Читать книгу Tranquility Lost - Gary Steeves - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter OneBack in Business

ОглавлениеThe proposal in 1983 by the Social Credit provincial government to close Tranquille School in Kamloops, BC, was nothing new. The Social Credit Party and government had adopted the stance that deinstitutionalization was a sound public policy goal. Furthermore, red-headed Socred icon and human resources minister Grace McCarthy had emerged as a leading proponent, primarily because the provincial institutions caring for people with developmental delays were in her ministry.

In the opinion of many observers, the Socreds’ fixation with the goal was based on the cost savings government might realize from the closure of institutions. After a great deal of experience, I came to believe this about the Socreds, too. To them, the consideration of alternate care models for vulnerable British Columbians was secondary to saving money, if it was considered at all. The prospect of reducing the size of government and saving money was just too enticing for Social Credit. Money, not human compassion, was the driving force behind McCarthy and the Social Credit government of Premier Bill Bennett.

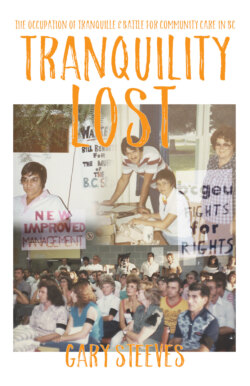

Photo of Tranquille on the cover of BCGEA magazine The Provincial, April 1954. BCGEU Archives

The Tranquille Institution in Kamloops, BC was a supported residence for people with developmental disabilities. It had a long history of providing services in the Kamloops area and was a major part of the regional economy. Prior to providing education and training to persons with intellectual challenges, it served as a tuberculosis sanatorium. Tranquille was located just outside Kamloops on high plains above the Tranquille River. In 1983, it had about 600 full- and part-time staff caring for about 325 residents. The Ministry of Human Resources operated the institution with the intention of educating and training people with developmental disabilities to prepare them for living in the community. Between the end of the 1950s and the early 1980s, 460 developmentally delayed residents had been placed from Tranquille into community-living situations. As residents with mild and moderate developmental disabilities successfully transitioned into the community, Tranquille’s resident population increasingly became people with more profound developmental disabilities. The ministry’s mission and the work of its staff to facilitate community living placement became increasingly more difficult.

The institution was physically huge with forty buildings, its own fire department, powerhouse, industrial laundry, maintenance shops, a canteen, stores and a substantial farm. The farm had 300 acres under irrigation, 150 acres of natural hay meadows, 300 acres of grazing meadows and 13,400 acres of range land. These lands facilitated the raising of 160 head of beef cattle including 50 head of young stock, 75 bulls and 30 steers, 75 Holstein milking cows, 150 breeding cows and 500 hogs. All feeds except grain were grown on the farm. The Tranquille Farm was operated by the provincial Ministry of Agriculture and supported Tranquille’s dietary department, which produced sixty-five thousand meals monthly. It also provided a host of training and educational opportunities for residents.

Regardless of the complexities of the institution and the challenges and successes of the past decades, the late 1970s and early 1980s saw the growth of a movement toward deinstitutionalization. Advocates effectively made the argument that people with special needs deserved community-based care, referring to institutional care as “human warehousing” and “old-fashioned and inhumane.” Their vision of community-based care saw a no less expensive care model. Advocates for community care wanted extensive community-based services and support systems.

The provincial government’s goal to reduce per capita expenditures was not part of the advocates’ agenda. But this fundamental disagreement was set aside, at least temporarily, as the advocates embraced the Social Credit’s deinstitutionalization policy platform. After all, the government had successfully closed the Skeenaview institution in Terrace and Dellview in Vernon. The advocates were comforted by this track record and put aside their differences over funding as government proposed the closure of all institutions for people with developmental disabilities.

BC’s Social Credit Party came into BC electoral politics in the 1949 BC general election. It ran as the BC Social Credit League (BCSCL) and put forth nine candidates. They received only 3,072 votes total for the province and did not elect any members to the legislative assembly.

The 1949 election was dominated by what was known as the Coalition, a group of Liberal and Conservative MLAs including W.A.C. Bennett, the Progressive Conservative MLA for South Okanagan. The Coalition took 61.35 percent of the provincial popular vote and Bennett won his constituency with 58.4 percent of the votes cast. The Official Opposition, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), won 35.1 percent of the provincial vote but only seven seats in the legislature. The pro-business, centre-right coalition had kept the leftist CCF at bay for another electoral term.

The original main building at Tranquille. BCGEU Archives

Despite their 1949 electoral success, the Coalition grew increasingly unpopular over the next three years. As the 1952 general election approached, the Coalition crumbled. Bennett left the Coalition and crossed the floor of the legislature to join the new Social Credit Party (BCSCL). Under a new preferential voting system intended to keep out the CCF, Social Credit went on to win nineteen seats in the 1952 general election. The Official Opposition CCF won eighteen seats and the highest popular vote (34.3 percent) among the parties. The Liberal and Conservative parties won six and four seats respectively and a minority Social Credit government headed by W.A.C. Bennett took office.

The minority Social Credit government did not last the year and British Columbians found themselves back at the polls on June 9, 1953. With the preferential voting system in place again, the final results gave W.A.C. a healthy majority. With less than half the popular vote (45.5 percent), Social Credit won a solid majority of twenty-eight seats in the forty-three-seat legislature. Bennett then brought back first-past-the-post voting and didn’t look back.

Following 1952, W.A.C. Bennett would govern as BC premier for twenty years. W.A.C.’s populist approach on many issues had built a loyal base for his Social Credit Party. The polarized world of BC politics, due mainly to the collapse of the provincial Liberal and Conservative parties, persisted through the 1950s and 1960s. And the steady economic growth of the period suffered only a temporary setback in the late 1950s. Bennett’s government cemented its reputation as a pro-business, socially conservative group by responding to the recession in typical right-wing fashion. It cut spending, eliminated hundreds of public employees’ jobs and slashed welfare payments to the poor.

By 1965, the Bennett government had set a record for the longest continuous government in office by a BC political party. Its 1966 re-election was a walk in the park as Social Credit captured thirty-three of the fifty-five seats in the provincial legislature. The opposition NDP elected sixteen MLAs. Social Credit’s success as a provincial government continued through the 1969 election, when it recorded the highest share of the popular vote in BC history with 46.79 percent. The 1969 election saw the opposition NDP reduced to twelve seats. NDP Leader Tom Berger went down to personal defeat in his riding of Vancouver-Burrard. Few could foresee any slippage in the Social Credit’s grip on power.

Social Credit enjoyed a thriving BC economy fuelled by logging and mining. The coastal forests of Douglas fir, western cedar, balsam fir, hemlock and Sitka spruce provided an abundance of fibre in the mild wet climate, supporting an industry unconcerned with environmental issues. The interior forest industry had lodgepole pine, ponderosa pine and aspen in addition to the coastal species. Accessing markets with timber and mineral products, however, required infrastructure. WAC Bennett did not hesitate to address industry’s needs. His prompt attention to the needs of industry stood in stark contrast to his response to the poor and underprivileged. Bennett saw government’s role as initiating ambitious projects such as road building and power megaprojects. Social safety nets were not a priority for him but he made sure the rail line to northeast BC was completed. He made sure the north and the central interior was connected to the more heavily populated southwest corner of the province. The Kelowna hardware merchant guided BC along the road to economic expansion.

The critique that the CCF/NDP opposition levied at Social Credit was mainly centred on three themes. First, BC resources were being given away for a song. Resource royalty revenue lagged far behind what was being collected by governments in other jurisdictions and this lost revenue meant British Columbians were being ripped off. Second, the NDP said, the BC resource revenue rip-off meant the government did not have the financial ability to address urgent social priorities of the people. Bennett did not regard social programs as important. Health and social service program reforms were ignored by Bennett as he channelled money back into the industries that supported his vision of the provincial economy.

The third criticism was focused on the multitude of societal problems created by an inadequate social safety net in the province. Programs for the vulnerable and assistance for those in need were either minimally funded or non-existent. Bennett appeared oblivious to the needs of the poor or the criticism of his government’s attitude toward them. With an ever-expanding provincial economy, BC’s social safety net trailed far behind other Canadian provinces and developed economies around the world. Even as corporate profits increased, the province made little effort to deal with inadequate hospital facilities, poor mental health services, and incompetent or non-existent care for the elderly.

As successive Bennett governments rolled through the 1960s, the criticism became sharper and more specific. BC needed to be modernized, critics said. A small example was the legislature’s lack of Hansard Services. No record of what the representatives of the people had said or were saying was available to the public. But Hansard, it was argued, costs money and was an intrusion into the unrestricted debate of the legislature. By the 1972 election, BC’s Socreds had governed for twenty years and were being characterized as old and tired. BC’s NDP compared the BC shortcomings with the success of Saskatchewan’s NDP government. In Saskatchewan, handsome resource royalties were collected, automobile insurance was more cheaply offered by a Crown corporation and social programs treated people more adequately. Bennett, they said, was out of touch. Some people in BC noted the irony of Bennett’s criticism of the NDP as socialist hordes who wanted to nationalize private industry. Bennett, in his zeal to open up the interior and the north and supply industry with reliable power as well as provide the province with a stable transportation grid, had nationalized BC Electric to create BC Hydro; nationalized Black Ball Ferries to create the BC Ferry Corp.; and drove BC Rail to the far reaches of the Peace River country. Bennett may have been out of touch with the people, but he was in sync with the industrial leaders who could deliver for him. Just don’t be poor, old, sick or infirm.

Dave Barrett, BC premier 1972–75 and leader of the opposition 1975–84. BCGEU Archives

The unexpected 1972 victory of Dave Barrett and the New Democrats has been well chronicled by Geoff Meggs and Rod Mickleburgh in their excellent book The Art of the Impossible: Dave Barrett and the NDP in Power 1972–1975. Government modernization and enhancement of human services as well as the establishment of public institutions like the Agricultural Land Commission, the Insurance Corporation of BC and the Human Rights Commission remain hallmarks of the Barrett government. The advancement of services to women in particular resulted in the development of rape relief centres, women’s health collectives, daycares and the guaranteed minimum income (Mincome) for those over sixty.

In total, the Barrett government had enacted a total 367 pieces of legislation, about two per week while in office. The 1975 provincial election campaign, however, took BC back in a more familiar direction. In 1972, the NDP had 39.6 percent of the provincial popular vote compared to Social Credit’s 31.2 percent. In 1975, the NDP retained its share of the popular vote, receiving 39.1 percent and received a few more actual votes than they had received in 1972. But Social Credit got 49.3 percent of the popular vote as the Liberal and Conservative vote collapsed.

The NDP election slogan in ’75 was “People Matter More.” New premier-elect Bill Bennett mocked the slogan on election night, saying that “people, not glib slogans, won the election,” but his government was not as interested in people as it was in supporting corporate profitability. Dave Barrett’s “free drugs for seniors” philosophy was quickly vanquished. Bennett immediately assisted the mining and forest industries by dismantling the Mineral Royalties Act and addressing industry concerns about timber royalties. Liberal Leader Gordon Gibson described the demise of his Liberal Party and the arrival of the new Socred government as “a kind of tidal wave of support for the political right.” Social Credit was back in business. By the 1980s, Bill Bennett had “greased every skid” to get industry into the improved profit column. Like his father, Bill Bennett had a love affair with megaprojects. The Coquihalla Highway, BC Place Stadium, the Vancouver Trade and Convention Centre and the Lower Mainland’s Skytrain are all examples of the government’s belief that bigger was better. Just don’t be poor, old or sick. Bennett balanced the government’s generosity to corporations with cuts to government spending on social programs and restraint on public service and teacher salaries.

Bennett’s megaproject spending (such as one billion tax dollars on the development of Northeast Coal) required a broad public sector restraint program. Extensive cutbacks to government services and the outright elimination of some government programs echoed the Social Credit mantra that government was bad and private capital was good. Government employees paid an immediate price for the government’s philosophical beliefs. Government programs, no matter how sparse, were considered generous by Social Credit standards. The health and social service ministries were not spared in the restraint mentality and the provincial institutions they operated continued to struggle from restraints placed on human and capital investment.

In a December 16, 1982 cabinet meeting, ministers reviewed a “Staff Review of Restraint” which cited the 5 percent savings highways had realized due to privatization and the loss of seven hundred employees. It projected further savings as each ministry reduced staff by 250 to 500 employees. But the deputy minister of human resources wrote to cabinet advising of the peculiar circumstances of MHR institutions like Tranquille. The memo said, “A major reduction in the staff in the institutions at this time would jeopardize the overall plan toward decentralized care of people with intellectual challenges. Therefore, the ministry is proposing only a 12 percent cutback at this time.”

All that would change in the near future. Shortly after Bennett’s May 5, 1983 election victory, he convened a cabinet and caucus retreat in the Okanagan to discuss the program his newly re-elected government should present to British Columbians. The featured speaker was a senior advisor to Margaret Thatcher, and the favourite whipping boys for the meeting were public institutions, unions and social programs. Reducing the size and scope of government was the overriding issue. The Fraser Institute provided facilitators for the critical discussions about the future of BC.

The Bennett government, over successive terms, became even more heavily influenced by the Fraser Institute. The Institute was a creation of the leadership of BC’s largest corporations during the term of the 1972–75 NDP government and it ensured that Social Credit had an unending supply of neoliberal research and propaganda material. The conservative economic theories espoused by Milton Friedman were always front of mind as Bennett watched Thatcher and Reagan redefine their countries’ economic and social values. Featuring massive tax cuts to the rich, the crushing of trade unions, deregulation, and privatization of public services, the road map espoused by the Fraser Institute captivated Social Credit. Cabinet ministers had already involved themselves in cabinet-level discussions about the nature of the provincial economy and the service demands on government. A January 26, 1982 cabinet meeting discussed a Garde Gardom memo on “Emerging Issues in Social Services” citing an “aging population, unemployment [and] native persons” as three reasons why social service costs needed to be addressed. By the November 25, 1982 cabinet meeting, ministers were ready to make some decisions based on their deliberations over the previous year. Government wanted economic reform and a reduction of the public service.

On November 25, 1982, cabinet accepted and supported the report on the “Accelerated Program of Government Activity in the Forest, Mining and Transportation Sectors 1982/83.” This program was a major part of the government’s economic recovery and job creation program. It channelled large amounts of money to industry and the formal, legal mechanism to provide taxpayer support to good old free enterprise and its market economy. Apparently, the cabinet believed that government could be a flow-through agency, redirecting tax dollars to private industry without a bureaucratic structure to waste money on.

At the same meeting, ministers approved “Contingency Vote 40, Reallocation of Funds,” which required the redirection of any savings from the Compensation Stabilization Program (CSP) in the public sector “to these economic recovery/job creation measures.” Simultaneously the cabinet shamelessly decided to “reduce government grants by April 1, 1983” by “capping” MHR transfers at 20 percent. The CSP was the government’s chosen method to restrain wages in the broader public sector and Contingency Vote 40 made it impossible to reallocate those funds to public service programs such as community resources for Tranquille residents. Bennett was single-minded in his belief that the private sector’s major employers were to be supported at all cost.

Cabinet documents show that while the government was bailing out company after company (a dam upgrade for Tech Cominco, road maintenance for Granduc Mining, bankruptcy bailout for the Whistler Village Land Co. to name a few), education, health and social service expenditures were being restrained and public service expenditures cut. One January 1983 cabinet document looking at MHR expenditures said, “Other specialized services to be terminated are the post-partum counselling team, the Medical Clinic, in-home services and family and child assessment teams.” It was all about money for Social Credit and they knew exactly what they were doing. Although their specific measures did not always jive with the principles of free enterprise, the government’s public pronouncements tried to suggest otherwise.

The size of government was always a political measure used by Social Credit and they deliberately and vigorously pursued reductions. A February 22, 1983 memo from the assistant deputy minister of intergovernmental relations to the secretary to the cabinet committee on social services explained Treasury Board Order 57 saying, “the policy is established to cover two situations… forced relocation and redundancy.” The memo noted that, “the policy allows alternative work at the present location or termination with severance pay or early retirement where the employee meets the eligibility criteria.” To the cabinet, that was a cost that needed to be brought under control.

The Social Credit caucus discussion took place within the paradigm of an unswerving belief that competition is the defining characteristic of human relations. As British investigative journalist and author George Monbiot has explained, “Democratic choices were best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency.” But the government did not consistently act that way. Perhaps the most controversial tenet of the neoliberal philosophy was that “the Market” was the very best way to organize modern society. That this system would produce winners and losers was only natural because the market would make sure everyone got what they deserved. Did that mean that if you were poor, you deserved to have nothing to eat? Yes! said the pro-market philosophy. The poor were economic losers and Bennett, by his own admission, thought those who disagreed with him were “bad British Columbians.” His government eagerly considered a radical program to make the market the dominant decision-maker in BC.

The changes that would have to be made were to be laid out in the July 1983 budget and its accompanying legislation. The drastic nature of the legislative program and budget came in sharp contrast to the January 27, 1983 presentation to cabinet by the BC Chamber of Commerce. The Chamber expressed its optimism about the economic recovery that had started and made “practical suggestions” to the government about the things they saw as problems. They asked for lower hydro rates, prevention of ferry strikes, property tax relief and money for the tourism industry. The Chamber encouraged the continuation of the government’s involvement in primary industries such as forestry and mining and wanted secondary picketing outlawed. And that was it.

The MLAs, however, talked about advocacy and the need to control “special-interest groups.” According to senior staff of the day, the Bennett cabinet wanted their opposition crushed. Advocacy groups and organizations, big and small, needed to be stifled if Social Credit’s reforms were to be achieved. The Social Credit caucus knew the BC Government Employees’ Union (BCGEU) and other unions would oppose the budget and labour legislation like Bills 2 and 3 and the Employment Standards Act amendments. The caucus agreed that curtailing union power was critical to reducing the size and cost of government. The Social Credit caucus also knew the BCGEU and other labour organizations were the best organized and best funded of all the special interest organizations to oppose the 1983 budget and its accompanying legislation. Bills 2 and 3 would stifle the BCGEU, and Bill 2 would eliminate its power to fight the government. The legislation would give the government the tools it needed to curtail the strength of the BCGEU opposition.

John Shields, first vice-president of the BCGEU, in 1983. BCGEU Archives

On the day the legislation was tabled, still a long way from becoming law, the government began terminating public sector employees. The Socreds fired the two executive vice-presidents of the BCGEU from their provincial government jobs—John Shields and Diane Wood. On July 7, they sent letters to hundreds of employees, the text of which had been approved by cabinet. The letter to the human rights branch employees, signed by acting deputy minister Isabel A. Kelly, said, “This is to advise you that as a result of legislation tabled today, the Human Rights Branch and Commission will be eliminated. As a result of this legislation, and in anticipation of the changes, we are cutting back on staff and your position has become redundant.” Did the government really think British Columbians would just roll over with compliance?

BCGEU flag at Tranquille. BCGEU Archives

The government completely miscalculated the motivating effect the legislation and the termination letters had on BCGEU members. Union membership acted as if they had been pinched in the rear end. Action broke out in most of the BCGEU’s major locals. At times, it all felt like bewildering chaos as union headquarters tried to keep up with developments in various areas of the province. What government misunderstood completely was the ability of the union movement to come together with community organizations large and small, effectively opposing the offensive actions of government. There were thousands of small steps that defined the resistance to the government’s agenda. BCGEU members and community allies worked tirelessly in this regard but in the sunny Okanagan in June, the Social Credit caucus thought they had it all figured out.

Cabinet thought the provincial unemployment rate of about 15 percent (20 percent in Kamloops) called for drastic action. Economic research over the next thirty-plus years would show that neoliberal conservative approaches resulted in significantly lower economic growth rates and an expansion of inequality in both income and wealth. Laissez-faire liberalism had revealed real problems in Europe in the last century but, not surprisingly, the very rich were the real beneficiaries of these right-wing policies.

Social Credit’s long journey from the post-war years to the early eighties was marked by an evolution from a W.A.C.-led populist, pro-business government to a solid right-wing party with neoliberal economic and social policy. By 1983, they were completely wrapped in the cloak of Milton Friedman and Margaret Thatcher, and prepared to see what a majority government could do in BC. In 1983, Bill Bennett was riding high on a newly elected majority government with a well-defined political program and influential right- wing allies in the business and academic worlds. Cabinet records from 1982 through to Bennett’s departure in 1986 show his government providing a steady stream of grants, rebates, forgivable loans and special tax measures for private companies and business organizations.

While ordinary taxpayers subsidized corporate life, the loss of union rights, human rights, tenants’ rights and other advocacy tools would be their reward. Bennett believed a complete transformation was entirely within his grasp, with only the passage of a few pieces of legislation standing between the current recession and economic prosperity. At least that is what Bennett and his caucus said publicly as they proceeded to the legislature on July 7 to tell British Columbians what was good for them. But Tranquille workers did not think much of the budget and its legislative package. The Social Credit philosophy and budget legislation provided the backdrop for a dramatic occupation in Kamloops and unprecedented militancy from Tranquille and other BC workers.