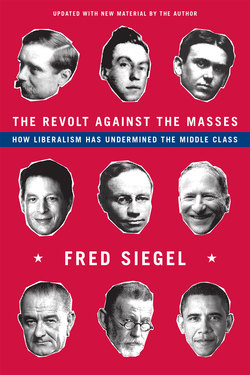

Читать книгу The Revolt Against the Masses - Fred Siegel - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

This short book is not a comprehensive history of American liberalism. A number of important figures and episodes are merely glossed over. Instead, it rewrites the history of modern American liberalism. It shows that what we think of liberalism today—the top-and-bottom coalition we associate with President Obama—began not with Progressivism or the New Deal but rather in the wake of the post–World War I disillusionment with American society. In the Twenties, the first writers and thinkers to call themselves liberals adopted the hostility to bourgeois life that had long characterized European intellectuals of both the left and the right. The aim of liberalism’s founding writers and thinkers—such as Herbert Croly, Randolph Bourne, H.G. Wells, Sinclair Lewis, and H.L. Mencken—was to create an American aristocracy of sorts, to provide the same sense of hierarchy and order long associated with European statism.

Like communism, Fabianism, and fascism, modern liberalism was a vanguard movement born of a new class of politically self-conscious intellectuals. Critical of mass democracy and middle-class capitalism, liberals despised the individual businessman’s pursuit of profit as well as the conventional individual’s self-interested pursuit of success, both of which were made possible by the lineaments of the limited nineteenth-century state.

Snobbery is not new to liberalism. But the actual history of liberalism will be new to most readers, which is my reason for writing this book. The history of liberalism as written by liberal historians begins either with the pre-WWI Progressive movement or, more likely, with the New Deal of the 1930s. In the plumb-line account usually wholesaled, there is a direct ascent from the Progressives to the social salvation represented by the New Deal to the Great Society and on up to the present. The Progressives, it’s said, were the first to show that big non-constitutional government could be used to solve big problems. After the yahoos of the 1920s put the country to sleep for a decade, leading to the stock-market crash, the New Deal rode to the rescue to establish the beau ideal for future governance. Conservatives tell a similar story, but theirs is an account of descent, from liberty into “statism.”

But the story isn’t quite true at beginning, middle, or end. The story of liberalism is more than an account of how the administrative state broke free of its constitutional bonds. Liberalism, like its rivals, including communism, fascism, and social democracy, emerged as part of the early twentieth century’s intellectual response to the newly emergent realities of mass production, mass politics, and mass culture. Like fascism and communism, liberalism was strongly influenced by the Nietzschean ideal of a true aristocracy that might serve as a corrective to the perceived debasements of modern commercial society shorn of traditional hierarchies. It was liberals’ claim to be an aristocracy based on talent and sensibility that helped define the 1960s and ’70s. It was then that highly educated liberals—acting, they said, on behalf of African Americans—pushed aside the social-democratic trade unionists within the Democratic Party.

Liberalism was far more intellectually permeable, and far more politically adaptable, than most of its competitors and more willing than all but the trade-union-tied social democrats to work through the existing government structures. These qualities brought it to the forefront of American life. But it nonetheless represents a distinct ethos, a stylized set of political postures often at odds with America’s democratic, capitalist, and egalitarian traditions.

The set of cultural and emotional attachments, the political libido of liberalism, so to speak, coalesced in the wake of WWI in an angry repudiation of Progressivism and Woodrow Wilson. Modern liberalism preceded the New Deal by more than a decade. The very term “liberal,” in its modern usage, was coined by writers and intellectuals who defined themselves by their hostility to the middle class and the moralistic Progressives who had imposed Prohibition in 1919. As The Revolt Against the Masses will show, liberalism began as a fervent reaction to wartime Wilsonian Progressivism, and it took its still current cultural shape in the 1920s well before the Great Depression came crashing down on the country. It was in the seminal 1920s that the strong strain of snobbery, so pervasive among today’s gentry liberals, first defined the then nascent ideology of liberalism.

The best short credo of liberalism came from the pen of the once canonical left-wing literary historian Vernon Parrington in the late 1920s. “Rid society of the dictatorship of the middle class,” Parrington insisted, referring to both democracy and capitalism, “and the artist and the scientist will erect in America a civilization that may become, what civilization was in earlier days, a thing to be respected.” Alienated from middle-class American life, liberalism drew on an idealized image of “organic” pre-modern folkways and rhapsodized about a future harmony that would reestablish the proper hierarchy of virtue in a post-bourgeois, post-democratic world. In the mid-1950s during a brief reconciliation between liberals and their country, the literary critic Lionel Trilling noted that “for the first time in the history of the modern American intellectual, America is not to be conceived of as a priori the vulgarest and stupidest nation of the world.” This novelty soon passed.

The ideals of the 1920s liberals were, by way of the statist and technocratic elements of the 1930s, carried forward into the 1960s. It was in the 1960s that liberals, even more than conservatives, laid siege to the social-solidarity heritage of the New Deal. In the name of good causes such as opposition to racism and the war in Vietnam, post–New Deal upper-middle-class liberals looked to remake America in their own image by enhancing their own power. They defined middle-class Americans, including those who made it into modest prosperity through unionized work, as the unenlightened objects of their enmity. Much of the middle and lower-middle class, subject to liberal experiments in schooling, crime, and gender relations, reciprocated the animosity. Liberal social programs to combat poverty and reform the schools, their failures now long institutionalized, have produced a government whose grasp far exceeds its competence and whose costs are carried by the private-sector middle class. Like corrupt Harlem congressman Charley Rangel, who did his best to keep new businesses out of Harlem so that he could fend off rivals and accumulate anti-poverty money for his political friends and allies, liberalism has been dedicated to preserving the problems for which it presents itself as the solution.

In today’s America, those who claim to be morally superior all too often enjoy both neo–Gilded Age wealth and close ties to government. After the government-driven failures and excesses of the past forty years, liberalism has become an ugly blend of sanctimony, self-interest, and social connections. When the editor-in-chief of the popular liberal website Slate, frustrated with opposition to Obama’s expansion of the federal government, entitled an article “Down with the People,” he echoed the assumption that has driven liberalism since its inception.

Liberalism, as a search for status, is sufficiently adaptable that even in failure, self-satisfaction trumps self-examination. As the critic Edmund Wilson noted without irony, the liberal (or “progressive reformer,” in his term) has “evolved a psychological mechanism which enables him to turn moral judgments against himself into moral judgments against society.”

This is a book about the inner life of American liberalism over the past ninety years and its love affair with its own ambitions and emotional impulses. Liberals believe that they deserve more power because they act on behalf of people’s best interests—even if the darn fools don’t know it.