Читать книгу Abomination - Gary Whitta - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

THREE

ОглавлениеTwo horsemen arrived atop a gentle hill and looked down at the open country before them, a sprawling valley of fields and farmland, dotted by a few modest cottages that could barely be called a village.

“This can’t be it,” said the first rider.

“The bloke back at the inn said this was it,” said the other. “Five miles along the only road east, you’ll see it when you get to the hilltop.”

“I know what a knight’s estate looks like. If there were one here, we’d be seeing it, believe me.”

They saw a lone man below, pushing a plow through one of the small farm plots the land was divided into.

“Let’s ask him.”

They rode down the craggy hillside, careful to avoid the rocks and divots. Many parts of England’s rolling countryside were picturesque and pleasant to ride; this was not one of them. One wrong footing on this terrain could mean a broken ankle for a horse and perhaps a broken neck for its rider.

Arriving at the valley floor, they cantered over to the man working the field, a powerful sweat on him as he drove a deep furrow through the earth with the plow. Cast in heavy iron, it looked better suited to be drawn by a horse, but the man pushed it along unaided, as though he knew no better. The two men on horseback exchanged a look of amusement. Farmhands were not renowned for their intellect, but one that did not even know how to work such a basic tool? Wonders never ceased.

The peasant was turned away from the hillside and, consumed by his laborious task, seemed oblivious to the riders who had just arrived behind him, even as one of their horses gave a loud snort.

“Oi! You!”

The plow stopped. The peasant turned and raised his hand, both to shield his eyes from the sun and to wipe away the sweat that soaked his temple. He appeared a particularly uncivilized specimen, his face smeared with dirt, his long hair a stringy, tousled mess.

“What?” he said.

The two riders shared another look, this time not amused but annoyed. Did this peasant not recognize their uniforms? The royal insignia on their tunics?

“‘What?’” the first rider said. “Is that any way for a commoner to address two of the King’s men?”

The peasant took a step forward, out of the glare of the sun. He could see them better now.

“Oh. Right you are.”

The riders waited for some gesture of respect or humility to accompany the peasant’s realization of who they were, but none came. He simply stood there, squinting up at them, as though his original question still stood. Well, what?

Now the second rider spoke. “You do know that plow is meant to be pulled by a horse?”

“Of course. I’m not an idiot,” said the peasant. “The horse is sick. He has a bellyache.”

The first rider was growing impatient. “We are in search of—”

“I should have known those carrots were suspect.”

“Stop talking. Where is Sir Wulfric’s estate?”

The peasant chortled to himself. “I’d hardly call it an estate.”

“So you do know of it?”

The man turned and pointed to the far side of the field he was working. Smoke drifted from the chimney of a modest farmhouse at the edge of the village beyond. Both horsemen looked puzzled, and the first one spurred his horse closer, glowering down from the saddle impatiently.

“We are in no mood for games, friend.”

“What games? That’s his house there.”

Now the second rider spoke again. “That house is far too meager to be the seat of a knight.”

“Well, to be fair, Wulfric also owns this field, and that one there, and that one over there,” said the peasant, pointing. “All rich soil, good crops. Not bad if you ask me.”

“Sir Wulfric, peasant!” the first rider scolded him. “Be mindful how you refer to a Knight of the Realm.”

“And not just any knight,” added the second. “The greatest of all knights.”

“Yes, I’ve heard the stories,” said the peasant, who seemed to be growing tired of this conversation himself. “Greatly exaggerated, for the most part.”

The first rider had finally had enough. He dismounted and marched over to the man, giving him a black look.

“Now look, peasant. I’ve had about enough—”

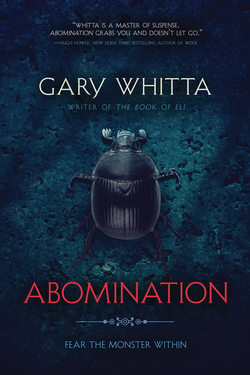

The sun, still setting over the hill, now cast its light upon the silver pendant, wrought in the shape of a scarab beetle, that hung on a loop of leather around the peasant’s neck. It was a simple design, but one familiar to every man and boy sworn to the King’s service. That same medallion had been seen by all who had ever passed through the army barracks at Winchester, in a painting that hung in its main hall. It was depicted hanging around the neck of Sir Wulfric the Wild. Knight of all knights. The man who had saved King Alfred’s life and turned the tide at the Battle of Ethandun, and with it the entire war against the Norse.

The rider’s legs quaked, and for a moment he thought they might give way entirely. Instead he sank to one knee, bowing his head before the dirt-faced peasant. “Sir Wulfric, please accept my most humble apology.”

“Oh, shit,” the second rider exclaimed under his breath. He hurriedly dismounted and knelt at his comrade’s side.

“This field is too muddy for kneeling,” said Wulfric, who despite his station had never grown comfortable at the sight of any man subjugating himself before another. All men were equal in God’s eyes, so why not also in the eyes of men themselves? “Rise.”

And they rose, now regarding this grubby farmworker with the kind of reverent awe normally reserved for gods and kings.

“I apologize,” said Wulfric as he pulled a rag from his pocket and wiped the dirt from his hands. “But the long days in the field can grow dull, and I must find my amusements where I can. Now, what does Alfred want?”

Wulfric left the plow in the field and made his way back to the house as the King’s riders departed the way they had come. It was still early in the day and there was much land left to sow, which now would have to wait. As a rule, he had little time for the commands of kings—but Alfred was more than just a king. He was a friend, and one who had done more for Wulfric than he could ever repay. And so Wulfric, though he detested the thought of picking up a weapon ever again—and that was certainly the only purpose for which Alfred would call upon him—knew he could not refuse.

As a young man Wulfric had been a smith’s apprentice, learning how to forge a sword and make it strong, but not how to wield one. That was for others. The very thought of violence made his stomach roil like a live fish writhing in his belly. Like all Englishmen, he had been raised Christian, but his father had also encouraged Wulfric to think for himself, and so to take from the holy teachings what he would. Of what he knew of the Bible, a single verse had always spoken to Wulfric more than any other: Love thy neighbor as thyself. He wished no man to raise a hand against him, and so he would not against another.

That was until the Norse came.

He was raised in the town of his birth, a small place called Caengiford. London lay just a few miles to the southwest, and it was there, when Wulfric was seventeen, that the Danish marauders had come, smashing the great walls the Romans had built centuries ago, claiming the city for their own, killing anyone who did not have the good sense to flee before them. Wulfric could still remember the displaced and the wounded coming through Caengiford, horribly burned, missing entire limbs, mothers still carrying the bodies of babies that had been trampled or flung against the walls by the barbarians from across the sea.

Wulfric had refused to be shielded from such sights. He wanted to see. Though he did not understand the suffering he witnessed, he knew that turning away from it, trying to pretend it was not real, was somehow irresponsible. And he knew that these horrors could as easily be visited upon him and his. He just did not realize how soon.

The Norse arrived in Caengiford the next week. A raiding party sent to hunt down those fleeing the city found Wulfric’s village instead, and since their nature was to destroy all before them, they set about burning it to the ground. Wulfric barely made it out alive, slipping through an open window at his mother’s insistence while the Danish brutes outside hammered at the door. He escaped a moment before they burst through, and he ran into the forest as fast as he could, never looking back. Thus he did not see his mother’s and father’s fate, nor that of his four younger brothers, too little to run. But his imagination served well enough, and even years later, he could not bring himself to think of it but for when old memories came unbidden, in nightmares.

After escaping the destruction of his village, Wulfric stole a ride on a merchant’s cart until he was discovered and thrown off. After that he walked. He had no destination in mind, nowhere to go. Wherever the Norse were not, that was good enough for him. He lost count of the weeks he traveled alone, sleeping by the side of the road, eating whatever he could find in the woods or, on a good day, whatever might fall—or be encouraged to fall—from a passing cart. One day he asked a passerby where he was and discovered that he had wandered as far as Wiltshire. He made his way to a small town and, after demonstrating his ability with hammer and tong, was taken on by the local smith. There he earned his keep making farming tools and shoes for horses, and as time went on, ever-increasing numbers of swords. Alfred’s war against the Norse was not faring well, it was said, and weapons were needed to arm the men being pressed into service from every county.

It was a smith’s job to check the weight and balance of every sword as it cooled from the forge, but Wulfric always found an excuse to leave that task to the other apprentices. Even holding a sword felt wrong to him; the thought of running a man through with one made him queasy. He tried to tell that to the King’s recruiters, when they rode into town to muster every able-bodied man they could find, but all he got was a firm clip round the ear and orders to report to the barracks at Chippenham by week’s end or be marked a deserter.

Wulfric weighed his options and thought briefly of running. But he knew of the army’s relentless pursuit of cowards who defied the King’s commission, and he did not relish living another long while on the run, much less the punishment were he to be caught. And so he arrived at Chippenham on the very last day before he would have been declared an absconder. There he was given livery and a wooden sword to practice with and thrown immediately into mock combat. In a time of peace, his training might have followed a more unhurried pace, but the Norse were advancing on every front, and there was little time to do else but throw new recruits into the thick of it and hope that they could fight, or learn to in short order.

Even a mock sword felt ugly in Wulfric’s hand, yet he found that although he had no wish to fight, he undoubtedly had a knack for it. More than a knack—an instinct. On his first day sparring in the training yard, he went right at the master-at-arms, a bearded, barrel-chested soldier with more years of combat experience than Wulfric had on this earth. Armed with only a blunted blade of wood, he fought with such speed and ferocity that the instructor wound up on his backside, stunned. The other trainees applauded and hollered, but Wulfric was more surprised than anyone; it was as though some other entity had taken possession of his sword arm, of his entire body, driving him forward. In those few seconds, he had become someone else entirely, someone ugly and brutal and merciless. In other words, exactly the kind of person his superiors were looking for. It was noted that while there was little artistry in the way Wulfric fought, there was a savage purity to it. He fought more like a Norse than an Englishman—a fact that would, in time, chill the blood of both alike. The Norse had a name for men like Wulfric, men who fought and killed without fear or mercy or grace. Berserker.

The nickname stuck fast. Throughout the Chippenham ranks he became known as Wulfric the Wild. Wulfric hated the name, but not the respect that accompanied it. Nobody cuffed him on the ear anymore. Instead, from then on, Wulfric was watched closely by his trainers, marked as one of a few who had something special, something that could be used to great advantage out on the field. When it came to battle, as it inevitably would, he and others like him would be placed close to the King to afford him the greatest protection.

Battle came sooner than expected, in the deep cold of mid-winter and on Twelfth Night, no less. Wulfric and the other trainees had been enjoying the last of their Christmas rations on the night the Norse stormed the walls of Chippenham.

Alarm bells sounded, rousing sleepers from their beds as, outside, barbarians poured over the walls and battered down the gates of the English fortress. Officers rushed to the barrack rooms to mobilize as many men as they could. There, a sergeant who knew Wulfric grabbed him by the collar and sent him in the other direction from his young comrades. He went where he was bid and found himself outside the royal chamber itself, where Alfred’s personal guard and a troop of other heavily armed men were moving the King to safety.

It was the first time Wulfric had seen Alfred, though he thought he might have spied the King once before, looking down on the training yard from the parapets. But there was no mistaking this time: Wulfric was just a few feet away from the King as the man was bundled from his room half-dressed, having just moments before been roused from his royal bed.

“Wulfric, come here, lad!”

Wulfric’s master-at-arms, the man he had charged and put on his back that first day in the yard, was beckoning urgently. When Wulfric approached, he felt the leather bindings of a sword hilt pressed into his hand. It felt so much heavier than the wooden dummies he had been practicing with. He looked down and saw the metal blade glimmer in the torchlight. The first true sword he had ever held as a soldier.

“Stay with the King! Stay with the King!” the master-at-arms bellowed, and he pushed Wulfric along with the rest of Alfred’s company as they rushed the King along the hallway. It was all happening so fast. Outside could be heard the sounds of battle—the clash of metal on metal, the roaring of fires, the screams of wounded and dying men. Sounds Wulfric had not heard since fleeing his village two years before.

It was outside that Wulfric killed his first man. He brought up the rear of Alfred’s protective huddle as they exited the hallway into the chill air of the courtyard. Wulfric’s first thought was how bitterly cold it was and how he wished he’d had time to grab his warmer tunic before he’d been herded out of his room. Then he heard a war cry that curdled his blood and turned to see a giant Norseman charging at him, face hidden behind a long braided beard and a battered metal helm. The warrior was easily twice Wulfric’s size, and looked to him more like an ox that had learned to walk on its hind legs. But that was all the observation he had time for before the Dane was upon him, swinging an oversized hammer that was unlike any weapon of war Wulfric had ever seen—and he had forged many.

Wulfric jumped backward to avoid the first blow, but the Norseman was quicker than his size suggested, and his second attack came too fast for Wulfric to anticipate. This time he managed only half a dodge before the maul struck him in the shoulder and knocked him to the ground. He looked up, dazed, to see the great bull of a man bearing down on him, hammer overhead in preparation for the killing blow.

But Wulfric had not lost hold of his sword. He swung low, slashing the Norseman deep across the ankle. The Dane cried out and went down on one knee, dropping the hammer. He drew a knife from his belt, but now it was Wulfric who surprised with his speed. He leapt back to his feet and swung his sword upward like a farmer chopping wheat with a scythe. It caught the Dane on the underside of the neck and buried itself deep in his throat.

As the giant’s blood sprayed out onto the cobblestones, time seemed to slow, and Wulfric noted that it was curious how blood appeared black, not red, in the pale light of the moon. And then time resumed its normal rate again, and Wulfric drew back his sword. The motion pulled the blade free from the Dane’s neck and brought him crashing to the ground. Wulfric stepped back to avoid the dead man’s blood staining his boots as it pooled out toward him, then ran to catch up with King Alfred and his men.

The ox was the first man Wulfric killed in battle, but far from the last. Many more were to come in the months ahead. Alfred and his company, along with the rest of those who managed to escape the disaster at Chippenham, retreated south to the Isle of Athelney in neighboring Somerset. The small island provided a bottleneck that protected them from the type of frontal assault suffered at Chippenham and afforded Alfred time to regroup.

Not that he had much left to regroup; most of his men had been killed or captured, and the small force that remained could scarcely defend itself, let alone stage a counterattack. But Alfred refused to be cowed, even after a crushing defeat and with so few resources at hand. He sent word to every nearby village and town, commanding men to rally to his banner. And rally they did. After several long months of rebuilding his army, Alfred took it back onto the field and met the full might of the Danish host at Ethandun.

It was to be a bloody morning, not least for young Wulfric, who, since first drawing blood in the battle against the ox, had discovered that he now had not only a talent for killing, but a taste for it. After the fall of Chippenham, the Norse had hounded Alfred’s retreating army halfway across Wiltshire before finally breaking off pursuit. Along the way, there had been several bloody skirmishes, in which Wulfric had claimed many more Danish heads. In each battle, it was as though some inner savage that usually lay dormant within him awoke and asserted control until the fight was over. After the killing was done, Wulfric could feel nothing but remorse for the lives he had taken. But when he was in the thick of it, bloody sword in hand, it was as though he had been born to do this and nothing else. None who fought alongside him, who witnessed this transformation, could disagree. And over time, Wulfric’s nickname, given in jest after that first day in the training yard, began to strike his comrades-in-arms as wholly inadequate.

But on that day at Ethandun they saw something else entirely. Wulfric had already killed at least twenty Norsemen in the battle—the royal crest on his tabard had entirely disappeared behind a thick coating of Danish blood—when he wheeled around to realize King Alfred was nowhere to be seen. Lost in the reverie of slaughter, he had broken the one rule his master-at-arms had given him: Stay with the King! He searched the melee, cutting down any Dane unfortunate enough to stray within striking distance, until he caught sight of the King on his horse. And even from fifty feet away, Wulfric could see that Alfred was in trouble. The Norse were swarming his position, cutting down his personal guard, making their way closer to the man Wulfric had taken an oath to protect.

Wulfric surged forward and reached the King just as a powerful Dane dressed in furs and mail reached up and pulled Alfred down off his mount. With the King defenseless on the ground, the Norseman drew back his axe for the killing blow. That was when Wulfric charged into the fray, piercing the Dane’s mail armor with his sword. The barbarian slid off Wulfric’s blade, dead, even as three more moved in to finish the job he had started. Wulfric, breathing hard, took up a defensive position between the Norsemen and his King.

The first man to attack went down quickly: Wulfric dodged the Norseman’s swinging sword and slashed him across the back with his own. The second and third came at Wulfric together, thinking to better their odds. It did, but not nearly enough. Wulfric ran his sword through the open mouth of one, but when the blade became stuck in the back of the man’s skull and could not be pulled free, he let it go, and took on the other man unarmed.

This one carried a crudely formed cudgel, little more than a heavy hunk of wood with iron spikes hammered through it, but deadly enough, especially at arm’s length. Wulfric, driven by the war spirit that possessed him in battle, knew that his best chance was to get in close. He waited for the Danish brute to take a big, lumbering swing, ducked under it, then charged at the man, tackling him to the ground. The Norseman was still by far the stronger and would doubtless prevail in a hand-to-hand grapple, but Wulfric would not let it come to that. He drew a stiletto from his boot and drove it into the barbarian’s right eye, deep enough to skewer his head to the ground beneath.

Wulfric fell back onto the ground, exhausted. More English soldiers now rallied to the King’s side, surrounding him. Two men helped Alfred to his feet. None did so for Wulfric. They had not witnessed the encounter; to them he was just another common infantryman, not worthy of their concern. But one man had noticed: Alfred. As he was escorted to safety, his eyes never left Wulfric, the young man who had just saved his life.

Alfred went on to a great victory at Ethandun, and the war turned after that. Alfred routed the Danish host and pursued the surviving rabble all the way back to Chippenham, where the rest of the Norse were by now garrisoned. With the Danish king, Guthrum, sequestered inside, Alfred saw his chance to break them once and for all. Thus, with his entire force arrayed around Chippenham’s walls, Alfred began a slow siege. After two weeks, the Norse within were starving, their will to resist broken. In desperation, Guthrum sued for peace, and Alfred offered the terms that would at last bring the war to an end.

After his triumphant return home, Alfred’s first order of business was to have the young infantryman who had saved his life at Ethandun brought before him. Wulfric had no idea why he had been summoned to the royal court, and so was surprised when he was told to kneel and felt the flat of Alfred’s sword touch first one shoulder, then the other. “Arise, Sir Wulfric,” the King said. And the young man who once swore he would never so much as hold a sword rose, a knight.

Wulfric was a common man with no noble heritage, and so it was explained to him that all knights must have a coat of arms to signify their house. With little heraldic precedent to draw on, Wulfric decided to take as the symbol of his house a cherished memory from his childhood. His father had taught him as a boy to identify all manner of curious beetles and bugs, and Wulfric’s favorite among all was the scarab beetle. His father had explained that its armored shell made it hardy and resistant to all manner of hostile conditions. Wulfric, who knew the hard life of a peasant, had liked that. He also liked that the scarab’s favorite pastime was to collect dung. And so it was that years later, wrestling with the fact that he was no longer a commoner but a Knight of the Realm, he thought it the perfect way to remind himself of his lowly beginnings. For what could be more lowly than an insect that spends its days half-buried in shit?

Once Wulfric had a coat of arms by which his house could be known, all he needed was a house. Alfred granted him his choice of castles and lands up and down the kingdom, but Wulfric would take none of them. Instead he settled on a house and a plot of land where he could raise turnips and carrots and perhaps find a wife for himself. If God were willing, perhaps he would even see fit to bless him with a son or daughter, but Wulfric would not ask for anything he had not yet earned. To his mind, all he had done of note was kill men in battle, and he did not see why that should ever be rewarded.

When Wulfric stepped through the door, Cwen, his wife, turned in surprise from the stove where soup was cooking. “You’re back early,” she said. “Did you forget something?”

By God, that soup smells good, Wulfric thought as the aroma hit him. Of all the reasons he had chosen Cwen for his wife, her cooking ranked only second. Well, perhaps third, he thought to himself.

“Yes,” said Wulfric wearily. “I forgot, if only briefly, that I will never be out of Alfred’s debt.”

Cwen did not appear to like the sound of that at all. She placed her hands on her hips and frowned at him. “Please, not that look,” Wulfric said as he sat. “How about some of that soup?”

“It’s not ready yet,” said Cwen, softening not even a little. “What do you mean? Those riders I saw on the hill, they were the King’s men?”

“He’s summoned me to Winchester.”

“And of course you said no.”

“I could hardly do that. Not after everything he has done for me. I must at least go and see what he wants.”

Cwen stepped out from behind the kitchen table. She was getting bigger every day. The child was due in only a few months. That was why Wulfric was out on the plow, though the horse was sick. When his son was born—somehow, Wulfric knew it was to be a boy—he would not want for food to eat, nor any of the things that Wulfric had gone without as a child. He would be the son of a knight. Perhaps Wulfric would ask Alfred for that castle after all, so that his son might grow up in it.

“You’ve got it backward,” Cwen said sternly. “You’ve always had it backward. It’s Alfred who owes you, not the other way around. He’d be dead if not for you.”

“I only did what I was sworn to do,” said Wulfric. “What any soldier would have done in my position. But Alfred did not have to knight me, nor set me up for life the way he did. Look at all that I have—more than I ever dreamed. My own house, my own land.” He rose from the table and took his wife by the hand. “My own wife, the most beautiful in the world.”

“Save your flattery,” said Cwen, though the faintest hint of a smile suggested that it had made its mark. “I am quite sure Alfred did not grant me to you.”

“True, but I would not have won you had he not made me a knight.”

“I didn’t know you were a knight when I agreed to marry you.”

“If I were not, I would never have had the courage to ask,” he said, close enough now to kiss her. And kiss her he did.

They kissed, and made love, and later Wulfric got his soup, and they ate together by the hearth.

“Don’t think,” Cwen said, looking up from her bowl, “that with a few fine words and a quick roll on the bed you can buy me off. You’re not disappearing off on some campaign. I want you here when the baby is born. I need you here.”

“Who said anything about a campaign?” Wulfric replied.

“Do you take me for a fool? Why else would Alfred send for you? I’ve heard the rumors about the king in the Danelaw. They say he’s nearly dead and that the Norse may rise up again under some new warlord.”

“Rumors, that’s all,” said Wulfric. But Cwen knew him well enough to know that while he might wish that were true, he did not believe it. She reached over and took her husband’s hand.

“Wulfric, look at me. I know Alfred is your friend, but I am your wife, and this is your child.” She placed her other hand over her bulging belly. “I want you to promise me, here and now, that you will not let him send you on some new war against the Norse.”

Wulfric squeezed her hand tightly, met her eyes. “I promise.”

Satisfied, Cwen smiled and returned to her soup.

“I’m sure it’s nothing, really,” he said. “Maybe Alfred burned another batch of cakes and wants to borrow you for his new head cook.”

Cwen laughed, and kissed him on the forehead, and rose to fetch them both another bowl.

Early the next morning, Wulfric left his house with a saddle and provisions for a long day’s ride over his shoulder. He unbolted the door to the stable, and his horse, Dolly, peeked out from the gloom inside.

“How are you today, old girl?” he asked. Dolly did not reply until Wulfric brought the saddle down off his shoulder and slung it over her back. She stamped a hoof and snorted unhappily.

“Oh, stop complaining,” said Wulfric as he fed her a handful of oats. “You had all of yesterday off. Today, bellyache or not, we ride. We’re going to see the King. And I’ll bet you his carrots are a lot better than ours.”