Читать книгу No Worst, There Is None - Eve McBride - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

1

ОглавлениеThree Days Earlier: A Monday Morning in July 1986

Melvyn Searle

The first thing he notices when he looks out the window of his second floor flat is the sky. Red. Glaring, voluptuous red. A crimson sun. “Red sky in the morning …” This may interfere with his plans. But the heavy rains will actually work in his favour.

Melvyn Searle’s flat is in a red brick house on a square of similar two-storey houses with broad verandahs, constructed just before the First World War. The square is leafy and the small front lawns, most of them with low fences, have well-tended gardens. In the centre of the square is a lovely little park called Schiller Park, because Germans were the early residents here. There is the ubiquitous wooden structure for children to play on.

Many children go there: younger ones in the morning with their mothers, but in the afternoons, when school is out, older children come, as well, and use the big set-up for their games. Sometimes even teenagers hang around. On Saturdays and Sundays, the park is filled.

Melvyn’s flat occupies the whole second floor. At the back, steep stairs lead to a driveway where he parks his grey Honda. It’s more space than he needs, as he is single, but he can afford it and he likes the area. And it’s only a short bus ride to the Courtice Museum, where he is head of the education department. He has an MA in ethnology. His specialty is masks. But he also earned a B.Ed. because he loves to work with children.

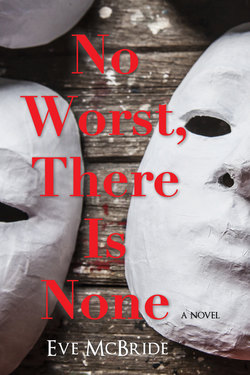

This morning he leaves his sparse bedroom with the dark furniture inherited from his parents and wanders in his striped pajama bottoms into his equally spare living room — except for the walls on which hang a great variety of masks. Besides those, the room contains only a couch and a chair. Above the couch are two inconsistencies: Arthur Rackham posters of Alice in Wonderland. On a side wall there is a shelving unit that holds a TV and a portable stereo on which he often plays children’s records. “Free to Be You and Me” is one of his favourites as are “The Frog Prince” and “Honey on Toast.”

The masks are impressive. He sometimes splurges on purchases, but his prized possession is a carved wooden Congolese kifwebe mask, whose intricately etched, angular shape gives it a Picasso-esque look. He also has a Chinese lion mask. And a glass mask from Poland. Most of his masks are copies he has made himself. An Indonesian Topeng Dalem mask. A Nigerian maiden spirit mask. A Hellenistic terra cotta mask. And several beautiful Japanese Noh masks, their simplicity, their apparent vacancy actually faces of restrained, secretive, exquisite revelation. Still others are his own creations, extensions of himself from a plaster mould of his own face. These are the masks he has used for his … what shall he call them? Escapades? Rituals? Rites? He wonders which ones he will choose for today.

His masks are an obsession. He loves their ironic duality: the wearer gives a mask life, but a mask also gives the wearer life, a wholly new life that sometimes comes deep from within and sometimes is external, something desired. A mask knows. A mask, though inanimate, has a subversive vitality. From the moment the wearer puts it on, a mask is born and finds its own voice. The mask overwhelms the wearer and the wearer injects that into mask. There is crucial intimacy between them. One cannot exist without the other. Without the wearer, a mask is simply a static aesthetic object. On him, he and the mask both come alive.

He leaves the masks for now, although still pondering his choices for today and goes into the kitchen. It is a former bedroom and is quite large, but has only one small counter with a sink, a narrow gas range, and a refrigerator that is covered with children’s drawings, gifts mostly from his Saturday-morning classes. There are also pictures of little girls from magazines and there is a newpaper photo of Lizbett Warne as “Annie.” A couple of Polaroids he took of his current mask class with Lizbett in them are up, as well. He also has a photo of her in one of the masks she has made, the star mask … as if she needed such an extension of her vivid self. The pictures of Lizbett give him a thrill every time he looks at them and imagines the time when they’ll be together. But today, as he opens the refrigerator to get himself some juice, he feels much more. He feels a frisson of apprehension, a flip in his gut, a stirring in his groin. This is the day.

He flicks on the radio. The war between Iran and Iraq is still raging. Iran is supporting the Kurdish guerillas fighting for autonomy in Iraq. A car bomb has killed thirty-two people in Beirut and wounded 140 others. The trade and budget deficits are worsening. The Chernobyl clean-up is an ongoing horror. President Botha has declared a state of emergency in South Africa where millions of blacks have been on strike to protest Apartheid.

Melvyn turns to a classical music station and gets a Mozart clarinet concerto. He switches it off. He is too keyed-up for music.

He is a pale, small man, very thin but with a disarming agility, a childlike looseness. His face is almost beautiful, with high, delineated cheekbones, a fine nose. His skin is smooth and taut. His limpid eyes, the colour of Wedgwood and defined by pale, thick lashes, are magnified by round tortoiseshell glasses that correct his far-sightedness. They give him a look of wide-eyed enthusiasm. And his hair is baby-soft and blond. No matter how he has it cut or what he puts on it, it is unruly, with cowlicks. His thin lips, when pulled back in a smile reveal small teeth with a space between the two front ones. If he were more mannish, he would be called handsome, but really, at age thirty-two, he is more boyishly appealing. This ingenuous physicality encourages connection. Children, especially, are drawn to him not because he is overtly affectionate but because he has a soft, highish voice. He inspires engagement and he exploits that.

He switches on the coffeemaker, which he has prepared the night before and decides to make scrambled eggs, which he does methodically, carefully cracking three eggs in a bowl so as not to get any shell. While the eggs are slowly cooking (he likes them soft), he butters whole wheat toast and then sits down at the wooden table with the carved legs and eats.

He thinks of Lizbett Warne. He knew of her, the way others did because of her role in Annie, but he never aspired to her. However, when she appeared at his mask camp, he was delighted. What unexpected serendipity. What fortuitous availability. All little girls appeal to Melvyn, but he aims for the ones who shine. That’s why Lizbett fascinates him. Her intelligent sparkle, her sweet-natured vivacity set her apart. Her luscious girlishness is magnetic. She is generous with herself, standing out because she wants to, though not in a pushy way. She seems to ease naturally and comfortably into showmanship and other kids look up to her. He wouldn’t say she is the brightest or the most insightful, but she is the most assertive. Where her fellow maskers seem reluctant to offer their ideas, Lizbett is full of them. He has worked on developing a rapport with her.

We have a relationship, he thinks, with a surge of confidence.

He cleans up the kitchen, meticulously drying each dish, utensil, and pot and putting them away in their proper places. He gives the floor a quick sweep and waters several pots of ivy on the windowsill. He goes into the bedroom and makes his bed, careful to smooth away all the wrinkles on the lavender coverlet.

Melvyn is not as preoccupied with his person as he is with his house. His clothes, mostly chinos and madras plaid shirts, short and long-sleeved, are clean and pressed because he takes them to the laundry, but he wears them longer than he should.

He does shave, closely. With a razor and a cake of shaving soap in a wooden bowl. He looks smooth-cheeked, but he actually has a blond beard which, if grown out, would be quite full. He dislikes his whiskers, sees them as detriments to his purpose (of appearing boyish), so every day he scrapes away the stiff hairs until his face is pink and shiny. His father, a captain who flew Lancasters during the Second World War, used to say, “a soldier always shaves, especially before a battle.” Melvyn wonders if he is a soldier, if what lies before today him is actually a kind of battle; an assertion of desire and of supremacy not over an enemy, because Lizbett is anything but an enemy, but over the unsuspecting, smug society that claims her.

Melvyn doesn’t shower. Once someone mentioned his body odour to him. Melvyn doesn’t shower because he doesn’t have one, but he does have an old-fashioned claw-footed bathtub. However, he hates to bathe even more.

This morning is one of those mornings when he feels he should have a bath. He tries to talk himself out of it, reminding himself he had bathed last week — was it Wednesday or Thursday? — but something pushes him and he runs the water until the tub is quite full, slips off his pajama bottoms, steps in, and slides back, immersing himself completely. In the hot surroundings he begins to remember, but it’s when he washes himself that the images flood back. He washes his genitals and backside quickly, perfunctorily, as if it were painful there. This is where his stepmother began. At bathtime. In his earliest recall, he is three or four, an intense little boy with a cap of white curls and an angelic face. His wide, round blue eyes are filled with tentative curiosity. Stacey soaps and massages his genitals, pulling and stroking the little penis continuously. And then she inserts one or two soapy fingers over and over, deep into his rectum. Or something big and hard. He squeezes his eyes tight so he won’t cry. “Good boy,” she coos. “Good, sweet boy.” He doesn’t know if he’s good or bad. He only knows that he doesn’t like what she is doing; that it makes him sore. She gives him hugs, but he is afraid of her.

As he gets older and begins to bathe on his own, she comes into his bed late at night when his father has passed out from Scotch. At first she just fondles him. But when he begins to experience erections she starts to put her mouth on him. Eventually, he is entering her. And then it stops, when he is in high school. She no longer comes into his room because she becomes pregnant. And everything in his life changes. Stacey calls the new baby Alice after her favourite book.

He never wonders how his stepmother could have done what she did. She may not know. Or then, again, she might. Her father, Marvin, was a dentist, the youngest of six children, with five older sisters who wandered in front of him naked, mothered and bullied him, teased and used him as a little houseboy. When he was little, they flicked at his penis. And his mother either dressed him in girl’s clothes or neglected him.

Marvin had three sons, and then Stacey, and though he doted on his little girl, as she got older he saw in her a personification of his sisters and that’s when his violations began, in a kind of erotic rage. She was the one whimpering and sore then. It continued until she left home in her late teens. If Stacey’s mother had any idea of her husband’s mistreatment of her daughter, she never let on. She had enough trouble dealing with his erratic meanness.

Sometimes Stacey’s mother would go to her sister’s with Stacey and it was there that Stacey discovered little bodies when she slept with her much younger cousins. They would cuddle up close to her in the bed. One night, three-year-old Cal woke up crying, and, to calm him, she caressed his genitals. She thought he seemed to like it.

In fact, Stacey had grown up believing sex was something males did to females, but because Melvyn was there and so passive, and perhaps thinking of little Cal, or in some kind of unconscious retaliation, she acted out against her stepson. Others tempted her, the little ones at the nursery school where she worked, for example. Sometimes when she took a boy to the bathroom, she would fondle his penis.

Melvyn’s thoughts of Stacey recede when he is out of the bath. She lives in another city. Alice ran away when she was fifteen. His father died of pancreatitis, aggravated by his alcoholism, just before Melvyn moved here. He thinks of himself as being without family.

Melvyn steps out of the tub, reaches for a towel, and dries himself. He reaches for the deodorant in the medicine cabinet. Then he goes into the bedroom and puts on clean chinos and a pink-and-green madras short-sleeved shirt. In the drawer where he keeps his shirts there are several little girls’ T-shirts, and on top, a pink sundress embellished with a cartoonish, sequined cat and words that say, “I’m A Pretty Kitty.” He looks at them and wonders what Lizbett is wearing that day. A dress, he hopes. A dress makes things much easier. Besides, dresses make little girls more appealing. He can imagine their sweet legs all the way up to their panties.

Melvyn Searle’s father, Ralph Searle, was a mid-level banker. He was a surly man and never sober once he got home from the bank at six. Melvyn tried to avoid him by staying in his room, but there was the dinner table where his father always seemed to find a reason to hurl insults at him or cuff him over the head. Once he dislocated Melvyn’s arm when he pulled at it. “Straighten up!” he’d yell. “Or speak up!” “Don’t chew like that!” “Clean your plate!” “You’re a freakish little twerp fuckhead, you know that?” “Get up and help Stacey, you lazy chicken’s asshole!”

Melvyn seems to think his father wasn’t always like this. He imagines that when his mother was with them, his father was nicer. But his mother left them when he was only two. He can picture being on her lap, nestling into her soft chest, but her face is a blank. And there are no photographs.

His father’s mother took over. She was like her son: never sober and always mean. His father brought Stacey home quite quickly and Melvyn’s grandmother left. At first, Stacey seemed nicer than his grandmother. She did everything to gain his trust, especially reading him all the stories she did. He couldn’t get enough of books. He loved the alternate worlds they offered him. Stacey was a wonderful, expressive reader, pulling Melvyn close in beside her, enveloping him with one arm. He felt so cozy and safe.

Being around children was the only time Stacey felt in control. When she was with them the insecurities, the shame, she felt around adults disappeared. And when she read to them, clustered all around her, her voice bringing them the power of the words, she felt assured and capable of love. And she loved to sing with them. Joy burst from her then.

Stacey first caught Ralph’s eye when he was looking at schools for Melvyn. He watched her for some time. He thought she would be good with Melvyn, who was a shy, clingy boy.

She was a very thin, pretty woman with thick blond curls, but she was edgy. Her eyes flitted and she slouched. Stacey was young, at least ten years younger than Ralph’s thirty-six and was slightly in awe of him, but also wary of him, looking up to him, but uncertain of his reactions. He was an overbearing man. She had rotten luck with men, especially the last one whose bullying escalated to hitting. She hoped Ralph would be different. He was handsome and could be affectionate, and he was older with a good, steady job and a young son. Melvyn grew up calling her Mom.

His favourite thing to do with her was make masks. She had a boxful of childish treasures: intriguing buttons, feathers, sequins, rhinestones and pearls, bright ribbon, silver and gold paper, raffia, myriad stickers, and, best of all, vibrant markers in many, many colours. She bought plain white masks, which he decorated lavishly. They cut holes in paper bags. He liked these because he could attach all kinds of hair from the Hallowe’en wigs Stacey found. Sometimes, if Stacey was in a mood to cope with the mess, he moulded a face out of papier mâché.

He loved putting on these masks and staring into a mirror. When he did this, he created an elaborate fantasy for the character he was portraying, a character far removed from himself. Like the red wizard with the ruby eyes and bright, full lips. He entered a world of power and magic whereby he could create new beings and make others vanish. The wizard had a mother, a shining queen in a pink and silver gown who smiled and sang instead of talking and caressed him and brought him gifts. When he put on his queen mask, he was beautiful.

He surrounded himself with other children who would do his bidding.

Ralph wanted Stacey to go back to work when Melvyn was in school, but she refused. She said she would need to upgrade her skills. So she sat in a big armchair reading all day long, smoking cigarettes. At first she only drank when Ralph got home, but then she began to pour something in the afternoon and by the time Melvyn got home from school, she was drunk.

Alice’s birth sobered Stacey up, at least for a couple of years. It was then that Melvyn discovered how the happy loving innocence of a baby, how her little arms about his neck made him feel whole. Stacey taught him essential baby care and he became a big help to her. When he changed Alice, he was fascinated by her bottom, its minute, intricate, perfect folds. He would probe the tiny vagina with a baby-oiled finger.

His favourite thing was dressing Alice in the pretty, lacy pink clothes Stacey bought for her. Sometimes he and his stepmother would take the baby for a walk in her carriage. Melvyn thought this was what a family must feel like. Sometimes he would imagine having a daughter of his own one day.

But by his senior year, Stacey had relapsed and he’d arrive at the house to find Alice asleep or crying in the playpen and he had to take over a lot of her care. He was working toward a scholarship to get into a nearby college and he resented having her on his hands. And Alice was entering the terrible twos. She was no longer a pliable, responsive doll, but a defiant, tantrum-throwing toddler with huge needs he felt incapable of filling. The only way he had any control over her was to read to her, all the books Stacey had read to him.

And bathing her at night, it seemed right that he repeat his stepmother’s acts. Everything about her body, pink from the hot water, seemed receptive. Except Alice wasn’t. She flailed and cried. Why hadn’t he? Maybe he had and he didn’t remember because it became so routine. He took to giving her Double Bubble or cherry lollipops to quiet her. Once Stacey came in and caught him and she punched and pounded and kicked him almost senseless, screaming at him that he was filthy and disgusting and a pervert. He stopped giving Alice baths, after that. But he didn’t stop wanting to do things to her, to her pale, smooth inviting little body. He found ways. Mostly he found he could sneak into Alice’s room after Stacey had passed out in bed, the way she had to him. By the time he was near to finishing college, he was penetrating Alice, calling her “Sweetie,” telling her she was his own “good, good little angel-girl.” And reading to her. And buying her sweet pink dresses.

On this now menacingly hot July morning, Melvyn exits his house, already feeling excited and impatient for what is ahead. He hasn’t questioned his motivation. What compels him is pure attraction, the enticing idea that Lizbett wants him. He is sure she does. Her girlishly scintillating reactions to his overtures have convinced him.

He has some time so he decides to sit in his park for a bit and watch the children, most of whom he knows and who know him. He feels this will calm him. He is always jumpy before one of his encounters. He plans them so carefully, but anything could go wrong. He’d phoned the Warnes yesterday and asked to talk to Lizbett, simply to make sure she’d be coming today, but she hadn’t been in. He didn’t identify himself. This will be Lizbett’s third Monday. Her routine doesn’t usually vary. She walks to the museum alone and then walks home. He feels pretty certain today will be the same.

He wonders if what he feels for Lizbett is love, if he knows what love is. Certainly, what he feels is powerful and he has the sensation she affects his heart. She does not make it beat faster; she makes it swell until it is painful. He wants to pound his chest for the pain. He longs to be with her, to take her in his arms. That’s it, really, he wants to overtake her, to incorporate her existence into his. Not obliterate her, but possess her with every fibre of his being. If that is love, he loves her past comprehension. And he will have her.

Though it is some distance, he decides he will walk to the museum. In fact, he will walk through the university campus. It is an old, traditional university, featuring gothic stone buildings with ornate spires enclosing green quadrangles. There is a path that passes the music building and in the summer, when the windows are open, you can hear the students practising.

But bad weather threatens. Rain is imminent. So he decides to go back and get his car, after all. It will make what he is planning easier.

At 4:00 p.m. he will exit the building by the basement service entrance as quickly after Lizbett leaves as he can. It is a door that is little used, mostly deserted. Pete, the security guard, is an old and trusted employee, an alcoholic who sometimes drinks on the job and often sleeps in his small booth. Melvyn is counting on that. Then he will drive to the intersection where he is hoping to find her, just down from the museum. He may catch her a little farther along the street. No matter. He will offer her a ride because of the weather and he feels sure she’ll accept. In fact, he’s convinced she’ll be flattered to be asked, to be alone with him. He knows she cares for him. They will go for a drive. They will talk about masks. They will talk about each other. He will be so happy and so will she. He will see to it.

He isn’t sure why he has chosen today. He is aware of an urgency within him to establish close, separate contact with her. It has been growing since the beginning when he was so surprised and delighted to have Lizbett in the class. But there, it’s as if she belongs to everyone, so keen are her campmates to associate with her. And she responds avidly to each, making him or her think she could be a best friend. She does this genuinely because though she is an extrovert, she is a sensitive and considerate one. She treats everyone equitably. In this way, she spreads herself thinly, but not noticeably, at least not to the kids. But she exhibits a special regard toward him. If she were older, he would consider her flirtatious, but instead she has a curious ingenuousness, a real desire to share his knowledge. He suspects it is her love of theatre. At the end of the week, when each person in the group “charges” his or her mask, Lizbett is the one who most understands the intimate duality of the mask. It is her grasp of that subtle and complex profundity that has so endeared her to him. She becomes her mask brilliantly, impulsively, spontaneously, allowing the mask to take her over. And her mask comes alive. He finds it thrilling just to think about it.

Today the class will be creating life masks: plaster casts made right on their own faces. He will choose Lizbett to be one of the first. It seems appropriate that on such a momentous day, a day of ritual, she will leave her real face behind.