Читать книгу Finding Zoe - Gail Harris - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter Two

CHANGED BY A DEAF PRIEST

THE SPRING OF 1984, toward the end of my freshman year, was brutal. Torn between wanting to stay in the hearing world and yearning for a fuller connection with deaf people, I realized I needed to decide whether to stay at Central High or transfer the following fall to Hinsdale South, which had a deaf program and was thirty minutes from my home. When I mentioned it to Chris, she was extremely disappointed that I would even consider Hinsdale South. She just genuinely believed that Central was the best place for me and that I could make it there.

I agonized over the decision for weeks; no one knew what I was going through, not even my mother. I couldn’t express it, but at fifteen years old, I knew that I wasn’t just choosing a school—I was choosing a life. Staying at Central meant I’d probably go to a college such as Illinois State with my friends, marry hearing, and remain in that world. Going to Hinsdale South meant I’d probably go to Gallaudet University or National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), marry a deaf person, and be in the Deaf World. Being on the fence—dabbling in both worlds but never fully embracing either—no longer felt tolerable.

It was an overwhelming decision, yet my heart knew the answer—and had known it all along. I finally chose Hinsdale South and that year said good-bye to my hearing friends from the neighborhood. I couldn’t articulate to them why I was leaving; I just told them that I was going to South, to the deaf program. I didn’t know how to say that I felt tired and defeated from playing a game I knew I couldn’t win and wasn’t good for me anyway. How could I tell them that I was mourning the life I had known since I was six, or that the things I had done had been fun and had served me well but could no longer lead me where I needed to go? On some level, I think they understood. After that, I only saw them when we bumped into one another on the street, and it was always bittersweet.

I’d made my decision in the spring but avoided telling Chris until school was almost out. I was too scared to tell her, for fear of disappointing her. Carrying that pressure around inside me all that time felt awful. I think she knew I was avoiding her. I remember the day I finally told her very well. I went to her house, and, through my tears, told her that I was leaving Central. She ended up being more upset that I had been so scared to tell her. She said that it was okay, that what was important was that I had “tried.” I walked home feeling so much lighter. I knew then that I was really done with that part of my life—and I wasn’t looking back.

I had no regrets, but it was tough. Half of it was that I thought I would miss my friends and that I was disappointing them, which was devastating. But the other half, which I was finally acknowledging, was that I felt like they had disappointed me by telling me I was someone I wasn’t, by saying that I could function as a hearing person, and by making me feel that I wasn’t meeting their standards. I was very hard on myself, striving to stand tall, and yet I felt as if I had failed in their eyes.

I prayed to find peace with my decision, find acceptance and peace with myself. I needed peace with my life, my family, my neighborhood friends, and the world. Although I didn’t agree with everyone’s claim that I was normal like them, I wasn’t savvy enough to explain to them how I felt or what I needed. I wasn’t able to say that even though I walked down the hallways in school with a big smile on my face, a deep-down part of me wanted to curl up in the corner and have everybody leave me alone. I remember walking over to the cornfields about a block from my house one day and just sitting there, in the middle of the stalks, trying to come to terms with it all. I was longing to hear some wisdom that would help me see the light. I didn’t want to feel like the lone soldier out there.

I arrived at Hinsdale South and loved it. The school had 2,000 hearing students and 150 deaf students—so many more than in elementary school and junior high, as the deaf kids from each district came to Hinsdale. They all took classes in the deaf wing—except me. Even after making the huge decision to switch schools, I still avoided the deaf program and took all my core classes with the hearing kids, with the use of a sign language interpreter. Part of me still believed that I was smarter than the other deaf students, and I still needed to cling to what was familiar and to what I thought people expected of me. I was still entrenched in the hearing world and was not ready to loosen the ties.

Even so, I took a few classes with the deaf kids, like Health and Consumer Education, and these classes ended up being my favorites. I just loved the direct communication and soaked it in; it was so much more fulfilling than finding out what was going on through an interpreter. I socialized with the deaf kids at lunch, in gym class, and after school, as well, becoming part of a group and the culture I craved.

The summer between my sophomore and junior years, twenty of us went to a deaf camp in the Adirondack Mountains in Upstate New York; we all took the bus there together. This Catholic camp, called Camp Mark Seven, was run by a deaf priest named Father Tom. I had no expectations—my friends were going, so I went along. We arrived right before dinnertime and checked into our dorms.

Whoa. I had walked into a different world, into Deaf Culture, and into the Deaf community.

Everyone there was either deaf or they signed—the counselors, cooks, maintenance people, lifeguards—right down to the nurse. It wasn’t participating in the camp activities with my deaf friends that made the difference—I’d done lots of activities with them at school—the difference was that the entire staff was also deaf. Until that time, I had never really interacted with a single deaf adult. These days, it’s different; but back in the 1980s, most teachers for the deaf, like those at South, were hearing. My parents and relatives were all hearing. In the Deaf Culture, we talk about the 90 percent rule: 90 percent of deaf parents have hearing children, and 90 percent of deaf children have hearing parents. Over the years, I’ve met deaf children who thought they were going to die by the time they reached eighteen because they had never met a deaf adult. Many certainly don’t believe they can make it in the general culture.

It was as if I could finally believe in my future.

For the first time since I was six years old, I was signing with deaf adults in an environment where communication was 100 percent accessible to me. I had full communication. No more missing out on parts of conversations; no more feeling like I wasn’t being understood. For two whole weeks, I was smack in the middle of everything and soaked it up like nothing before—helping out in the mess hall and making meals with George the cook, and helping the lifeguard put away the pool chairs. When I rode home on the bus two weeks later, I immediately felt like my communication was gone—like the air was just being sucked out of me.

My camp counselor, Carla, was a psychology major at Gallaudet College (later called Gallaudet University). She had an air of confidence about her—she was independent and had dreams of her own; having that camper-counselor relationship with her allowed me to see beyond Naperville and Hinsdale South and realize that there was a life out there waiting for me. Even though we rarely talked specifically about being deaf, I never forgot the time we did because her words have become my mantra for raising Zoe. We were sitting by the archery court one afternoon.

“You think much about being deaf?” I asked.

“You mean how it impacts your life and stuff?”

“Yeah,” I said.

“Not really,” Carla said. “I learned long ago that you need to make it your friend—you won’t get through life if you don’t.”

“Hmm . . . never thought about it that way.”

“Yeah, Brandi,” she said. “Whatever you do, you have to embrace that you are deaf, but don’t ever let it define you.”

The camp was called Mark Seven because in the Bible, Mark 7 references Jesus healing a deaf person. I remember Father Tom telling us those particular verses—verses 7:31, 34, and 35. All of the campers were sitting down by the lake with the tall trees surrounding its circumference and providing shade, where every morning he gave his daily sermons and workshops; the outdoors was our chapel.

“Jesus heals a deaf man,” he signed, his round-rimmed glasses reflecting the sunlight. “Looking up to heaven, he sighed and said, Ephphatha, which means, ‘Be opened.’ Instantly the man could hear perfectly, and his tongue was freed so he could speak plainly.” He continued, “Ephphatha means empathy—be thou open. When Jesus said it to the deaf man, it meant, ‘open your ears and you become hearing.’”

A chill went up my spine. Immediately, I understood, “Be thou open,” to mean: be open to life, to people, to ideas; be accepting. Don’t judge. Already I knew that I was more open and accepting of others than most—like a mother figure—although I was too young then to realize that it was because of having experienced my own loss, of having become deaf. By fifth grade, I was able to discern what people were really thinking, yet not judge them. Even though I hadn’t walked in their shoes, I could understand them and what they were about. I’d made fun of the kids who were riding the “baby” bus one year, and the next, I was riding it myself. Although I couldn’t articulate these thoughts back then, on some level, I grasped that people’s differences added richness and soul to life and to being human. Hearing Father Tom’s words that day helped me to understand that a little bit better.

Late one afternoon, Father Tom was talking to us down by the water, his straight, dark brown hair looking jet black, with the sun hiding behind the trees. He had a medium build and was wearing black pants and a paisley green shirt.

“How many of you are proud to be deaf?” he asked, in his kind and unassuming manner.

No one raised their hand. I remember thinking, This man is crazy.

He continued on, “It was a difficult job for God to make people because he had to give each person a completely different personality and appearance.” He thought for a second and then continued signing. “So, to make it easier for himself, he made one recipe for the human body.”

I sat there, listening intently.

“Yet, he made a different body recipe, a special one, for deaf people. God put more effort into making this unique group of people,” he said. “Being deaf is a gift from God.”

Wham. Bam. I felt like I had been punched in the stomach.

It wasn’t that I heard him say to me that being deaf is a gift from God, but that being deaf is okay—not only okay but something good, if I let it be!

Nobody had ever said that to me before. Oh, I’m sure that my parents, friends, and teachers wanted me to generally feel good about myself. But Father Tom’s words validated my very existence as a deaf person. They were a lifeline connecting me to Me, helping me to see that I wasn’t crazy for feeling different, that I felt different because, good God, I was different, and nothing that anybody could say would ever again make me believe otherwise.

My new awareness was shaky, like a foal first standing on its legs, but that afternoon a window had opened, and I saw that being deaf was the way I was meant to be. At that moment, I knew that going back to Central High for that first year had been a wasted year; I had been trying to prove to everyone that I was hearing, instead of knowing that being deaf was okay.

I realized that I had a choice: I could continue trying to be “hearing” (having hearing friends and taking hearing classes) and fail, or I could be the best deaf person I could be. It was then that I began seeing my being deaf through the eyes of self-acceptance and understanding that it didn’t mean I was failing.

After returning home from camp, I got a job at the Colonial Ice Cream Shop. I worked fountain and just loved eating the ice cream and making all those sundaes. The “Turtle” was made from two pumps of hot fudge, one pump of caramel, and pecans over vanilla ice cream. Another popular sundae, the “E.T.,” named after the movie released that summer, was made from one pump of peanut butter, two pumps of hot fudge, and Reese’s Pieces over vanilla ice cream.

It was at the Colonial that I fell for a hearing guy, and fell hard, beginning a love affair that ultimately led me to discover my deep capacity to give and to receive love. My very first day on the job, Matt came right over to me and said, “Hey gorgeous,” and I thought, Hey gorgeous, yourself.

Matt was seventeen; he was tall with dark brown, curly hair and green eyes and was as kind as he was versatile. He not only worked fountain with me but also did just about every other job in the joint—host, cook, waiter, supervisor. He was different from the crowd: steady, responsible, and loved having a good time. As soon as we began hanging around together, he learned to finger spell (signing words, letter by letter). Then, he bought The Joy of Signing, a popular book back then, and studied signing with a vengeance, picking it up quickly, which I really appreciated.

Occasionally, it was Matt’s job to lock up the shop at night after everyone had gone home. I’d hang around, so it was just the two of us there all alone at midnight. He’d whip up a couple of Monte Cristos or patty melts, and we’d sit at a booth and eat. I brought my great-grandmother’s sterling silver candlesticks from home, which we hid in the ceiling right above the booth and took down whenever we dined.

But Matt’s love notes were what I appreciated most of all; they made me fall in love with him. Every night around midnight, when I wasn’t at the restaurant with him, he’d drive by my house on the way home from work and leave me a letter in my mailbox. Some were strictly love letters; others were his thoughts about his day and other musings; we couldn’t communicate by phone, so letter writing took its place. First thing every morning, I ran to the mailbox to get his note, and then I’d write back, leaving my note in the mailbox in the afternoon for him to pick up that evening. Rather than receiving phone calls from my boyfriend, like hearing girls did, I received his amazing love letters. For once, being deaf had its privileges, and it was my secret—receiving little treasures that the hearing girls would never know . . . a whole box full of them. Matt had a way with words that went straight to the heart.

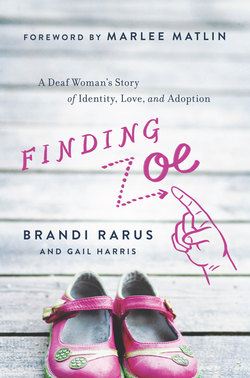

Summer turned to fall, and once school started, my life was very full. Besides spending time with Matt, my horizons expanded in the deaf circles when I played the role of Lydia in the Chicago stage production of Children of a Lesser God and became Marlee Matlin’s understudy. Lydia wasn’t the lead role; she was one of the students at the school for the deaf. The Immediate Theater Company—an off-Broadway-caliber company—had been looking for someone to play the role and saw me perform it in our high school’s performance of the show, which they came to scout. (Throughout the years, I had participated in “Deaf Drama” as an extracurricular school activity.) The company offered me the role without even auditioning. However, my mother made me turn it down because she thought that it would place too big of a burden on my school schedule. But she agreed to let me be Marlee Matlin’s understudy.

ME AND MATT AT MY SENIOR PROM

When the show ran that summer, Marlee was in the middle of callbacks for the movie for the lead role of Sarah and was gone quite a bit, so I got to perform several times. Back then I did it just for fun. However, I can see now how acting on stage before hundreds of people in the role of a deaf character was a step toward later being on stage before thousands of people representing deafness for real.

From the outside, my life was good; I had a fun job, a great boyfriend, and tons of friends, and I was performing—but on the inside, it was altogether different. Camp had begun my journey toward self-acceptance, but by being with Matt all the time, working at the Colonial, living with my hearing family, and still taking the hearing classes at school, I remained that hearing girl at heart, while my struggles continued to grow.

At Matt’s graduation party at his parents’ home, he was busy entertaining and couldn’t be with me very much, and I felt uncomfortable in the crowd. The same thing occurred at his grandmother’s Thanksgiving dinner: I felt so out of place at that table. Even working at the Colonial—something that I had enjoyed immensely—became more difficult for me to handle. Yes, one-on-one my lipreading was good, but the Colonial was a busy place; usually there were too many conversations happening at once. And just because I could easily talk to a single individual does not mean that people would take the time to talk to me; and when they did, it was usually to give me instructions, not make social talk. That is a big difference. Feeling increasingly left out of the social scene and more and more isolated, having Matt around was my saving grace.

When it came time to choose a college, I went where my deaf friends were going: the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), which is part of the Rochester Institute of Technology (RIT) and is located in Upstate New York. NTID attracted deaf students like me who came from hearing families, had been mainstreamed in public school, and were “oral.”

My other option, Gallaudet University, which is located in Washington, DC, had offered me early acceptance beginning January of that year, but I turned it down, wanting to finish high school with my friends and also wanting to have that time with Matt. In addition, because of my limited interactions with deaf people and my misconception that deaf people who don’t speak are not as smart as deaf people who do, I felt that Gallaudet, which tended to attract deaf people who signed and didn’t speak, would not be academically challenging. No one had ever explained to me that the deaf kids who don’t speak, don’t do so because they weren’t exposed to any language whatsoever until they were toddlers—neither sign language nor a spoken language—and that affects their ability to learn. I didn’t know that they were no less smart than the deaf kids who spoke, like me.

This was often the case with deaf children who had hearing parents (which is 90% of all deaf children). Things today are different, but in the past, a child’s deafness often wasn’t discovered until the child was diagnosed with a language delay at two or three years old. By that time, the child has gone years without any language whatsoever, which can be detrimental to the child’s ability to learn.

In contrast, deaf kids born to deaf parents are usually exposed to ASL from birth, just like hearing kids are exposed to a spoken language, and they are academically on par with hearing kids or deaf kids like me who were exposed to language early on.

At the time, I didn’t even realize that Gallaudet was known as the Harvard of deaf universities! At that time, Gallaudet primarily attracted deaf students who had been exposed to sign language from birth, who, unlike me, came from deaf families, and who were part of the Deaf community and Deaf Culture. Instead of going to public school, these students were often sent by their parents to residential schools for the deaf, or stay-away schools. Living in the dorms with the other deaf students and being with deaf teachers and other deaf adults, they grew up immersed in Deaf Culture and ASL.

When I arrived at NTID, it felt like Camp Mark Seven to the nth degree. I was in heaven—an entire university filled with deaf students for me to meet, hang out with, and learn from. I was back in a communication-accessible environment twenty-four hours a day; I had arrived. There were deaf dorms, professors, staff, counselors, RAs, organizations, parties, sororities, fraternities—2,000 deaf people, just like me, who brought their “being deaf” with them to explore and cultivate. I had found my niche: people to whom I could relate on all levels, people who had pride in themselves and their culture, and people whose culture was so important to them that they were full-force with it, wanting to support others on their journeys as well.

Even though most of us at NTID hadn’t grown up in the Deaf community, the bond and the understanding that we all shared allowed the Deaf Culture, which we had longed for, to be easily cultivated and expressed. We inhaled it. Discovering that deafness wasn’t our enemy nurtured our sense of self-acceptance and belonging. Classes and workshops on deaf-related issues and support from deaf professors helped us find our place within the Deaf community. In that milieu, I continued to evaluate myself.

My struggles with trying to fit in but feeling different in the hearing community had fueled my lifelong desire to be the best—not the best in relation to others, but the best that I could be. Now I believed that I had the best—the best communication, friends, teachers—everything. I was driven, aware that I was changing, but I knew that the change wasn’t complete yet. I quickly became a member of the NTID Student Council. I was being propelled onward—the pull toward accepting being deaf was increasing by multitudes.

Yet, I was also in a major identity crisis, feeling angry and rebellious at my family and Matt, whom I felt didn’t understand what it was like to be deaf or how important being deaf was to me. To be fair, even back in high school, I never let Matt understand, believing that if I really let go and fully embraced that I was deaf—if I went all the way and had more deaf friends and signed rather than spoke—he wouldn’t be comfortable with that part of me and wouldn’t want to spend his life dealing with my issues, my causes, and my world. I just focused on the present. I was on the crest of a wave, feeling stronger than ever before, yet still not accepting of those whom I felt didn’t understand me and had let me down.

When I first arrived at NTID, I was carried away with being away from home. Immersed in this newfound world, it was easy to let Matt slip from my mind. I didn’t write him a single letter, and on Labor Day weekend, after having to practically force myself to go home, I saw him even though I didn’t want to, and he felt my distance. Then, I played hard back at school until Thanksgiving break, when I came home and wanted to patch things up between us. But when he picked me up and we got into his car, I could tell that he wasn’t himself. He was angry at me for “disappearing for months,” and told me he had started dating another girl.

“It’s different. We have our song,” he said. “I really enjoy listening to the radio with her, listening to music . . .”

His words made me sick to my stomach, but I didn’t say a word.

Looking back, I know that Matt didn’t mean to hurt me with his comments, yet it shook me to the core because it was a sobering reminder to me that we were different. He was hearing and had the right to be hearing and enjoy those things—he deserved that. He didn’t have to be dragged into my Deaf World and my deaf issues. He had a right to his life, as much as I had the right to mine. Even though his words felt like a slick kick in the face, they helped me to face my own truth. Never had I felt such power, yet such pain; in order to love myself, I had to lose the one I loved.

When summer came, I wrote Matt a letter; here’s the gist of it:

Matt, I will always love you. But as I’ve grown up and entered the world, on my own, my choices for myself have changed. I am now part of the Deaf community and need a partner to share it all with me. I no longer want to stare at conversations I don’t understand because people don’t sign. I don’t want to spend holidays at a dinner table all alone in my own world because I am not following the conversations. I no longer want to feel this terrible pull between my love for you and a world that you are not part of. Nor do I want to force you to accept a world that is not yours.

I hope that my community makes its own headlines someday, and that Deaf rights are pushed to the forefront, as we demand more awareness. Perhaps you’ll read about us in the newspaper or a magazine—and even meet another deaf person. Then you might understand why it was all so important to me, and even be glad that you were not there. Brandi