Читать книгу Tranquility Lost - Gary Steeves - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter Two The Legislative Assault

ОглавлениеBill Bennett’s confidence was on full display when the legislature opened on June 23, 1983 and did not diminish as Finance Minister Hugh Curtis rose in the legislature shortly after 2 p.m. on Thursday, July 7, 1983 “to present the Government of British Columbia budget for the fiscal year ending March 31, 1984.” It was an annual event where government boasted of its achievements and revealed grand plans for the future. The opposition, for its part, attempted to find as many flaws as possible with the government’s performance and criticize the government’s plans. Opposition criticism that year was focused on the finance minister in particular.

Curtis began by stating that he remained committed to a set of four philosophical principles. None seemed particularly philosophical, but he may have felt the need to sound reasoned and thoughtful. The minister’s approach might seem obvious later. Curtis outlined his “unalterable dedication to the financial accountability of government to the people.” Next, he made a vague pronouncement of being committed to financial responsibility in case anyone thought finance ministers may be committed to irresponsibility. His third commitment was to the principle of fairness. And his fourth and final so-called principle was a commitment “to a government role in the economy which supports private initiative, which provides permanent and rewarding jobs and which builds a secure and prosperous economic future.”

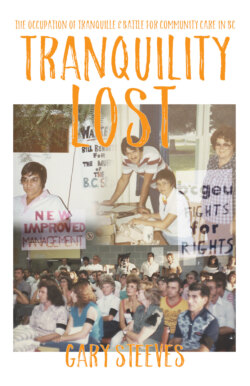

Signs were everywhere during the occupation including this “wanted” poster for Bill Bennett. Gary Steeves

The first three so-called principles—financial accountability, financial responsibility, and fairness—were hardly new or earth-shattering. BC laws generally provided for these notions of public responsibility; Curtis was really reiterating practical considerations for any finance minister. The three were more competency indicators than philosophical debating points. The fourth principle, however, was different. It was more like the Social Credit neoliberal mantra to justify the coming budget as well as previous cabinet decisions like Vote 40. This so-called “principle” was the one that set the direction for the Bill Bennett government and its intention to reshape BC in the image of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. Curtis was trying to establish a rationale for setting aside the public good and government responsibility for British Columbians in favour of corporate welfare and the corporate good as defined by capital markets and Social Credit friends.

Curtis outlined his analysis of the provincial economy since the 1960s. He noted the faltering prosperity and “economic crisis of the past two years.” Recovery, he said, should not and cannot be taken for granted as the problems BC faced today “originated in the social and economic fabric woven through at least two decades of prosperity and social reform.” Curtis was advancing an astonishing twist of logic. He was asserting that the international recession impacting BC was caused by the “prosperity and social reform” advanced by previous BC governments. Hard to believe that a finance minister would make such an argument but Hansard caught it all. According to the finance minister, we were all too prosperous and living too high on the hog while human rights interfered with the entrepreneurial spirit.

Curtis apparently saw no need to notify MLAs that government would, later that day, table its best efforts to eliminate those pesky job-killing social reforms. In detailed and blunt language, he outlined the problem with governments using social or environmental programs to get in the way of private-sector initiative and growth. According to Curtis, public sector employment was a problem in BC and in Canada. Borrowing to finance prosperity was even more problematic, he said, because interest rates “reached levels in excess of 20 percent.” This was especially “devastating” for BC, argued Curtis, because the 1982 Social Credit budget had overestimated revenue by almost $1 billion ($872 million to be precise). The overestimation was not slight, and the reason for this gross overestimation seemed obvious to the opposition. Social Credit wanted to campaign for the May 1983 general election on a balanced budget and needed to overestimate revenue to do so.

The finance minister was lengthy and deliberate in outlining his view of the economic issues facing BC. He noted the provincial gross domestic product “declined by some 7 percent in 1982 compared to a 4.4 percent decline nationally.” Over 200,000 British Columbia workers were unemployed in the winter of 1982–83 with some 162,000 BC workers on UIC benefits. This level of economic displacement had substantially increased income assistance payments which further strained provincial finances. He did not mention the record number of working people trying to pay their mortgage with a 21-percent interest rate and he did not dwell on the budget’s provision for closing Tranquille. Social Credit MLAs applauded his performance.

Opposition finance critic Dave Stupich was a seasoned debater and veteran counterpuncher. Replying to the finance minister’s budget speech on July 8, Stupich was precise in his criticism of the budget: “Never in the history of the province of British Columbia have revenues been overestimated anything in the remote vicinity of the $872 million of the year just concluded.” Stupich questioned the competency of the minister and his advisors as he continued his rebuttal of the Curtis record. How could any competent administration overestimate revenue by almost a billion dollars in one year? This, of course, was at a time when a million dollars was a big-ticket item in a provincial budget. Stupich continued by stating, “On April 5, 1982, the minister of finance had the gall to issue a statement under his name that he had produced an operating budget balanced by revenues. Figures released with the budget yesterday prove the utter falsehood that was presented to the people of British Columbia by the minister of finance on April 5.” Stupich summed up his observations of the budget and those of many observers when he said, “We should all understand the budget to be a manipulation of an election promise.” Curtis had said, “It is time to strive for more with less,” but MLA Stupich mocked the budget, its accuracy and its validity as anything other than a Social Credit fantasy.

The Official Opposition continued to participate in the legislature’s budget debate, probing various areas including issues raised in the election campaign just months before. Stupich pointed out that during the April–May 1983 election campaign, “the premier made vague references to continued restraint. It is also true that the Social Credit Party promised a total of $1.474 billion in new spending.” The contradictions and manipulations in the budget presentation were debated at length and laid before the public for full consideration. Stupich had done his job as finance critic but the government seemed unmoved by fact or passion. They brushed aside the embarrassing truth of revenue deception and political double-talk and ended debate with the adoption of Bill 10 Supply Act (No. 1) 1983. The government had used its majority to approve a total budget of $6.043 billion for 1983–84. Nowhere in that vast sum of money was there any funds allocated for community-based support services for people with developmental disabilities.

The government forged ahead. Late in the afternoon of July 7 after Minister Curtis had completed his speech, the government tabled twenty-five additional pieces of legislation which drew intense legislative scrutiny. The world exploded as the scope and extent of the proposed legislation was revealed. Subsequent legislative debate and private analysis intensified public concern over the government’s direction. The budget bills were a jolt to civil society. They covered virtually every aspect of public sector operation. They tinkered with taxation policy and began the tax shift away from private corporations and onto individual taxpayers. The proposed legislation included Bills 2 and 3, which alarmed the BCGEU to its core.

Bill 2 was formally called the Public Service Labour Relations Amendment Act. It would strip public sector collective agreements of protections and benefits for any worker in that bargaining unit and prohibit negotiations of such benefits in the future. For Tranquille workers, the bill meant they would lose layoff and recall protection, severance pay, job placement rights and a host of other benefits once their BCGEU collective agreements expired on October 31, 1983. It was a stunning piece of legislation that BCGEU analysts concluded would be the end of bona fide collective bargaining in the public sector.

Bill 3 was even more stunning, if that was possible. Called the Public Sector Restraint Act, it proposed to give government and government agencies, boards and commissions (in effect all public sector employers including local governments and school boards) the right to fire any employee without cause and for any reason, including no reason at all. Its application to teachers, hospital workers, school board employees, direct government employees, municipal employees, Crown corporation employees and more was almost beyond comprehension. Polling showed that over two-thirds of the BC public thought the government was wrong to propose the right to fire workers without cause. The measure rubbed the vast majority of British Columbians the wrong way and became one of the loudest protest points in the province-wide Operation Solidarity protest.

As early as the day the legislation was tabled, the telex machine at BCGEU headquarters in Burnaby began spewing copies of termination letters, or notice of termination letters, sent to BCGEU members. I was astonished as the letters came. I knew almost all of the members the letters were addressed to: most were union activists, shop stewards, or local union executive members. I remember the feeling of astonishment at the government for arrogantly acting on a mere proposal before the legislature. And the upheaval and stress it caused in people’s lives was reflected in the phone calls our union staff was receiving.

Gary Steeves, newly hired research officier for the BCGEU, in 1979. BCGEU Archives

There was a host of other proposed legislation including Bill 18, the Pension (Public Service) Amendment Act; Bill 11, the Compensation Stabilization Act; Bill 25, the Harbour Board Repeal Act; Bill 21, the Crown Corporation Reporting Repeal Act; Bill 8, the Alcohol and Drug Commission Repeal Act; Bill 24, the Medical Services Act; Bill 5, the Residential Tenancy Act; Bill 16, the Employment Development Act; Bill 14, the Gasoline (Coloured) Tax Amendment Act; Bill 15, the Social Service Tax Amendment Act; Bill 13, the Tobacco Tax Act 1983; Bill 28, the Provincial Treasury Financing Amendment Act; Bill 4, the Income Tax Amendment Act; Bill 17, the Misc. Statutes (Finance Measures) Amendment Act 1983; Bill 27, the Human Rights Act; Bill 9, the Municipal Amendment Act; Bill 22, the Assessment Amendment Act; Bill 7, the Property Tax Reform Act; Bill 26, the Employment Standards Amendment Act; Bill 20, the College and Institutes Amendment Act; Bill 19, the Institute of Technology Amendment Act; and Bill 6, the Education (Interim) Finance Amendment Act 1983. None of it appeared particularly pro-worker.

The Operation Solidarity (Op Sol) movement was created by the BC Federation of Labour after the government tabled its twenty-six pieces of legislation on July 7. I briefed the Federation’s Public Sector Committee on the afternoon of July 8 on the proposed legislation. The Collective Bargaining and Arbitration Department staff of the BCGEU had analyzed the bills and BCGEU Director Jack Adams, chair of the Fed’s Public Sector Committee, had requested the briefing. The committee developed a strategy to fight the government, which was supported by the Fed through funding of the Op Sol movement. A full strategy eventually included a work stoppage schedule and a general strike of all BC Fed–affiliated unions. General strikes are more common in European countries and quite uncommon in North America. Needless to say, the Fed’s plan of attack on the government’s legislation generated immense media interest.

The legislative landslide caught almost everyone’s attention. The Vancouver bureau of the Globe and Mail carried a two-page spread headlined, “Bennett’s hard line: The 26 bills at centre of storm.” If Bills 2 and 3 were not a strident enough attack on the labour movement, Bennett proposed Bill 27 to abolish the Human Rights Commission and the Human Rights branch of government. It unceremoniously closed hundreds of complaint case files and had security personnel confiscate office keys and escort employees out of their places of employment. On camera, it looked more like a military coup than the smooth operation of a British parliamentary democracy. In the Social Credit mind, tabling the legislation was as good as it being adopted. If Bills 2, 3, 26 and 27 did not catch a broad cross-section of the public’s attention, the proposed phasing out of the provincial residential tenancy branch and the cancellation of assistance to tenants under Bill 5 had a chilling effect on a larger portion of BC citizens. And although one could use the legislative package to create an ever-growing list of aggrieved citizens, Bennett’s government did not seem to care.

The spate of legislation tabled on July 7, 1983 was intended to meet the fundamental objectives for the Bennett government. Social Credit wanted to eliminate or reduce benefits and rights enjoyed by the people of BC. The legislative package would reduce government costs and improve private sector efficiency, they said. It shifted the cost of government onto individual taxpayers and away from private-sector businesses. So much for Curtis’ principle of “fairness” as Canadians already bore two-thirds of the tax burden compared with corporations.

The finance minister had insisted in his July 7 speech to the legislature that “government had grown too large.” To address that situation, Curtis explained in some detail how government was approaching its staffing issues. “From a base of 47,000 FTE [full-time equivalent] staff… authorized in April, 1982, staff reduction plans have brought government ministries down substantially.” “The budget for 1983–84,” he said, “will provide funding for 39,965 FTE staff, with further reductions planned for 1984–85.” He gave as examples the BC Building Corporation, which would be cut by 10 percent, and the government vehicle fleet-management staff, which would be reduced by 20 percent.

Social Credit assumed that tabling the proposed legislation in the legislature meant only the formality of adoption remained. Again, they underestimated the strength of the opposition from the New Democratic Party’s MLAs. The government response to the vigorous opposition to the budget and the accompanying bills was to go to twenty-four-hour-a-day legislative sittings. The extended sittings and the use of closure would force their budget and the proposed legislation through the legislature more quickly. The use of the more draconian parliamentary closure would stifle debate and open the government to further criticism and accusations of undemocratic and dictatorial behaviour.

Denise Lietchfield, healthcare worker and key contributor to the phoning, scheduling and rostering committee. Gary Steeves

The opposition in the legislature would be organized and led by NDP leader Dave Barrett and his caucus leadership team. In a caucus full of veteran MLAs and former cabinet ministers, Barrett appointed a young MLA named Gordon Hanson as Opposition caucus whip. Hanson was from the two-member constituency of Victoria. As whip, he would be responsible for organizing the caucus participation in the round-the-clock, legislation-by-exhaustion marathon brought on by Premier Bennett’s Socreds.

Hanson had received his master’s degree in anthropology from the University of British Columbia and immediately went to work in the provincial museum in Victoria in the early seventies. Dave Barrett’s government was in power and Hanson socialized with NDP political staffers including government caucus research director Mark Holtby. Hanson was approached by a government staffperson about the possibility of going to work in the office of Minister of Consumer Services Phyllis Young. Hanson applied for and was given a leave of absence (LOA) from his position at the museum, then went to work as ministerial assistant to Young for only a few months before Barrett dissolved the legislature and called the 1975 provincial election.

The timing of the 1975 election call has always raised controversy in NDP circles as the Barrett administration had nearly two years left in their legislative mandate. Hanson recalls a story that circulated among legislative staffers. Barrett had asked Provincial Secretary Ernie Hall if he could think of one reason why they should not drop the writ and go to the polls. Hall thought for a second and said, “I can think of fifty-eight thousand reasons.” (The salary of a cabinet minister was $58,000 at the time.)

The legislature was dissolved on November 3, 1975, and Hanson sought and won the NDP nomination in the two-member constituency of Victoria. His running mate Charles Barber was a popular Victoria social activist and musician. On election day, Social Credit’s Sam Bawlf topped the polls with Barber finishing second, just 498 votes behind. Hanson was third, 675 votes behind Barber. With Bawlf and Barber off to the legislature, Hanson was off to the unemployment line. Assistant provincial secretary and deputy to the premier Lawrie Wallace called Hanson to say he was too political to return to the museum. With no job and a marital breakup at hand, Hanson phoned his friend Cliff Andstein, BCGEU assistant general secretary. A short time later he was hired by the BCGEU to a job in the union’s Burnaby headquarters. Hanson had been active in the union before taking his LOA from the museum. He had served in various capacities including chairperson of the Victoria local of the scientific component, chair of the province-wide scientific component executive and as a member of the union’s provincial executive.

After two years in Burnaby working as a BCGEU staff representative, Hanson was transferred to the BCGEU’s area office in Victoria. He re-engaged with local politics and was elected president of the Victoria NDP Constituency Association. As the 1979 provincial election approached, Hanson was again nominated with Charles Barber to contest the upcoming general election. He and Barber were successful in the two-member riding, with Hanson finishing three thousand votes ahead of Bawlf. The provincial results, although close, gave the NDP twenty-six seats in the legislature, five fewer than Social Credit, with an almost even split in the provincial popular vote. Hanson remained in the legislature, easily winning re-election in 1983. He and running mate Robin Blencoe beat their Socred challengers by more than seven thousand votes. Hanson’s caucus leadership role in the Thirty-third Parliament of BC gave him a front-row seat to Premier Bennett’s attempt to reshape BC through twenty-four-hour sittings of “legislation by exhaustion.”

The Social Credit budget and spate of legislative bills were stark contrasts to the election outcome on May 5, 1983. Polling during that campaign periodically showed the NDP as a possible winner but on election day, the over 646,000 NDP votes were 2 percent short of the almost 678,000 Social Credit ballots. The NDP candidates in the ’83 election represented an earlier generation of high-profile, solidly social democratic Party stalwarts like Frank Howard, Alex Macdonald, Dave Stupich and a handful of holdovers from Barrett’s 1972 cabinet. And to make life more interesting, Barrett announced he was stepping down as party leader, touching off a leadership campaign.

With the opposition in some leadership turmoil, it is little wonder the Social Credit party sensed an opportunity to drive a new legislative highway through the BC political landscape. The first legislative session of the Thirty-third Parliament following the May 5 election began on June 23, 1983. The traditional pomp and ceremony gave no hint as to what the budget and its accompanying legislation might look like. When the government finally rolled out the budget and the twenty-six bills on July 7 and 8, Hanson remembers that the NDP caucus saw the package as the Social Credit’s final assault on the achievements of Barrett’s 1972–75 government. One former senior political Social Credit staffer says bluntly, “Everything was about the money and economic growth. No thought was given to social policy. The 1983 budget was a chance to get rid of the political opposition.”

Whether the NDP announcement of its intention to filibuster the proposed legislation prompted the government to use twenty-four-hour legislative sittings, or whether the NDP announcement was a simply a reaction to the government’s decision to hold round-the-clock sittings, can be debated at length. The fact is the government would do anything necessary to get its legislative package approved. According to recollections of former cabinet staff, Bennett and his cabinet colleagues “hated the GEU” and had decided on “open warfare” and an all-out assault to win their legislative and public relations battle. Both sides went into full battle mode and civility and common sense were immediate casualties.

Gordon Hanson, MLA for Victoria-Beacon Hill and opposition whip during the 1983 Operation Solidarity legislative debates. BCGEU Archives

Hanson outlines the NDP strategy by saying, “the NDP caucus realized our only strength was to hold the floor. It was decided to divide caucus into two teams each taking a twelve-hour shift in the House to participate in the round-the-clock legislative sessions.” The two shifts were probably a wise course to pursue, as caucus members began to choose their party leadership preferences between popular non-caucus members David Vickers and Bill King. One shift in the legislature was led by Hanson, who was Bill King’s campaign manager. The other shift was headed by MLA and former Barrett cabinet member Colin Gabelmann, who was David Vickers’ campaign manager. Hanson described a “war on the floor” of the legislature. Both parties used every procedural trick in the book to advance their interests. The battle culminated in Barrett being ejected from the legislature, putting more pressure on the opposition caucus leadership team. He was physically dragged out of the legislative chamber by sergeant-at-arms staff and barred from returning for several months.

The opposition efforts were deeply appreciated by labour and community organizations. They needed an effective opposition to buy badly needed organizing time. Although the NDP leadership campaign proved to be a bit of a distraction, the caucus provided superb leadership opposing the government’s agenda. The legislative battle as recorded in the July 1983 edition of Hansard is a priceless window on the public debate between the well-disciplined and professionally led Socreds intent on imposing a fiscally conservative agenda on BC versus class warfare–hardened social democrats intent on defending the social safety net for British Columbians. The parliamentary opposition slowed the government’s progress significantly and allowed unions, citizens’ organizations and community groups to organize a full-blown counterattack on the government. The labour plan was to use coordinated strike action as a central tactic. Since most of the largest bargaining units’ collective agreements did not expire until the fall of 1983, other tactics requiring greater organizing efforts needed to be developed and implemented. From a labour point of view, the battle in the legislature and its accompanying media attention was an important aid to membership mobilization.