Читать книгу Abomination - Gary Whitta - Страница 14

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

SIX

ОглавлениеWulfric sat cross-legged in the center of a grassy meadow, idly considering a curious flower he had picked, a type he had not seen before and could not identify. It was a quiet moment, among the few he had known in many a month, save for sleep—and even that was, more often than not, a breeding ground for the nightmares that now plagued him. And so he tried to find some peace in each rare moment of quiet solitude, such as this one. Although, truth be told, having little else to occupy his mind only made it more difficult to ignore the pain from which he could find no relief.

Even now, months after that misshapen beast had attacked him in Alfred’s dungeon, Wulfric still bore the wound around his wrist—as fresh as though it had been inflicted yesterday. He had tried every salve and treatment he knew, but still he felt it burning under the bandage in which he kept it wrapped. At times it felt as though the beast’s tongue were there still, a phantom appendage encircling his wrist like a white-hot manacle, eating away at the layers of his flesh. Just another wretched aspect of Aethelred’s black magick—wounds that refused to be healed by medicine or even by time.

Wulfric was pulled from his reverie by the sound of footsteps in the soft grass behind him.

“The men are wondering if they are to sit here all morning, or if you plan on giving the order to attack,” said Edgard.

Wulfric glanced up at his fellow knight. Just as Wulfric was one of the few men in Alfred’s kingdom who had earned the right to speak to his King as an equal, Edgard was among the few who enjoyed a similar privilege with Wulfric. Every other soldier in England, even the most senior officers, addressed Wulfric with a degree of reverence that made any kind of useful or honest conversation impossible. But not Edgard, a knight who, like Wulfric, had once been a common man enlisted in Alfred’s army. He had fought alongside Wulfric in almost every battle against the Norse, before Ethandun and after.

They had liked each other instantly, from the first time they had broken bread around one of the enlisted men’s campfires. They were from the same county, they learned. Their families had bought fruit from the same local market and even knew a few of the same people. And both were men blessed—or cursed, perhaps—with an innate talent for battle. They had much in common and quickly became inseparable on the battlefield. Before long, the two of them had saved each other’s lives more times than either could remember. At first they had kept score in a running contest over bragging rights, but after a while, both men had lost count. Save Alfred himself, Wulfric knew of no man in all England he would more readily trust with his life. And so Edgard had been the first Wulfric had sought to enlist in his campaign to hunt down Aethelred and his army of the damned.

Edgard, unlike Wulfric, had not been so humble as to refuse the lavish lands and titles Alfred had gratefully offered them both after the war. But as it turned out, he had grown restless in his retirement. He was tired of his castle, expensive to maintain and impossible to heat, and even more tired of his wife, who nagged him incessantly. In truth, he had never much cared for her to begin with, but he had always wanted children more than anything, and she was the youngest of five sisters, the other four all having borne sons to their husbands.

Fate had decided that she would bear Edgard none, though not for the want of trying. When the arguments inevitably came, she never failed to remind him that she was of fertile stock, and so the fault must lie with him. Edgard had come to resent her, and his damned drafty castle, with all its empty bedchambers that should by rights be filled with the laughter of children. And so when Wulfric had come knocking on his door with an offer to fight by his side once more, Edgard asked no questions about the nature of the enemy or even the size of the reward; he simply seized the opportunity to ride away from all that reminded him of a life unfulfilled. Ending life comes to me much more easily than creating it, he had reflected sadly to Wulfric as they rode from his castle together.

Edgard had not looked back to see if his wife was watching him ride away. He had not even told her he was leaving.

Together they had wasted no time in marshaling the most potent small force of fighting men ever assembled. Nearly a hundred strong, they were handpicked veterans of the Danish campaigns, men Wulfric and Edgard knew could tip the balance in any engagement, and who would even the odds against Aethelred’s beasts. Alfred had tried to warn Wulfric that just one such beast was the equal of a dozen men. Not the men I plan to set against them, Wulfric had told himself.

Most of the men Wulfric and Edgard sought to recruit had at first laughed at the tale told them of Aethelred and his abominations. Some did not; they had heard stories in alehouses and around campfires of villages overrun by unspeakable shape-shifting horrors led by some dark warlock. But none hesitated to join; they would follow Wulfric and Edgard into battle against any enemy, no matter how improbable.

Their force assembled, Wulfric and Edgard had ridden northeast, tracking Aethelred’s own path toward the Danelaw border. Those among Wulfric’s men who had at first scoffed at his story became believers as they followed the trail of horrors the crazed archbishop had left in his wake. They had all seen settlements sacked by the Norse, but never anything like this. There were no bodies, no wounded. Instead, entire towns and villages had been emptied, leaving behind nothing but eerie desolation. As they surveyed the silent ruins of the first ghost town they encountered, Wulfric reminded his men of what the King had said of Aethelred. His enemies do not fall on the battlefield—they become his allies. Hardened men all, not one of them passed through that town without a shudder.

They had eventually caught up with Aethelred just outside Aylesbury, a small market town he had plundered for souls that very morning. It was not a moment too soon; Aylesbury was perilously close to the Danelaw border. And then there were no skeptics left among Wulfric’s men, for now they saw what lay before them with their own eyes: a great herd of nightmarish, oil-black beasts, their forms beyond imagination, slithering and lurching their way across the land as they howled and wailed, a hellish cacophony that in sound alone inspired revulsion and despair. And at their head, the lone figure of Aethelred, leading them onward like some demonic shepherd.

The creatures’ irregular shapes and movement made them difficult to number from a distance, but Wulfric had estimated the herd to be at least five hundred strong—the combined populations of the dozen or so villages and hamlets Aethelred had descended upon along his path now transformed into the grotesque horde lumbering along under his command.

Wulfric was a student of war, of battle tactics. He had thought long and hard during his pursuit of how best to confront Aethelred and his minions when he finally caught up with them, and had decided ultimately on the plan of attack that had always served him best—straight at the heart of the enemy, without fear or hesitation. Wulfric knew that Aethelred would be relying partly on the psychological fear his abominations struck into the hearts of all who laid eyes upon them. But Wulfric had neutralized that particular asset by selecting men he knew would not freeze or waver in the face of even the most terrifying enemy. Aethelred’s army is no different from any other we have faced and defeated countless times, he had reminded them the night before. A mindless horde of barbarians and animals without honor, or wits, or God on their side. He reminded them also that Cuthbert had been working tirelessly to bless the armor each of them wore with the protection that would render Aethelred’s other advantage useless in battle.

The speech had worked. In the morning, Wulfric and Edgard rode their force of a hundred men right at Aethelred, across an open field, their horses’ hooves thundering in the earth, swords drawn, unafraid, roaring bloody murder at the tops of their voices, so loud they rivaled the howls of Aethelred’s monstrous herd.

At first, Aethelred seemed to relish their approach. Standing defiant and unafraid before his army, he focused his attention on Wulfric and the tip of the oncoming spear. He raised his hands, bony fingers dancing through the air like a virtuoso harpist playing an unseen instrument as he recited an incantation. But his look of defiance slowly turned to one of consternation as Wulfric and his men kept coming, seemingly immune to the spell that should by now have contorted them into yet more broken and willing servants.

Cuthbert had done his job well. Wulfric’s armored breastplate shimmered with an iridescent glow as the protective seal the young cleric had placed upon it absorbed the brunt of Aethelred’s magick like a lightning rod and dissipated it harmlessly.

Aethelred cursed and began to prepare another incantation, but Wulfric’s army was by now just fifty yards away and closing quickly. And so Aethelred panicked and retreated into his horde, commanding them to attack as he did so. His monsters surged forward to meet Wulfric’s brigade. In the moments before they clashed, Aethelred found himself wondering why this small force of men, outnumbered by five to one and outmatched to a far greater degree, was not fleeing at the mere sight of his army, as so many had done before them. He could only assume that they were fools, or mad. But if he could not add them to his numbers, his beasts would surely make short work of them on the field.

Aethelred’s arrogant assumption was soon proved wrong. His army was a fearsome sight to be sure, but it had never before been tested in battle; any enemy encountered before now had either been turned or had fled in terror. This was his vile children’s first real taste of combat, and Aethelred discovered to his dismay that unlike Wulfric’s band of war-hardened veterans, they had no belly for it at all. In the initial chaotic throes, his monsters struck down several men, lashing out wildly with claw and fang and tentacle, but Wulfric’s cavalry hit back even harder, hacking and trampling a bloody swath through Aethelred’s mob, leaving abominations maimed and bleeding and shrieking in agony in their wake.

The shape of the battle changed rapidly after that, and Aethelred’s monstrous host collapsed into panic and disarray. To the surprise and delight of Wulfric and his men, it quickly became apparent that these hellish beasts were not so fearsome when confronted on equal terms—more akin to an unbroken horse, they spooked at the first sign of danger. Soon the entire horde was scattering and fleeing before Wulfric’s surging forces, even as Aethelred made a desperate attempt to maintain some semblance of discipline among them. Though Wulfric’s men were still engaged with several beasts that were doggedly fighting back—mostly those that had become enraged after being wounded—the archbishop could see that it was hopeless. With so many of his forces fled and his own magick rendered null, the battle was all but lost.

And so he sought instead to make his escape, marshaling a small group of his more obedient servants—those first few he had turned during his escape from Alfred’s tower. With them, he scurried away amidst the chaos, down an escarpment to the edge of a nearby forest, where he disappeared into the trees while Wulfric’s men finished off the rest of his beasts.

Wulfric lost twenty men that day—which was better than he had expected for having put well over a hundred beasts to the sword and scattering the rest to the winds. Now only Aethelred himself and whatever few abominations he still controlled remained a threat.

From then on, it became a hunting expedition. Wulfric and Edgard tracked the archbishop day and night, hoping to find him before he had the opportunity to replenish his numbers. The trail led them all the way to Canterbury, Aethelred’s seat, and to the cathedral where this whole horrific misadventure had first begun.

And now here they were, precisely four months from the day that Wulfric had ridden away from his wife and unborn child. It had been a long campaign, arduous for both body and spirit, but it was almost done, and he was almost home. His army was encamped not far outside Canterbury Cathedral. Aethelred was known to be inside, licking his wounds. One final battle to close the book on all of it, and Wulfric could at last return home. He would meet his son, by now a month old, for the first time, and make things right with Cwen. At last, he would begin his new life as a husband and father both.

But as anxious as he was to do all of that, he would not allow haste to be his undoing in these final hours. Aethelred had been bested in battle and his magick neutralized, but Wulfric knew better than to underestimate his opponent even now. He knew Aethelred to be a cunning man, a defiant man, and whatever he had been doing for the past three days holed up inside his cathedral, Wulfric felt sure that it was something more than simply waiting for him and his men to break down the door and finish him off.

No, Aethelred would not go down so easily as that. He surely had one final card still to play. The only question was, what?

Wulfric was still pondering that as Edgard looked at him, one eyebrow arched, waiting for an answer to his question. “That is why we’re here, isn’t it? To attack?”

Wulfric gazed across the plain at the spires of Canterbury, shrouded in morning mist. “We will attack when I have a better idea of what awaits us within, and not before,” said Wulfric.

“We know what awaits us within. Aethelred and at most a few dozen of his hellhounds—far fewer than we have already done away with. Why do we wait?”

They had kept a close watch on the path Aethelred had taken back to Canterbury as they followed, taking note of any settlements or towns he might have harvested for reinforcements. So far as they could discern, he had passed through none, opting instead for the most direct route back to Canterbury—meaning he could only have conscripted any individuals or small groups encountered along his way. Perhaps by now he had also turned Canterbury’s own staff and other retainers, but even then the numbers could add up to no more than Edgard was estimating. The sorcerer was trapped and under siege, his forces depleted, his magick useless. He was ripe for the finishing. Unless . . . The word ate away at Wulfric like the burning ring around his wrist.

“He’s been in there for days,” he observed with a nod toward the fog-shrouded cathedral in the distance. “Doing what, God only knows. Perhaps refining his magick to counter the wards on our armor. Perhaps training his remaining forces to better stand their ground, to fight more fiercely. Perhaps something we have failed to even consider. I don’t like it.”

“What evidence do you have to suggest any of this?” Edgard asked.

“None,” admitted Wulfric. “Only a bad feeling. Like the one I had before Chippenham. Remember that?”

“Hmph,” grunted Edgard, gazing out at the horizon. The two men had many differences on matters of war—from infantry strategies to the best way to silently cut a man’s throat—and had often debated late into the night, but Edgard had to admit that when it came to ill portents before a battle, Wulfric’s gut instinct was almost never wrong. He sighed.

“Wulfric, the only way for us to know what awaits us in there is to go and find it.”

Wulfric let the flower that confounded him fall from his fingers and stood, turning to look at his men, assembled not far behind him.

“Perhaps not,” he said. “Bring me Cuthbert.”

Edgard passed the order to a runner, and a few minutes later they saw the little cleric dashing across the field to where his commander stood, huffing as he ran, breath clouding in the morning mist. “It really is a wonder that boy’s still alive,” said Edgard with amusement as he observed Cuthbert’s awkward gait, his ill-fitting robes hanging off his willowy frame as though slung over a poorly made chair.

“That boy’s the reason any of us are still alive,” replied Wulfric. Cuthbert had come to earn his respect over the course of this campaign. High-strung and brittle he may have seemed at first blush, but when it mattered, he had proven himself no coward. At Aylesbury, Cuthbert had insisted on staying with the men until the last moment to ensure that every one of them had a freshly placed blessing on their armor, as well as on that of their mounts, before they entered the fray, in case the protective power of the spell—at that point, still an unknown quantity—should diminish over time. In doing so, he ventured far closer to Aethelred’s horde than he had thought himself capable. It was not until later, after the battle had ended, that he realized he had forgotten to place a protective blessing upon his own vestments and had left himself vulnerable to one of Aethelred’s curses. It was only by happenstance that he had not been targeted and turned into some dire beast that his own comrades would have been forced to put down. Cuthbert spent most of that night throwing up, but by then his actions on the field had earned him Wulfric’s esteem, and by extension the esteem of all the men.

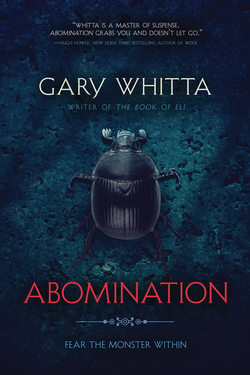

Cuthbert had also proven invaluable as a curator and archivist of the many and varied forms of misshapen wretch that Aethelred had taught himself to conjure. Many of the beasts had dispersed, in all directions, after the battle at Aylesbury, and they were now scattered far and wide throughout the kingdom, living and lurking in the shadows, masterless and wild. They had become the basis for a new folklore fast spreading throughout southern England: nightmarish stories told around campfires and to restless children about dark, malevolent, shapeless horrors that stalked their prey—animal and human alike—by night, taking whatever or whomever they could find and dragging their prey screaming into the darkness to be fed upon.

Wulfric’s men had encountered more than a few of these feral types during their pursuit of Aethelred after Aylesbury, and after each kill Cuthbert took pains to catalogue it in his own bestiary, kept carefully in a leather-bound volume. He made detailed drawings of each species they came across, taking note of its behavioral characteristics, speed, strength, intelligence, and preferred method of slaying, thus making the next confrontation with a beast of the same type that much swifter and less likely to result in casualties. Cuthbert’s work was as exhaustive and scholarly as it was useful in its practical application, and even Wulfric admitted to finding it darkly fascinating. It took him back to his boyhood, when his father would teach him to study and identify various forms of insect life. Now the insects were twice the size of a man and could kill you from twenty feet away, but the principle was the same.

Cuthbert arrived red faced and out of breath. He tried to speak but was too winded for words to come.

“Take a breath, boy!” barked Edgard. “A knee, if you must.”

Cuthbert took a moment to regain his composure and catch his breath. “I’m sorry. Sir Wulfric, you have need of me?”

“A few nights ago you told me of another spell in Aethelred’s scrolls that you had begun to translate before his escape,” said Wulfric.

It took a moment for Cuthbert to recall the conversation. “Oh! You mean the scrying?”

“Yes. Can it be done?”

Cuthbert hesitated. “I’m not sure. My translation was incomplete, and—”

“But what you did translate, you remember precisely.” By now, Wulfric had learned that Cuthbert’s claim of a flawless memory was not unfounded.

Cuthbert nodded.

“Excuse me,” Edgard interjected, “but what exactly are we talking about here?”

“From my understanding of the scrolls, scrying allows a person to see what is elsewhere,” said Cuthbert. “The spell describes the use of a reflective medium such as polished metal or a pool of still water to project the image of a distant location exactly as it appears at that moment, like a window into that faraway place. I have done my own study on this, and I believe it may be possible to go further, to actually cast an immaterial projection of oneself into that place, and to explore it remotely, just as though one were actually there.”

“And you can do this?” Wulfric asked, intrigued.

“In theory,” said Cuthbert. “But in matters of magick, it is often a far cry between theory and practice.”

“I need you to try,” said Wulfric. “I need to know what lies in wait within the cathedral before I commit my men. That knowledge could be the difference between victory and defeat, or at the very least determine how many of us survive the day. Do you understand?”

Cuthbert was silent as the weight of what Wulfric was asking began to sink in. He began to wonder what he might have just talked himself into. He felt his stomach start to ravel itself into a knot. “I understand,” he said finally, with as much calm as he could muster. “I will try.”