Читать книгу Talkative Polity - Florence Brisset-Foucault - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHREE

The Ebimeeza and the Partisanization of Ugandan Politics

IN UGANDA, THE PARTISANIZATION OF POLITICAL LIFE, UNDERSTOOD as the “process of ascendency of political parties in political competition,” has fostered debates that have a much longer history than the NRM takeover.1 The way political competition should be organized has been a central issue of controversy among politicians, and the citizenry alike, since the late 1950s.2 As mentioned earlier, the historicals of Club Obbligato were very hostile to the influence of political parties on the debates, reflecting an intellectual reluctance grounded in their upper-class belonging. However, parties were very visible in the ebimeeza. In the shows, these contradictory dynamics had implications regarding the way the rules of the deliberations were to be defined. The way political “balance” or “pluralism” was understood, the very concrete ways in which people were seated, how they were addressed, and how they introduced themselves at the microphone (according to party tickets or not) were all constant topics of discussion among ebimeeza orators and organizers.

The ebimeeza were the product of the immediate political context of the year 2000, and of the particular pattern of electoral competition in force in Uganda at the time. Their emergence and success were directly linked to the micropolitics of political parties and their social grounding. The ebimeeza cannot be understood in isolation from this, and, in return, they provide a rich empirical opportunity to study the embedment of parties within society, against the background of a literature that has often considered African parties as empty shells, and that has largely focused on party elites.3 The organization of national and local political competition as a race between political parties is neither obvious nor straightforward. It is the result of varied local and international dynamics. Both the partisanization of political life and the institutionalization of parties as organizations rely on initiatives from above and on evolutions from below. An existing landscape of political organizations and sociabilities nourishes these processes.

The ebimeeza provide an empirical opportunity to observe closely the transformations of the patterns of political competition at the very moment when multipartyism was reintroduced in Uganda.4 Their close study illustrates what Ugandans made, in very pragmatic ways, of party labels and how they routinely imagined political competition in such a context. It shows how the partisanization of political life in Uganda was fed in contradictory ways by alternative conceptions of political competition, and particular practices of mobilization and patronage, but also the routine functioning of the media. The ebimeeza show in particular how partisanization has built on the initiatives, from below, of marginalized activists within each party.5

The Media and the Imagination of Political Competition in a No-Party Democracy

When the ebimeeza began, Ugandans were still living within a no-party system. One of the most important principles according to which the shows were organized was the idea that they should be “balanced.” However, there were uncertainties as to how this balance was to be defined: Was it going to be based on individual positions rather than easily recognizable political entities such as parties? In a way, these highly concrete dilemmas involved the very ideas and principles that were at stake when the NRM imagined and installed its model of democracy. Study of the ebimeeza thus allows us to analyze the way the Movement model was integrated, deliberated, and criticized by citizens and the media.

If one were to respect literally the no-party democracy doxa, then everybody belonged to the Movement, and the idea of party solidarity or political discipline did not make sense; individual opinions prevailed. In Parliament, for instance, before 2005, MPs could sit wherever they wanted.6 Generally speaking, however, there has been a wide gap between the theory and the practice of Movementism since 1986: old party identifications were still influential under the “no-party” arrangement. At the end of the 1990s, Nelson Kasfir noted that the NRM “permitted a de facto, though unacknowledged, form of party competition to become the basis for the actual practice of Ugandan electoral democracy.”7

Beyond party labels, relatively stable political antagonisms and solidarities surfaced. The constitutional process (1988–1995) in particular saw the polarization of the national debate and of the political class between “multipartyists” and “Movementists.”8 This antagonism was not self-evident at first, because in the official ideology, multipartyism was to follow Movementism.9 However, it was soon simplified into a polarization between “government” on the one hand, and “opposition” on the other.10

Paradoxically, in the years that followed, the NRM leadership was the strongest to challenge the Movementist definition of political competition and encourage the formation of easily identifiable political groupings that were retaking party lines, especially through the creation of the Movement caucus.11 The core of the NRM, around the president, knew how to identify the “true” NRM members from the rest (i.e., persons most loyal to the government and the president).12 Through political and financial support granted to electoral candidates who were deemed more loyal than others, the executive rapidly encouraged allegiance and discipline.

What used to differentiate the NRM fundamentally from a political party was the fact that all citizens were part of it, and that consequently, internal pluralism was accommodated. This was challenged when politicians critical of the presidential line were “expelled,” and when the Movement endorsed Yoweri Museveni as their official candidate for the 2001 election.13 On October 30, 2000, Kizza Besigye, a former personal doctor of the president but more importantly a former freedom fighter and cabinet minister, declared himself a candidate for the presidential election against Museveni. This highly contested electoral campaign divided the NRM, and the “opposition” camp was strengthened.

All this does not mean that the Movement ideology was a smoke screen. It was taken seriously, even by people who are today Museveni’s staunchest opponents, and constantly discussed by Ugandans from all walks of life. The political ideas and principles at stake resonated with older political and moral ideals and impacted the way many Ugandans, from all political sides, imagine the good polity. However, the binary opposition between two identifiable political groupings, “government” and “opposition,” which challenged the Movement model of political confrontation, quickly became structural. It was along these lines that the media staged a national debate and defined political “balance.”

Even if candidates did not run for elections under a party ticket, they were presented in the media according to their party affiliations, or according to their acknowledged membership of the “opposition” or the “government” group. In Uganda as elsewhere, most journalists assimilate “neutrality” with “balance,” and “objectivity” with a “juxtaposition of opposed points of view.”14 According to the first producer of Radio One’s Ekimeeza, establishing that the show was “balanced” meant gaining credibility and avoiding becoming a target for repression: “There is some relative freedom in relation with the media. Just relative. Because you will hear on the talk shows people will come in and say all sort of things, but if you notice, the politically accepted talk shows are those that are balanced.”15 Not being balanced provided grounds for state repression, which could be acknowledged by some as legitimate by media producers, as one said about an occasion when one of his shows attracted the authorities’ hostility: “The presenter had to give the other side of [the story]. . . . So that there’s a balance. But he didn’t, which was very wrong.”16 Respecting what is imagined as political balance reflects a specific professional culture and the anticipation of repression, both of which may coincide, once more.

“Balance” also results from the legal provisions concerning equal coverage, and especially the 2000 Presidential Act, even if it officially applies only to public media. Concretely, this ideal of balance is usually translated by the fact that when talk shows take place in-studio, producers invite two people: one representing government and the other the opposition.17 This binary polarization is also encouraged by the fact that journalists marginalize candidates from small parties, and because they think that creating a straightforward confrontation on the air is more appealing.18 This professional culture thus goes against the official Movement democracy credo, although not necessarily intentionally, and ends up encouraging alternative representations of political pluralism.

The Pragmatics and Ideologies of Political Competition in the Ebimeeza

The ebimeeza were quite different from indoor talk shows, and the ways in which political competition was to be organized were never self-evident. As we will see in detail, they were strongly influenced by the culture of the school debate clubs. School debates follow the Westminster model of politics: they are fundamentally confrontational, and usually feature a “proposition” side against an “opposition” side, with both sides represented by an equal number of orators.19 Pointing out the links between the ebimeeza and the Westminster model of debate helps in understanding their agonistic, binary, and competitive character. But it also helps explain why they were ambivalent toward party politics, as parties are usually officially forbidden from debating societies, even if such societies are full of intrigue and alliances.20

For some journalists, producing an ekimeeza was more politically loaded than just applying the routine rules of the profession or reproducing habits acquired at school. It was an opportunity to stage a pluralist debate, which was seen as an opportunity at least to experiment with the ideal of multiparty politics. As one journalist told me: “The ekimeeza is like to create an ideal. It’s just like having a pilot project. When you say, ‘What would happen if the political space in Uganda was opened?’ [. . .] Perhaps it was the starting point of the ekimeeza, to reflect what a parliament should be. A proper parliament. You know where different views are respected.”21

However, this was more an exception than a rule, and for most of the organizers, the adoption of the categories “government” versus “opposition” corresponded only to the reapplication of journalistic practices or to the Westminster ethos of political balance. It was not presented as an act of resistance against the Movement system.

As mentioned earlier, the first discussions in Club Obbligato started in the context of the announcement of Besigye’s candidacy for the presidential election in 2000. This divided the Ekimeeza’s historicals as it did the NRM. “We had people [. . .] who were supporting Kizza Besigye; we had big people who were supporting President Museveni,” Chairman Wasula explained.22 This had an influence on the way the debates were to be organized.

Ebimeeza members used a whole range of different words to designate the way the political architecture was being redesigned: they talked of different “sides, wings, camps, tendencies, political attachments, ideologies, affiliations, political backgrounds, parties,” and the like.23 They imagined different lines of division: “pro- and antiestablishment,” “multipartyists against Movementists,” or “opposition against government.” People were not unanimous on how to organize the debate. As one orator explained: “Of course the chairman of the ekimeeza could always want to balance the debate, so if he has called two people speaking in favor of government, then he would make sure he would call other people, two people speaking against, from opposition to come and you know, so as it appears as a debate.”24 But the chairman himself, in accordance with the views set out in chapter 1, was rather hostile to this option:

That is a new phenomenon. We practice it now, but I want to discourage it personally. Because it will polarize the discussion. People will start identifying themselves as “yes I am this, I am that.” . . . I discourage it personally. I don’t want people to tell us where they belong. I just want their views, that’s it. [. . .] They were saying “opposition,” “movement.” I said no: “pro the topic,” “against the topic.”25

Despite the chairman’s and many historicals’ hostility, the Ekimeeza quickly adopted this binary system in its routine functioning. As a journalist explained in 2002: “These public talk shows have become Movement versus multiparty discussion forums. This explains why the more vocal Movement and multiparty faces hop from one show to the next, if only to bat for their side. [. . .] The political opposition (multipartyists) is particularly loud at these gatherings.”26 Interestingly, some members encouraged the adoption of this binary system because they were attached to the no-party system: they preferred orators to engage in oratorical matches according to fluid lines such as “opposition” and “proposition,” instead of competing based on their party belongings. However, this containment of political party identifications worked only to a certain extent.

The lists of orators established by the organizers of the ebimeeza were an interesting aid for examining these dynamics of political polarization and partisanization. In Club Obbligato, the lists illustrated that the polarization “proposition” versus “opposition,” which was supposed to be fluid and change according to the topic of debate, was quickly reinterpreted, both by members and by organizers, as “government” versus “opposition.” As the chairman explained:

In the beginning, we were having one single [. . .] list, one [person] following the other as [they] registered. We realized we could have ten people in a row from one side, one divide of the political sphere, and that was unfair. One speaker after the other, they were all saying the same thing. So . . . Hmm, we said no, [we] should separate. [. . .] So we have one speaker from the ruling party, one from the opposition. Ruling party, opposition—we try to balance it.27

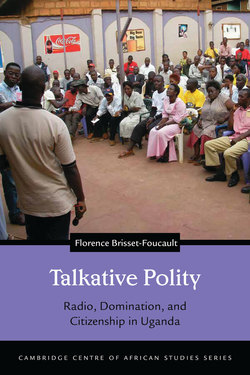

FIGURE 3.1. Club Obbligato’s coordinator establishes two lists of orators, 2007. (Photo by author.)

In order to do this, potential orators wrote their names on a piece of paper. Then a person called the coordinator (see chapter 7) had to make a list, usually divided into two columns, according to political leanings. He then gave the list to the chairman, for his use in calling the speakers to the microphone.28

There were various coordinators in Club Obbligato, and they had different ways of separating the orators, which revealed disagreements in how the competition should be organized and varied ideas of what a “balanced debate” meant.29 The first pattern, which was the most frequent in the archives I found, was “proposition” versus “opposition.” A second pattern opposed a “side A” against a “side B.” A third opposed a column titled “NRM” against a column titled “opposition.”

Even when topics or patterns changed, I found that some orators were in the same columns most of the time, which suggests that coordinators tended to gather people they identified as belonging to one side or the other because they knew them and their usual beliefs or leanings.30

Generally speaking, it was difficult for orators to escape being categorized by other members or organizers as belonging to one side or the other. It was part of the fun of the show for spectators to guess orators’ loyalties. Also, as the chairman said: “Now we know who belongs to where. We know who belongs to opposition, and we know who belongs to the ruling party. So we separate them that way.”31 An orator explained: “At that time, everybody could stand and talk on a topical issue as an individual. But it was through the words or the way he brings about his point that you can realize how the other is against government, or the other is progovernment.”32

Some members enthusiastically embraced these constraints of identification, partly because the ebimeeza are spheres of political recruitment, which encourages demonstrating one’s loyalty toward a political organization (see discussion later in this chapter). As an orator explained:

Usually we have two parties in the bimeeza. The opposition and the government people. [. . .] Let’s say a member of the opposition, whenever the debate is concerning the government, you are supposed to look for negative aspects only (he laughs). When you look for the positive aspects, you maybe give morale to the government that they are doing very good, so it’s not what you’re supposed to do. You look for the negative aspect. If you are not a good person to make a negative analysis, next time they don’t call you, saying that person misrepresented us.33

At Simbawo Akatii, Radio Simba’s ekimeeza, things were different than at Club Obbligato. Even if the binary structure was strong, the debate gave more importance to party identities. Producers agreed to use party labels and encouraged orators to identify themselves with a partisan repertoire because they wanted to make sure the debate was “balanced.” When people registered, they indicated their party membership or preference to the organizers. Afterward, the host of the debate, Dick Nvule, called them in a certain order so as to respect a binary balance between “government” and “opposition.” He explained during an interview how government itself encouraged a certain partisanization of the debate, as the adoption of party labels in the show was thought of as a way to avoid repression. Paradoxically, before the return to multipartyism in 2005, organizing a political debate that reproduced a multiparty system was the result less of challenging the official ideology of a no-party democracy than of an adaptation to the authorities’ injunctions:

The reason why we did that, asking people [. . .] to expose the political parties they come from, that was something that we . . . Government was always saying that we radio moderators of political talk shows, we normally prefer having people from the opposition to speak and we were saying no. But the government was insisting. So we said “okay,” now whenever we call them, we shall say “Okay, this [one] is from the ruling party; this [one] is from the opposition; and this is an independent,” so that the audience can choose who is telling lies between the moderators and the government.

Q: So that’s a way of showing the government that the show is balanced?

A: Yes!

Q: Yes?

A: Yes! Because government was attacking us that we normally take on the opposition guys so that’s why we decided okay, we should always expose which political party they come from. To show them that the show is balanced! So if you [NRM] don’t have good speakers, you are the ones to blame, not us! You should mobilize your guys and you have good speakers.34

The competitive and polarized nature of debates also came from what orators thought were the expectations of the moderator in terms of the quality of the show. As an orator explained:

The chairman is not interested in his program not working very well. He wants the sharp people who can counter each other. But when they call you and you say “wawawawaw,” and you look to be weak . . . They can tell you we don’t want that guy, we want some good people with good reasoning. [. . .] There are people who come there and they don’t debate. They put their name on a paper, but they can spend months without debating.35

However, when observing the spatial organization of the debates at Club Obbligato or at Radio Simba, the division into two sides or according to political party lines does not stand out. That was not encouraged by the organizers. People could sit wherever they wished, and, as we will see later, at Club Obbligato and at Radio Simba, seating strategies reflected mainly the status orators claimed or thought they had within the assembly rather than any political solidarity or antagonism. On the contrary, one striking thing in all the ebimeeza was how much people from different political “sides” or “parties” were sitting, chatting, and laughing together, sharing drinks and food in an informal atmosphere.

An Opportunity for Opposition Political Parties

Despite the historicals’ hostility, the ebimeeza were strongly and very early on intertwined with party politics. Before the 2005 reform, they were a convenient venue for opposition parties (but also the NRM, as we will see below) to try to overcome the fact that they could not organize political rallies or present candidates in the elections. There they could meet citizens and ensure the continuity of their ideas and their structures.36 But the ebimeeza were also linked to intraparty struggles and were used by subaltern activists to gain prominence within their own parties.

Before 2005, parties existed but could not register members or hold rallies. Opportunities to meet citizens officially were thus relatively scarce: they happened on a microscale (typically within a political leader’s circle of sociability or clientele networks). Collective mobilization events had to be organized by politicians on an individual basis. They were often frowned upon by the authorities and restricted to electoral campaign periods. As Giovanni Carbone has shown convincingly, political parties’ leaderships, especially in the Democratic Party, developed tactics to use any opportunities of interaction with supporters and citizens in order to ensure their organization’s continuity both in people’s minds and in organizational terms. The DP was notably keen on organizing seminars and conferences, and so using “organizational repertoires,”37 which were similar to the ebimeeza (i.e., based on intellectual debate and interactions rather than mass rallies).38 But the ebimeeza were used by all parties. As a Forum for Democratic Change member of Parliament from Northern Uganda told me: “There was a time [when] a public rally was dispersed for members of the opposition. And this [ekimeeza] is the venue where you come and start addressing issues. You need a meeting place!”39 The shows were also opportunities to ensure a certain visibility of the organization: beyond the speeches themselves, some participants displayed their party colors (yellow for the NRM; green for DP; red for UPC [Uganda People’s Congress]; orange and later blue for FDC), by carefully picking their outfits. Last, the ebimeeza were of course a free media space in an increasingly commercialized context. As we will see in detail, the partisanization was also strengthened through individual ambitions and agendas of social advancement. Some participants hoped to catch the eye of a potential mentor, or to be recruited as a political campaigner by demonstrating their loyalty to a party.

The strategy adopted by opposition politicians toward the ebimeeza followed two different patterns. First, on an individual basis, important members of the opposition leadership began to frequent Club Obbligato informally, as early as 2001 (on these individualized approaches, see chapter 5). However, the presence of the opposition in these new spheres of discussion also took place in a more coordinated way in the context of the 2000–2001 election campaign, as one orator explained:

Q: What led you to attend these debates?