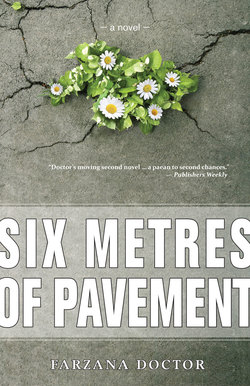

Читать книгу Six Metres of Pavement - Farzana Doctor - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление— 4 —

Arresting

The vestiges of a bad hangover from the previous night’s Simpsons game were still with Ismail the following evening. He’d had a terrible day at work, unable to concentrate during his unit’s third-quarter budget meeting. His unsettled stomach had him tasting bile a few times that morning. By the time work ended and he was walking to the Merry Pint, he had determined to quit drinking, a resolution he’d made many times before. Soon. I’ll do it soon. Today will be my last for a little while. Then, tomorrow …

The cravings whispered their sweet nothings in his ear: A cold beer would be perfect right now, what a terrible day! Cold on the tongue, warm in the gut …

He endeavoured to drive away those thoughts with a mental list of why he should stop:

1. Work performance suffering.

2. Stomach perpetually upset.

3. Spending too much money on drinks.

The quitting side prevailed for a minute or two, almost changing his mind about going to the bar. But then the drinking side, staggering and steadying itself, reasoned: You really want to try quitting again? It won’t work, you know. Besides, you can handle one.

Ismail never related to the proverbial rock bottom that most alcoholics talk about, where people lose their lives to alcohol. He rationalized that his lowest low had already come and gone, a rocky bottom that still left him scraped and skinned at the knees. In his mind, drinking couldn’t possibly take him lower than that. In fact, alcohol often rescued him from that barren place.

He knew it was ironic to be making plans to quit drinking while entering a bar (in fact it sounded like a bad joke: A man walks into a bar …), but a compromise between the two sides had been reached: Okay, tomorrow. Tomorrow I will stop. I’ll just have one tonight and then go home. Hair of the dog … He saw Daphne at the bar in her usual seat, her hand clasped around a beer glass, and Ismail felt a rush of tenderness and camaraderie for her. At the same time, worry bubbled up. Only one drink. Remember, no matter what Daphne says, just one drink!

“Hey, Ismail. I saved you a seat,” she said, smiling affably, sliding her jacket off the stool beside her.

“I’m just here for one tonight, Daphne. I overdid it last night. I have to go home to bed early.” He climbed up onto the stool, balancing uncomfortably, his feet barely brushing the ground. He gestured to Suzanne, the regular bartender.

“No worries. I’m probably going to head home soon, too. I’m keeping it light tonight.” Suzanne headed their way, carrying a fresh pint of beer, the froth sloshing a little over the glass’s rim. Daphne gulped down the last of her beer, and exchanged her empty glass for the full one. Ismail had watched her do the same thing with cigarettes, too; lighting one with the smoking butt still in her mouth. He ordered a Blue for himself.

Within an hour, Ismail had abandoned his self-imposed limit and bought the next two rounds. He was on his third and Daphne on her fourth or fifth when the police arrived.

A pair of officers, one tall and white, and the other slightly shorter and South Asian, approached Suzanne, asking her something Ismail couldn’t hear. Then they swaggered along the length of the bar, pausing just long enough to study his and Daphne’s faces. Ismail reflexively averted his eyes, looking down into the depths of his beer glass. A warm breeze of manly smelling cologne wafted by as they passed.

“Fucking pigs,” Daphne muttered. Ismail shushed her before she could say more. Alcohol usually made her prickly edges soften, but once in a while something could provoke her into an intoxicated belligerence. “Useless sons of bitches,” she hissed once they were barely out of earshot, “coming in here to find someone to beat up, I bet.” Daphne carried on with her venting while Ismail watched the police exit from the back-alley door. He didn’t much like their presence either, but for his own reasons.

Ismail would never forget his arresting officer, Bill Todd, a man whose surname was also a first name. He was middle-aged, with an East Coast accent and a paunch that strained his shirt buttons. Puffy skin bags rested under his blue eyes. He surveyed Ismail’s crowded cubicle, a nine-by-nine space large enough for a desk, filing cabinet, and a couple of chairs, and suggested that they speak somewhere more private. The office was quiet that afternoon, and so Ismail assured him it was fine to talk confidentially. He invited Bill Todd to sit down, and offered him a cup of coffee. Although he didn’t often speak with police in his role at the City, their responsibilities sometimes overlapped and he assumed the matter had something to do with a tunnel or bridge, matters under his jurisdiction.

Bill Todd declined the coffee. He peered cautiously into the vacant neighbouring cubicles and then sat down only after Ismail did. His careful movements made Ismail grasp the seriousness of his visit and his body responded before his mind, sending perspiration to his palms and armpits.

“What can I help you with, Officer?” he asked, his voice cracking slightly, betraying the outwardly calm countenance he was trying to affect. “Is this about a municipal issue?”

“No. I need to ask you a few personal questions, Mr. Box —,” he said, hesitating and reading the silver name plate at the front of his desk. Nabil had gifted him with it the previous year, on his thirty-fourth birthday. Everyone needs a spiffy name plate, Ismail.

“It’s Boxwala. Personal questions? About what?”

“Yes, Mr. Boxwala —” he said, again consulting the name plate.

“— has something happened to my wife? Has there been an accident?” Ismail interrupted. He slipped a handkerchief out of his pocket and wiped his damp hands, but quickly stopped and put it away when he saw the officer observing him. His heart began to race and the air felt hot and stuffy.

“It’s not your wife. Mr. Boxwala, do you own a Honda Civic, with the license plate number —” Ismail didn’t hear the rest. He instantly understood what was wrong. Zubi. His eyes lost their focus, and everything seemed to vibrate. Ismail’s mind dashed ahead of him: I took Zubi to daycare this morning, didn’t I? He tried to picture the daycare’s doors, its hallways, her teacher, but couldn’t. He stood up to get more air, but no matter how much he inhaled, there still there wasn’t enough. He understood that the reason for the officer’s visit was in the backseat of his car, just as he’d left her, asleep, her soft black hair resting against her baby seat.

“Excuse me, I must go, I have to check on something —” Ismail said, rising from his chair, stepping around his desk. He wanted to go backwards in time, get Zubi from the car, parked just a few minutes away. And then he would take her to daycare as he should have. Bill Todd stood up and blocked his way.

“Please sit down, Mr. Boxwala. Sit down,” he repeated sternly, his beefy hand gently guiding Ismail back around his desk and into his chair.

“You don’t understand, you see I must go check … I usually drop the baby off first … my daughter, Zubi … then my wife at her work, and then I come to work … but the order got changed today … I have to go get my daughter. Please, let me go to her!” Ismail sputtered, gasping for breath.

“It’s too late, Mr. Boxwala. She was found about an hour ago.” He barely heard the words; they were travelling away from him, faint, barely comprehensible syllables.

“What? What do you mean? Then she is … okay?” Ismail grasped for any possibility, any hope that Zubi was all right. Bill Todd shook his head, bit his lip, grimaced. For the first time during his visit, he didn’t make eye contact with Ismail.

“No, it can’t be. Oh no … oh no … Zubi!” Ismail wailed, forcing himself up out of his chair again. “Please, I have to go see her.” His mind refused to let go of the fantasy that Zubi was still alive: Yes, of course her crying would have alerted a pedestrian, a Good Samaritan who would have called the police, freed her from the car …

“It’s too late. She was found in your car, like I said, about an hour ago. Deceased. Most likely from the heat.” This time he did make eye contact, icy blue ponds.

“Oh no.” Ismail gasped, holding his chest.

Each time Ismail remembered this next part of the story, he viewed it in near-cinematic slow motion. A millisecond before he closed his eyes and fell to the ground, he saw Officer Todd’s anxious expression as he lunged forward to steady him. A co-worker, young, pretty, recently hired Chitra Malik, peeked into the cubicle, alarmed by the commotion.

He had no fear as he lost his balance and the world spun away from him. Rather, he had an amazing and naive thought: he believed he was dying, his life being snatched up in a great dizzying whirl, and he was on his way to greet little Zubi so that he could hold her one last time. He might cuddle her on his lap, kiss her sweet-smelling head, and then, in the vast wisdom of all things celestial, switch places with her.

Daphne had finished ranting and was now watching him with curious eyes.

“What?” he asked nonchalantly.

“You’ve kinda been staring off into space for the last few seconds.”

“Oh, sorry. Just tired I guess.”

“It doesn’t matter,” she said and turned her gaze to the back doors, where the police had re-emerged. They travelled through the bar, the same way they’d entered, taking their time to scrutinize patrons. Before they could reach the front where he and Daphne sat, Ismail pulled some bills from his wallet, and muttered a quick goodbye to Daphne.

He walked the few blocks home, the glaze of intoxication making the sidewalk crooked beneath his feet. At his front door, he searched his coat and pants pockets for his keys, fumbling past loose change and bits of paper. Eventually he found them within his coat’s inside breast pocket, an unlikely place, and he wondered how they’d gotten there. Dangling before his eyes, they seemed unfamiliar, like someone else’s misplaced keys.

A silver key met its matching lock, a bit of grace on a graceless night. He crossed the threshold, and although he knew the house was empty, he sensed he wasn’t completely alone.

— * —

It was ten o’clock already and the nurse who came to check José urged Celia to go home for the night. “Have a rest, take a shower. He’ll still be here in the morning,” she said, clicking her pen open and scribbling something down in a chart. She efficiently moved around the bed, inspecting her husband’s limp body and the beeping machines that sustained him.

Lydia had been by earlier, bringing food during her lunch hour and a change of clothes after work. Celia hadn’t thought to ask for toiletries, and so she’d had to swish her mouth with water and wash her face and armpits with the harsh cleanser and brown paper towels in the public washroom down the hall. She guessed the nurse could tell she needed a bath. Later, she questioned why it hadn’t occurred to her to just go down to Shoppers on the first floor for travel-sized containers of toothpaste and face cream.

She picked herself off the chair, glad for the nurse’s permission to leave. By then, she’d spent two days at her husband’s sleeping side while others in the family had come and gone. The doctor had checked in twice and reassured her that his condition was improving. He’d looked at her sternly, as though José’s angina was her fault, and warned that there’d need to be lifestyle changes. She’d nodded dumbly and listened as he discussed recommendations for medication and future surgery.

She decided to walk home, even though Antonio, her son-in-law, had offered to come pick her up. She’d told him she’d take a cab, didn’t want to make a fuss. Anyway, she was glad to walk after sitting for so long, and the crisp night air was fresh against her skin.

At home, she took a shower, and then listened to eight messages of concern on the answering machine, pressing the orange button that meant they’d be saved. She would ask Lydia to call everyone back from work the next day. Hopefully she’d remember the password she programmed in for them; Celia had forgotten it long ago.

She wandered the quiet house and peeked in on her sleeping mother. She watched as the bedclothes rose and fell, something she used to do when her children were small, checking to make sure they were still breathing. José used to tease her for it; he rarely feared for their safety the way she did. She wished now that her mother was awake to comfort her, to bring her a plateful of fish and potatoes, to tell her what to do next.

She looked at the wall clock, calculating that it was only nine-twenty in Vancouver, and dialed her brother, Manuel. No one picked up. She rooted around the fridge for something to eat and found a bottle of wine José had opened a few days ago. She poured herself a tall glass, gulped it back, and then turned off the downstairs lights. By the time she landed in her bed, she could feel the cool wine heating her belly and carrying her off to unconsciousness.

— * —

Ismail lay in his bed, his head still cottony from the booze. It was a good way to fall asleep; his muscles relaxed and thoughts slowed down until they almost stopped. But alcohol wasn’t fail-safe. Its soporific effects only lasted so long before he’d dream his way into memories that would wake him in the middle of the night. That night, at 3:00 a.m., he saw Zubi’s ghost at the foot of the bed, staring at him blankly. Then her pupils grew large, darkening her gaze, and he grew afraid. From somewhere outside the window, he heard Rehana’s shrill voice yelling, “You forgot her! How could you have forgotten her?”

He backed up against the headboard with such force that he knocked himself fully awake. He switched on the bedside lamp, exorcizing Zubi and Rehana from the room. He left the light on a few more minutes before settling himself down to rest again. Before he fell asleep, he repeated the resolution he’d made earlier that evening: to stop drinking.

Right after the divorce, almost a year after Zubi’s death, he saw a psychologist for forty-eight sessions. Almost a year, but not quite. He attended each appointment faithfully, following the mandate of a manager who felt he needed assistance with his “post-divorce job performance.” It sounded like some kind of human resources category, but when Ismail looked it up in his employee handbook, he couldn’t find it.

All of Ismail’s colleagues signed a condolence card with platitudes to “take care” and “time heals all wounds,” but none attended Zubi’s funeral. A great cloud of silence crept over the cubicles of the Transportation Infrastructure Management Unit when anyone came close to mentioning the circumstances of his daughter’s death, at least when he was present. Over the years, a new life story was created for Ismail at the office. He became a “bachelor,” a “loner,” “single without kids.” He didn’t tack any family photos onto his cubicle walls. No one expected him to attend the annual office holiday party.

Soon after therapy ended, Ismail found an almost perfect way to dampen down his memories. He’d been walking home from Dufferin Mall one Saturday when he saw a large yellow vinyl “grand opening” sign flapping in the wind above what used to be an empty storefront. For years, a dusty display of men’s briefs occupied the front window, and he’d often wondered if anyone was going to come along and revitalize the old haberdashery. The new owners transformed the property into The Merry Pint, a typical-looking drinking hole, with a few tables spread along one side and a long bar down the other. The back had a refurbished pool table and a few booths where local drug dealers set up shop. The lighting was always on the dim side, although its south-facing windows drew sunshine on bright days. The bathrooms downstairs were kept fairly clean, but still managed to exude a faint smell of urine.

That day, the fluttering banner advertised, “Come in for a $1 beer — this week only!!!” and so Ismail followed its enthusiastic command, and went inside, intending to have a cheap drink and then go home to his leftover Patak’s curry. It was during the frightful restructuring days at work, and perhaps he’d been a little more on edge than usual. That one beer turned into two more, drinks that provided him with a giddy, enlivened intoxication he eagerly welcomed. Until then, he rarely drank, except on special occasions: a sip of champagne at New Year’s, a glass of wine at dinner with his brother’s family.

And then there was the companionship; amiable chatter from a few patrons who, along with Ismail, would soon become Merry Pint regulars. By his third visit, he realized that none of the others recognized his name, were not interested in his history whatsoever. He was welcomed into their drunken tribe, and together, they enjoyed a perpetual present.

At first, a few drinks once or twice a week permitted him a respite from his life. Then, those drinks weren’t enough, and he found himself there every night after work, drinking a few, talking nonsense with the regulars and eating lukewarm battered cheese until he was sleepy and nauseated. Not surprisingly, the tipsy fun was soon replaced by a dull, drunken routine:

Sleep. Work. Beer. Cheese. Sleep. Work. Beer. And so on.

This regimen had great staying power, but of course, it finally dawned on Ismail it wasn’t sustainable. About a dozen years into his tenure at the Merry Pint, just after his forty-eighth birthday, he awoke with a strange radiating pain in his side, uncomfortable enough to force him to go to the local walk-in clinic. After an hour’s wait, the young doctor took his history, twirling a strand of blond hair with her left hand, while she took notes, in green ballpoint, with her right. Her eyes widened when he calculated that he’d been drinking heavily for over a decade. Ismail attempted to avoid looking down her tight blouse or noticing her low-riding trousers while she strapped on a blood pressure cuff and listened to his quickened pulse.

In serious tones, she suggested residential alcohol treatment, and warned him about high cholesterol and liver disease. She sent him away with ultrasound and blood test requisition forms and called him in two weeks later to review the results. Despite the fact that she reminded Ismail of Britney Spears, he took her counsel seriously, shocked that he had let things advance to such a sordid place.

So, two years before his fiftieth birthday, he tried for the first time ever to quell his urge to drink. For about eight months, he managed to quit the fried cheese, switch to light beer, and not surprisingly, lost about twenty pounds, returning to his previous slender physique. He visited Dr. Britney at regular intervals, and since the mystery pain had disappeared, she seemed pleased with his progress. He never told her he hadn’t quit drinking, that he’d only switched to light beer. Week after week, usually on a Sunday evening, he resolved to do so, making plans to take a few days off from the sauce. Some of the attempts lasted a day, maybe two. Most of the time, though, he spent his evenings hunkered down in his living room, sipping Blue Light and watching TV. Ismail’s Sony Trinitron became a nonjudgmental, consistent companion and a somewhat adequate replacement for his old drinking friends.

But it wasn’t as depressing as it sounds. Ismail discovered entertaining and productive shows on home décor, which reminded him a little of his old self, the person he’d been before Zubi died and Rehana left. Back then, he’d been a tidy sort, even slightly fastidious, according to Rehana, who hadn’t been used to a man who knew how to use a vacuum. He’d lost some of that while his drinking was at its worst. Rings of grime coated his bathtub, empties piled up by the back door, and dust and cobwebs accumulated in every room’s corners.

But from April to November of that year, Martha, Debbie Travis, and Mike Holmes motivated Ismail to bash down a living room wall, and install a skylight that let bright shafts of sunlight into his office. He painted the kitchen walls various hues of yellow and orange, back-splashed with new ceramic tiles, hung expensive-looking and pensive artwork in the dining room, and planted an attractive perennial garden out back.

With the encouragement of HGTV, he worked steadily, devoting himself to his projects each evening, weekend, and statutory holiday. He even used a few sick days for the really time-consuming and tricky jobs. As he destroyed places within the house that reminded him of the old days, he hoped to make homeless the memories that lingered long in that old row house.

Bad memories are like relatives who visit and overstay their welcome. Soon your irritation builds when night after night, you return home to find them lounging on your couch, or raiding the refrigerator. And bad memories can be a noisy lot, keeping you up late at night with their endless chatter. Sometimes, you rouse at night to find one of them standing next to your bed, pillow in hand, about to smother you to death.

Evicting them is futile, for memories are slippery and sly, able to find new hiding places and cubbyholes in which to live. They grudgingly vacated for a night or two, fooling him into thinking they were gone, only to make their appearance once again. When he repositioned his bedroom furniture to improve the feng shui, he found a pair of Rehana’s socks trapped behind the dresser, coated in pinkish-grayish dust. He brushed them off, and, unsure of what to do with them, meekly folded them into a tight ball and tossed them to the back of the closet.

One day while digging a hole for a new Rose of Sharon bush, he spied something buried a foot down in the soil. He poked it with his trowel, yanked it free from the earth, and held it in his gloved hand. It was a bright yellow car, encrusted in grime, just the right size for a toddler’s grip. Tiny cartoon faces peered out from its dirty windows: a father at the steering wheel, a mother in the passenger seat, and two children in the back. A gush of high-pitched babbling filled the air. Ismail looked around for children in neighbouring yards, but there weren’t any. He closed his eyes and listened until the sounds stopped.

Sometimes, on rainy days, he’d enter Zubi’s nursery, an abandoned, closed-up area of the house. He considered redoing the room, perhaps turning it into a mini-gym. He planned to donate the dusty pine crib, dresser, and change table to charity, but never managed the task. At least the closet was mostly empty; Rehana had packed up Zubi’s clothing, photo albums, and toys long ago. She left behind three framed photographs of Zubi on the dresser. He hadn’t moved them from where they’d been placed, and could hardly bear to look at them.

Over the years, the room turned musty and the wallpaper shabby, its edges peeling and curling up into itself. Rehana and Ismail had hung the wallpaper together, one of their first home decorating efforts. They had an argument about whether to go with a balloon or teddy bear motif, and as usual her choice prevailed. Rehana steadied a ladder for Ismail, and her seven-month tummy got in the way, rubbing up against the paste. After he’d hung the paper, Ismail painted the ceiling sky blue, with puffy white clouds, so that their baby would have something soothing to look at when she woke.

His renovations stopped there, at the threshold of Zubi’s room. In the rest of the house, the lovely walls, new finishes, and garden left him feeling lonelier than ever. He returned to the Merry Pint for solace, and within days, was drinking to get drunk again.

For a spell he had cheerless sexual encounters with the not-so-merry, half-sauced women he met there. They seemed to efficiently manage their dance cards through some kind of unspoken agreement with one another, switching partners on alternate nights. Ismail was among the dozen or so men who frequently vied for their attentions, buying them drinks, going home with them on a weekday evening. The luckiest, the ones most in the women’s favour on a particular week, got a Friday or Saturday night of inebriated tangoing.

They filled the vacant space in Ismail’s cold bed, their panting or snoring distracting him a little from the ghosts who lurked at night. But like the rest of his survival tactics, the results were temporary. It took him a few months of drunken sex to stumble into the realization that middle-aged white women with smoke in their hair can’t erase memories. He gave them up, and instead, found Daphne.