Читать книгу Talkative Polity - Florence Brisset-Foucault - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

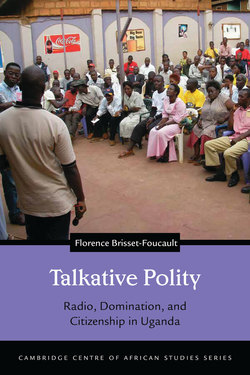

KAMPALA, AUGUST 2008: A CROWD WAS SQUEEZED TOGETHER under a large thatched roof. People were trying to better hear the speakers taking turns behind the microphone. The venue was Club Obbligato, one of the capital city’s most famous bars. The event was Radio One’s weekly outdoor talk show, Ekimeeza. Between 2000 and 2009, shows like this mushroomed in Uganda, especially in Kampala, where around ten might be held every weekend. All followed a similar pattern: a weekly debate organized in an open space and broadcast live on radio. Most of them were aired in vernacular languages; one of them was in English.

Approximately three hundred people were gathered at the club that day. The topic was the attempt by several opposition political parties to create a common platform to put an end to the twenty-five years of rule by President Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) at the following elections. The audience was seated in circles around a large table that gave its name to the show: in Luganda, the language spoken by the Baganda, the most numerous ethnic group in Kampala, ekimeeza means “a round table” at which people sit to discuss issues.1

Seated casually at the table was the chairman, James Wasula, who moderated the discussions and called the orators to the microphone. He was surrounded by familiar faces; many were young men in their late twenties who came every week to practice the art of convincing crowds. Dr. Kayondo, however, was a middle-aged medical doctor who was part of the group who had initiated the debates back in 2000. As usual, he was leaning back by the pool table and enjoying the flow of speech. Not far from him were K.M. and H.N., often the only women in the audience.2 Seated next to the outside broadcasting van decorated with a large radio one logo, radio producer Lynn Najjemba was attentive to the reactions of the people in the audience. She was not the only one: famous or anonymous members of the Internal Security Organization (ISO), Uganda’s secret service, usually attended the show to monitor what was being said. Every weekend, political officials, and particularly members of Parliament (MPs), attended the debate. That day, John Ken Lukyamuzi, a former MP for Rubaga South, one of Kampala’s constituencies, and the president of the small opposition Conservative Party (CP), was seated at the table next to the chairman.

After an hour of debate and a long speech from an opposition supporter, the chairman called to the floor B.T., a thirty-one-year-old teacher. He was one of the most successful orators of this ekimeeza. A staunch supporter of the regime, his interventions were always funny and witty. Most members of the audience, including those who disagreed with the government, appreciated his oratory talents. That day, he set his mind on mocking the endless quarrels between opposition parties and the reluctance of some members of the opposition, especially from the Democratic Party (DP), to join the coalition project:

(Someone: shhhh) The cooperation [between parties] . . . The cooperation is very, very fine (laughs), and I want to appreciate the nature and the gut [with] which my colleague [the previous speaker] has established the moments of the [agreement] (laughs). [. . .] You are talking about bringing parties together, a cooperation. Mr. Chairman, a cooperation is very, very good. Even when a rat is fearing to cooperate with a cat (laughs), because that cooperation can lead either one to grow fat (laughs) or another one to die. . . . (laughs) In that cooperation, you can cooperate, but the people who are cooperating may not survive in that cooperation (laughs; someone: yes!). Mr. Chairman, when these people were trying to cooperate I was around Kamwokya [a neighborhood in Kampala] in Panafrica [a political club], and some guys from one party remained at Kamwokya eating pizza. . . . When the cooperation [meeting] ended, they said, “We didn’t know the time” . . . (laughs) [. . .] I have heard serious DP [people . . . ] saying, “No, we are not ready to be eaten.” . . . Then I said, “When shall you be eaten?” (laughs) When is the time to be eaten correctly? [ . . . ] And you see my worry, Mr. Chairman, because DP for political [reasons], DP has tentacles in the central [region] and if you want to emerge, you can’t get around DP, you have to take this into account if you want to move on. I know that my important colleague Lukyamuzi has a constituency (laughs) [This was an ironic remark as Lukyamuzi, who was part of the opposition coalition and who was present at the debate, had lost his seat in the 2006 elections], but despite that you still need DP! [. . .] You talk about being united, but you have people who run away from their parties. [. . .] What I want to say is that the cooperation is really excellent, but will these people manage to be together without fearing? I thank you.3

A year later, in September 2009, the government banned the ebimeeza. Since then, these radio shows have not been allowed back. This book is based on the idea that the ebimeeza and their ban reveal the complex ways in which legitimate speech and political personhood are imagined in the politically restrictive context that exists in contemporary Uganda. I argue that the ban tells us more about the Ugandan political culture and about Museveni’s regime than just that it is aging and becoming less and less liberal.

There were clear short-term political reasons for the ebimeeza—also called “People’s Parliaments”—to be prohibited. These included especially the growing tensions between the central republican state and the neo-traditional authorities of the Kingdom of Buganda: forbidding live outdoor talk shows was a way to curb radical royalist speech. However, I argue that this ban needs to be resituated within a longer time frame, as well as a wider context. To understand fully its significance, and the fact that it was approved by some of the very people who were directly affected by it (including opponents to Museveni’s growing authoritarianism), the ban needs to be resituated within the controversies the ebimeeza triggered once they first appeared in 2000, and within much older concerns about who was entitled to speak and how.

Having access to the local arguments about the existence of the ebimeeza, about the rules they should follow, the ways they should be organized—in short, about the way people should or should not “talk about politics”—gives us a heuristic insight into profound debates on the forms and the basis of citizenship. But such knowledge also leads us to a better understanding of the concrete exercise of power and the mechanisms of domination in a context often labeled as “semiauthoritarian.” Analysis of the ebimeeza shows why some things may be said in contemporary Uganda, and others may not.

The story of the ebimeeza and the controversies around them allow us to understand in detail the parameters of criticism and of the complex ways in which limits are imposed on the ways in which people may imagine themselves as members of a polity. What kind of political order was imagined and practiced in the ebimeeza? What kinds of speech did people value and why? What does the existence of the ebimeeza and their disappearance reveal about the Ugandan political society? In short, the ambition of this book could be summarized as understanding the imaginaries of political personhood at play in contemporary Uganda while not separating those imaginaries from the concrete and complex mechanisms of political domination in force under Museveni’s regime, beyond large and reductive dichotomies. By doing so, this book ties together the study of the polemical imagination of citizenship and the study of what is often called “authoritarianism,” or, in the case of Uganda, “semiauthoritarianism.”

Complicating the Picture of “Hybrid Regimes”

After the crushed hopes of the “third wave of democratization,” the concept of “hybrid regimes” was supposed to allow a closer understanding of political situations that include features presented as essential to democracy but also characteristics described as authoritarian.4 Interestingly, Museveni’s Uganda is often quoted as the paragon of the “hybrid regime” and characterized as “semiauthoritarian,” a regime that “remain[ed] basically authoritarian, but incorporated some democratic innovations.”5 According to this literature, semiauthoritarian regimes are characterized by the existence of competitive elections; the oscillation between a certain regard for human rights and civil liberties on the one hand, and their violation on the other; nepotism practices, corruption, and the abuse of power, but also the possibility to challenge such behavior through parliamentary politics, the judiciary, and the media.

The new typology that stemmed from this idea of “hybridity” (with categories such as “illiberal democracies,” “liberal semidemocracies,” “quasidemocracies,” “pseudodemocracies,” “semidemocracies” or “semiauthoritarianisms,” “competitive authoritarianisms” or “electoral authoritarianisms”) was indeed more precise.6 However, its heuristic value is not satisfactory when it comes to understanding the actual extent and parameters of the state’s power as well as the repertoires within which people living under a particular regime act and think in their daily lives.7

Within a particular regime, the ways in which control is carried out varies enormously according to the different localized and complex ways in which the state is socially embodied. The hybrid typology is often based on very broad indexes amalgamating complex realities into measurable variables that do not take into account the sociology and history of the state, its agents, or those of the populations involved. Typically, political actors are identified using large formal categories (the judiciary, the media, the military). The social histories of these groups or institutions, the ways they were formed through the amalgamation, the integration, and the exclusion of particular social actors, as well as their inner conflicts and debates, are largely erased. The daily negotiated dimension of power and repression, which are deeply intertwined in the social fabric, is overlooked. It is often forgotten that even in a context labeled as “authoritarian,” where the state can appear as homogeneously submitted to a powerful executive, it is in fact a competitive space. The state is crossed by social, political, and ideological differences and antagonisms, and it is entrenched within society as well as within the struggles that structure it.8

Typically, in the “hybrid” literature, changes identified as “democratic” are seen as strategic and reluctant concessions to external donors to legitimize the autocrat’s rule. Obviously, this dimension of instrumentalizing donors’ “good governance” agendas by top leaders should not be overlooked. But there is more to this than mere strategy. A sociological approach takes into account the complex working and sociology of the state in all its heterogeneity, including in its extroverted dimension, and provides a more comprehensive picture. What can be said, for instance, of the corporative interests of sections of the state? Of the interests of particular segments of the political and bureaucratic elite in pushing reforms or agendas that might be favorable to their own social advancement?9 The literature on these issues has demonstrated the heuristic value of analyzing political change as the result of a confrontation or accommodation of sociohistorical segments of society and their struggle for power, recognition, and access to the state, beyond the surface of “democratization.”10

This book relies on the principle that the exercise of power is intertwined with social relations and should thus be studied from the analysis of society (i.e., from the study of the socially entrenched daily interactions between groups and individuals). This approach should not stop us from studying processes of institutionalization and autonomization of the state. However, this book recalls that the negotiations at play in terms of how to speak about politics (for instance) involve actors who are ingrained with multiple social belongings, and who largely transcend the simplified dichotomy of a “liberal” civil society resisting an oppressive state.

Another concern raised by the idea of “hybrid regimes” is that it gives the impression that some dynamics and political actors within a political regime are fundamentally “democratic,” whereas others are fundamentally “authoritarian.” It thus often encourages a deductive and univocal reading of social and political phenomena (Does this dynamic, or this institution, favor “democracy” or not?) instead of letting emic meanings and unexpected consequences emerge from the field. Political action is analyzed only against this dual, univocal grid and not according to alternative, autonomous logics or social dynamics that might explain behaviors or outcomes in a different way, rather than just as the result of a great confrontation between forces that are fundamentally repressive versus forces that would be fundamentally liberal.11

We know, however, that power relationships are more ambivalent: rulers are also ruled, and the ruled can be oppressors.12 If we follow Foucault, forms of agency can emerge within or even from situations of submission.13 Consent is not univocal and total: It can be given to one aspect of political rule and not to others. It can mix support, criticism, and fear. Languages of authority, the politics of control, and even state violence sometimes appear legitimate to some.14 There is a “vast range of relationships to authority” that needs to be described and understood and that cannot be encompassed in a dualist framework.15

As Béatrice Hibou has shown, in situations labeled as authoritarian, the mechanics of domination also involve forces and dynamics that cannot be reduced only to the state, and actions or phenomena that might contribute to reinforcing a certain political hierarchy, but not necessarily intentionally.16 Even in contexts of strong political pressure and violence, people also act according to rationalities, interests, and agendas that do not necessarily intend to oppress or resist. The routine politics of violence and its negotiation, in particular, need to be taken into account; for instance, the interaction between a local police officer and the radio reporter working on a story, whereby both act according to a variety of distinct and local interests and rationalities. As we will see in detail, people might consent, desire, or submit to a certain social order that reinforces patterns of political domination while not necessarily supporting the regime.

A dichotomist framework cannot encompass this social thickness: these intertwined yet distinct rationalities, belongings, and historicities. Such a framework impoverishes the social experience of domination, the ways in which people live and interpret politics. This is obviously not to say that some people—indeed, many people—in Uganda do not suffer and pay a great price for defending the right to act or to speak as they wish, nor to minimize their effort, pain, or sacrifice. On the contrary, this book seeks to highlight and analyze the complex and manifold social implications of their struggle.

Understanding the Production of Media Speech beyond Normative Yardsticks

These nuances are all the more important to mention, as the apparent contradiction between the existence in Uganda of a vibrant and sometimes very critical media scene and the regular recourse to the coercion of journalists is often pointed out as the perfect embodiment of the “paradoxical” nature of semiauthoritarianism.17

Beyond the specific case of Uganda, treatment of the media is often used as a yardstick to evaluate how “free” and “democratic” a political system is.18 The literature on the media in Africa has been particularly marked by this normative dimension.19 News outlets are often assessed according to how strongly they contribute to (or jeopardize) peace, development, and democracy. But this clearly does not do justice to the wealth of actions and representations by media professionals in these contexts.20 Indeed, the daily elaboration of media discourses illustrates particularly well the ambivalence and social thickness mentioned above.

Insisting on the ambivalence of the position of the media toward the state obviously does not mean denying how Ugandan journalists are exposed to multiple repressive acts on a day-to-day basis. These acts range from distressing threats and intimidation to traumatizing beatings, violent police searches, recurrent arrests, exhausting legal proceedings, and the like. They occur in particular when journalists reveal cases of corruption, or when they cover military operations, the first family, electoral fraud, or street protests. The valuable publications of the Human Rights Network for Journalists—Uganda give precise and gruesome details of these acts, and the aim of this book is not to paraphrase this very rich source.21 It is enough here to state that even if they mainly rely on self-reporting by victims (which means that estimates are probably low because of the very routine character of threats), these reports show an expansion in the acts of repression since the end of the 2000s, in a context of the normalization of torture used against opponents and suspects; of growing illegal, close-range electronic surveillance; and the complete impunity of the security services.22 Many Ugandan journalists describe a rise in repression and the systemic hostility of police and army against the media, especially when covering street protests and electoral campaigns. In 2009, the official response to the so-called “Buganda riots” was an important milestone in the repression of media speech, involving the closure of four radio stations and the ban of the ebimeeza. In 2011 and 2012, the coverage of the “Walk to Work” protests, organized by an opposition coalition against the cost of living, was particularly risky and difficult. Beyond these spectacular moments, political and business elites routinely use varied means to influence media speech. Journalists often mention in interviews how political pressure can take direct as well as indirect roads, especially through editors in chief, who can act both as fuses and conductors of repression. Pressure is also exerted by newspaper owners and advertisers. Criticizing the idea that there is a fundamental antagonism between media and state power does not mean that there are no power relations between the two, nor is such criticism understating the very real risks media workers take when expressing themselves. On the contrary, such criticism should lead to a better understanding of these risks and constraints.

Several methodological precautions need to be taken when it comes to analyzing repression and more precisely understanding the parameters of political rule. Repression originates from a great variety of sources. It is not systematic and can be attributed to several variables, though it is not anomic or random. It can be analyzed and trends can be interpreted to understand the kind of speech state elites are ready to tolerate and the means they have to implement limits, as well as their relationships with media workers and with other state agents.

Journalists suffer and respond to repression in diverse ways according to their resources, their positions within the newsroom, their social and political trajectories, and especially the links they might have with state elites, as well as their political ideas. They can put together protection and negotiation strategies, and more or less have leverage with the authorities. The daily process of negotiation does not exclude the use of violence; far from it. Links with state officials can be a source of pressure and protection.23 Previous friendships from school or church, the politics of exile, or sharing the experience of fighting in the Bush War that led Museveni to power between 1981 and 1986 does not completely prevent coercion. But these dynamics can attenuate it, while at the same time being a source of political and psychological pressure. A media worker may, for instance, be warned of an imminent arrest, or of the hostility of a particular official.24 Compliance and criticism are often closely intertwined. Sociologists have shown that the revelation of big scandals by the press, for example, is not a sign of detachment and autonomy, but rather a sign of the intensity of the relationships between media and state (via the access to good sources within it).25 As mentioned, the state is a competitive arena, where officials, as anywhere in the world, strategically use leaks to reach their objectives. Media workers and state officials have mutual interests in being close and interconnected.26

The daily bargaining between criticism and pressure leads to different kinds of compromise: for instance, the use of anonymity, the decisions made by journalists regarding whether or not to publish information, to push back the date of publication, to pass over information deemed too dangerous to foreign NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) or news outlets, or to get in touch directly and privately with state officials to raise an issue of concern.27 Some topics and official events are covered as a gesture of good faith toward state officials, with the goal that more controversial articles will be tolerated.28 Actually, newspaper pages can be read as palimpsests of such negotiations. The layout itself may reflect this, as one editor in chief noted: “Offending paragraphs [could be] sandwiched discreetly into the back page.”29 Articles might be moved from the “Politics” section to the less controversial “Business” pages. Black-and-white close-ups of frowning opponents may be preferred to wide-angle color photographs of political rallies showing the crowd.30 Metaphors and tales are, as elsewhere, widely used as a way to toy with repression.31

Degrees of submission and collusion vary within the newsroom, and according to topics and sections of the paper. This is why broad labels (“private press,” “state media,” “opposition media,” and “independent media”) are too general to help understand the nature of the relationship between state and media, the way domination is exercised and negotiated. Also, such labels do not capture the depth and complexity of the repertoires of critique and political languages deployed: editorial choices have to be analyzed against the backdrop of the plurality of power sources, together with a long and complex history of political ideas. Moreover, journalists position themselves not simply “for” or “against” the government: the range of possible positions is wider and more complex. Nicole Stremlau has shown well how during the first years of the regime, newspapers such as the New Vision (belonging to the government) and the Weekly Topic (owned privately by three major pillars of the NRM regime) participated in building a consensus around the new political order the NRM was attempting to build following the Bush War, while openly taking on a mission to criticize the regime in order to “strengthen the revolution.”32 These papers fiercely denounced corruption and abuse of power, and in order to do so journalists used the very ideals the NRM was supposed to protect.33 At the time, the way these journalists worked reflected a desire to be integrated within the political and moral renovation project of the NRM, while trying to protect themselves from repression: the state was an object of both desire and fear. Support and criticism could be intertwined within the same article, as a strategy of protection but also in coherence with political and ideological trajectories that were common between some journalists and NRM officials.

As mentioned earlier, repression is far from taking place only in visible ways. Official justification often hides the genuine reasons why repression is triggered in the first place. Nevertheless, these justifications are worth taking seriously for what they are: official representations of what legitimate media speech is, in the eyes of the political elite. Of interest here are the effects of this official ideology of discourse: how this ideology was perceived and sometimes taken on by journalists and citizens, and the influence it has had on actual political speech.

The definition of what can and what cannot be said has often been enforced by the state through extrajudicial violence, but also through criminal law. This started as early as 1986, even though criminal condemnations of journalists up until now have been extremely rare.34 But beyond criminal law, what is of interest to us here is that some journalists actively participated in crafting this new media language during the first ten years of the regime, including some who published very aggressive investigative pieces against powerful officials, especially journalists from the Weekly Topic, the New Vision, and the Monitor.35 Even defenders of “free speech” could desire the enforcement of limitations and see this enforcement as justified in order to nurture a “civilized” and honorable form of speech. Thus, the official repertoires of legitimate media speech were not simply unilaterally imposed: they were negotiated and agreed upon by some dominant journalists within the media field.

Journalists from the New Vision, the Weekly Topic, or the Monitor were sometimes very critical of what they saw as grave excesses of power. But in the first ten years of the regime, they still accepted the premises of the new political order Museveni was trying to build after the “revolution,” and they were clearly dominating the market, which put them in an excellent position to lead the debate on what “professional” or “legitimate” journalism was. The way they reacted to the first operations of repression against some newspapers in 1986 and 1987 is revealing. Beyond the political issues at stake (consolidating the new political order after a bloody war), their concern was also clearly the restrictive definition of a profession, of what “real journalism” was. In their eyes, this was necessary to consolidate their position, including toward the state. According to William Pike, editor in chief of the New Vision: “Government was heavy-handed but it was often provoked. Even Amnesty International said that most of the cases had arisen ‘because journalists have written wildly inaccurate stories without making proper efforts to check their facts.’”36 James Tumusiime, his assistant in the mid-1980s, agreed: “They were blackmailing, it was gutter press, yellow press, different people. Serious newspapers survived.”37 Wafula Oguttu, who edited the Weekly Topic and later the Monitor, had a similar opinion: “They were just small secessional [sic] newspapers [. . .] writing inflaming stories which are not even well researched, making a rumor very, very big. [. . .] They were people who thought they could make a little money. Some of them were not even journalists.”38

Journalists position themselves not only politically, but also as a profession, and as members of particular social groups. Even in a politically restricted configuration, everything that happens within the media cannot be exclusively attributed to the state and its hegemonic agenda: parallel dynamics, linked to the nature of the media as a field, need to be taken into account. This is well illustrated by the process that led to the adoption of the 1995 Press and Journalist Act, which was also the result of the mobilization of journalists who were close to academia and themselves highly educated. This act embodies the attempt by government to delimit a legitimate public sphere restricted to “professionals” (defined in terms of their level of education), and attempts by particular journalists to impose themselves and their definition of “true journalism” within the field. The 1995 act in fact expresses a coincidence of objectives of control and criticism that was not necessarily conscious or voluntary.39 The way control over discourse is enacted cannot be reduced to state constraint and repression: side dynamics and autonomous issues were at work, too, linked in this case to professional recognition and the need to be taken into account.

As a member of the profession recalled, “Many veteran journalists linked the creation of the journalism course at university to President Museveni’s despise for journalists’ bad training at that time, [and to] his anger against what he saw as looseness associated to an absence of proper training.”40 Indeed, during a press conference in 1990, Museveni famously called journalists “former fishmongers” who had “abandoned their nets” to go into journalism. The endeavor by some to strengthen media speech by linking it to academia was reflected in the 1988 creation of the Department of Mass Communication at Makerere University and in the 1995 Press and Journalist Act, which was aimed at turning former “fishmongers” into properly qualified professionals. The act defines who is a journalist (and thus who can publish in a newspaper or speak on radio) based on academic qualifications.41 As mentioned before, despite the fact that it is sometimes presented by human rights organizations as being hostile to “freedom of speech,” the act was partly the result of a mobilization by journalists themselves. It was not, however, consensual. A journalist remembers the “perpetual argument of whether to push for professionalization of journalism in the line of law and medicine or let [in] anyone who can just practice the trade of recounting stories.”42 Was speech to be let loose? In the opinion of those who defended the law, the act would strengthen their political position by fundamentally distinguishing them from the people who worked in the partisan or religious press, who sometimes defended agendas qualified as “sectarian” (and as “nonprofessional”) by the political authorities and dominant journalists themselves.43

Things have changed for the press in Uganda today. But going back to these controversies was necessary to understand that when interactive radio started to be programmed on private airwaves in the mid-1990s, these shows challenged the established repertoires in the definition of legitimate media speech. For not only the government but for many people, talk shows in general, and the ebimeeza in particular, represented the terrible perspective of speech let loose: of laypeople, not professional journalists, taking control of the airwaves. In this sense, they challenged both previous compromises on the nature of media speech and previously established models of citizenship.

Exploring Imaginaries of Citizenship as Products of Relations of Domination

The ebimeeza have often been referred to in the scholarship on the media in Uganda, but they have never been the focus of in-depth ethnographic and historicized research.44 The richest study available on interactive radio in Uganda more generally is Peter Mwesige’s work, which relies on a very large corpus of shows and interviews with members of the audience, including from several ebimeeza. The issues raised by Mwesige in his research are, however, different from those examined here. His concerns have to do with the potential of talk radio to enhance public debate and democracy. He examines the capacity of these programs to integrate better the concerns of the public into the media and into the political agenda, to offer participatory opportunities beyond “a socially advantaged minority,” and to enhance pluralism.45 One of his main research questions concerns the elaboration of the “political talk show agenda”: What topics are tackled? How are they determined, by whom, and what room does this leave for popular concerns to be raised? He found the overall talk show agenda to be linked to, but not dependent on, the government’s agenda. He also showed that there was a clear discrepancy between the talk show agenda and the concerns of the wider public, as defined by national surveys (people seemed more concerned with issues such as poverty, HIV, education, etc.).46 In terms of the political influence of talk shows, he found that it was very limited. Mwesige concludes that even if they did not favor “genuine” participation, interactive radio programs did allow for a greater degree of elite competition and did strengthen pluralism, especially in a politically restricted environment.47 He explains that “some ordinary voices have access through opportunities of audience participation, but they are easily drowned out by the political elites whose ‘expertise’ still appears to reign supreme. [. . .] While political talk shows facilitate some degree of political contestation and citizen participation they come off as an imperfect public sphere that is characterized by participation inequality.”48

For my part, I refrain in this particular book from reflecting on whether the ebimeeza were actually representative of the “public” or not, or whether they enhanced “democracy.”49 However legitimate and important these questions are,50 I argue that the varied conceptual frameworks brought together by democratic theory carry the risk of not doing justice to a very rich and historically situated phenomenon, by forcing upon it univocal, historically situated and normative grids of interpretation.51 The ebimeeza provide a heuristic entry point to unearth the historicity of entrenched emic debates about the conditions of political participation and belonging in Uganda. What I seek in this book is to allow these emic representations of the legitimacy “to speak out,” to emerge from the field. This avoids the risk of casting them aside because they may be “undemocratic.” I want to understand how certain features—often considered as flaws—are interpreted and sometimes valued by people themselves. I want to see what they reveal of the Ugandan political game; what they mean in a given historical context; and how they reflect particular, historically grounded political and social cultures. This should also help us understand the forms speech took in the ebimeeza.

Adopting an evaluative and normative framework does not encourage asking questions about what kind of political, social, and civic heritages surfaced during the ebimeeza or were nourished by them. It is necessary to reconstitute carefully how the ebimeeza made sense, in varying ways, for different people and organizations (political parties, NGOs, the Kingdom of Buganda), how they were integrated into their social trajectories and ambitions, and how all of this influenced the ways the debates were organized. Such an analysis will also allow particular features of the Ugandan political game and society to be highlighted. Many people in Uganda criticized the fact that some orators were encouraged to participate by political parties, which supposedly jeopardized “the viability of talk shows as avenues of civic engagement.”52 I argue that such concerns should not prevent us from studying these dynamics in order to illuminate further the functioning of political parties in Uganda and their social composition. The incredible display of self-confidence from orators, their particular forms of speaking, and the quasi-professionalization of some are extremely significant in regard to Uganda’s political and social history. As we will see in detail, the concerns raised by the ebimeeza were structured by much older debates, in Uganda in general and in Buganda in particular, about who is entitled to speak in public, and they allow unearthing the daily workings of electoral politics and the localized effects of the transnational political economy of development in renewed ways.

The social embeddedness and the more or less intended effects of radio in the creation of cultures, in the coming together of communities and the imagination of social persons, have been the object of fertile research in African Studies. Researchers have sought to understand the intentions of the colonial state in using broadcast technologies,53 and also to analyze how, in complex ways and through its vernacular appropriations, radio has enabled sensitive experiences of modernity, which have been both enslaving and liberating.54 Radio has also offered a platform for particular sections of colonial societies to voice their social ambitions and craft their own languages in relatively autonomous ways.55 African broadcast cultures, even at their most local and chauvinistic, are nodes of cosmopolitan encounters and cultural hybridity.56 Radio has often been used as a way to affirm a connection to the world and to claim power in the name of cosmopolitanism.57 African broadcast cultures have enabled creative new spiritualities and religious authorities to emerge.58 They have provided and contributed in the forming of spaces of gendered moral guidance, patriotic nostalgia, and resistance;59 they have challenged or entrenched established divisions between public and private.60 Lately, African radio programs have also offered fertile ground on which to analyze particular figures of moral authority and explore local conceptions of justice and truth that are often overshadowed by hegemonic transnational narratives of human rights and free speech.61

By uncovering, through the study of the ebimeeza, local yet globally connected debates about suitable ways to engage in politics, this book aims to contribute to this growing field of research. I seek, however, to examine, in possibly a more direct way than has been done before in African radio studies, the close interactions between radio and political power: to bring the state and politics “back in.”62 The idea is to document the daily making of radio speech at the crossroads of a variety of social dynamics, but also in relation with the working of the state as a heterogeneous and changing space, in relation with electoral politics and within local power configurations. Eventually, the objective is to understand how speech is the result of a politics of control, but in less straightforward ways than what might have been expected in a “semiauthoritarian” regime.

To examine these issues, the analysis here relies on fieldwork carried out in Uganda (mainly in Kampala, but also in Fort Portal, Gulu, and Masaka) between 2005 and 2013. This fieldwork linked the systematic observation of dozens of ebimeeza programs with in-depth and sometimes repeated biographical interviews with orators, spectators, organizers of the ebimeeza, politicians (especially members of Parliament), state officials in charge of communication, officials from the Kingdom of Buganda, advertisers, journalists and radio producers, NGO staff, media managers and owners, and so forth. In total, more than 150 persons were interviewed, and a questionnaire was distributed during three different ebimeeza. The fieldwork also provided material based on the observation of meetings of orators’ associations; in-depth content analysis of twelve shows transcribed into English and translated from Luganda and Lutooro (as well as listening to dozens of others); the examination of the archives of two of the ebimeeza made up of hundreds of lists of orators, members’ notes, and documents produced by the organizing committees (such as meeting reports, correspondence with members, etc.); and finally the analysis of local press articles and letters to the editor on the ebimeeza.

This material reveals not only how people talked, but also the historically and socially situated ways people had of imagining good forms of speech. These representations were at the center of heated debates and controversies on the ground: Who was entitled to speak and how, about what, from where, and according to what rules? The varied answers people have given to these questions provide information about deeply entrenched conceptions of political personhood and political order. These conceptions need to be historicized and situated socially. Social actors did not have the same capacity to impose their views on who could speak and how. The state, in particular, displayed a special urge in trying to impose its vision of legitimate speech, of the delimitation of what should be said and what should not. But, as we will see, the state was not alone in this.

Many authors before have used practices of discussion to decipher emic conceptions of good government, civility, and morality, and have underlined how local forms of sociability are fruitful cradles of imaginary polities. Collective places of leisure—pubs, clubs, cafés, salons, tea meetings (called addas in India and grins in West Africa), the baraza of Zanzibar, and upper-class clubs in Kenya—have indeed historically been the framework of conservative or innovative solidarities and political ideas, in a more or less intentional way.63 Maurice Agulhon and Edward Thompson in particular emphasized the links between the transformations of sociability practices and the larger evolutions of political culture in eighteenth-century and nineteenth-century France and Britain. There, the creation of “circles,” religious societies, and constitutional clubs opened the way to creating an ethos of equality.64 Many such examples have existed at different times in history.65

Eventually, the underlying question raised in this book has to do with the controversial and emic partitions made by varied people in contemporary Uganda about what can be talked about out loud, and what cannot. This controversial question is particularly relevant in the case of Uganda, given its centrality in the political and religious history of the country.66 But the limits of speech—about what can be said and what cannot—have also been key issues in more recent events and dynamics: the social and economic importance of the so-called “yellow press”;67 the heated controversies around the question of sexual behaviors and preferences;68 and the harsh repression of anthropologist Stella Nyanzi (who researches precisely the injunctions weighing on women’s and men’s speech and behavior in the name of gender conformity).69 Such issues raise tragic and fascinating questions concerning the violent emic negotiations on the borders of the “public sphere.” As Michael Warner has emphasized, the great and controversial partition between the “public” and the “private” realms has been a canvas for thinking about the possibilities of emancipation in Western political thought, while also being a reflection of gendered relations of domination.70

The other reason why this project might be all the more relevant in the Ugandan context is that citizenship and the ways of thinking about oneself as a member of the polity have been at the center of strong reform efforts by the NRM government. For the last twenty years, a relatively open and nonnormative definition of citizenship has been adopted in African Studies.71 It relies on empirically based, inductive approaches that take into account but also go beyond questions of legal status. Citizenship in this context is understood as the emic and plural notions that form the basis for the imagination of sovereignty, participation, and access to certain rights and belonging. This wide definition allows for the investigation of the varying ways in which people conceptualize belonging, the borders of the political community, their rights and duties and those of others, their relationship to political leaders and to the state (what do I owe to the state and what does the state owe me?). It also covers the forms and repertoires of political engagement people might have with it.72 Scholars have been analyzing who people consider to be citizens, the social and moral arguments at play in the changing definitions of who is “in” and who is not, and who is a “better” citizen and why. They have underlined the variety, richness, rootedness, and cosmopolitan character of African political thought on these subjects.73 A number of scholars have, in particular, contested clear-cut dichotomies in terms of citizens versus subjects that do not cover the “patchwork of legal statuses” in existence in Africa,74 in the past and present. Neither do such dichotomies encompass the intertwinement of claims of sovereignty and submission (the latter being far from equivalent to passivity).75 Scholars have noted the diversity of spheres of belonging or engagement, the plurality of the actual practices and the representations at play on the ground, as well as the varieties of pasts and futures people refer to.76 This book builds on this very rich literature, but insists on the fact that the study of these conceptions cannot be isolated from the mechanisms of social and political domination in which they take part.

As mentioned, the invention of a particular format of citizenship has been at the center of strong efforts by the NRM government. During the Bush War that led him to power (1981–1986), and influenced by Nyerere’s Ujamaa and Maoism, Museveni crafted the model of the “Movement democracy.” This model is grounded in a universal belonging to the NRM (seen as being equivalent to the Ugandan citizenship); regular elections based on individual merit and not party tickets;77 and the creation of participatory structures at the grassroots level, namely, the Resistance Councils (RCs).78

According to Museveni, political modernity can be reached only by annihilating the mechanisms that favor the permanence of “archaic” features, namely, ethnic and religious sectarianism. By parting with primary solidarities that cloud judgment and lead to making irrational political decisions based on identity, citizens could make choices favoring development.79 Museveni believes that “ethnicity and sectarianism [. . .] are short term problems”80 that will be overcome through commerce, education, work, and a nonpartisan form of collective mobilization.

One of the main vehicles for the emergence of this renewed society was the institutionalization of a system of “grassroots democracy,” incarnated by the Resistance Councils, today called Local Councils (LCs). The smaller units (RC1s and LC1s), which correspond to the village levels (or “zones” in urban areas), are open to anyone age eighteen and above.81 Citizenship as mediated by the RCs is based on residence,82 and transcends ethnic, party, and religious affiliations.83 The RC system was more or less successful, depending on the region.84 Whereas they were spheres of political mobilization and education during the war, they were then transferred under the authority of the Ministry of Local Government and refocused on local issues, typically managing security and public works issues. RCs also act as a channel between the government and the local populations.85 Attendance at meetings has become more uncertain with time, and RCs have not always managed to overcome older established social hierarchies.86 Despite these limitations, many have acknowledged the fact that the councils have been widely invested and appropriated by Uganda’s population, sometimes with great enthusiasm, in particular in the South of the country. Moreover, RCs saw their mandate enlarged for a few years at the beginning of the 1990s, as they were used as local arenas of mobilization and discussion of the new constitution project.87 Generally, scholars agree that they led to important mutations in people’s and local leaders’ political practices and conceptions of political legitimacy, of citizens’ roles, and of the relationships between rulers and ruled.

Generally speaking, with the advent of the Local Councils, political participation and social mobilization were strongly encouraged by the authorities to take place within the state structures, or at least according to the Movementist repertoires of mobilization.88 Nevertheless, this move toward a relatively domesticated format of political participation was not necessarily based on constraint. Women’s organizations in particular initially adhered largely to the social and political project of the NRM.89 The situation was different, however, for actors who were stigmatized by the NRM project, especially the kingdoms. In 1993, Museveni overcame his own reticence and accepted the restoration of the monarchies that had been banned by Milton Obote in 1967.90 But this was done only under certain conditions, as the kingdoms did not recover all the prerogatives they’d had at independence. According to Article 246 of the 1995 constitution, a “cultural” or “traditional” leader should not get involved in “party politics.” “Involvement” in “party politics” is difficult to delimitate precisely, but this ban is often interpreted broadly by state officials, and clearly restricts the ways in which people are allowed to be involved in the discussion of common issues. This question has been particularly heated in the case of the Buganda Kingdom,91 and the ebimeeza found themselves at the center of this controversy. As historians have shown, Buganda has been the cradle of intense conversations about good ways to be a citizen, a subject, and a good Muganda. 92

Study of the ebimeeza also provides an opportunity to explore current forms of Ganda patriotism, conceptions of belonging and how they are intertwined with alternative sources of the imagination of the self, and civic virtue. More generally, in such a context of ideological pluralism, questions remain as to the ways people see themselves as members of the polity, decades after the “revolution” that led Museveni to power. By studying the ways in which people speak in public, and the ways people think one ought to speak in public, this book will help to unveil the composite and fundamentally political character of the imagination of political personhood in contemporary Uganda.