Читать книгу Abomination - Gary Whitta - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

FOUR

ОглавлениеWulfric arrived at Winchester early that evening. He had ridden tirelessly throughout the day, eating his lunch in the saddle, stopping only so that Dolly could briefly rest and drink and get her oats. Wulfric hated the thought of being away from Cwen and the little one for even one night, and he would do whatever was in his power to avoid a second. Perhaps, he thought, Alfred wanted only a small thing, and in making such good time he could be back home with his family tomorrow.

Perhaps. The King was not wont to send riders to summon his most trusted knight over a trifle, but still Wulfric had entertained himself on the journey by imagining all the reasons Alfred might want to see him that would allow him to be home before the next sunset. By the time Alfred’s castle appeared on the horizon, Wulfric had been forced to accept the gloomy truth that those reasons he could think of could be reckoned on one hand. And none of them seemed likely.

The guardsmen on watch atop the castle battlements had spied Wulfric coming along the road from some distance away, and the great fortress’s gates rumbled open as he approached. Dolly’s hooves clopped across the drawbridge, and as Wulfric passed beneath the barbican into the outer yard, he was reminded why, as much as he loved Alfred, he rarely enjoyed visiting his friend’s royal seat. The guards and other men-at-arms who met him as he entered gazed at him in quiet fascination, as though some mythological hero made flesh stood before them.

To many of these young men, of course, that was exactly who Wulfric was. Sir Wulfric the Wild. The man who had killed more Norsemen than any other in the Danish campaigns, by more than double. The man who had single-handedly slaughtered a dozen barbarians in defense of the King’s life and then refused the lavish lands and riches offered him in reward. The man who, it was said, the King trusted and listened to above all others, even the Queen herself.

Wulfric tried to avoid the eyes of the man who took Dolly’s reins for him as he dismounted, but he could feel them boring into him. This would be the story of his visit here, he knew. An unremitting parade of genuflection and reverence that would soon have Wulfric itching for home, where the merest suggestion of any such display would earn him a hard rap on the knuckles with a wooden ladle. He liked that far better than this.

He hoped at least to avoid visiting the barrack where that god-awful painting of him hung. Wulfric had refused to sit for it, and so the artist had been forced to make do with whatever descriptions and drawings he could garner from others. The result, Wulfric had thought when he first saw it, was ridiculous. He was depicted holding a shining sword aloft in an absurdly heroic pose, all puffed up with pride, a trait that Wulfric had taken pains to avoid his entire life. The artist had even restored the part of his ear famously lost to a Danish axe at Ethandun, as if it were better that he appear invulnerable. But Wulfric liked his ear the way it was. It served as an ever-present reminder to himself that death was never more than an inch away, that even the most celebrated warriors were as mortal as any other.

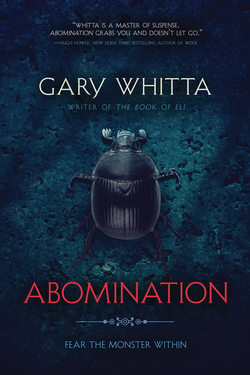

It might have been useful to the young soldiers who passed through here to be reminded of that also; as it was, the painting would inspire in those men only a naively romanticized notion of heroism, one that would be roughly dispelled in their first real battle. The only thing rendered with any accuracy at all, Wulfric thought, was the scarab pendant that hung around his neck—they had, at least, got that right. Yes, definitely avoid the barracks, he reminded himself. Then he thanked the man who stabled his horse and made his way across the yard toward the inner bailey and the castle’s central keep, where Alfred resided.

Just being here in the royal household, with all its trappings, made Wulfric uneasy. The idea of royalty had always struck him as inequitable, an attitude no doubt inherited from his father. No man is greater than another by birth, he had taught his young son. Only by deed. But Wulfric was also a man of God, and kings and queens, many believed, were chosen by God himself, for he alone knew who among the people had it within themselves to lead their country to its rightful destiny.

Having witnessed firsthand what Alfred had accomplished, Wulfric found that belief difficult to argue against. The crown had been thrust upon Alfred at a young age, after the untimely death of his brother, and he had, through sheer courage and audacity, turned years of bitter and bloody defeat at the hands of the Norse into the unlikeliest of victories. He had brought England back from the brink of annihilation. Now, thanks to his guidance, it was safer and stronger than ever. Could any other man have done such a thing? Could Wulfric? He doubted it.

Though Wulfric knew as well as anyone not to use the name Alfred the Great in the King’s presence, he believed it to be warranted. For he was a great King and, more than that, a great friend. He had not needed to reward Wulfric for doing a soldier’s duty, but everything Wulfric now counted as a blessing in his life he owed to his friend’s generosity. The two of them had spent countless hours together, eating and telling stories and slowly coming to the mutual realization that in another lifetime they would have been brothers. As it was, in this one, they practically were.

“Wulfric!”

Alfred strode briskly across the Great Hall and clapped his arms around Wulfric in a fond embrace. And in that moment, with all royal formality dashed away by that informal gesture, Wulfric’s unease lifted. They were surrounded by enough timber and stone in this one room to build Wulfric’s house twenty times over, yet Alfred’s greeting made him feel as though he had simply wandered over to visit his neighbor, Brom, to borrow a loaf of bread. He was in the company of a friend first, his King a distant second. He returned the embrace warmly.

As they separated, Wulfric could see that all was not right. Alfred looked tired and haggard, as though he had not seen a good night’s sleep in some time. Whatever predicament had led him to summon Wulfric was no doubt the cause, and Wulfric wanted nothing more than to know the nature of it, but it was not his place to ask.

“My thanks to you for coming so quickly,” said Alfred, as cheerily as he was able. “How was your journey?”

“Uneventful,” Wulfric replied. “I made good speed, which I hope to also on my return.” He wasted no time letting Alfred know how keen he was to be on his way.

Alfred laughed. “You’ve only just arrived and already you’re planning your trip back?”

“Your invitation is never anything less than an honor,” said Wulfric. “But I am reluctant to be far removed from Cwen at the moment.”

“Ah, how is the beautiful Cwen? Wait, she’s not sick, is she?”

Wulfric beamed in the way only an expectant father can. “Far from it.”

Alfred knew that look. He had six children of his own. A grin spread across his own face, and he grabbed Wulfric by the shoulders and embraced him again, more firmly. “God bless you, you horny bastard!” he exclaimed with a laugh. “How far along?”

“Six months, thereabouts. Her back aches and she waddles like a duck, and last week I swear I saw her eat a piece of coal. But for all that, she is still the most beautiful woman I could ever hope to lay eyes on, much less have married.”

“She is that,” Alfred agreed. “Do you hope for a son or daughter?”

“Cwen gives no mind to that and prays only that it has its health. As do I, although whenever I dream about it, it is always a boy.”

“I have no doubt of it,” Alfred said, the smile fading from his lips. “I pray that we might have you home before he is born.”

And something inside Wulfric sank like a stone.

They ate dinner together that night in Alfred’s private chamber. Wulfric had no appetite. He had suspected, of course, that his hope of returning home the next day was a fantasy, but now it was confirmed. Whatever task lay before him was to be measured not in days or even weeks, but in months.

Alfred seemed determined to put off discussing anything of import for as long as possible, leaving Wulfric to nod and smile politely as he privately tortured himself with questions of what lay in store for him. He cringed as he remembered the promise he had made to Cwen just before he left. What are your words worth, he asked himself, if they crumble into dust so easily? But to whom did his allegiance belong? His beloved wife carrying his unborn child? Or to his best friend and his King, to whom he owed everything he had? He found himself praying for some hope of returning home without having broken his covenant with either.

“Do you believe in witchcraft, Wulfric?”

Wulfric’s attention returned suddenly to the table. The King had been talking for some time, but the oddity of the question was such that it stood out from all the rest.

He waited for Alfred’s face to crack. The King never had been able to keep a straight face when telling a joke, but Alfred’s expression now was as somber as Wulfric had ever seen it, even during the darkest days of the war. This was not a jest. And there was something unsettling about the look in Alfred’s eyes. It suggested that he knew more, much more, about the subject he had just broached than he had yet volunteered.

Wulfric thought carefully about his answer before speaking. “I’ve never seen any evidence of it.”

“You’ve seen no evidence of God, either,” Alfred replied, as though anticipating the answer. “And yet you believe.”

“God was with us at Ethandun,” said Wulfric. “We could not have turned the tide of battle otherwise. I remember you said so yourself.”

“Direct evidence,” the King retorted. “Something before your very eyes that defies all nature, and science, and reason. Something that cannot be explained.”

“Then no. But faith is the evidence of things not seen, is it not?”

For a long moment, Alfred did not speak. He simply fingered the stem of his goblet and stared into the blood-red surface of the wine within, lost in some dark thought.

“I have seen things,” he said at last, his voice not much above a whisper. “Things that have led me to question my own faith. And may cause you to question yours.”

A gust of wind howled against the window. Wulfric could not tell if the room had suddenly grown colder or if it was his imagination. Either way, Alfred’s demeanor troubled him. These were not the words of a rational man, and Wulfric had never known his King to be anything but.

“Why am I here?” he asked, finally.

“In the morning, I will show you,” said Alfred as he rose from his chair, prompting Wulfric to do the same.

“I am not tired,” said Wulfric, determined to get to the source of whatever was causing this uncharacteristic behavior. “I came a long way. If this is why I am here, if you have something to show me, show me now.”

“In the morning,” said Alfred. “The things I speak of should not be seen so late before sleep.”

Wulfric did not sleep. Instead, he tossed and turned restlessly through the night, partly because the bed, though far more comfortable and spacious than his own, was not his own. He had rarely spent a night away from home since making his new life there, and when he did, sleep did not come easily. He missed the feel of his own pillow, lumpy as it was. He missed the smell of whatever Cwen had been baking, left out to cool overnight. And most of all, he missed Cwen, the warmth of her back as he nestled himself against her, his hand on her firm, round belly, feeling the gentle stirring of his unborn child within. All the luxuries and appointments of Alfred’s castle only reminded him how far he was from them.

But mostly he did not sleep out of concern for his friend. He had seen Alfred drawn and wan before—many times while on campaign—but never like this. Wulfric knew better than most the strength of the man, knew that it would take the gravest of matters, more grave even than war, to weigh so heavily upon him. Alfred’s words repeated incessantly in Wulfric’s head as he shifted uncomfortably beneath the bedsheets. I have seen things that have led me to question my own faith. Wulfric knew that Alfred’s faith in God went to the very core of his being. It made him the man he was, had given him the strength to drive back the Norse even when all seemed lost. If all the horrors of battle, of seeing comrades bloodied and cleaved all around him, could not shake this man’s belief, then what in God’s name could? It was a question Wulfric could not solve, though he racked his brain, and it haunted him still when the first cock crowed and one of Alfred’s pages arrived to fetch him.

Alfred was waiting for Wulfric in the Great Hall. He made no offer of breakfast, nor did he enquire how Wulfric had slept; it was plain enough to see. While the King last night had seemed determined to delay the matter at hand, this morning he was equally determined not to tarry. He escorted Wulfric from the hall and through the castle’s winding hallways until they arrived at a door with which Wulfric was not familiar; he thought he had seen all of the castle in his time here, but this was new to him.

The door was constructed of the heaviest oak and barred by an iron gate that appeared to have been added recently. Two guards stood watch by the entrance. Wulfric did not like it here. He had never much cared for small spaces. Looking back now, he realized that the walls and ceiling had been gradually contracting as they progressed along the hallway, so that now they stood at the end of what felt more like a tunnel. He was already beginning to feel distinctly uneasy.

“What is this?” he asked.

“The dungeon,” Alfred replied. He nodded to one of the guards, who unlocked the iron gate and swung it open, then did the same with the door behind it.

“Here,” said Alfred. He produced an embroidered cloth and offered it to Wulfric. It was damp, and there was an almost overpowering, but not unpleasant, odor from whatever the material had been soaked in. Wulfric was no herbalist, but his friend Aedan, who owned the field neighboring his, grew many types of fragrant plants, and so he recognized the smell—a concoction of lavender and mint. It was not unlike the perfume Cwen had made for herself from the bushel of herbs Aedan brought them as a welcoming gift when they first set up house, and for a moment Wulfric found it comforting; it smelled to him of home.

Then the dungeon door opened with a creak and something else rose up out of the dank, musty air within. Wulfric could not identify it—he had never before smelled anything quite like it—but it was foul. He immediately pressed the cloth against his nose and mouth, but even the strong aroma of the perfume only partially blocked out the stench. Wulfric looked at Alfred and noticed that he had no such cloth of his own. “Where is yours?” he enquired.

“It pains me to say that I have grown accustomed to the smell,” Alfred replied. He lifted a flaming torch from its cradle on the nearby wall and they began their descent.

Wulfric followed the King down the winding stairs, the two of them led by one of Alfred’s guards while the other remained above, locking and barring the door behind them. All trod warily as they descended, Wulfric most of all; the dank stone steps felt slippery underfoot, and his mind was racing with thoughts of what might await them at the bottom. Winchester’s dungeon was reserved not for deserters or common criminals, who typically languished in the stockade, and not for high-ranking enemies of the crown, who were sent to the tower, but for the worst and most despicable of those who sought to harm Alfred’s kingdom. Who was down here? A captured Danish spy with tidings of a fresh plot? A foiled assassin? Or something beyond even his busy imagination? Wulfric did not know whether to feel relief or dread in the knowledge that he would find out soon enough.

With each step, the fetor wafting from the darkness below grew more powerful. Wulfric twisted the cloth Alfred had given him to wring out more of its perfumed scent, but it was no use. Even with the cloth pressed firmly against his face, the stink was so strong by the time they reached the bottom of the steps that Wulfric could barely keep himself from retching. What the hell was it? Sulfur, perhaps? Similar, but worse.

Even in the bright light of their torches, the narrow corridor at which they arrived gave up little. The stone walls on either side extended for only a few feet before disappearing into the deepest, most impenetrable blackness Wulfric had ever seen. This was no ordinary darkness, not simply the absence of light; it was as though something down here was radiating darkness, filling every corner of this dungeon with it. Wulfric was not a man easily unnerved, but at this moment he was gripped by a powerful desire to retreat up the steps, to be away from this place. Still, he stood firm.

The guard, his torch lighting the way, led Alfred and Wulfric down the narrow corridor, passing cell after empty cell. Though the flame burned brightly, it stubbornly refused to reveal anything more than a few feet ahead. It should have cast at least a dim light down the tunnel’s entire length. Here, it shrank to an isolated sliver of light in a sea of unyielding black.

Wulfric began to hear something. A scratching sound in the dark up ahead. Snorting and snarling. Some kind of animal. It sounded to him sickly, or wounded, but not in any way that he had ever heard, and he had tended many an animal on his farm. He shivered as his suspicion grew that whatever was being held down here fell into that last dreaded category—the thing beyond his imagining.

The guard came to a halt. “Go no farther,” he warned. Before them a line had been daubed across the floor in woad, and a few feet beyond, the iron bars of the final cell at the hallway’s end could be dimly seen in the flickering dark. This cell looked different from the others. The lower half of the bars were ridden with rust and a strange, greenish corrosion; they were pitted and scarred as though something had been chewing at them, and some were still dripping with a wet, viscous saliva.

Something behind those bars was moving, something primal and ugly, scratching and snorting around the floor of the cell. Whatever it was, it lived low to the ground. But Wulfric caught only brief, partial glimpses of it in the dim light. For a moment, he thought he could discern a clawed foot, like that of an oversized cat. But then the torchlight reflected a glimmer of reptilian scale. Was his mind playing tricks with him, down here in the darkness?

The guard used his torch to light another that hung from the wall. He waited for its flame to bloom fully and then tossed it low against the foot of the iron bars. Wulfric jolted back in alarm as the creature within let out a shriek, amplified by the close stone walls, that set the hairs along his arms and neck on end. The creature retreated from the flames, into a dark corner of its cell, but then it slowly came forward again, into the light, and Wulfric at last saw the full nature of it.

It moved across the rotten straw lining the cell floor on six squat, lizard-like legs, each webbed foot bearing several large, horned claws. Its body was scaled but shaped like a potbellied hog, and it had the snout and tusks of one, too, although its lidless eyes were distinctly reptilian, bright red with slitted yellow irises. The unnameable thing approached the fallen torch, sniffing at the burning embers through the bars. And then the thing reached through and snatched the torch with its mouth, wrestling with it for a moment as it tried to pull it through the bars. Finally it dropped the torch, then grabbed it again by its tapered end, pulling it through the bars longwise. Wulfric watched in morbid fascination as the beast opened its jaws wide, revealing rows of slavering, needle-like fangs, bit down on the torch with a loud crunch, then shredded it to splinters in a frenzy before swallowing it down, flames and all.

The guardsman took a step back, ushering Alfred and Wulfric with a raised arm as he did so. A moment later, after swallowing the last of the torch, the beast belched out a hot burst of bright orange flame. In the brief eruption of light, Wulfric saw that much of the cell’s walls had been charred black by fire.

Against his better judgment, Wulfric found himself moving closer, unthinkingly stepping across the line on the floor. Alarmed, the guard reached out and grabbed him by the shoulder, but it was too late. The beast caught sight of Wulfric and went wild. Slavering like a rabid dog, it threw itself hard against the bars, screeching as it clawed at the air. As the guard tried to pull Wulfric back, an impossibly long tongue uncoiled from the creature’s mouth and snapped around Wulfric’s wrist. He cried out and tried to pull free, but the beast was stronger. It scuttled backward, toward the rear of the cell, dragging Wulfric with it.

Alfred grabbed Wulfric’s free arm and dug in his heels. But even their combined strength was not enough. As the two of them were dragged closer to the beast, the guard drew his sword and began hacking frantically at its tongue, severing it only on the third strike. Finally free, Wulfric and Alfred fell backward onto the floor. The wounded beast rolled onto its back as well, howling and kicking its feet hysterically.

Moving quickly, the guard drew a dagger from his belt and slid the blade under the piece of severed tongue that was still constricted around Wulfric’s wrist. With a hard jerk upward, he cut the tongue free, and it fell to the floor, still writhing like a fish flapping on a riverbank. Alfred stood ready with a skin of water, spilling it onto Wulfric’s wrist the moment the thing was removed. His flesh sizzled, wisps of smoke rising, and Wulfric saw a bright red welt encircling his wrist where the tongue had taken hold of him. The top layer of skin had been burned away by the beast’s saliva.

“It spits acid!” Alfred barked. “That is why we go no farther.”

Wulfric was still vaguely in shock. He took the water skin from Alfred and drank deeply. He looked back at the cell. The creature seemed to have calmed. It now lay slumped on its belly at the front of the cell, its head skewed sideways, and chewed lazily on the bars like a dog with a juicy bone. Wulfric watched as its wounded, bleeding tongue licked against the iron, covering it in its corrosive slobber.

“I ordered all the others destroyed,” Alfred explained. “This one, despite my reluctance, I kept. For who would believe the story on words alone?”

“What in God’s name is it?” Wulfric asked, still breathless.

“There is one thing of which I am certain,” said Alfred grimly. “Whatever it is, it was not created in God’s name.”