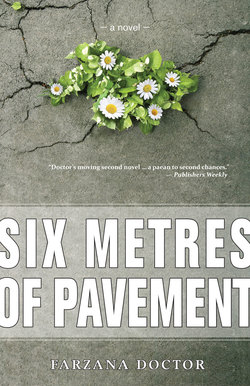

Читать книгу Six Metres of Pavement - Farzana Doctor - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— 9 —

Sweeping

Ismail’s next widow sighting was from behind the cloak of his living-room drapes. It was a cool December day, and she wore only a long, dark cardigan over her dress. A plain black cotton kerchief covered her mostly grey hair. Ismail squinted through the streaked glass, trying to determine her age. She swept the sidewalk in front of her house, her stooped posture and slow movements making her seem much older than he guessed her to be.

At one point, she straightened up and peered in his direction, perhaps sensing his presence. Ismail stood back and after a moment, he parted the fabric again. He saw that she was no longer looking in his direction, her attention being diverted by someone calling out to her from the doorway. She replied in Portuguese and gesticulated crossly at her daughter, Lydia, who strode out of the house, carrying a black woollen coat in her arms. Ismail drew closer to the window again, and opened it a crack so he could hear better, too.

Ismail didn’t know much about Lydia, except that she seemed a friendly enough woman. She, her husband, and young son had moved in a few years ago. He noticed they hung a Liberal candidate’s sign on their fence during the previous federal election (Ismail also voted Liberal, but preferred not to advertise this), built a new porch, and planted flowers out front that bloomed well into the cold months. Earlier that year, Ismail had admired the size of Lydia’s Black-eyed Susans.

Lydia’s voice rose, penetrating through the crack of his window, distracting him from all matters botanical. “Mãe, it’s cold out!” she yelled. In the same scolding tone, she said something in Portuguese and draped the coat over her mother, who tried, unsuccessfully, to wave her off. Lydia took hold of her mother’s arms, struggling to coax them into the sleeves and after a bit of pushing and pulling, Lydia won the battle, and her mother admitted defeat, standing obediently, like a preschooler, while Lydia fastened each big button from her mother’s knees to her chin. How the young treat the old. What insolence! Let her be! he protested silently from his post. There was something in how the widow allowed her daughter to dress her that told him her acquiescence had chilled her more than any late autumn winds could.

Lydia marched back into the house, blowing warm air into her bare hands. Only then did Ismail notice that she was dressed in a thin T-shirt, jeans, and bedroom slippers. The widow turned away from her daughter and looked across the street toward him. Beneath her tired expression, he saw that she had a pleasant face. He recalled that her irises were shaped like flowers.

She stared back at him blandly while he attempted to overcompensate for his presence at the window by grinning and waving gaily. She did not return the gesture, and so he quickly retreated behind the camouflage of his curtains, feeling foolish.

— * —

The bustle of her daughter’s household encircled Celia but couldn’t break through her lethargy. The days became endless and the nights short. She wished they would reverse themselves so that she could sleep sixteen hours and be awake for only eight. Sometimes she’d lounge in bed as long as possible, squeezing her eyelids shut, willing herself back to unconsciousness, but her treacherous body rarely allowed her to sleep beyond sunrise.

She’d been busy all her life, and there had never seemed to be enough time in her day for all the many tasks she needed to do: the cleaning, cooking, caring for sick children, laundry, and gardening never seemed to end. When the kids were young, she’d even managed to take in a small brood of the neighbours’ children to open a small at-home daycare. The days flew by. But on Lochrie Street, time slithered like a snail, dumb, slow, with nothing to direct it.

But that Sunday afternoon was different. As she sat at the front window, she looked out at the sidewalk and irritation crackled through her. The blustery winds of the night before had blown garbage onto the walk. And the dust! So much of it coated the normally white sidewalk. Usually, her lassitude allowed her to ignore such trifles, but on that day, dust and garbage were urgent matters. She rose from her perch at the window and went looking for a broom.

She stepped outside, and as she worked, she felt a little of her old strength returning, her muscles stretching and straining with each movement. A steady energy spread from her body up to her brain and she found herself humming a popular song she’d heard drifting from a neighbour’s window last week. She couldn’t remember the words, but the melody was familiar: Da da dee. Dum dum da. Da da dum. Dum dah!

She lifted her face to the sunshine, sniffed the air, and admired the blue sky above and sensed she wasn’t alone. She looked across to the Indian neighbour’s house and glimpsed him peeking through his curtains. She didn’t mind. After all, she’d been the one watching him these past few weeks. Perhaps she liked the thought of a man, and that man in particular, looking at her, reciprocating the watching. She blushed as she recalled the day she’d seen his thin legs and privates. He wasn’t an unattractive man, certainly. She hummed a little louder.

She didn’t know why Lydia had to come out right then and ruin her mood. It wasn’t so cold out and for once, she’d been enjoying herself. She didn’t need a coat. And more than that, she wished the man hadn’t witnessed her daughter treat her so stupidly. After Lydia forced the coat onto her, she felt all her energy drain right out of her, down her legs, out her feet, and pool on the sidewalk. She left the broom on the lawn and went inside to take a nap.