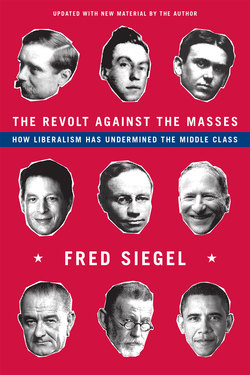

Читать книгу The Revolt Against the Masses - Fred Siegel - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPreface to the Paperback Edition

In that sense, Marcuse shared with the victims of Sinclair Lewis the fallacy that the middle class was in control, that it did in fact shape its own political and moral ends.

—RONALD BERMAN, 1975

Barack Obama’s first term in office was the culmination of the hopes that the original liberals of the early 1920s, writers and intellectuals enthralled by Sinclair Lewis’s Main Street, placed in a political transformation that could marginalize the middle class. “The ’20s,” explained literary critic Granville Hicks, “asked what a man was against, not what he was for.” That was the spirit that preceded and prepared the way for Barack Obama’s rise to power.

In 2008, the many failings of George W. Bush’s big-government Republicanism—accompanied by the adoration of Obama, by a press best described as political operatives with bylines—obscured the substantial changes that accompanied the new president into office. When Obama spoke of his “transformative” presidency, he was announcing that for the first time a new top-and-bottom coalition was taking power. By the 1960s, the middle class had ceased to be able to “shape its own political and moral ends.” But while the middle class had been weakened, its influence was still consequential, and for a time President Clinton drew the middle class back into the fold of an increasingly liberal Democratic Party.

Obama, however, reversed Clinton’s course. Obama represented the liberal faith that holds that no matter what the malady, and despite the evidence, a more powerful, more costly central government, paid for by middle-income taxpayers, is the cure. The Revolt Against the Masses describes how the seeds of Obama’s failings were planted in the years immediately after World War I when contemporary liberalism first took root.