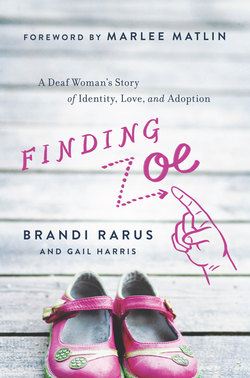

Читать книгу Finding Zoe - Gail Harris - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter One

SUDDENLY SOUNDLESS

THE BLINDING LIGHT is what I remember most. I wanted to put my hands over my eyes but was too weak to do so. It was 2:00 AM, and I was lying face up in the emergency room, more scared than I can say. I don’t remember much else before being electrocuted, or so it felt, but I do remember the doctor turning me over, pushing aside my hospital gown, and rubbing my lower back with alcohol. I can smell it now.

Then came the blow—a sharp prick sending excruciating shock waves up to my head and down to my toes. I let out a scream, which my mother, who was outside in the hallway, couldn’t bear to hear. I was only six years old. The doctor had given me a spinal tap, and there was nothing left for my mother to do except swallow her tears and wait for the results.

Thus began two weeks of hell for her and two weeks of drifting in and out of sleep—rather peacefully—for me. The days leading up to that night, when I was burning up with a fever, had been much worse for me. I remember reaching into the freezer for ice cubes to put on my forehead. It was March 1974; I was in kindergarten. We lived in Naperville, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago. My mother had already taken me to the doctor, who said that I had a bad flu but I would be okay. He was so wrong.

The day she took me to the hospital, I had been lying on the living room couch. My mother had come over and sat down next to me. “How’s my sweetie?” she asked. I shook my head. She kissed me on the forehead and then went into the kitchen to talk to my father. “Bill, call the babysitter to cancel,” she said. “We can’t go out tonight.” They had theater tickets for a show that was playing in Chicago. My mother came back to me and took me upstairs to my room. I must have fallen asleep because I remember waking up, hours later, and feeling like I was going to die. I called my mother. She came running into my room. “Mom, I don’t feel good,” I told her.

“Can you put your chin to your chest?”

“It hurts,” I told her, after trying. She couldn’t remember how she knew to ask that question, but remembered that if the answer was no, it was a very bad sign. I was wearing my favorite pink-and-white pajamas, and she picked me up, wrapped me in a blanket, and then took me to the hospital while my father stayed home with my brother, Bryan, who was a year and a half younger than me. The doctor who admitted me said that it looked like I had spinal meningitis, but that the spinal tap would confirm his diagnosis.

About an hour after my mother heard me scream, the doctor came into the waiting room to talk to her. “Mrs. Sculthorpe, please sit down.” My mother’s heart skipped a beat. “It is spinal meningitis—a very bad case. We’re doing everything we can, but you need to be prepared. We’re not sure if she’ll make it through the night.”

That’s when my mother turned to the doctor and said, “She will not die, doctor. She will not die.” Years later, those words would make me stronger.

They put me in isolation and gave my mother a gown and mask to put on before coming to my room. A profoundly spiritual woman, that night she felt betrayed by God. Where are you? she asked him silently. Why is this happening? Why are you letting this happen? She sat in my room and wept for hours, holding my hand.

The night passed. I didn’t die. Then the next passed. When it started to look as if I were going to live, the question then became what havoc the illness would wreak upon my body. Deafness, epilepsy, blindness, or any combination of the three were all possibilities, the doctors said. My parents were just relieved that I wasn’t going to die.

But the horror continued.

For fifteen days, I drifted in and out of sleep, the little veins in my arms collapsing from the IVs, so they had to put them between my toes and in my feet, with my mother still asking God, Why?

Finally, one sunny morning, I awakened. My father came over and sat on my bed and started talking to me. He was telling me about all of the people who had said hello, saying, “Heather and Heidi [my twin cousins], Grandma, Aunt Linda, Uncle Jerry, Doris . . .” I understood him until he got to my cousin Doris, and then I asked, “Who?” He thought that I didn’t remember who Doris was, but that wasn’t it at all—I didn’t recognize the shapes his mouth was forming. At that moment, I experienced a strange sensation of silence and knew that something wasn’t right. It’s my most vivid memory from that time because it was when I first realized that I could not hear. Finally, when I understood “Doris,” we moved on.

From that moment on, lipreading became my way of “listening” to people. The adjustment happened so quickly, seamlessly, and matter-of-factly that I don’t even remember missing hearing people’s voices—or at least, I didn’t allow myself to. I don’t think that I was lipreading right off the bat, yet I don’t remember struggling with the sudden loss of communication. The inclination to lip-read just took over. Knowing what I do now, I believe that I was in a readied state. It was as if I had been given the talent to lip-read.

Nevertheless, at the time, it was all so confusing. I had been so sick, and this new silence was so strange that I didn’t understand what had happened to me. Looking back, I think that my strong need to survive, to get back to the life I knew as fast as I could, had already kicked in with full force, and I didn’t even fully grasp that I could no longer hear.

My parents, however, were beginning to grasp it. Once or twice, my father talked to me with his back facing toward me, and, of course, I didn’t answer, which keyed him right into what the doctors had said. Then there was the day when he and my mother had arrived at my hospital room around noon, and we spent the afternoon sitting around talking (I got as much of the conversation as I could), watching TV, playing cards, and reading magazines. I also napped for a while and was quickly regaining my strength. Late in the afternoon, one of the window shades in the room suddenly flipped up, making a loud noise—pfpfpf-pfpfpf-pfpfpf. I didn’t stir. My mother, already hypervigilant to my impending symptoms, really became concerned.

An hour later, when the pediatrician came to check on me, she told him how I hadn’t reacted to the loud noise. He put his watch to my ear and asked me what I heard. “Tick tock,” I told him.

“She can hear,” he said.

I don’t remember if I actually heard the sound of the watch, or if I just thought I did—if my brain “heard” the sound because it knew that’s what it was supposed to do. It’s a phenomenon called phantasmal hearing, and it happened again.

I remained at the hospital for another week and then went home. In spite of everything, I wasn’t scared or upset in the hospital or when I came home—just confused because of all the enormous changes.

For example, I quickly learned to rely on vibrations. Whenever my mother was cooking in the kitchen and needed me, she stomped her foot on the floor. I felt it sitting at the kitchen table and looked up, knowing that she wanted to tell me something. Then there were the lights. Whenever I was upstairs in my bedroom and she or my father needed me to come downstairs, they flicked the lights on and off at the bottom of the stairs. I saw the lights flickering in the downstairs hallway and knew to come down. We all quickly adjusted that way.

In spite of all the changes, I don’t think there ever was a particular moment in time when it hit me, “Oh my God, I’m deaf,” and I never talked about it with my parents—or anyone, for that matter—which seems a bit odd to me now. My mother told me, though, that about a month after I had come home from the hospital, she found me sitting on my bedroom floor with my records and record player just watching a record spinning around and around and around. Such stories make me think that if there wasn’t an exact moment in time when I realized I was deaf, it was because I didn’t want there to be.

When I finally did come to the realization that I was deaf—that I couldn’t hear anything—I was mad at my mother, at first, for never having told me that there was such a thing as deafness. What a shock. Not that I was deaf, but that there actually were people who couldn’t hear. I had heard of blind people or of people in wheelchairs, but not deaf people.

Still, after being home from the hospital for just a few days, I was ready for the entire ordeal to be over. I wanted to play with my toys and my friends. I was a child, resilient, living in the moment. I could communicate, read, and write. I wanted go to the pool. I wanted to have fun. My mother thinks that I pretended half the time because I didn’t want her to be upset. But I swear that was not how I experienced it.

During the first few months, she took me to doctors and audiologists in Chicago, thinking that someone would tell her that my hearing would come back and that I’d be okay. But no one did. I remember her dragging me to all those doctor appointments, but I thought that I was just going to get my “ears checked” and was bored to tears. I wanted to be playing outside with my friends instead of sitting there with microphones on my head waiting to raise my hand when I heard something—which I never did. The sounds would get so loud that I felt the vibrations on the earphones or my eardrums would pop. Then I would raise my hand, but I wasn’t actually hearing sounds, just feeling vibrations.

They gave me hearing aids, which never helped. Yet I wore them all through elementary school. In the hearing-impaired classroom, the teacher used a microphone to amplify the sound of her voice. Everyone thought that the hearing aids might help me to hear something. My mother also wanted me to wear them because it let the hearing kids know that I was deaf.

At first, I wore a body hearing aid, which was supposed to be more powerful than the over-the-ear kind. The little doohickey sat in a small, white cotton pouch that was strapped to the middle of my chest. Straps went under my arms and over my shoulders, connecting in the back like a bathing suit. From the front, two wires went up to my ears.

I wore the pouch over my clothing because it always needed adjusting. I remember eating chicken soup a lot and the soup dripping onto the hearing aids and soiling the straps. Later, I wore the pouch under my clothes. I wore it for three years and then switched to an over-the-ear hearing aid, which I lost at O’Hare Airport when someone walked off with my little pocketbook.

Eventually, my mother mourned my hearing loss and everything that came with it, which I believe was so incredibly healthy. However, at first, she worried about how I’d ever survive in the world as a deaf person. She wanted me to be like I was before. She wanted to be able to talk to me and for me to be able to hear her. Turning inward, she asked God to help her to say and do the right things for me; praying pulled her through. Yet she questioned if she believed enough and had enough faith, hoping that if she prayed hard enough, I would get better.

ME AT SIX YEARS OLD WITH HEARING AIDS

At the same time, she was very angry at God because I had become deaf—that he had allowed it to happen. She couldn’t understand why she had experienced so much support from family and friends—that God had been there for her, but not for me.

As a child, had I known how she had suffered over this, I would have told her straight out that I’d never doubted for even a second that God had been with me. And now, as I sit here writing this book, with Zoe asleep in the next room, I know it even more. Years later, my mother would meet deaf adults who were happy and successful and raising families of their own just like hearing people, and it would help her realize that I was going to be just fine. The professionals had told her right from the start that I had a natural talent for lipreading and that not everyone does. This made her feel hopeful. After about a year, she finally accepted that I was deaf; both she and my father took sign language classes and supported me in more ways than I ever could have asked for.

One of my fondest memories is sitting with her in the living room and watching Little House on the Prairie. She interpreted for me in sign language. She sat on the fireplace hearth, and I sat on the floor. That was in third grade. Later, in eighth grade, while she was getting my brother and me off to school every morning before rushing off to work herself, my girlfriends would call to say what they were wearing, which really slowed us down, but she always put up with it and told me, wanting me to feel like I was one of the crowd.

It was different with my dad. He’s less emotional than my mother and more or less deals with things as they come. Of course, he was very saddened that I had lost my hearing, even a bit angry at first as well. It was hard for him to have a hearing daughter one day and deaf the next. I think he was comforted though by how well I seemed to be adjusting. He was proud of me for that. Later he would say that had I been another child, he might have worried more, but that my self-confidence made him confident that things would work out and that I handled everything better than anyone possibly could have. He was also comforted and felt rewarded by the fact that my close friends in the neighborhood just accepted me for who I was and were still my friends. That’s what really let him know that everything was going to be all right.

One of my favorite memories with my dad is going to these father/daughter events called Indian Princesses. Grasping sign language hadn’t come all that easy for him, which I think he may have felt a little bad about, but I remember him interpreting for me at those gatherings. He was Big Feather, and I was Little Feather. I also remember him occasionally taking me to the mall to go clothes shopping. He was never overprotective or anything when we did things together. After a while, for both my parents and for me, my being deaf just became the way it was.

My close friends were very supportive from the start by just being regular with me, which truly meant the world to me. The fact that I was an extremely self-confident child helped me to adjust as well. The only difficulty I had was feeling dizzy the first few weeks after coming home from the hospital, due to an imbalance in my ears. I remember having to crawl around the front yard; it was a bit slanted and was easy for me lose my footing.

At times, I thought I was getting my hearing back—I’d swear that I’d heard something, like the church organ when we went on Sundays and the sound of the waves at the beach when we visited my family in New Jersey. I would hear them crashing inside my head. But it was more phantasmal hearing; ultimately, I always faced the silence. Today I can still remember the sound of that church organ, and the waves crashing, and the sound of paper crumbling, though they grow more and more distant. I have no memory of voices.

The fall after I became deaf, I started first grade in a school that had a deaf program. To maintain my speech, my mother wanted me mainstreamed in a regular classroom with hearing children. I had a resource teacher who worked with me one-on-one. I was the only deaf student in the entire class. I watched the deaf kids in the class next door and copied what they did. Years later, my mother told me that I pretended to sign, using signs that had no meaning, like a child playing make-believe. I also fiddled with my hearing aid wires and the controls. Eventually, it became clear that I needed more support; so in second grade, I finally went into a deaf class and loved it.

It was an “oral” class, meaning that the teacher spoke and didn’t use sign language. We read her lips, so I continued using my speech, as my mother had wanted (as do most hearing parents who have a deaf child). I had already grasped the essentials of English: pronunciation, syntax, inflexion, even idioms, which had all come by ear. I had the basis of a vocabulary, which would only be enhanced by reading, and I continued reading at home with my parents. There were only three students in the class—Tom Halik and Tommy Miller, who could both hear a bit and had spoken language, and completely deaf me. Every day, I’d watch our teacher, Mrs. Kutz—with her long black hair cut in a feathered, wispy style and her huge smile—write on the overhead projector (this allowed us to absorb things by having the benefit of a visual aid) and read her lips all day long.

It was then that I became more aware that I was different. In first grade, I had done pretty much whatever the other kids did, but with the work becoming more academic, I began realizing that I was missing directions and puzzled about some of the assignments. Mrs. Kutz discovered that I couldn’t spell well and began giving me additional help.

The class next door to mine was for the deaf kids who used sign language and didn’t use their voices at all; they were students who were born deaf or who had lost their hearing prelingually (the more common scenario compared to mine).

Those were the kids who taught me how to sign.

I had started picking it up from them from the moment I’d started school—at recess, in gym, and while sitting with them on the school bus day after day after day. By the end of first grade, I was signing right along with them.

In fourth grade, I finally made my first deaf girlfriend, Lisa, and it was a big deal to me. Other than the kids at school, I played with my hearing friends from the neighborhood. Even though Lisa and I spoke in class, we signed when we played together. I remember the day my father drove me to Lisa’s house for the first time my mother was just overjoyed.

It’s amazing to me now when I remember that when Lisa and I played together, we couldn’t watch television or go to the movies. (Today, it’s hard to imagine Zoe not in front of the TV.) But closed-captioning wasn’t available then; it didn’t become widely available until the early 1990s. Lisa and I couldn’t even listen to music. But life was good.

There were challenges. Once, I was left in the stacks of the school library during a fire drill. There were childhood trials. Even though my closest friends remained true, other kids teased me. The kids in the playground made fun of the way I talked. (Not being able to hear my own voice impacted my speech.) Once, a kid asked me if my hearing aids went through my head. “Yeah, right through my braaain,” I told him, thinking what a jerk he was. Some kids didn’t even believe I was deaf, so I took them to my house to show them the “Caution, Deaf Child” sign that my mother had put on the front lawn.

I hated that sign with a vengeance. “Why do I need a sign to tell cars about me?” I wanted to know. My mother just wanted them to slow down, of course. What I hated most was riding in the bus for “special needs” kids, which the year before my friends and I had named the “baby” bus. It was half the size of the regular bus. Other people may have thought I was different, but to me, I was still the same. I wasn’t handicapped or special, and I certainly didn’t need a sign or a baby bus. I didn’t want to be different, and I didn’t want to be labeled. Yet, even though I was unable to express those concerns, I was more upset by them than by the fact that I was deaf.

In third grade, we got a new swim coach. Even though none of my previous swim coaches had ever coached a deaf kid before, this coach was so closed-minded and was very uncomfortable around me; he honestly believed that my being deaf limited my swimming ability. He took me out of the lineup, which really angered and humiliated me because I had never been behind with my start: I would wait for the smoke to appear from the starting gun when it went off, and then, bam, I was off. I was one of the best backstroke swimmers and had been on the swim team every summer. It was the first time that anyone had made me feel like a second-class citizen because I was deaf. Fortunately, my mother spoke to the coach, he put me back in the lineup, and things worked out after that.

Despite the few mishaps, I had adjusted very well to being deaf. I was succeeding academically, I had become a good lip-reader and signer, and I still had speech. Even though a few kids in the playground wouldn’t play with me anymore, I was thriving socially; when my deaf friends weren’t at my house playing, my hearing friends were. I was part of the crowd and having fun, doing homework, and joining in after-school activities. My desire to do well, be accepted, and please others, such as my parents and teachers, especially since becoming deaf, also helped—as did my self-confidence.

Who knows whether that confidence came from an intense drive to do my best or from my connection with God and knowing that I’d be taken care of. One way or another, I’ve just always been that way. We went to an Episcopal church at the time (later, after my parents divorced, we switched to a Lutheran one), but it was my own individual connection to God that nurtured me and allowed me to become strong. Somehow, I always wanted to be better than average and to do something first class with my life. Becoming deaf might have traumatized another child, but not me; I think that it has made me a better person. It has forced me to raise the bar in everything I do and has helped me to become more self-aware, giving me the opportunity to go beyond my comfort level, be less prejudiced, and relate well to people who are “different.”

Facing such a huge loss at a young age forced me to see how people treat one another and what it’s like to grow up in America as part of a minority. The experience also gave me a different perspective on living with the majority—being deaf in a hearing world. My world was silent. I was cut off from communicating and had to learn to survive through that.

The world operates through spoken language. I had to think ahead, be more aware, be more alert, and take on challenges I might not otherwise have taken on. Today, I can’t listen to the radio as I drive to work in the morning; hear announcements over a PA system; or, if it isn’t captioned, watch TV. Often, because of communication barriers, I have to work twice as hard as a hearing person. Instead of it taking me five minutes to make a doctor’s appointment, it takes me ten.

At home, I use a videophone to make phone calls. When I am talking with a deaf person, I see them signing to me on a screen. It’s sort of like Skyping; we just sign back and forth to each other. To connect with people who don’t have a videophone, I use something called Video Relay Service. So when making a doctor’s appointment, for example, I sign to a video relay interpreter I see on my screen, who then interprets what I said for the nurse on a telephone.

It takes extra time. First, I have to make sure that the interpreter is voicing for me correctly so that the nurse is getting the correct information, which I do by reading their lips. Then, I have to request that an interpreter is present at the appointment, and if the nurse isn’t familiar with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), I have to educate her that this is my right. It’s like that for deaf people in the mainstream. By now, of course, living that way has become second nature. I don’t even think about it.

Back then, I started compensating without thinking much about it either. It was funny. When I first became deaf, people started treating me differently, although I still felt like I was just like everyone else. But as time passed, the reverse happened. My family and friends in the neighborhood told me that despite my being deaf, I functioned just fine, that it seemed as though I were hearing, and that I was bright and could make it in the hearing world. They said that I didn’t need to be with deaf people at all. Yet, even though I inherently knew that what they were saying was wrong, that being deaf did make me different, even with all my confidence—I tried so hard to convince myself that what they were saying was true. I really took what they said to heart.

While I had some deaf friends at school, at home, I usually socialized with the hearing kids in my neighborhood and was the only deaf kid in the whole group. One of my best friends was a girl named Chris D’Alessandro, who lived down the block from me. Even though Chris was a year older than I was and was a grade ahead of me in school, we hung out after school and on the weekends. She quickly learned how to sign and became my advocate and champion. Chris made sure that I was included in all the conversations with our gang, and she called my mother on the phone to coordinate our plans for me. I was more grateful to her than I could say.

When I entered junior high, even though I was mainstreamed in a public school that had a deaf program, I chose not to participate in the deaf classes most of the time. I took regular classes and had a sign-language interpreter with me throughout the day.

I thought I was too smart for the deaf classes.

I didn’t know that deaf kids who are only exposed to sign language and don’t use any speech whatsoever—like the kids in the class next door to me in elementary school—often read below grade level because their English isn’t honed. Mistakenly, I associated reading below grade level as being less intelligent. Most of those kids didn’t speak either, which I also mistook as a sign of being less smart. I sure was wrong.

In eighth grade, the pull to prove to myself and everyone else that I could “stay hearing” was stronger than ever. I left the deaf program altogether and transferred to my neighborhood junior high school, which was right up the street and where all of my hearing friends went. I didn’t want to be in a “special” school anymore. I wanted to walk to school with my friends and be a part of it all. I was the only deaf student in the entire school, and they gave me a full-time interpreter named Joyce Zimmerman. Joyce sat near my desk in every class and interpreted for me. She was awesome because she blended in, giving me space when I needed it, but was always there when I needed her. She would meet me at each class but did not follow me there. She let me be independent and did not come to recess or lunch.

That year, I became president of the student council. When I first ran for office, I read my speech over the intercom and then had a friend reread it to be sure that everyone understood. Once elected, I used my voice to run meetings and do other things; Joyce would sign to me what people said. In ninth grade, I remained local as well, attending Naperville Central High School with my neighborhood friends and, again, was the only deaf student in the school.

That was the year when things really began changing for me.

Central High had so many more students and teachers than my previous schools, none of whom knew me or my family. Despite having my friends there, who were as welcoming as usual, and Joyce, who interpreted for me all throughout high school, I began feeling very isolated. My self-inflicted pressure to stay hearing still remained in full force and began taking its toll on me. Chris still had very high expectations of me, and because she was older than me, I looked up to her. She really believed I could be successful in the mainstream and continued to support my success. I would hear her voice in my head saying, “You’re not different; you can do it!” I didn’t want to let her down or let myself down. I was proud of myself for being able to manage in that hearing world and in a hearing high school, and that pride felt good.

It was the era of Flashdance, and, believe me, I knew what was “in” with those hearing girls. Chris made sure of that. We went to see Rocky when it first came out, and she taught me the popular song from the movie, “The Eye of the Tiger.” She would tap the beat on my leg, and I mouthed the words. In the same way, my hearing friends taught me all the popular songs of the time: “Last Dance,” “Hard to Say I’m Sorry,” “Time for Me to Fly.” I so appreciated them for teaching me those songs because it made me feel like I was part of the group.

But life was a mixed bag. I was missing things. At the Lutheran Church, I didn’t have an interpreter, so during my confirmation classes, I had no idea what was going on when they read from the Bible. I just sat there, wondering what was happening in the silence. Later on, my interpreter from school, Joyce, joined my church, so I got lucky.

Once during summer vacation, I went to the movies with my twin cousins, Heather and Heidi. They were identical twins, beautiful girls with dark brown hair. They were my age, and we had grown up together. To them, I was just Brandi, their cousin, not Brandi, the deaf girl. I had gone to the movies a few times with my father—who was an avid James Bond fan. The movies were heavy-duty action and easy to follow, so I was looking forward to going with my cousins. Heather and Heidi were the most fun people for me to hang around with—always daring and getting into trouble. We fed each other popcorn and had sodas. We had gone to see the Chevy Chase movie National Lampoon’s Vacation (which wasn’t closed-captioned, of course).

Perhaps it was because of the amount of dialogue, but I didn’t understand a thing. What’s so funny? I thought. As I watched my cousins laugh, while I sat there in silence, I was painfully reminded that my hearing was not what it was supposed to be. I was beginning to feel very different and alone.

The thing about lipreading is this: even though I’m very good at it, at best I can only follow 50 percent of what’s going on, which is usually enough for me to get the gist of the conversation and respond appropriately, but sometimes it isn’t. One-on-one, I communicated very well. I did fine. But in a group, it became impossible to lip-read what everybody was saying. At night, it really became difficult when I couldn’t see my friends’ faces. Yet, I thought about my deaf friends, over there in the deaf program, whom I saw on the weekends and at other times, playing around and having fun with deaf people whom I hadn’t met yet, and I started longing to be a part of that.

I was caught between two realities, yearning for fuller communication and to be around deaf people, yet feeling that gigantic pull toward the hearing world; my friends’ and family’s influence on me was just so huge. I knew that they were all well intentioned when they told me that I was fine in the hearing world. But deep inside, I began feeling more and more that I was different and functioned differently than they did, and that they were so wrong.