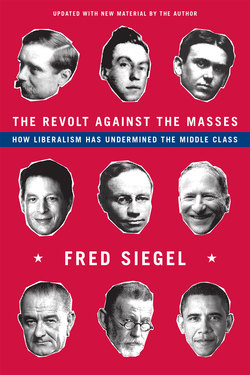

Читать книгу The Revolt Against the Masses - Fred Siegel - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

“Randolph Bourne Writing Novels” About Main Street

In the 1920s, D.H. Lawrence was following a well-trodden path in England and Europe when he wrote one of his most anthologized poems, “How Beastly the Bourgeois Is.” In it, Lawrence compares the middle class, “especially the male of the species,” to “a fungus, living on the remains of a bygone life/sucking his life out of the dead leaves of greater life than his own.” In the nineteenth century, English aesthetes such as John Ruskin and Oscar Wilde, German thinkers such as Adam Muller and Ferdinand Tönnies, who mourned the lost glory of the medieval world, and French litterateurs, most notably Charles Baudelaire and Gustave Flaubert, had made careers of flaying the bourgeoisie. Lawrence joined this European tradition in his hatred for the middle class as the bearer of reason, democracy, and capitalism. In the words of the great French historian of Communism François Furet, the middle class was “petty, ugly, miserly, laborious, stick-in-the-muds, while artists were great, beautiful, brilliant, and bohemian.” Flaubert, for his part, argued that politically, “the only rational thing . . . is a government of Mandarins,” and that “the whole dream of democracy is to raise the proletarian to the level of stupidity attained by the bourgeois.”

But it was only in the 1920s that this contempt for the bourgeoisie—and with it a hostility to America as the quintessentially middle-class, democratic, and capitalist nation—was brought to a wide readership on these shores by a new generation of writers, including Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and H.L. Mencken. Critiques of popular culture were nothing new in twentieth-century America. Americans pioneered popular culture because big-city entertainments had to appeal to uprooted people who came from a bewildering diversity of cultures ranging from rural America to the peasant backwaters of eastern and southern Europe. In the World War I era, the rise of illustrated newspapers, radio, and movies—media that appealed to the immigrant masses, assumed to be of a low IQ—produced a hard rain of criticism. Genteel traditionalists charged that popular recreations not only pandered to the most brutish instincts of America’s “primitive blockheads” and urban peasants, but also threatened to swamp high culture in a wave of brackish effusions. The Progressives of the early twentieth century blamed the corrupt capitalists for turning popular entertainment into a moral swamp in which business interests submerged the worthy folk cultures of earlier eras.

But while the Progressives had hoped to redeem America’s virtue, the mass-culture critics of the 1920s hoped to remake America in the image of Europe. The leading literary critic Van Wyck Brooks, who idealized Europe, decried the growing separation between highbrow and lowbrow cultures. A self-styled Socialist, Brooks yearned for an “organic” society and scorned the common man as a “simple moron” who needed the leadership of artists and writers.

For liberals, the great revelation of 1919 that they carried into the 1920s was that middle-class society at large, and not just the Bible Belters with their restrictive mores, was to blame for their subjugation. Their disdain for Main Street was matched by their contempt for the detritus of urban popular culture. Referring to most Americans as “the herd,” they saw the industrialism that raised standards of living as a pernicious “degradation” imposed by a country organized around the needs of the middle class. The new popular culture of Broadway shows, movies, baseball, and Coney Island were all “makeshifts of despair,” part of the proof that America was a “joyless” land. Brooks compared the United States to a “primeval monster” that was “relentlessly concentrated in the appetite of the moment” and that knew “nothing of its own vast, inert nerveless body, encrusted with parasites and half-indistinguishable from the slime in which it moves.”

In the 1920s, the first decade in which women could vote, what looked like freedom and progress to most white Americans was an affront to liberal intellectuals, who were cultivating their own alienation. Increasingly conscious of themselves as a group, liberal writers and intellectuals, though more widely read than at any time in the past, experienced the Twenties as a time when their art was stymied by American philistinism. The public mood of the decade was upbeat, buoyed by prosperity and also by the dramatic arrival of electricity, the automobile, and the radio, which brought classical and commercial music to the masses. To the intellectual coterie, this mood was a Calvary. The creative class was being crucified, asserted Mencken, by the inferior breeds of humanity who had presumptuously betrayed their proper role as peasants by crossing the Atlantic from Europe and breeding each other into New World idiocy.

“These writers,” wrote their chronicler Malcolm Cowley, “were united into one crusading army by their revolt” against the American tradition as they understood it. “In the exciting years 1919–1920,” wrote Cowley, “they seized power in the literary world . . . almost like the Bolsheviks in Russia.” Edmund Wilson concurred; he took pride in the belief that his generation of critics and writers had launched an unprecedented and continuous attack on their own culture. Edmund Wilson’s bitterness over President Wilson and World War I corroded like acid on the skin. Speaking of the war, which he had experienced firsthand as a medical-corps stretcher bearer, Wilson hissed: “I should be insincere to make it appear that the deaths of this ‘poor white trash’ of the South and the rest made me feel half so bitter as the mere conscription or enlistment of any of my friends.”

The cultural qualities associated with political liberalism were best expressed in the writings of Minnesota-born and Yale-educated Sinclair Lewis. “Shaped by the Herbert Croly age in American thinking,” Lewis was “Randolph Bourne writing novels,” explained the historian, novelist, and literary critic Bernard DeVoto. Lewis’s novels of his native Midwest were “stocked . . . with unforgettable symbols of business domination,” noted historian Arthur Schlesinger wrote. “They fixed the image of America, not just for the intellectuals of his own generation, but for the world in the next half century.”

Main Street was Sinclair Lewis’s first bestseller. A sardonic sally at the small-town American middle class and its commercial culture, the book was published just before “the back-slapping, glad-handing” Warren G. Harding brought his cronies and their card games (but not his mistress) into the White House. Contemporaries saw Main Street as more than a novel: It was the true account of American life. The novel’s impact was compared to that of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The literary historian and Lewis biographer Mark Schorer described it as the “most sensational event in twentieth-century American publishing history.” More than any other book, Main Street gave the political label “liberal” its cultural content.

Lewis presented himself as a man of the prairies who knew America intimately. But Schorer noted that he knew little of the United States and almost nothing of its history. Rather, he was a literary man through and through—though some would describe him as an academic manqué because he made up for his lack of experience by doing detailed research—and he drew on the fiction of H.G. Wells (after whom he had named a son) for the themes of his early writings. His worldview came from reading the arguments of the German Darwinist Ernest Haeckel on evolution, the Hungarian theorist of social degeneration Max Nordau, and the Belgian symbolist playwright Comte Maeterlinck, who won the Nobel Prize in 1911. He was not very interested in politics per se, but, while still at Yale, the twenty-one-year-old Lewis was drawn to Upton Sinclair’s utopian Community Helicon Hall, in then bucolic Englewood, New Jersey. In its brief history, Helicon Hall—purchased with the money Upton Sinclair made from The Jungle—drew in such luminaries as William James, Lincoln Steffens, and Emma Goldman. A few years later, in 1909, Lewis lived for a time in another would-be utopia, Jack London’s Carmel commune. While there, he sold story plots to London, whose imagination had begun to run dry. From 1909 to his triumph with Main Street in 1920, Lewis was immersed in the literary world.

Main Street caught the post-war literary mood of disillusion perfectly. It distilled and amplified the sentiments of Americans who thought of themselves as members of a creative class stifled by the conventions of provincial life. It’s the story of Carol Kennicott, a sensitive young woman from the big city who is trapped by a nearly loveless marriage with a stodgy middle-class husband. She’s also imprisoned by small-town life in Gopher Prairie, a dreary midwestern settlement dominated by Rotarians. Carol, like Randolph Bourne, was repelled by the “grayness” and “dullness” of “shabby” town life in America. Unlike the towns of an idealized Europe, characterized by “noble aspiration” and a “fine aristocratic pride,” Gopher Prairie (modeled on Lewis’s Minnesota hometown of Sauk Centre) was defined by the “men of the cash-register…who make the town a sterile oligarchy.”

Carol is tormented by the self-satisfied mediocrity that surrounds her. She dreams of a “better life,” of “a more conscious life,” though she is never able to define it. In his notes for Main Street, Lewis wrote of Carol Kennicott: “Her desire for beauty in prairie towns was but one tiny aspect of a world-wide demand [for] alteration of all our modes of being and doing business.”

Carol and the people she’s drawn to, such as Guy Pollock, a lawyer twenty years her senior, provided a stock of tropes for the next half century’s commentaries about the conformity of American life. “I had decided to leave here,” Guy tells Carol. “Then I found that the Village Virus had me. . . That’s all of the biography of a living dead man.” “The Village Virus,” as Carol explains it to herself, is contentment: “The contentment of the quiet dead, who are scornful of the living for their restless walking. It is negation canonized as the one positive virtue. It is the prohibition of happiness. It is slavery self-sought and self-defended. It is dullness made God.” Americans, Carol says, are “a savorless people, gulping tasteless food, and sitting afterward, coatless and thoughtless, in rocking-chairs prickly with inane decorations, listening to mechanical music, saying mechanical things about the excellence of Ford automobiles, and viewing themselves as the greatest race in the world.”