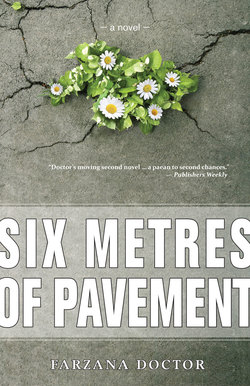

Читать книгу Six Metres of Pavement - Farzana Doctor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— 5 —

Affairs

It was shortly after Ismail’s return to the Merry Pint that Daphne became his favourite drinking buddy. Almost every day, she’d arrive just after her shift at a nearby women’s drop-in centre. She told Ismail once that she had a different personality during her workday, optimistic and helpful while she completed housing applications and distributed TTC tickets. By the time 5:00 p.m. rolled around, most of her cheer had run out.

Ismail found it surprising that Daphne had these two personas, on and off the job. But then, his work was in maintaining structures, not people. His almost singular focus was Toronto’s bridges and tunnels; the city’s great connectors. Ismail tested them for their soundness, inspected them to ensure they wouldn’t fall down on people, applying himself to his job in the same tedious and consistent manner in which he approached the rest of his life.

It was obvious that Daphne was worn down by her work. She arrived at the bar in baggy sweatshirts and jeans, only in the most sombre of colours. Her attire cloaked her slender figure, hiding ribs and hipbones that jutted out against her skin. Her face rarely saw the sunshine and her fair complexion was the kind that blushed tomato red when she was livid or embarrassed. By the end of the night, her long hair, usually pulled back in a messy braid, would be in further disarray. Later, Ismail would learn that it always carried a faint, but heady scent of lavender.

She was caustically cynical, and could find a way to flood anyone at the bar, not already depressed, with her hopelessness and despair. Ismail thought she was just his type. Besides her ability to bring people down, Daphne held great powers of suggestion. Mostly, she was a bad influence on Ismail, peer-pressuring him into drinking one, two, five too many shots of whiskey with her. When she was beyond drunk, her mood lifted and she could entertain Ismail with jokes and tales he found hilarious in the moment, but could never recall the following morning. She introduced him to several drinking games involving cards, dice, and whatever TV show was playing on the bar’s ceiling-mounted television. This held Ismail’s attention, amusing him for almost three years.

Two weeks after The Simpsons game that left Ismail questioning the wisdom of his ways, Daphne shocked him by joining Alcoholics Anonymous. They were in their usual spot at the bar, but she seemed more alert than usual, while he was already feeling a buzz.

“Wait. Really? You always called them a cult.”

“I was wrong,” she said with a shrug. “But there are some weirdos there. But most of them, they’re nice people.” Although she’d been to the Merry Pint since joining up, Ismail could tell AA was helping her. That night, he saw her order a ginger ale between beers, a sobering soda pop intermission. Her previous negativity about the program even seemed to be replaced with some hopefulness and a tentative loyalty to its teachings. Without a hint of sarcasm in her voice, she told him about the previous night’s meeting, using phrases like “one day at a time” and “higher power.”

“Well, isn’t it a contradiction to be here while joining AA?” he challenged.

“I’m going to go back tomorrow. I’m taking things slow. I’ve never been able to dive into things all at once.” Then she smiled, “Plus, if they really are a cult, it’s a good idea to do this gradually, right?”

“I guess it’s better to go sometimes than not at all,” he conceded.

“Come with me tomorrow, Ismail. It’ll be fun.” He raised a skeptical eyebrow, but she continued, her tone growing serious, “I don’t know a lot of people there yet. It would be good to have a friend with me.”

Ismail didn’t answer just then, and she changed the subject. But while she talked about a new policy at work that was annoying her, he considered her invitation. The pains in his side had returned, and he was embarrassed to go back to see the doctor after his three-year relapse. Besides, Nabil was on a new campaign of nagging, scolding him for his excesses during his weekly fraternal phone calls. By the end of the night, he and Daphne had made a pact to leave the Merry Pint together.

— * —

The day before José’s funeral, the young teller closed her counter and guided Celia away, touching her gently on her elbow. They went to the manager’s office, a glass box that faced out to the rest of the bank. She’d never been in an office like that; José had always been the one to do the banking. She was offered a cup of coffee and a seat in a plush leather chair. The teller spoke softly to her, in Portuguese.

Celia settled into the comfortable seat, approving of the special treatment she was being given as a widow. She looked out the glass walls of the office, sipped her coffee, and watched the tellers’ line-up snaking along velveteen barrier ropes.

There were hushed voices in the corridor. She strained her neck to see the teller speaking to the manager just outside the door, their faces just a few inches apart. Although their blazered backs faced her, she could make out a few words that sounded like overdraft, unaware, withdrawal. Celia watched the teller return to her counter, and within a few moments the manager appeared, a short balding man with a grim expression. He sat down, cleared his throat, clutched at his desk with tight hands. He showed her all her banking records on the computer, pointing to rows and columns of light blue numbers that made no sense to her.

The manager looked away from her and back to his screen. She wished that his office hadn’t been made of glass walls, an aquarium that barely contained her tears.

After the funeral, she hadn’t much time for crying. She sold the house, José’s old truck, most of the furniture, all the things that had marked them as successful people. Most of her possessions, anything of value, were signed away, auctioned off, bargained down. She kept for herself only a little furniture, her clothing, and a few keepsakes. All José left her was a small pension that she’d have to wait to collect on her sixty-fifth birthday. At least the government was more generous than he, delivering her a small survivor’s benefit once a month.

Her children assured her she’d never want for anything, but she knew Lydia and Filipe were just managing on what they earned. She had food and shelter and family, and she knew she should be grateful. But still, she longed for so much more.

— * —

Ismail and Daphne attended the Monday, Wednesday, and Friday 6:30 p.m. Hope for Today meetings at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health on Queen Street West, becoming regular, if somewhat ambivalent, converts. After meetings, they went for coffee and shared a new, sober intimacy that Ismail found almost as intoxicating as a shot of fine whisky.

He told her about Zubi’s death and Rehana’s rejection and she didn’t judge him for it. Soon, she started to share her own terrible past: her abusive parents, feuds with four siblings, and her early teenage troubles with cocaine. They developed a closeness that had been impossible while they were drinking buddies. To him, she was like a good therapist, inviting him to talk about Zubi, spurring on angry rants about Rehana, and offering hugs. Ismail’s memories became less ubiquitous and more manageable now that he wasn’t alone with them.

It was no surprise that the pair soon began sleeping together on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. Their therapeutic routine was AA at 6:30, coffee and confession at 8:00, and sex at 10:00, always at her place. Ismail never slept over and was home by 11:30. They carried on like this for many weeks, the AA and their deep talks a kind of heady, dry-drunk foreplay. He started to think they might make a go of a relationship until she finally worked up the nerve to tell him that they had to stop sleeping together because she was gay.

“No, you’re pulling my leg!”

“It’s true, Ismail. It’s something I’ve known for a long time but never admitted to myself. I guess not drinking all this time has made me finally come to terms with it.”

Ismail stared at her, dumbfounded.

She laughed and said, “Isn’t it great? I’m not just a drunk, but I’m a gay drunk, too!” She beamed a self-mocking grin at him, showing off her coffee-stained incisors and the little gap between her two front teeth that Ismail loved.

“But … it can’t be!” What Ismail really wanted to say was: But what about me? In his mind, she couldn’t be gay because they were dating. She was his first real relationship since Rehana. Visions of a future containing the two of them together, visions Ismail didn’t even know he had, came apart like a poorly fitting puzzle. He realized he’d been fantasizing about Daphne eating dinner at his house, perhaps moving in, and meeting his family. The whole she-bang.

“I’m sorry if this is coming as a shock to you, Ismail. I’ve been thinking about it for a long time, but I wasn’t ready to be open about it. And, well, now I think it’s better if we went back to being friends. I mean, if I’m really going to come out as a lesbian, I shouldn’t be having sex with men, right?”

Ismail was only half-listening, considering instead the Wednesday night they’d shared just two days earlier. Her fine hair had grazed his shoulder as she’d laid in his arms. He’d trailed his thumb up the length of her spine, tracing each bony bump. She’d stroked his chest, running her index finger over a small scar just above his sternum. The skin there had never healed properly, thickening and turning pink. She seemed to like that spot, returning to it often, rubbing it into smoothness. She asked him once how he’d gotten it, and he avoided telling her the truth, although he could have, in her dark bedroom.

“Really. I am sorry,” she said, filling the silence, interrupting his reverie.

“But … what about … all the times we’ve been … together?” Ismail sputtered. He knew he should have been scanning his brain for something appropriate to say, perhaps trying to remember the city-sponsored mandatory diversity trainings he’d attended, but all he could think of was how terrible he felt that she was breaking up with him.

“How can you be gay if you can have sex with men?” Ismail asked, his voice cracking. Thoughts of personal responsibility tripped through his confused head. Did I drive her to this? Is this further evidence of my personal defects?

“It’s not rocket science, Ismail,” Daphne sighed, sounding impatient. “I’ve been pretty much in denial my whole life about almost everything. Quitting drinking has helped me realize that. And, you know, it’s not hard for women to have sex with men even if they are not that into it.” Ismail fidgeted in his seat and thought back to their mediocre lovemaking. What had all that panting and moaning been about then? His ego bruised, he slumped back in his chair, crossed his arms over his chest. His armpits dampened through his poly-cotton shirt.

“Oh come on, Ismail. Don’t feel bad. We had some fun together. And we’ve become good friends these past couple of months, haven’t we? We’ll still be friends, right?” she cajoled.

Ismail sighed. It wasn’t the sex he was afraid of losing, but the evening chats, the pillow talk, the warmth of human skin. The possibility of something more. He closed his eyes, took in a couple of deep breaths, and tried to hide his hurt feelings.

“Yes, well, I suppose this is good news for you, Daphne. We are on the path to a more authentic life, aren’t we?” He strained to remember an AA slogan that would fit the situation, but found none. They clinked coffee mugs, exchanged platonic hugs and parted for the evening.

Ismail resolved to be a friend and to support her new homosexual life. On the following Monday evening, at the café across from the mental hospital, he pulled from his briefcase a library book entitled, When Someone You Love Comes Out of the Closet, which he’d read cover to cover over the weekend. She picked it up, thumbed through its chapters, a blush reddening her pale complexion. She must have been very pleased with Ismail, because she invited him over that night. So relieved was he to be asked back to her apartment, that Ismail didn’t raise the obvious contradiction of her being turned on by gay-positive self-help books. He worked extra hard to please her and perhaps he was successful, but he couldn’t be sure. He wished her good night at eleven-fifteen and prayed that things were back to normal.

When Daphne didn’t invite him to her bed after coffee later on that week, or the week after, Ismail borrowed Lesbian Lives, Lesbian Loves from the Parkdale Library, avoiding eye contact with the librarian as he checked out. He sheepishly displayed it on the laminate table while he and Daphne chatted over coffee, hoping it would serve as a paperback aphrodisiac. Finally, after two hot chocolates and a lengthy debriefing on Wednesday night’s Hope for Today membership, she acknowledged the book. She dispassionately read its back cover and then thanked Ismail for being a good friend.

On his way home, he tossed it into the library’s overnight drop-box, even though he’d only scanned its first chapter. He turned away from the library and glumly stared at a globelike metal sculpture that had been installed just outside the library’s doors. A fountain spurted up water from its centre, splashing its rusted beams and leaking rivulets onto the sidewalk. He fished in his pocket and threw a linty nickel into the pool, not bothering to make a wish.

Ismail could tell that Daphne was growing less interested in his company. She had already substituted some of their meetings for ones downtown where she was meeting other gay women in recovery. He imagined her attending gatherings with Birkenstock-shod women flirtatiously carrying on twelve-step banter.

Weeks later, Daphne admitted that she’d been dating someone from one of those meetings. Ismail warned her about starting a relationship with someone new in recovery, reminding her of the Program doctrine not to date during the first year. She didn’t listen to his counsel, and soon Ismail was twelve-stepping without her. He rarely saw her at their Hope for Today meetings.

In total, Ismail stayed in AA for 197 sobering days. After Daphne stopped being his comrade in abstinence, he got down to business and earnestly worked through steps one to eight, hoping to find the Cure for Bad Memories. He got hopelessly stuck at Step Nine, Making Amends. He couldn’t fathom what sorts of amends were possible in a situation like his; what could he offer his ex-wife, his baby child, or God, to make up for his sins?

If Ismail was truly honest with himself, he might have admitted that by Step Four, when he compiled his moral inventory, he was missing Daphne, The Merry Pint, and growing cynical with the self-help doctrine. He never fully believed he qualified as a true alcoholic, anyway. At meetings, while others rolled their eyes, he used words like “coping tactic” or “survival strategy” instead of “addiction” or “disease.” He supposed he was not a good follower.

He retreated to the bar, dejectedly dropping in for soda water and conversation, hoping that Daphne would show up. The old regulars welcomed him like a prodigal son returned, forgiving him his absence. Ismail was grateful to still belong. At first, he managed to pass his evenings there with soft drinks, but later, he’d have the odd beer. Once in a while a woman with smoke in her hair kept him company. But going to the Merry Pint never felt quite the same without Daphne.

How he longed for her! After Daphne abandoned him, the old memories rushed forward again. A new set of dreams plagued Ismail, always with him looking through the rearview mirror at Zubi in the back of the car. She’d sleep peacefully, her small body nestled in the baby seat. He’d look away for a moment, and when his eyes roved the mirror again, her seat would be empty.

He didn’t know how to cope without his old friend. He considered becoming a drunk again, regrouting his bathtub, having more meaningless sex. But he knew none of that would work. And so he gave in, gave up. They lived on, the memories and Ismail, cohabitating sometimes fitfully, sometimes peacefully, at his little house on Lochrie Street. The irony was that his mistake, the biggest of his life, was one of forgetting.