Читать книгу Tranquility Lost - Gary Steeves - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword by Cliff Andstein

Оглавление“In every Ministry, in every government office, in every crown corporation and in every public body, restraint measures will be taken.”

With these words on July 7, 1983, while introducing his budget, Social Credit finance minister Hugh Curtis launched a neoliberal attack on the human, social, union and other rights of British Columbians. The twenty-six bills introduced that day broke the social contract between the government and people of British Columbia by bringing Reaganism and Thatcherism to the province. No sector or group, except for the corporations and businesspeople, escaped the attack. The poor, children, women, immigrants, unions, the disabled and the elderly saw their fundamental rights weakened or stripped in one of the most vicious right-wing attacks by a government since the Depression.

People of the province were in shock. Within days, protests were organized. Six thousand people attended a rally in Victoria organized by the BC Federation of Labour and the BC Government Employees’ Union. The protests grew throughout July. Twenty-five thousand “massed in fury” according to the Victoria Times Colonist and within a few days, twenty thousand gathered in Vancouver. Virtually every community in the province saw protest marches or demonstrations against the government’s legislation. While they were being organized, an unplanned event took place in Tranquille institution for people with intellectual and developmental issues.

As part of its restraint program, the government downsized or closed institutions that provided services such as those delivered at Tranquille, or geriatric or mental health institutions. The move was cloaked in language suggesting these closures were to replace outdated institutions with contemporary community facilities and resources. The truth is the community resources simply did not exist. The BCGEU, which represented the majority of the workers at Tranquille, received an invitation in mid-July from the Ministry of Human Resources to attend a meeting to discuss “Tranquille.” No further information was provided.

Gary Steeves attended this meeting and was shocked by the announcement that the ten-year plan for phasing out Tranquille by 1991 was now accelerated to 1984, just one year away. Additionally, the union was threatened with the removal of the collective agreement language that dealt with closures and redundancies. The ministry officials said they would invoke two of the pieces of legislation, Bills 2 and 3, which stripped the union’s master agreement of those protections. The union representatives were stunned.

The meeting set off a chain of events that helped mobilize and inspire people around British Columbia as they began organizing to fight back against the government. Steeves flew to Kamloops to speak to BCGEU membership at 11 p.m. that night. Most stewards and local officers showed up along with many of the union members who worked at the institution. Steeves reported to the three hundred members on the details of the meeting earlier that day. The room became completely silent. He asked them, “Do you want to fight back?”

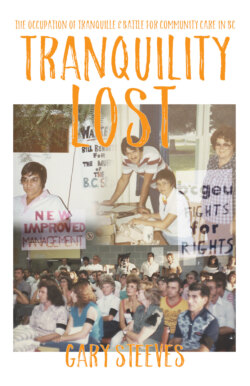

A member stood up and said loud and clear, “We have no choice!” The members in the room erupted into a loud standing ovation and within the hour, plans were made to occupy the institution and place it “under new management” beginning the following day: July 20, 1983. When the occupation of Tranquille was reported in the media later that day, it served as an inspiration to people all over the province that they could fight back. Support for the union and the workers in Tranquille came from all over Canada.

This book is a first-hand account in which Steeves takes us through what it means to occupy and administer a facility housing and serving some of the most vulnerable residents in the province. He begins with a discussion of the development of the healthcare system in British Columbia, the growth of public mental health institutions, the changing attitudes to treatment models and the move away from residential care institutions.

Tranquility Lost tells the story of the occupation and ongoing management of a mental health institution with 600 dedicated staff caring for the 325 residents. Steeves effectively captures the drama of those few weeks at Tranquille in 1983: the excitement of the workers, the anger at government and the commitment of the staff to the residents. This is a compelling story about what can be achieved when workers and their unions fight back against injustice and governments that use the coercive power of legislation.

Cliff Andstein

fomer collective bargaining and arbitration director, BC Government and Service Employees’ Union