachers, would hear.

“I’m not sure, either.”

“Is it because I’m so eloquent?”

She laughed. “No, you only speak when you have something to say …”

“Which isn’t often,” he interjected.

“Which isn’t often. Right. My father is a church minister who never stops talking. He preaches and proselytizes and lectures and tells the same stories over and over and we have to listen, my sister, my mother, and I. We weren’t allowed a voice. All he had to do to get us to shut up was give us a withering, destructive look.

“He was mean?” Thompson asked.

“Oh, no, never! He was … is a gentle, kind man, but he was a stern lecturer and so boring and repetitive. And from early on, I thought what he said was such bullshit! You have no bullshit in you. I … love how grounded you seem. I always feel as if my feet never hit firm ground … as if I’m … not flying … but moving just above the surface of things, never really in contact. I feel a little as if you pin me down.”

“It’s nothing I do,” he said. “Or mean to do.”

“I know. It’s me.”

“With your father the way he was, I mean, a silencer, how did you get to be such …”

“Such a yakker? From him! Once I was out of the house I couldn’t shut up. I think I must be full of bullshit. You haven’t noticed?”

“I’ve noticed!”

“And …?”

“It’s okay. It fills spaces I can’t or don’t want to. And I can tune out.”

“I’ve noticed.”

“Sorry,” he said.

“I don’t mind.” she replied. “Because it means the pressure’s off me.”

“What pressure?”

“The pressure to keep you amused so you’ll want to be with me.”

“I want to be with you.”

“You do?”

“Yes.”

“That’s the first time you’ve ever said anything.”

“Well, you’ve never wanted to know.”

He senses now that she wants to know. She’s gone into retreat mode which is rare for her. Retreat mode for Meredith means she is distracted, distanced. She doesn’t talk. She goes to bed. The girls put their mouths to her ear and say, “Earth to Mom!”

He is thinking he should be jealous. That would be the reasonable — or unreasonable and instinctive — way to feel. Perhaps he should be enraged. But he just feels sad: sad at his own passivity, that in some way he has failed her, failed her enough that she has heaped her affection — that’s how he sees it — on someone else. Her affection is a loose, lavish, limitless weight. It is not in his nature to ask her what’s wrong. If something is wrong, she’ll tell him. Or so he believes. Either that or he’ll lose her. He feels that actually preventing that is beyond his power. He can only keep loving her as he always has, steadfastly, profoundly, heedfully, and hope it’s enough.

Lizbett enters the kitchen where Meredith is studying a shopping list. She and Thompson have a big contract: a five-page Christmas editorial for RARITY. She says to Lizbett, “Lovely playing, darling.”

“Thanks, Mom. It’s Schubert. It’s really hard.”

“‘The Impromptu Number two in A Flat,’” says Thompson. He is making a pile of toast and peanut butter for the table while he puts together the girls’ lunches. “It sure was hard.”

“Nan-Nan is always telling me how you never practised. How she doesn’t want us to end up like you.”

“I wish I had now.”

“I like your jazzy stuff.”

He leaves the lunch-making and goes into the next room with the piano and plays few vibrant riffs from Ray Bryant.

Meredith looks up. “Sonny! C’mon! Has anybody seen Darce? Isn’t she up yet? Lizbett, go upstairs, please, and get your sleepyhead sister out of bed.”

“Why is she so bad? Do I have to?”

“I already stuck my head in,” says Thompson.

“So did I,” says Meredith.

Lizbett enters her sister’s ocean-blue room with the red plaid curtains and opens them.

“Don’t!” yells Darcy. She buries her dark head in the pillow. Dora, Meredith’s mother, is descended from the “Black Irish” and Darcy has inherited her colouring. When they are open, her eyes are a deep brown, with black lashes — unlike Lizbett’s, whose blond lashes fringe bright green eyes. And Lizbett is pale like her mother. Darcy’s skin is olive.

She is like a sprite. Her family likes to say she is “no bigger than a minute.”

“C’mon, Darce. Mom said. You’ll be late for camp.”

Darcy whimpers, “I don’t want to,” and Lizbett puts her hands under her sister’s back and lifts her into a sitting position. She flops back down.

“Please, Darce. C’mon, I’ll help you.” Reluctantly, Darcy pulls herself out of bed. She is a wistful child. Where Lizbett is impulsive, spontaneous, Darcy is pensive, hesitant, as if she regrets, not her short existence, but any disruption that may occur in the future. This has nothing to do with premonition and everything to do with her view of life, which is essentially sad. She was only three when their beloved Great Dane, Misty, died, but the sorrow that pervaded the house affected her deeply: seeing her mother, father, and sister weep openly. She clearly remembers the dog’s enormous bodily absence and the wonder of that. Now she fears separation of any kind, sensing it may be permanent. But she knows her parents, her mother especially, disapprove of any fuss, so she has developed a brave face. Getting up in the morning means she is going to have to put it on.

Lizbett leads her into the bathroom where she fills the sink with hot water, wets a washcloth, and washes Darcy’s face. Then she puts toothpaste on her toothbrush, says, “Open,” and brushes Darcy’s teeth.

Back in the bedroom, she pulls clean clothes out of the drawers, some panties, brown shorts, and a white T-shirt and helps Darcy put them on. By now, Darcy is awake and she bends over and buckles up her sandals.

“Let’s make the bed,” says Lizbett and together, one on each side of the bed, the sisters pull up the sheet and blue coverlet.

“Careful not to disturb Mr. Mushu and Geoffrey!” Mr. Mushu is their Siamese cat and Geoffrey is a stray tabby who arrived last winter during a snowstorm. The two beloved animals are curled up at the bottom of the bed cleaning each other.

“Darcy, honey, what are we going to do with you?” Meredith says when the girls arrive in the kitchen. “Stephen and his mommy are going to be here soon to pick you up. You barely have time to eat.”

“I can take some toast in the car. I’m an owl, like Daddy.” It’s true the two of them have trouble getting to sleep at night. Thompson reads in bed. Meredith has taken to allowing Darcy to do the same. Better to have her absorbed than tossing and turning. Books are her life, in any case. She often has two on the go. Meredith has tried to help her develop other activities, but Darcy has resisted. Apart from the piano lessons, which she also takes with her grandmother, she is not interested in anything else except the cats. And, unlike Lizbett, who has a group of close friends, Darcy only has Stephen, who has been her friend from nursery school. Meredith thinks this is far too passive a life for a child to lead. Her contribution to family life is being complaisant.

Maybe she is a late developer. She certainly was a late talker. While Lizbett had said words at ten months and full sentences by eighteen months, Darcy spoke few words, even at two years. Meredith keeps watching for an artistic bent to surface. Her artwork from school has shown promise. She is hoping that the art camp she is attending at the City Art Gallery will inspire her.

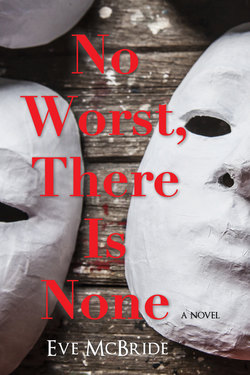

As Lizbett is leaving to walk to the Courtice Museum for her mask camp, Thompson hands over her lunch. “Thanks, Daddy,” she says. “Hope it’s good like yesterday.”

“Should be. It’s the same as yesterday.”

Meredith says, “Daddy and I are starting a new shoot, a big Christmas one for an important magazine. We’re going to be really, really busy for a while, at least the whole of this week.”

“Christmas in the summer?” Darcy asks.

“Crazy, isn’t it?” Meredith answers. “Just like Australia. But that’s how long it takes a magazine to prepare an article like this. Come straight home from mask camp, Lizbett. Brygida will be here and will get you dinner if we’re not home yet.”

Brygida Breischke is their Polish housekeeper who has been with them since Meredith went back to work and she is their lifeline. She keeps them corralled the way a border collie herds sheep, with an indomitable, tireless energy. As it is, she is inefficient and hurried, the kind of woman who runs through her work whacking the vacuum against baseboards and furniture and missing dirt and dust everywhere. She breaks a lot of dishes. In a day she can clean the house, do laundry, and iron shirts and pillowcases and still have time to make perogies or a veal-and-pepper stew. When the girls were little, she was doting, but firm, and took them to the park every morning. In the afternoons, they curled up on a sofa with her and watched soap operas. She thought they improved her English.

Her daughter Aniela often came to the Warnes’ with her mother during school holidays and Lizbett and Darcy love her. Meredith thinks of Aniela almost as a niece. When Aniela graduated from art school, the Warnes helped her to get a job at a gallery. Both Brygida and Aniela have spent nights at the Warnes’ to get away from Tadeusz, the husband and father, when he knocked them around.

Now Brygida only comes in the afternoons and stays to get Lizbett and Darcy’s dinner if Thompson and Meredith are late. But they don’t like her cooking. They find it greasy and mushy.

“I don’t have to eat here tonight,” Darcy says. I’m having supper at Stephen’s.”

“Oh, that’s right. I forgot.”

“And Mom. I wanted to go to the library to look at mask books. I told you.”

“There’s going to be a big storm, Lizbett. I think you should come right home.”

“Mom! The teacher told us to. I have to. Storms don’t matter. I always go to the library by myself.”

Lizbett is keen to please her teacher. She has engaged with Mr. Searle … Melvyn (he has told them they can call him Melvyn) … with Melvyn in a compelling way. She thinks about him a lot; finds him cute. His suggestions for her work flatter her. He is not like other teachers. He doesn’t have that grown-up distance. It’s not that he jokes or even fools around. He is simply kid-like, maybe because he is closer to their size, maybe because he has a young face. Maybe because he is right in there with them and seems to like them so much. She even thinks she might be his favourite and she likes that.

Thompson says, “Let her, Mer, if it’s so important to her. She’s a big girl. And the storm may not happen, anyway.”

Meredith acquiesces. The library is three subway stops north from the museum and Lizbett has made the trip many times. Maybe Thompson’s right. Maybe the rain will hold off. In any case, she’ll be mostly underground.

“All right, lovey, go. Now, off you go, lambies, or you’ll be late. Don’t dawdle. And Lizbett, take your umbrella.”

“I already have it,” she says, going out the door where Stephen and his mother are waiting for Darcy.