Читать книгу Talkative Polity - Florence Brisset-Foucault - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеONE

The Ebimeeza and the Political Culture of Kampala’s Upper Class

“IT IS THE COMMON PEOPLE [WHO COME]. THE EVERYDAY MAN and woman that you meet on the street. [. . .] Day-to-day people, the common man comes around, expresses himself freely.”1 This is how one of the first producers of Ekimeeza introduced me to the show when I first went to Kampala in 2005. In day-to-day conversations and in the media, the ebimeeza were indeed often described as popular spheres of discussion, where “ordinary citizens” could come and air their views.

The ebimeeza emerged, however, within a very restricted social circle, and were originally imagined as the fulcrum of a culture of distinction. Actually, what characterized them was their plasticity: the fact that people used them to promote very diverse models of citizenship and political culture. This tension between the imagination of a high-quality debate among men of culture on the one hand, and popular democracy on the other, marked the ebimeeza from their inception until the 2009 ban. This tension was constantly debated, never actually clarified, and was at the core of the state’s ambivalent attitude toward the talk shows. Actually, the question of whether or not the ebimeeza should be opened to the masses had important implications within the emic debate on the nature of democracy in Uganda, and involved deeply antagonistic imaginaries of citizenship.

The first ekimeeza to be launched was held in English and resulted from the broadcast of discussions held among a group of friends who used to gather in one of Kampala’s famous clubs, Club Obbligato. The ebimeeza thus need to be resituated within a particular history of sociability practices, and in the trajectory of a specific group: the Ganda business class. A close reconstitution of their emergence shows how these new possibilities to take the floor and express oneself were not the result of radical struggles for “freedom of speech” or for the participation of “the common man” in politics. Instead, they were linked to a history of interelite relations within the political, economic, and social establishments. The study of the ebimeeza thus allows for the genesis and social grounding of the Movement State to be revisited and enables going against the grain of the official historiography that portrays it as the result of a univocal “social revolution” that gave back power to the grassroots.

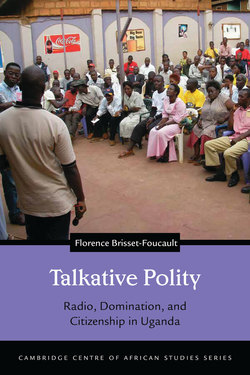

FIGURE 1.1. Opinion piece by David Ouma, “Bimeeza Took Debate Down to the People,” Monitor, 24 January 2003, p. 8.

Over time, however, the social perimeter of the discussions was enlarged to other ethnic and social groups, particularly, but not exclusively, through the creation of new shows in Luganda. A new generation of orators emerged, although this did not emancipate the ebimeeza from the bourgeois context that led to their initial development.

An Upper-Class Cradle

The history of the ebimeeza is linked to a particular place in Kampala—Club Obbligato—which was located in Industrial Area, a mile away from the city center. The club comprised a vast courtyard, with a bar, a stage, and a large thatched roof covering a pool table. Three businessmen purchased the premises in 2000.2 The group then approached Afrigo Limited, headed by Moses Matovu and James Wasula, who managed Afrigo Band, one of Uganda’s oldest and most famous musical groups, to propose that the performers settle in at Obbligato and perform there regularly. The three purchasers and Afrigo Limited formed a partnership and managed the club together.3 Led by Moses Matovu, a percussionist and saxophone player born in 1950, Afrigo Band was created in 1975 and has produced around twenty albums of Afro-beat and rumba music.4 The group became famous after they were hired by Idi Amin to perform during his luxurious parties.5

FIGURE 1.2. Club Obbligato in Kampala, 2007. (Photo by author.)

FIGURE 1.3. Ekimeeza audience #1 at Club Obbligato, 2007. (Photo by author.)

When I was in Kampala, attending a concert cost USh7,000, which was prohibitive for the majority of the population. At the concerts I attended, the club was full and the majority of the people were men over forty, because of the entry price and also the musical style. It was often possible to spot famous political personalities at concerts, such as Nyombi Thembo (minister in charge of Luweero Triangle, and later on minister for information communications technology); Brig. Kasirye Ggwanga;6 and even Salim Saleh, President Museveni’s half brother, who “pop[ped] in and [did] the entole dance.”7 According to a journalist, “In this rich man’s entertainment spot, patrons are generous like their ancestors were during the harvest season. There is Jomayi, a popular purse happy man [Jomayi Consultants is a real estate agency]. When a business deal is successful or when his football team wins, expect free beers on him all night long.”8 During the day, clients might find a well-stocked buffet with typical Ganda food for USh7,000 (around £2, which is relatively expensive in Kampala). Thus, many members of the clientele were part of the wealthy upper class, with connections to the political establishment.

FIGURE 1.4. Ekimeeza audience #2 at Club Obbligato, 2007. (Photo by author.)

As one of the owners of the club, James Wasula, told me: “[In 2000] it was a new place; [we wanted] to attract our friends and meet us at that place, to build a clientele.” 9 One of the owners’ friends, Alan Shonubi, recalls: “[Wamala] wanted to launch his business [. . .] and in order to get more people, he started to give out some free lunch, and [. . .] as a result we started talking and then you know we choose a topic and talk about it.”10 These discussions eventually became the Ekimeeza weekly broadcast.

The first participants in the debates at Club Obbligato, those who were there before the radio began to broadcast the discussions, were called the “historicals” by the other members of the ekimeeza. By tracing the “constitutive networks” that led to the emergence of this small group of people,11 it is clearly possible to see how the first ekimeeza prolonged sociability practices typical of a certain section of the Ganda elite: the corporate businesspeople who managed to protect their assets and status relatively well during the years of dictatorship and were ready to invest (financially and politically) in the reconstruction of the new state under Museveni.12

Among them was for instance Paul Mbalali Wamala, the owner of the club. He was born in 1950 into an affluent Ganda family.13 His maternal grandfather was Simeoni Nsibambi, a wealthy landowner and member of the kabaka’s government who was considered one of the founders of the Balokole, the Ugandan Pentecostal Christians.14 Paul Wamala’s father, Dr. Paulo Wamala, owned a pharmacy and a large hotel by Lake Victoria. He was close to Kabaka Muteesa II, and Paul Wamala says that Paulo helped the king during the 1966 crisis, when the kingdom was attacked by Obote’s government.15 Paulo Wamala was killed under Amin’s regime. After his father’s death, Paul Wamala graduated with a business administration degree in Britain. In 1986, when Museveni came to power, Wamala got part of his father’s property back. When we met, he operated in construction, real estate, and entertainment businesses. Thanks to his family history, Wamala claimed that he “talk[ed] with the king every week,” but he was critical of the radicalization of royalism that occurred in the mid-2000s. He also had close contacts with members of the NRM government, especially for business reasons.16

Another important historical was James Wasula, who was born in Mengo, in the heart of Buganda, at the end of the 1950s.17 His father worked for the kingdom in the Lubiiri, the royal palace, while his mother worked at the Ministry of Finance in the central government. Wasula went to primary school in the palace. When it was attacked in 1966, he fled in one of the kabaka’s vehicles. His father then entered the Ministry of Education of the central government. After passing his A levels, Wasula worked at the high court, then studied in South Africa. Back in Kampala, he specialized in accounting and joined the Coffee Marketing Board, staying in that position until its privatization in 1991. Today, Wasula works in intellectual property and the protection of copyright. He is a musician and has managed the Afrigo Band since the 1980s. In 2000, he bought shares in Club Obbligato. He was the main chairman of the Ekimeeza until it was banned in 2009.

However, before Wasula assumed the chair, the first chairman of the Ekimeeza was Alan Shonubi, a lawyer born in 1958.18 He is also from a wealthy family connected to the kingdom’s establishment. His grandfather was a chief and attended King’s College Budo, the “jewel” of Uganda’s colonial education system, created in 1906 and following closely the model of British public schools.19 His mother, Catherine Senkatuka, was a well-educated Ganda woman. She also went to Budo, and in 1944, she became the first woman to be admitted to Makerere College.20 In the 1950s, she went to study in Great Britain. According to her son, she was also a member of the Legislative Council (LEGCO), the Ugandan parliament before independence. She then became a secondary school teacher. Alan’s father is a Nigerian businessman. Alan Shonubi followed the family path and also went to Budo. He then entered the prestigious Law Development Centre (LDC) in Makerere for the necessary schooling to become a lawyer. Nevertheless, it was difficult to find a position during the war. As a musician, he performed in bars in Kampala, and that was how he came to meet the Afrigo Band. After the war, in 1986, he worked in insurance companies and in a bank, before creating his own bank. Since 1990, he has headed a law firm, Shonubi, Musoke & Co. Advocates, which specializes in corporate law and employs ten lawyers. He was said to be one of the richest men in the country.21 He sent his three sons to Budo, and in 2005, he chaired the Old Budonians’ Club, after having been the vice-chair for seven years. As he told me, “I transformed the club. It was a paper organization earning a few hundred thousand shillings per month [around £30] to cover its activities. Today it has a [USh]36 million budget per year [around £13,000].” In 2005, he also joined the board of the school.22

Another historical was Edward Kayondo, a medical doctor born in 1955, near Kampala.23 When we met he was the president of the Old Budonians. He grew up in Bulange, close to the kingdom’s seat. He is from a more modest extraction compared to Wasula, Shonubi, and Wamala. His father was a medical officer. According to one of their friends, Kayondo was the only one among the group who had to “make himself on his own” through education.24 He went to the Mengo boys’ school and then to Budo, thanks to a grant he received because his grandfather was a priest and had been to Budo in the 1920s. In Budo, he met Betty Kamya and Winnie Byanyima, future MPs and political celebrities, as well as Crispus Kiyonga, the future minister of defense. He also met Alan Shonubi. In 1973, he became secretary-general of the school’s debate society. He entered Makerere in 1974 where he studied medicine, and then he went for further studies in Newcastle, leaving there to travel around Europe and the United States. In 1982 he went back to Uganda where he taught medicine. He owns land, a school, and a hotel. For a few years, he compiled and published almanacs and books about the most important educational establishments of the country.25 He sent five of his children to school in Budo.26 Edward Kayondo never missed the Ekimeeza radio talk show, of which he was an emblematic figure, sometimes chairing the debates.

It was striking that these men were a product of the diversification of the Ganda upper class and the attenuation of its fragmentation between landowners, businessmen, and professionals, which occurred during late colonialism.27 Some of the historicals inherited social status through land and relatively important positions within the kingdom’s administration, but their parents and they themselves founded their social standing on a combination of business, education, and the professional world, including positions within central government. This mutation allowed them to reconstitute their status after the turmoil of the 1960s and 1970s, the impoverishment of tenants, the nationalization of land, the disappearance of the kingdom, and the crumbling of the economy.

The extent to which the social status of the historicals influenced their position toward Movementism and royalism will be analyzed further below. But it is necessary to underline here that the historicals knew one another well prior to the emergence of the Ekimeeza. The four men introduced above were part of a larger group of childhood friends who participated more or less intensely in the discussions. For some of them, these links were reinforced by family connections. They all stayed in Mengo, and some of them had close connections with the royal establishment. Several of them met at the Mengo boys’ school or Budo. Later, they engaged in business together, in particular in the entertainment and land and housing real estate sectors. Some of them, especially Paul Wamala, were already acquainted with Maria Kiwanuka, the owner of Radio One, who was from an important Ganda family and a prominent figure of the Kampala business community, and later became minister of finance (see chapter 2).

These men brought a specific kind of political and social heritage to the Ekimeeza. Their practices of sociability were strongly illustrative of particular educated and masculine ideals of “modernity” and social distinction, linked to Kampala’s multiethnic professional and business urban environment.

A Bourgeois Masculine and Individualistic Sociability

Sociability encompasses practices that are objectively determined but subjectively discerned as governed by affinity.28 They are specific to particular groups and thus often discriminative. They need to be learned, require special know-how and skills, and their preservation can be linked to ambitions of sociopolitical domination and ethnic, gender, class, or state formation.29 For reasons explored below, important members of the original group of friends left the Ekimeeza at Club Obbligato. However, they continued to meet regularly (for some of them almost every day) in another pub, Club Magic, also owned by Paul Wamala.30 Therefore, Club Magic was a good place to observe the way they interacted and reconstitute the atmosphere of the first discussions that gave birth to the ebimeeza.

Club Magic was located in the center of Kampala, near the central avenue, Kampala Road. It was both a restaurant and a car park. Like most capital cities, Kampala is greatly affected by traffic jams. Members of the upper class are reluctant to use public transport or mototaxis (boda boda), and often complain about how difficult and unsafe it is to park in town. Several people explained during interviews how they selected their leisure activities based on parking criteria: the Magic Club was an answer to that dilemma. As with Club Obbligato, lunch was expensive (USh10,000, around £4). Beyond considerations of practicality and comfort, bars are obviously strong markers of social distinction. A regular orator, also a client of another of Kampala’s famous drinking places (the Lugogo Rugby Club) and himself an Acholi, once explained to me that one could find “the cream of the young Acholi intellectuals” in Lugogo.31 He also explained that “finding a proper lunch in Kampala is very difficult. . . . There are many places to eat but to call that a lunch . . . [At Club Obbligato at least], we didn’t have to choose between chicken and meat.”32

According to informants, the meetings in Club Magic were quite similar to the original ones in Club Obbligato; they harbored a very different format of sociability than the formality that characterizes family and clan ceremonies in Buganda, which are usually very hierarchical, marked by congregating around the “guests of honor,” and by deference toward elders. Such gatherings aim at strengthening the links between members of a clan or restaging family roles.33 As Mikael Karlström noted, clan meetings are the cradle of an exclusive format of sociability, which nourishes social hierarchies and thus promotes a specific model of personhood rooted in clan genealogy and defined by one’s place in the clan social fabric.34 In Club Magic, the sociability was largely masculine. It was very rare to meet wives and children, and as one interviewee explained, it would not come to members’ minds to bring relatives.35 The rare women who came did not come as wives but on their own. As we will see more precisely below, the absence of women had an important influence on the format of the ebimeeza. Their absence also distinguished the shows from other kinds of gatherings, in particular the Local Councils and church meetings, as well as the rural and up-country talk shows, where the presence of women, and also children, was important. Meetings in Club Magic, as was originally the case at Club Obbligato, were the cradle of an exclusive equality among men of a certain standing.

The following quotation by Dr. Edward Kayondo, talking about Club Obbligato, illustrates the specificity of this format of sociability and how it was seen by the historicals:

Q: Why this pub in particular? What did it have that was particular that people would meet there?

A: Well, it was out of town, slightly out of town, with parking, quieter than town, it had a band after. After discussion we could go dancing all night. . . . It had cooking facilities.

Q: Why was it important that it was out of town?

A: Because in town you have no parking. And you have noise, and you don’t have such a big area. . . . And the people running it are friends. . . . This place is a social club.36

The word club, as used by Kayondo, was ambiguous, referring not only to the idea of a nightclub but also to “social clubs,” which were typical of colonial sociability and as such implied an idea of exclusivity and an ambition to be part of the social and cultural elite.37 Contrary to the latter, Club Obbligato was not officially exclusive: one did not need to be registered as a member to get in. That principle was not evident at the beginning, though; some founding members of the Ekimeeza would have preferred to preserve a certain exclusivity or privacy. However, as the lunch meetings were not protected by any rules or open financial barriers, and because of the commercial objectives of the club’s owners, who wanted to attract the most people possible, the entre-soi started fading, especially after discussions began to be broadcast.

Distinguished Movementism

Such ways of being together were strongly related to the forms of political action these actors valued, to their political ideals, and to the ways they interacted with the state and political elites. The following quote from an interview with two historicals illustrates their state of mind:

Historical #1: [Under Amin], when you had a car like this one [a 4x4], they took it from you like that. You were killed and they drove it without even changing the number [plate]. . . . Wamala’s father was killed because of his property. If he hadn’t been rich, maybe he would still be alive. But he died because of his money. So why would I want politics? Let [Museveni] be in power as much as he wants, if we are at peace . . .

Historical #2: We didn’t think it would turn out like this, but [Museveni] brought change. A big change . . . [Now] you can make money and you can drive as many cars as you want.38

These actors were very attached to a certain kind of political and economical liberalism. They did support Museveni, but not because of any partiality toward the “grassroots democracy” institutions and mythology that are at the core of the NRM discourse and project. Far from being militants or even adhering to the NRM’s political philosophy, these men’s opinions illustrate the position of a large part of the Ganda elite of the 1980s who, as Mikael Karlström said, were “hoping when the NRM came to power in 1986, for a more benign political order and an economic climate which would allow them to reconstitute their class position.”39 And indeed, the faction of the Ganda elite engaged in industrial and business activities benefited quickly from the regime change, especially the ones who chose to cultivate close ties with the new leadership.40

The historicals qualified their actions and political preferences as “apolitical” and were very reluctant to turn these preferences into open support. They manifested their political opinions through individual micropractices of sociability, such as private meetings, and the Ekimeeza was clearly seen as an extension of this. As one of them explained:

[Thanks to the Ekimeeza], people have really seen who were the Salehs [president’s half brother], that they could be approached. . . . I think it really helped us politically. Even if I am not engaged in politics.

Q: What do you mean when you say “us”?

A: I mean the Movement. I don’t want to say that I am not a Movement man, even if I am not engaged in politics. Because I am behind the Movement. I am behind Museveni. Because of the experience I had in Obote’s time, in Amin’s time. I saw a big change and I appreciate it. [. . .] I don’t have money to put in politics, but I campaign for them. [. . .] I inform people. I talk for them in private circles.41

Founding members preferred intellectual and discreet ways of engaging in politics, and some tried, for example, to promote a dialogue between the central government and Mengo behind the scenes, which recalled the forms of engagement used by the Ganda conservative elite under the protectorate.42 According to the Ekimeeza historicals, political relations had to remain a private affair, anchored in sociability and paradoxically defined as “apolitical.” The decision to broadcast the discussions was thus criticized by some because it broke this discreet pattern of political involvement.

For the historicals, being a “Movement man” while “not being engaged in politics” was not contradictory. Generally speaking, founding members of the Ekimeeza had very few political experiences in their youth. Contrary to other portions of the Buganda elite or aspiring elite, they had not supported the Bush War and were even less engaged in it.43 Some supported the NRM financially, as many businessmen do in Kampala. But once again, they did not define this as something “political,” as one explained:

I got what I wanted, which was peace. [. . .] I went out of politics. Apart from supporting the NRM when there’s fund-raising, but apart from that I am just a [professional] and a businessman.

Q: But still you give some money . . .

A: To the party yes, if I can, I do.

Q: You are an official member of the party?

A: I am not, but I am a supporter of the party. I don’t have any cons. For me, my aim was to have peace. Peace that would do to make a better country for my children, my children to be happy. You know, before, you could not have a building like this with just glass [he waves toward a huge skyscraper]. You need to have ugly [concrete] . . . so for me, what is here is a good thing.44

The Ekimeeza was born out of the attachment to intellectual political debate rather than radical ideals of democracy. It had nothing to do with the model of the Resistance Councils, in which these men were not interested.45 In a certain way, the beginnings of Ekimeeza reflected an ideal of a bourgeois liberal public sphere and a desire to be distinguished from the citizenship promoted by the Movement.

These men’s moderate position toward Ganda royalism should also be noted, and can again be better understood by taking into account their socioeconomic status and trajectories. The historicals considered they had benefited from the change of regime and did not come from radical royalist family backgrounds. They did not see their social and moral fulfillment as being ontologically linked with the restoration of the kingdom. Their attachment, in some cases, to the institution of kingship and to the king in person did not encourage any support for the radical royalist politics of the 1990s and the 2000s, but led instead to a desire to act as intermediaries and to protect a certain social and economical stability, in accordance with their discreet comprehension of political action.

Nor were they champions of multipartyism. As a matter of fact, the historicals’ attachment to the Movement system also came from their own strong hostility to party politics. Their position reflects how Museveni’s leftist historical diagnosis of the necessity of avoiding political parties on the count that African societies were not divided along class lines was amalgamated with an elitist hostility to mass party politics seen as vulgar and perilous.46 For these highly educated men, the absence of party politics was regarded as a condition for a sane and high-quality debate, based on personal ideas rather than party discipline or ethnic and religious identities. Their hostility to party politics was intertwined with an ideal of political engagement that had to be very light, discreet, and intellectual, and that thus diverged from the “official” Movement ideology. This was reflected in the comments the historicals made on the new generations of Ekimeeza speakers, whom they often accused of “politicizing” excessively the topics of discussion. As James Wasula explained:

I don’t like [political] parties. They tend to oppose anything, so whatever topic you bring they will be on the opposition. It’s funny—I don’t know how it happens, but that’s how it happens.

Q: It also depends on how you write the question, actually—

A: No. It’s so funny. [. . .] There was a topic on football and people who would not support were all from the opposition.

Q: Didn’t support what?

A: You know, there was [. . .] a committee which was administering the administration of football in Uganda, so we wanted to talk about football and actually the invited guests were mainly from the football fraternity. But the few that participated from Ekimeeza, those who opposed the topic, were from the opposition. And it had nothing to do with politics (he laughs).47

The “partisanization”48 of the Ekimeeza was regretted and associated with sterile debate, emotionality, and lack of content. For the historicals, on the contrary, not being in a party reflected a certain political sophistication and independence of mind, and the fact that the opinions expressed were based on the strength of arguments rather than political discipline. Political competition and antagonisms, however, were far from absent from the Ekimeeza, as we will see in detail in the next chapters.

The Social Composition of Ebimeeza Audiences

As mentioned, founding members invited their famous friends to attend the discussions. This was an extension of their usual social and political practices and ensured the maintenance of a certain standing.49 But it was also a commercial strategy. The presence of political celebrities, in particular Capt. Mike Mukula, former minister of health; Tim Lwanga, at that time minister of ethics and integrity; Capt. Francis Babu, former minister of work, housing, and communications; and Nyombi Thembo, minister of the Luwero Triangle, attracted more people.50 Exclusive sociability had thus an ambivalent dimension: high connections were indeed the privilege of a happy few, but the commercial and social value of the Ekimeeza was to make these connections public, and to make more people feel part of the circle.

And indeed, from the end of the year 2000, the audience of the debate enlarged progressively. A new generation of speakers began to attend. They were professional cadres, international corporate organizations, and administration employees, all from different social backgrounds. Among these was L.N., born in 1977 to an Acholi father working in customs. In 2001, he graduated in administration and public management. While a student, he was a member of the executive of the Uganda National Students Association and guild vice president. He worked at the office of the vice president as an assistant coordinator for the National Youth Development Project. He was also an elected member of the National Youth Council, representing a Northern District. He resigned in 2003 because, according to him, it was “turning into a Movement project.” He then went into business and consultancy for the government until he found a position in an international NGO.

Before engaging in the discussions, L.N. frequented Club Obbligato for the good food and the music. He went there with his colleagues from the vice president’s office and had never met the historicals before.51 His participation in the discussions was thus linked to the professional world and the fact that the club was frequented by executives from the administration. However, it reflected more generally a generational, ethnic, and political opening of the Ekimeeza. Supporters of the opposition favoring multipartyism, who had important experiences as student activists and who had only childhood memories of Idi Amin or the Bush War, began to frequent the club. People from Northern Uganda also started to come.

In this context and in the middle of the heated electoral campaign of 2001, Maria Kiwanuka, director of Radio One and one of Wamala’s friends, came to Club Obbligato and attended one of the debates.52 Enthusiastic about the quality of the discussions and looking for a new product to position the station editorially and commercially during the campaign, she asked one of her journalists to “format [the discussions] for radio broadcasting.”53 Sources do not concur on the date of the first broadcast, but it most likely occurred in March 2001,54 between the presidential and the general elections.55 Economic interest is important to explaining the emergence of the Ekimeeza. Wamala overcame his original reluctance to broadcast the discussions: “We agreed [to broadcast] because [the radio station] came with a package. They would give us beers to give to the people who come to discuss. [. . .] We sell [them for] 1,000 shillings instead of 2,000.”56 The Ekimeeza did not generate money in itself: the earnings of the beer sales went directly to the club.57 According to Wasula, the Ekimeeza did not represent a major source of income for Club Obbligato compared to the concerts,58 although it was definitely an opportunity for free advertising.

Even if some among the original members chose to leave, the audience kept growing, in particular in the electoral context. After the historicals and the cadres, students were another population that came to the club: they were mainly men born in the 1970s, most not married and childless, with far more modest incomes. They came in groups, often from campus, after they heard the show on the radio. Again, this audience was diversified ethnically and politically. B.W. and W. K., both members of political parties, from Eastern and Northwestern Uganda, respectively, came at that time.

B.W. was born in 1973 in Mbale.59 He was a Mugisu and a Catholic. His mother was a teacher and his father worked in the administration. He graduated with degrees in education and biology from Makerere, where he led a Hall and was a member of the Panafrican Club, in which he met important leaders of the NRM. He became a teacher, first in a secondary school, then at a private university. He was well known for supporting the NRM and was often teased about it by other members of the Ekimeeza. He was part of the Pan-African Movement, an organization close to the NRM that also organized debates.

W.K. was born in 1978 close to Arua, in the northern province of West Nile. His parents were teachers. In 2005, he graduated with a degree in philosophy. He was president of the guild. He was also an activist in the opposition political party FDC (Forum for Democratic Change) and a member of the Uganda National Students Association (UNSA). He began his political career in 2001 as a political mobilizer in Masindi during Kizza Besigye’s first presidential campaign. When I met him he earned a living thanks to short-term contracts in the information technology sector. For several of the members of this particular generation of speakers, the first contact with the Ekimeeza was through student politics.60

Starting with a dozen people originally, the discussions soon gathered hundreds. Between 2005 and 2009, when I conducted most of my observations, the number of people attending the debates in Club Obbligato ranged from 250 to 350. Based on the success of the first show in 2002, two ebimeeza in Luganda were created. One on Radio Simba, which was attended every Sunday by approximately 200 to 300 people, and one on CBS, the Kingdom of Buganda’s radio station, which was the largest, attended by 300 to 600 every Saturday.61 Smaller ebimeeza flourished all around town (there were ten of them in total in Kampala). All were in Luganda, and each gathered around thirty people.62 As we will see in detail in the next chapters, a few were launched up-country, especially in Masaka.

Ebimeeza were often said to have been more affordable for the “ordinary citizen” than phone-in talk shows. Yet this might not have been the case, given the increase of mobile phone ownership and the decrease in communication costs.63 Assessing how much it cost to attend was difficult, as it varied from one participant to the other. It depended on transport, and some participants actively invested in this activity by buying documentation (especially newspapers) and sometimes clothes. But basically, to attend an ekimeeza, participants first needed to get there (from the city center, it cost around USh500 at the time by collective taxi [around 0.15£], and 3,000 by boda boda [a bit less than £1]). At Club Obbligato, where having a drink was not mandatory, a soda cost USh700, whereas a beer cost between USh2,000 and USh3,000. In Mambo Bado, the ekimeeza of the kingdom’s radio station, CBS, one could not drink; people could stand freely in the audience, but those who wanted to sit on a plastic chair had to pay USh300 (0.08£). There were therefore financial differences within the audience, between people seated (around 150) and people standing (the rest). In Simbawo Akatii, the ekimeeza of Radio Simba, the system was different, as participants had to buy a drink to access the courtyard (USh700 for a soda). In all cases, attending an ekimeeza required leisure time, which attracted both people who could afford to take some and people who were idle because they were jobless.

In Kampala, many people say that the ebimeeza in Luganda were “real People’s Parliaments,” because they were supposedly more popular: “Most of our people here don’t go to Obbligato because that one is in English, not many people can speak the language. So this one [in Luganda] can attract the majority,” the presenter of one of the Luganda shows told me.64 Interestingly, however, despite their differences in reputation, the social gap between the show in English and those in Luganda was not as great as usually claimed. Variations could indeed be noticed. There were, for instance, important differences in the ethnic composition of the audiences of the shows. However, in terms of educational backgrounds in particular, the data gathered do not indicate fundamental contrasts between the ebimeeza in Luganda and the one in English. As we will see, the data indicate that the English-speaking audience did indeed gather more university graduates than the Luganda-speaking ones. But the audiences of the ebimeeza in Luganda did include an important number of educated people as well. It was precisely this gap between the reputation of the Luganda shows and their actual social composition that was of interest in my research: they were made up of populations relatively similar to those participating in the shows in English (in terms of masculinity and diploma). But they did not convey the same image.

Information about the social composition of the audience in the ebimeeza was compiled through questionnaires that were distributed in several shows. This technique was far from flawless, but it was also the most effective and reliable way available to me at the time to obtain information on the profile of the audience members at the various ebimeeza. The objective was in particular to put the data gathered through interviews and life stories in perspective. The way the questionnaires were given and completed by informants is important to take into account. It is paramount to underline that these figures should only be considered as tendencies and not definitive results.

The questionnaires were anonymous. They were distributed in three different ebimeeza in July and August of 2008. A total of 276 were filled in and analyzed. I always distributed them after obtaining authorization from the organizers and after having been introduced by them. Most of them were distributed ten minutes before the debate started. They were obviously filled out on a voluntary basis. Generally, people were happy to answer the questions and help with the research. Nevertheless, it is plausible that some did not participate because of fear of repression. Other limitations need to be taken into account, such as that the questionnaires could be completed only by people who knew how to read and write. This needs to be noted, even if, according to official statistics, the literacy rate in Kampala is up to 91 percent.65 Moreover, the questionnaires could be filled in only by people who spoke English, as, even if it would have been easy to distribute a questionnaire in Luganda, I did not have the linguistic or financial capacity at the time to analyze the answers. Despite these biases, I think it would have been a pity not to collect this information, which, in addition to being new, complemented the ethnographic observations, just as the latter helped to get around some of the limits of the survey, especially by interviewing people who could not fill in the questionnaire, and thus integrating into the interview sample people who were less educated.

Apart from providing an idea of the composition of the audience, what was at stake with the survey was to observe how much the discussions had become socially diversified since the beginning of the shows. According to this data, the first characteristic of the audience was its relative youth.

TABLE 1.1. Age of audience members at three ebimeeza

These figures need to be put into perspective, as 45 percent of Ugandans are under fourteen, and life expectancy is fifty-three years.66 It is worth noting that the average age was around thirty, whereas the founders were between forty and fifty years of age when they first started debates in Club Obbligato.

A characteristic that did not change much between the creation of the ebimeeza and the moment when the investigation was carried out was the gender of those in attendance.

TABLE 1.2. Sex of audience members at three ebimeeza

In Club Obbligato, no women completed the questionnaire. Nevertheless, there were women who attended and some who took the floor, but they never numbered more than five or six. The imbalance was also striking in the shows in Luganda, even if women were a bit better represented. Several elements explained this gap between sexes. Obviously, structural inequalities between sexes in terms of levels of education need to be taken into account.67 However, it is possible that the absence of women was linked to the fact that most ebimeeza took place in bars, which women saw as potentially damaging for their reputations; nevertheless, women were also an extremely small minority in shows that took place in gardens or courtyards. Among the six women I interviewed who regularly attended Radio One’s Ekimeeza, five took the floor each time they came, partly because the producers favored women when they registered to speak. Among them, there were two staunch political activists, one from an opposition political party and the other from the NRM. One was a former vice president of the Students’ Guild at Makerere, another three were lawyers. All these women had been to university. They had political ambitions and significant experience in public speaking in venues open to both sexes. In the shows in Luganda, the configuration was similar: the women interviewed who attended regularly were generally highly educated and actively engaged in a political party. Very often they were also part of the leadership of the show (see chapter 7).

Given the fact that the NRM has usually been praised for its achievements in integrating women into politics,68 it is worth questioning more precisely the relative absence of women. This phenomenon illustrated further the disconnection between the ebimeeza and the Local Councils, which guaranteed a place for women to engage in politics and be elected, and thus be granted access to a specific form of citizenship largely focused on the management of local issues. According to Aili Tripp, in the 1990s, women attended the lowest levels of Local Councils but were more rare in the higher ones, and women who did attend LC meetings tended to remain silent.69 They also tended to prefer women’s rather than mixed groups.70 According to Sylvia Tamale, there was generally a feeling of hostility toward women engaged in “high politics” at the end of the 1990s.71 The women speakers interviewed did indeed stress the difficulties they had in taking the floor at the ebimeeza. When they did, they were exposed to nasty remarks from the audience.72 They were very vigilant on what they wore, being careful not to show their waist or legs.73

As mentioned earlier, ethnic characteristics varied from one show to the next.74 The table below gathers ethnic group representations (as listed in the 1995 constitution) according to the regional categories usually used by Ugandans on a day-to-day basis.75

TABLE 1.3. Ethnic and regional origins of audience members at three ebimeeza

The contrast between the Ekimeeza of Radio One and the others is obvious. In the ekimeeza in English, ethnic origins were very varied. People who defined themselves as Baganda in the questionnaire were a small minority. The majority of the informants presented themselves as Northerners or Easterners, reflecting a certain distortion compared to the proportions in the Central Region and Uganda in general.76

For Club Obbligato, these results illustrate an important shift in the ethnic composition of the audience. This shift can be attributed to the fact that all the other shows were in the Luganda language and that there were no shows in a Northern or Eastern language in Kampala. Most of the Northern or Eastern members interviewed said they had not mastered Luganda enough to engage in a Luganda debate, and the Radio One Ekimeeza was the only one where they could take the floor. As such, the show became a meeting place for some Northerners and Easterners in Kampala, including politicians from Northern constituencies (see chapter 5).

The audiences were also characterized by a high level of education:

TABLE 1.4. Completion of primary school by audience members at three ebimeeza

In the three shows covered by the survey, more than half of the informants said they had completed at least primary school. The proportion was higher in Club Obbligato. I mentioned earlier that the questionnaire introduced distortions: there is a strong possibility that actually, the proportion of people who accessed formal education and completed at least primary school was in fact smaller. When more precise answers were taken into account, the proportions in the audiences were as follows:

TABLE 1.5. Diplomas held by audience members at three ebimeeza

According to UNESCO, in 2008 in Uganda, 21.65 percent of the age category concerned benefited from secondary education,77 and 3.77 percent of the age category concerned had access to university.78 Keeping in mind the distortions already mentioned, it seems safe, however, to say there is still an important gap between the ebimeeza audiences and the general population in terms of access to higher education. More than half of the informants in the English-speaking Ekimeeza had gone to university. There were approximately half that many in the shows in Luganda, however, whereas the local discourse made the ebimeeza in Luganda places where “school dropouts” could take the floor, there was a nonnegligible number of audience members who had at least finished primary school and had been to university.

Despite these high levels of education, a difference between the composition of the original group and the audience of 2008 was not deniable: in the show in English, 13.4 percent of the informants said they didn’t have a diploma, whereas the historicals were all graduates from university, successful businessmen, lawyers, and doctors. The latest statistics on the use of different languages in Uganda are very dated (1970).79 Yet what can be safely said is that speaking English remains linked with the possibility of attending school at a relatively high level. Thus, most informants who attended the debates at Club Obbligato were relatively well educated (most had been to secondary school). Nevertheless, some nuances must be taken into account, especially differences between spectators and orators: these will be investigated closely in chapter 9. Some members at Club Obbligato understood English but did not feel fluent enough to take the floor. In the ebimeeza in Luganda, it was possible that people who took the floor were very educated, even if generally the people who attended were less educated. The bottom line was that one could find members of the English-speaking Ekimeeza who had only some very basic education, whereas other participants in Luganda-language shows could be graduates from university.

The questionnaires showed that there was a certain variety in terms of professions and important changes compared to the profile of the historicals in that regard. The original nucleus of wealthy businessmen was open to a more varied population of students and teachers, but also employees, security personnel, social workers, and so forth. It is also worth mentioning that the number of members whose parents both were farmers was very high in the case of the English-speaking Ekimeeza compared to the others (54.4 percent versus 33.6 percent for Mambo Bado on CBS and 19 percent for Simba): again, this goes against the widespread idea that the show in English was more “urban” than the ones in Luganda, or that “rural folks” preferred to frequent the shows in Luganda.

The enlargement of the population and the relative disconnection of the ebimeeza from the original sociability practices that led to their emergence was illustrated by the fact that some members interviewed stated that they would not have frequented Club Obbligato if it had not been for the show, because of the price of the drinks, the presence of alcohol, or because they did not feel it was their place to be. These specific members, who came from more modest backgrounds, had different sociability practices and political heritages. The mere contrast between the locations where the interviews with different members of the ebimeeza took place was per se amazing and illustrated this social diversity. In the same day, interview locations ranged from the huge and luxurious offices of a business lawyer to an insalubrious small cabin in the slums of Naguru or Nakulabye.

Despite the fact that they were presented as “People’s Parliaments,” the ebimeeza were not the reflection of the integration and diffusion of ideals of radical democracy. They were the offspring of practices of sociability and the representations of legitimate political action that were typical of the educated wealthy male circles of Kampala. After the discussions started being broadcast, the composition of the audience was enlarged: new generations of speakers appeared, especially students, party mobilizers, and Northerners, in the case of Club Obbligato. Although the Ekimeeza was still dominated by educated members of the Ugandan population, it did accommodate a wider spectrum of social and economic statuses. By reconstituting the early history of these discussions, however, we can get a better view of the ways in which the Ganda business class and the intellectual guerrillas of the West of Uganda became mutually interconnected after the violent military takeover in 1986, and together participated in the reinvention of an elitist sociability. As such, the ebimeeza can be seen as one of the sites where a “reciprocal assimilation of elites” occurred, to use Jean-François Bayart’s words.80 That is to say, a site where historically distinct components of the elite could together reinvent a political culture, reinvent the parameters of class domination, and, through their social and economic alliance, rebuild a sociopolitical order. It illustrates how the wealthy, liberal, and moderate Ganda elite class was able to socially materialize its alliance with the leftist military elite of the West, through a heterodox interpretation of the Movement revolution. Last, this elitist and intellectual heritage of the ebimeeza needs to be taken into account in order to understand how the new generation of speakers understood themselves and their part in the polity when they took the floor. As we will see in detail below, far from discarding this distinguished heritage, they embraced it.